Abstract

Background

The recently published AJCC-TNM staging system for esophageal carcinoma made an obvious modification on N-classification based on the number of metastatic regional lymph nodes (LN). However, this classification might ignore the site at which these LNs occur, a factor that might be even more important in reflecting patients’ prognosis.

Methods

A retrospective study of 236 patients with carcinoma of thoracic esophagus who underwent esophagectomy between 1984 and 1989 with each at least six LNs removed was conducted, with a 10-year follow-up rate of 92.4%. The proposed scheme for N-classification according to the number (0, 1–2, 3–6, ≥7; N0–3), distance (0, 1, 2, 3 stations; S0–3), or extent (0, 1, and 2 fields; F0–2) of LN involvement was evaluated by univariate and multivariate survival analysis.

Results

The LN metastasis was identified in 112 patients, revealing a poorer 5-year survival in this patient group when compared to patients without node involvement. Cox regression analysis revealed that the number and distance of LN metastases and the number of metastasis fields were factors significantly influencing survival. When these factors were further analyzed by univariate log-rank test, no significant difference in survival existed between N2 and N3 patients, or among S1, S2, and S3 patients. When patients were grouped according to the extent of LN metastasis, significant differences in survival were observed overall and between each subgroup.

Conclusions

Refining the current N-classification for esophageal cancer according to the extent of LN metastasis, rather than by number alone, might be a better means of staging that could subgroup patients more effectively and result in different rates of survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor node metastasis (TNM) cancer staging system is widely used by clinicians to stratify patients with different prognosis and to select treatment strategies. With increased sophistication in cancer diagnosis and improvement in the understanding of biology, amendments to this system over time are advocated [1]. The T-category of the TNM staging system for esophageal cancer, among other forms of the disease, has been improved by using the depth of wall penetration instead of tumor length. However, N-classification, which reflects regional lymph node (LN) metastasis, remains imperfect [2]. LN status is a critical determinant of the prognosis and management of esophageal carcinoma. The most recent (7th) edition of the AJCC N-staging system for esophageal cancer groups patients as follows: N0 (those without LN metastasis), N1 (those with 1–2 positive nodes), N2 (those with 3–6 positive nodes), and N3 (those with ≥7 nodes) [3]. Increasing numbers of reports show that patients with different numbers of positive LN have differing survival experiences [1, 4–6]. It has also been discussion regarding subgrouping of patients according to the number and ratio of metastatic LN [7–13]. The purpose of the present study was to explore an optimal N-classification for esophageal cancer, by analyzing the clinicopathologic features and over 10 years of follow-up on patients with esophageal carcinoma treated by surgical resection.

Materials and methods

Patient population

From 1985 to 1989, a total of 236 patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) confirmed by endoscopy and biopsy underwent a cure-intent esophagectomy with at least six LNs dissected from each patient. There were 156 men and 80 women, ranging in age from 32 to 75 years (with an average age of 52.3 years). The tumors were located in the upper third of the esophagus in two patients, middle esophagus in 181 patients, and lower in 53 patients. The patients’ disease was staged according to the AJCC-TNM staging system for esophageal cancer, Seventh Edition [3]. Demographic data are summarized in Table 1. The frequency of resected LNs are shown in Table 2. The name and distance of LN metastasis were grouped according to Casson’s LN drainage map [14]. (Tables 3, 4). For 38 patients with only one LN metastasis, the skip metastasis was defined as follows: there was no continuous tumor cell spread from the primary tumor into the adjacent LN levels (station 1), but firstly appears in further one level (station 2) or more than one level (station 3) [15]. For 74 patients with multiple LN metastasis, 12 patients had metastases only in the thorax, 16 had metastases only in the abdomen, and 46 had metastases in both the thorax and the abdomen. The proposed scheme for N-classification was based on the number of affected LNs (N0 = 0; N1 = 1–2; N2 = 3–6; N3 ≥ 7), the distance from the primary tumor (S0 = 0; S1 = station 1; S2 = station 2; S3 = station 3), or the extent (F0 = 0; F1 = 1 field; F2 = 2 fields) of LN involvement.

Surgical procedure

All patients underwent an esophagectomy and lymphadenectomy via a left posterolateral thoracotomy. The number of LNs harvested per case ranged from 6 to 24 (mean 8.0).

Follow-up

All patients were followed by mail at 3-month interval for the first 2 years, at 6 months from year 3 to 5, and at 12-month intervals thereafter. The survival time was measured from the date of operation to the time of the last follow-up or death. “Lost to follow-up” was defined by a patient’s failure to respond to two consecutive mailed follow-up reminders.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The survival is depicted by Kaplan–Meier curves. The multivariate analysis was done by the Cox proportional hazard model. The log-rank test was used in the univariate analysis. The difference was considered statistically significant if P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS 12.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

There were no operative deaths in this series. Fourteen patients developed postoperative complications (5.9%), including three with anastomotic leakage, four with chylothorax, three with empyema, two with recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, and two with wound infection. The 10-year follow-up rate was 92.4%. Overall 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year survival rates were 80.2, 43.1, and 34.2%, respectively (Fig. 1). Among the 236 patients in the analysis, 112 had regional LN metastasis. The rate of LN metastasis was 47.5%. The 5-year survival rate of these patients was significantly lower than that for patients without LN metastasis (14.8 vs. 66.6%; P < 0.01). A total of 1,896 LNs were dissected; 337 were positive, with the degree of LN metastasis of 17.8%.

Possible prognostic factors were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. It revealed that besides the tumor location, the depth of invasion, and the differentiation grade of the primary tumor, the number of LN metastasis, the distance of LN metastasis, and the number of metastatic fields were all independent factors significantly influencing survival (Table 5).

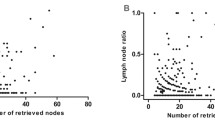

In order to investigate an optimal N-classification, the schemes of LN metastasis used in the multivariate analysis were further studied by univariate log-rank test. Although an overall significant difference in survival existed after univariate analysis according to the number of LN metastases, further analysis showed that the survival in N2 and N3 patients did not differ (Fig. 2). A similar result was observed when studying the distance of LN metastasis from the primary tumor; survival among S1, S2, and S3 patients was not significantly different (Fig. 3). In 38 patients who had a solitary LN metastasis, 29 of them (68.4%) were skip metastases, and there was no significant survival difference between patients with LN skip metastasis and solely adjacent LN involvement (Fig. 4). When comparing 74 patients with multiple LN metastases, patients with a single field LN metastasis (thorax versus abdomen) had a similar survival experience (Fig. 5). In contrast, if patients were grouped according to the extent of LN metastasis (F0, F1, F2), significantly different survival rates were observed overall and between the subgroups of patients (Fig. 6).

The extent of LN metastasis on the long-term survival for patients with esophageal carcinoma after operation (log-rank test, χ2 = 87.47; P < 0.01). There was a significant difference between each subgroup (F0 versus F1, χ2 = 42.15, P < 0.01; F1 versus F2, χ2 = 5.14, P = 0.02; F0 versus F2, χ2 = 83.30, P < 0.01)

Discussion

The AJCC cancer staging system is commonly used in unifying clinicopathological classification, guiding treatment decision making, evaluating prognosis, and comparing treatment results. LN metastasis is the most important independent prognostic factor affecting long-term survival in patients with esophageal cancer after curative resection [1, 16]. Thus, esophagectomy with LN dissection is a promising therapeutic strategy for esophageal cancer. Several reports have suggested that LN dissection improves surgical results [17, 18]. The current (Seventh Edition) of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual presents a vast improvement over previous editions for the N-staging of esophageal cancer by grouping patients according to different numbers of metastatic LN [3]. Several studies have evaluated the influence of the number of LN metastasis on the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer and have found significant differences in prognosis between the patients with different numbers or ratios of metastatic LNs [8, 9, 12, 13, 19]. However, there is not yet a well-accepted cut-off for the N-classification. Wilson et al. [13] reported that the prognosis of patients was worse with an increase in the number and extent of LN metastases. Mariette et al. [12] and other investigators have adopted a different cut-off of the number and ratio of the LN metastasis (Table 6). The present study first classified patients into four groups according to the number of LN metastases (N0 = 0; N1 = 1–2; N2 = 3–6; N3 ≥ 7). It revealed an overall significant difference in survival by univariate analysis. However, further analysis showed that survival in N2 and N3 patients did not differ.. Apparently it is difficult to establish an identical cut-off point for LN metastasis in each research center. This difficulty might be due to the different surgical procedures (2- or 3-field lymphadenectomy) used in each hospital, or the varing numbers of LN harvested from each patient. Moreover, the exact number of resected LNs is sometime difficult to count when what appears to be an enlarged metastatic LN is actually the coalescence of multiple positive LNs, or when a single enlarged LN becomes fragmented during dissection.

It has been reported that the distance of LN metastasis from the primary tumor influences prognosis [20]. The present study therefore investigated the N-classification according to LN metastatic station. There was no significant difference in survival identified among S1, S2, and S3 patients. The study went on to consider the influence on survival in patients with only one LN metastasis. There was no significant difference in survival between patients with a skip metastasis and those with a non-skip metastasis (P = 0.75). Because of the peculiarity of LN drainage in the esophagus, there is abundant lymphatic vessel communication in the esophageal submucosa, which not only transversally penetrates the esophageal wall and drains to the adjacent LNs but also has more longitudinal communication. This peculiarity of esophageal drainage forms the anatomic basis for the development of extensive skip metastases during the early phases of esophageal carcinoma [9, 21]. For this reason, the concept of the sentinel LN might not be applicable to esophageal carcinoma [15, 22]. Furthermore, it is considered to be improper to define N-classification of the esophageal carcinoma according to the distance of LN metastasis.

It has been reported that the number of fields with LN metastases provides a better index in evaluating the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer. The esophagus is a unique organ that passes through three main anatomic regions, the neck, chest, and abdomen. Logically, given the same number of positive LNs, the prognosis for various patients might differ if the positive LN clustered in one anatomic region (e.g., chest or abdomen) or if they were distributed to two or three regions. There was already evidence that use of the range (field) of LN metastasis was an easier and more precise way to subgroup ESCC patients according to different survival experience when An et al. performed a retrospective study on the clinical data of 217 patients who had undergone radical operation through three-field lymphadenectomy. They divided the 217 patients into four groups: no LN metastasis (group A), one field LN metastasis (group B), two fields LN metastasis (group C), and three fields LN metastasis (group D). They found that there was a significant difference in 5-year survival among the four groups. As the number of fields with LN metastasis increased, the 5-year survival decreased dramatically [21]. Shimada et al. also conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the prognostic impact of the extent and number of positive LNs on long-term survival in patients with esophageal carcinoma who underwent three-field lymphadenectomy. The 5-year survival rates of patients with different extent of LN metastasis were as follows: 69% for none, 50% for 1 field, 29% for 2 fields, and 11% for three fields of LN metastasis. They suggested that the extent of positive LNs should be considered an independent predictor of long-term survival [23]. The Tenth Edition of the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer categorizes LN metastasis according to both the number of metastatic fields and the number of metastatic LNs [24]. Our observation demonstrated that N-classification according to the number of field metastasis could stratify the patients with different prognosis. Moreover, the recognition of LNs in different anatomic regions (neck, thorax, or abdomen) was easier and obvious. It might be optimal for N-classification to be based on the number of fields with LN metastasis.

The main drawback of present study could be the limited number of LN harvested per case. Current criteria recommend taking as many LN as possible. LNs should be removed to provide a strong means for estimating N staging, but this use has to be balanced against the risk of complications. It is important to note, however, that the present study investigated patients who underwent operation 25 years ago. The goal was to have long-term follow-up data. At time of operation, no LN dissection criteria existed, and extensive lymphadenectomy was associated with a high morbidity and mortality rate. Nevertheless, when we investigated our datain light of the Sixth Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual criteria for esophageal carcinoma, which state that at least six nodes should be removed, the result was of significance. We have analyzed the effect of LN yield (LNY) on esophageal cancer staging in a previous study [25]. We demonstrated that if patients already had LN metastasis, the survival was similar between those patients with LNY < 6 and LNY ≥ 6. However, in “N0” patients, the survival was significantly better in those with LNY ≥ 6 when compared to those with LNY < 6, suggesting that the positive nodes might be missed more easily in patients with low LNY. Bogoevski et al. [10] also revealed that in patients with nodal involvement, no significant overall survival differences were identified when stratifying patients according to the LNY. Dutkowski et al. studied the proportional sensitivity of the LN status on up to 100 examined regional LNs and showed a sharp increase in N staging sensitivity when 0–6 LNs were removed. The sensitivity of a correct determination of pathological N classification (pN) already reached 83.9 ± 2.6% at six examined LNs. Proportional sensitivity then increased another 6% when up to 12 LNs were harvested, resulting in a sensitivity of 90 ± 2.2%; an additional but slight improvement could be observed when extending LN examination from 12 to 100 nodes [26].

The other limitation of the present study might be the operative route of left posterolateral thoracotomy. This procedure was widely used in China, especially in the northern high incidence areas since it had the advantages of fewer incisions, shorter operating time, and fewer complications. The disadvantage of this operative route was the incomplete lymphadenectomy [27]. The common hepatic nodes, celiac nodes, and upper right mediastinal nodes were difficult to remove, and the cervical nodes would be left intact. However, those regional LNs have been observed to be frequently involved by the primary lesions [28]. For those reasons, the present study was unable to negate the current number-based N-classification for esophageal carcinoma staging; nevertheless it did demonstrate a possible modification to define an easier and more practical schema to measure the degree of LN metastasis. Obviously, to obtain a robust conclusion, a multi-institutional collaborative study on a large data set with good quality would be needed.

In conclusion, N-classification of esophageal carcinoma according to the extent of LN metastasis might be better than by numbers alone, and it could provide a better basis for establishing subgroups of patients with different survival projections after esophagectomy. Further validation on a large data set is warranted, especially when defining the next AJCC esophageal cancer staging criteria.

References

Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rybicki LA et al (2003) Refining esophageal cancer staging. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 25:1103–1113

Dhar DK, Hattori S, Tonomoto Y et al (2007) Appraisal of a revised lymph node classification system for esophageal squamous cell cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 83:1265–1272

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC et al (2009) AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th edn. Springer, New York, pp 103–115

Rizk N, Venkatraman E, Park B et al (2006) The prognostic importance of the number of involved lymph nodes in esophageal cancer: implications for revisions of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 132:1374–1381

Hofstetter W, Correa AM, Bekele N et al (2000) 7) Proposed modification of nodal status in AJCC esophageal cancer staging system. Ann Thorac Surg 84:365–375

Altorki NK, Zhou XK, Stiles B et al (2008) Total number of resected lymph nodes predicts survival in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg 248:221–226

Hsu CP, Chen CY, Hsia JY et al (2001) Prediction of prognosis by the extent of lymph node involvement in squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 19:10–13

Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Nomura M et al (2005) Developing an appropriate staging system for esophageal carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 201:884–890

Fu JH, Huang WZ, Huang ZF et al (2007) The impact of different N1 status on the prognosis of the thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 23:28–30

Bogoevski D, Onken F, Koenig A et al (2008) Is it time for a new TNM classification in esophageal carcinoma? Ann Surg 247:633–641

Greenstein AJ, Litle VR, Swanson SJ et al (2008) Prognostic significance of the number of lymph node metastases in esophageal cancer. J Am Coll Surg 206:239–246

Mariette C, Piessen G, Briez N et al (2008) The number of metastatic lymph nodes and the ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes are independent prognostic factors in esophageal cancer regardless of neoadjuvant chemoradiation or lymphadenectomy extent. Ann Surg 247:365–371

Wilson M, Rosato EL, Chojnacki KA et al (2008) Prognostic significance of lymph node metastases and ratio in esophageal cancer. J Surg Res 146:11–15

Casson AG, Rusch VW, Ginsberg RJ et al (1994) Lymph node mapping of esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 58:1569–1570

Hosch SB, Stoecklein NH, Pichlmeier U et al (2001) Esophageal cancer: the mode of lymphatic tumor cell spread and its prognostic significance. J Clin Oncol 19:1970–1975

Zhang HL, Chen LQ, Liu RL et al (2010) The number of lymph node metastases influences survival and international union against cancer tumor-node-metastasis classification for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus 23:53–58

Fujita H, Kakegawa T, Yamana H et al (1995) Mortality and morbidity rates, postoperative course, quality of life, and prognosis after extended radical lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Comparison of three-field lymphadenectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg 222:654–662

DeMeester TR (1997) Esophageal carcinoma: current controversies. Semin Surg Oncol 13:217–233

Tachibana M, Yoshimura H, Kinugasa S et al (2001) Clinicopathologic factors correlated with number of metastatic lymph nodes in oesophageal cancer. Dig Liver Dis 33:534–538

Xu Y, Guo Z (2000) The number of lymph node with metastases influences survival in patients with cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 22:244–246 (Chinese)

An FS, Huang JQ, Chen SH (2003) Analysis of lymph node metastases of 217 cases of thoracic esophageal carcinoma and its impact on prognosis. Ai Zheng 22:974–977 (Chinese)

Fang WT, Chen WH (2008) Current trends in extended lymph node dissection for thoracic esophageal carcinoma: evidence and experience. China Oncol 18:345–349 (Chinese)

Shimada H, Okazumi S, Matsubara H et al (2006) Impact of the number and extent of positive lymph nodes in 200 patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after three-field lymph node dissection. World J Surg 30:1441–1449

Japanese Society for Esophageal Disease (2008) Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, 10th edn. Kanehara Co. Ltd, Tokyo

Hu Y, Hu C, Zhang H et al (2010) How does the number of resected lymph nodes influence TNM staging and prognosis for esophageal carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol 17:784–790

Dutkowski P, Hommel G, Bottger T et al (2002) How many lymph nodes are needed for an accurate pN classification in esophageal cancer? Evidence for a new threshold value. Hepatogastroenterology 49:176–180

Adachi W, Koike S, Nimura Y et al (1996) Clinicopathologic characteristics and postoperative outcome in Japanese and Chinese patients with thoracic esophageal cancer. World J Surg 20:332–336

Tachibana M, Kinugasa S, Yoshimura H et al (2005) Clinical outcomes of extended esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg 189:98–109

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to their participants, and they acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China under NSFC grant 30770982.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

This article was read at International Surgical Week ISW 2009 Adelaide, September 6–10, 2009 and the abstract was published in World J Surg (2009) 33:S1–S268. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0165-5.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, QR., Zhuge, XP., Zhang, HL. et al. The N-Classification for Esophageal Cancer Staging: Should it be Based on Number, Distance, or Extent of the Lymph Node Metastasis?. World J Surg 35, 1303–1310 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1015-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1015-9