Abstract

Background

Gallstones remain a common clinical problem requiring skilled operative and nonoperative management. The aim of the present population-based study was to investigate causes of gallstone-related mortality in Scotland.

Methods

Surgical deaths were peer reviewed between 1997 and 2006 through the Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality (SASM); data were analyzed for patients in whom the principal diagnosis on admission was gallstone disease.

Results

Gallstone disease was responsible for 790/43,271 (1.83%) of the surgical deaths recorded, with an overall mortality for cholecystectomy of 0.307% (176/57,352), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) of 0.313% (117/37,345), and cholecystostomy of 2.1% (12/578) across the decade. However, the majority of patients who died were elderly (47.6% ≥80 years or older) and were managed conservatively. Deaths following cholecystectomy usually followed emergency admission (76%) and were more likely to have been associated with postoperative medical complications (n = 189) than surgical complications (n = 36).

Discussion

Although cholecystectomy is a relatively safe procedure, patients who die as a result of gallstone disease tend to be elderly, to have been admitted as emergency cases, and to have had co-morbidities. Future combined medical and surgical perioperative management may reduce the mortality rate associated with gallstones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gallstone disease affects 15% of adult Western populations, 1–4% of whom will become symptomatic each year [1] and for whom cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice.

Although cholecystectomy has a relatively low operative mortality of 0.4–0.6% [2, 3], a higher 90-day population-based mortality of 0.74% has been reported in Scotland [4]. Postoperative mortality was associated with emergency admission, co-morbid cardiorespiratory disease, and advanced age [4]. In patients over 80 years undergoing cholecystectomy, a 3.6% mortality has been reported [5], accounting for 44.7% of all post-cholecystectomy deaths [3].

Patients considered unfit for cholecystectomy may be effectively treated with percutaneous cholecystostomy, a procedure that is particularly suitable for elderly patients with acute cholecystitis and co-morbidity [6]. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has been increasingly used as a therapeutic rather than a diagnostic modality [7] for the perioperative extraction of bile duct calculi and to perform a sphincterotomy or biliary tree drainage as a definitive treatment in patients who are not fit for other operative interventions. However, ERCP itself can result in significant morbidity and mortality. A recent systematic survey of 21 prospective studies suggested a complication rate attributable to ERCP of 6.85% and a mortality rate of 0.33% [8].

Despite an extensive literature and multiple modalities for potential intervention, patients with gallstones continue to die under surgical care [2–5]. Using third party peer review of surgical deaths conducted for the Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality (SASM) (www.sasm.org) [9, 10], the present population-based study examined deaths reported to SASM between the years 1997 and 2006 to gain a contemporary insight into gallstone-related mortality and to determine the potential to improve care in patients with gallstones.

Methods

The Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality (www.sasm.org) [9, 10] examines all deaths in Scotland (population 5 million) that have occurred in National Health Service or independent sector hospitals while the patient was under surgical care. Data collection forms are sent to the consultant surgeon responsible for the patient during the final hospital episode and to the anesthetist if applicable. The returned forms are then anonymously reviewed by consultant surgical and anesthetic assessors who identify any adverse events in management and may request a confidential case note review if there is sufficient concern. This detailed second assessment occurs in approximately 10% of cases and is performed by a second-line assessor with a special interest in the relevant field. Adverse events are identified and fed back to the surgeon and anesthetist who cared for the patient. Since 2001 SASM has also recorded details of postoperative complications in those patients who die.

For the purposes of the present study the SASM database was analyzed for details of any patient who had died in a Scottish hospital between 1997 and 2006 where the principal diagnosis on admission was gallstone disease. Basic demographic data were sought on all patients, and additional information was obtained on those patients who were managed with cholecystectomy, ERCP, or cholecystostomy. Supplementary population data were obtained from the Information Services Division, NHS Scotland. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The chi square test was used for nonparametric analysis. A P value of less 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Gallstone disease was the main diagnosis on admission in 790 (1.83%) of the 43,271 patients who died under surgical care over the 10-year period 1997–2006. Of those, 376 patients (47.6%) were 80 years of age or older, and many were considered unfit for interventional procedures; more detailed information was available only on those patients who had undergone operative or procedural treatment.

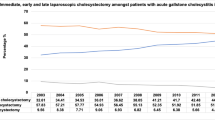

During this 10-year period 176 patients died after cholecystectomy. Forty-two patients (24%) died following elective cholecystectomy. From data in the Information Services Division of NHS Scotland, it was determined that 45,045 elective procedures had been performed during this period (0.093% mortality). One hundred and thirty-four patients (76%) admitted on an emergency basis underwent cholecystectomy during their final surgical stay (1.09% of the 12,307 emergency cholecystectomies recorded). Thus, the overall mortality for cholecystectomy in Scotland across the decade was 0.307%. Over the 10-year period there was no significant change in the annual mortality rate for elective cholecystectomy (χ2 = 10.0; P = 0.35). However, the annual mortality rate for emergency cholecystectomy decreased (χ2 = 23.54; P = 0.005). This is exemplified by data from the beginning and end of the study period. In 1997, 11 of 875 patients treated by emergency cholecystectomy died (1.3%), but in 2006 only 10 of 1,820 emergency cholecystectomy patients died (0.55%).

Patients who died post-cholecystectomy had a median age of 75 years (range: 39–103 years) (Fig. 1) and many had co-morbidity: 112 (64%) had pre-existing cardiovascular disease; 63 (36%) had respiratory disease, and 27 (15%) had renal disease. Four patients who died post-cholecystectomy also underwent ERCP. Surgical peer review identified 115 adverse events and anesthesia review revealed 72 adverse events (Table 1) with failures of process (delays in diagnosis, transfer, or operation; failure to use enhanced care facilities) rather than technical errors (criticism of surgical approach or endoscopic perforation) more frequently highlighted. A consultant surgeon performed or directly supervised cholecystectomy in 111 (63%) patients, but the surgeon was considered too junior for only 6 of the patients who died.

A total of 104 post-cholecystectomy deaths occurred after 2001, and details of postoperative complications were recorded for all of these patients. Postoperative medical complications (n = 189) such as cardiac failure, pneumonia, or renal failure were more common than surgical complications (n = 36) such as bleeding or sepsis. Cardiovascular (n = 75, 40%), respiratory (n = 74, 40%), and renal (n = 25, 13%) events were the most frequent medical complications. Sepsis (n = 11, 31%) and bleeding (n = 7, 19%) were the commonest surgical complications.

During the same 10-year period 117 patients with gallstones died under surgical care after ERCP had been their major treatment modality. During this timeframe 37,345 ERCPs had been performed for the treatment or diagnosis of gallstone disease, a mortality rate of 0.313%. The median age of these patients was 79 years (range: 53–96 years) (Fig. 1). Ninety-eight patients (84%) were admitted on an emergency basis, and 17 (15%) were admitted electively (data not recorded for 2 patients). Three patients primarily managed by ERCP subsequently underwent percutaneous drainage of the gallbladder prior to death.

As for cholecystectomy, many patients who died after ERCP also had significant co-morbidities. Sixty-one (52%) had recorded cardiovascular disease, 33 (28%) had respiratory disease, and 33 (28%) had renal disease.

Eighty-one of the post-ERCP deaths occurred after 2001, and details of post-procedure complications included cardiovascular (n = 40; 34%), respiratory (n = 33; 28%), and renal (n = 21; 18%) events. Technical complications included endoscopic perforation (n = 7; 6%), procedure-related sepsis (n = 3; 3%), and bleeding (n = 2; 2%) among the 35 adverse events identified by surgical peer reviewers (Table 1).

Only 12 patients, median age of 82.5 years (range: 59–92 years), were identified over the decade who died after percutaneous cholecystostomy alone. A total of 578 patients had undergone cholecystostomy during this time, suggesting a mortality for cholecystostomy of 2.1%. Ten medical complications were observed in these patients, compared with one technique-related complication of procedure-related sepsis.

Discussion

Although morbidity and mortality following major gastrointestinal [11–14], vascular [15, 16], or cardiac [17] surgery have received considerable publicity, the risks of gallstone disease, a common pathology in every surgical hospital, have received much less attention. Cholecystectomy is likely to be performed from a surgical ward base; ERCP and cholecystostomy may be performed by interventional physicians from nonsurgical wards where mortality audit is not part of standard practice. Thus, the mortality for ERCP and cholecystostomy presented here may be an underestimate.

However, this population-based study has demonstrated that elective cholecystectomy is a relatively safe procedure with a mortality of 0.09%, less than over a decade ago [4]. Because laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been widely practised in Scotland since the early 1990s [18, 19], it is likely that most patients underwent elective cholecystectomy at least initially attempted by a laparoscopic approach. Although the mortality after emergency admission and subsequent cholecystectomy is factorially higher (1.1%), this number is comparable with other European experience [20]. In the emergency setting, surgical and anesthetic assessors identified delay to surgery as an area of concern (Table 1). The limited enthusiasm for acute cholecystectomy [20–22] may reflect the historic strategy of conservative management during the index admission with subsequent elective cholecystectomy, although such delay significantly increases the conversion rate when laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed for acute cholecystitis [23]. Delays may be compounded by the increasing tendency to hand on patients from one on-call team to another as the surgical team structure becomes increasingly fragmented, an issue increasingly occurring in the UK.

While consultant surgeon involvement in 63% of operations suggests room for increased senior surgical input, surgical assessors considered that the lead surgeon was too junior in only 6 cases (3.4%). In only 4 deaths was the seniority of the anaesthetist considered an adverse factor. Thus, while elderly emergency patients with attendant co-morbidities undergoing surgery for gallstone disease should merit the most senior surgical and anesthetic intervention, in practical terms, the seniority of staff was rarely a factor in gallstone-related mortality.

Elderly patients with co-morbidities admitted as an emergency may be considered more optimally managed by endoscopic or percutaneous drainage. The small number of deaths following cholecystostomy may be regarded as supportive of the technical and clinical success that can be achieved with cholecystostomy in the elderly, co-morbid population despite the lack of randomized trials to fully evaluate this technique [6]. Other research has shown that the longer term results of this approach are acceptable [24].

The Scottish mortality rate of 0.313% after ERCP is similar to the prospective multicenter report of Andriulli et al. (mortality rate of 0.33%) [8]. The SASM data show that the majority of the patients who died following endoscopic treatment of gallstones did not undergo concomitant cholecystectomy. This may be expected given the preponderance of elderly co-morbid individuals in this cohort of patients and the prevailing view that cholecystectomy may not be necessary in elderly individuals who undergo endoscopic treatment of ductal calculi due to limited life expectancy and the relatively low rate of recurrent biliary events [25, 26]. Schreurs et al. reported on 164 patients (median age of 78 years) who underwent endoscopic clearance of common bile duct stones (±sphincterotomy) but had their gallbladder left in situ; 26% of those patients died of unrelated causes during a median follow-up of 74 months[25]. However, 16% of patients re-presented with symptomatic biliary disease (compared with 7.6% of younger, fitter patients who were managed with ERCP and cholecystectomy) [25]. Similarly, individuals over 65 years of age with choledocholithiasis treated by ERCP and sphincterotomy had recurrent biliary events in 2% of patients per annum [26].

A recent systematic review has suggested that all patients with common bile duct stones who are “considered fit for surgery” should proceed to cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy as this reduces mortality and morbidity [27]. However, that review acknowledges that further clinical trials are necessary as there is a paucity of data relating to “high risk” patients and it seems likely that many of the SASM patients would fall into this category or be “considered not fit for surgery.”

The process-related adverse events and potential for enhanced medical management suggest that mortality from gallstone disease could be reduced in future through timely intervention and enhanced perioperative management of cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal disease. The latter has been a focus of sustained effort in orthopedic circles with a reduction in mortality in hospital after orthopedic admission recorded in recent years by SASM (www.sasm.org). Such an approach of optimization has been successful in cardiovascular circles [28] and is in clinical trials for more general surgical procedures [29].

In conclusion, gallstone disease is an infrequent cause of death in contemporary surgical practice with cholecystectomy, ERCP, or cholecystostomy—all relatively safe procedures used to ameliorate the effects of gallstones. However, emergency presentation in elderly patients with co-morbidities remains a challenge for determining the optimum intervention(s) and the treatment roles of surgery, ERCP, percutaneous drainage, or conservative management. The majority of patients who died following cholecystectomy developed medical rather than surgical complications, including delays in process rather than technical adverse events. This finding suggests that enhanced medical management of these patients and attention to the patient pathway may be necessary to reduce mortality from gallstones (Table 1).

References

Gurusamy KS, Samraj K, Fusai G et al (2008) Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD007196

Nilsson E, Fored CM, Granath F et al (2005) Cholecystectomy in Sweden 1987–99: a nationwide study of mortality and preoperative admissions. Scand J Gastroenterol 40:1478–1485

Rosenmuller M, Haapamaki MM, Nordin P et al (2007) Cholecystectomy in Sweden 2000–2003: a nationwide study on procedures, patient characteristics, and mortality. BMC Gastroenterol 7:35–43

McMahon AJ, Fischbacher CM, Frame SH et al (2000) Impact of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a population-based study. Lancet 356:1632–1637

Maxwell JG, Tyler BA, Rutledge R et al (1998) Cholecystectomy in patients aged 80 and older. Am J Surg 176:627–631

Winbladh A, Gullstrand P, Svanvik J et al (2009) Systematic review of cholecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford) 11:183–193

Knudson K, Raeburn CD, McIntyre RC Jr et al (2008) Management of duodenal and pancreaticobiliary perforations associated with periampullary endoscopic procedures. Am J Surg 196:975–981

Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G et al (2007) Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol 102:1781–1788

Stonebridge PA, Thompson AM, Nixon SJ (1999) Completion of the journey of care: Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality (SASM). J R Coll Surg Edinb 44:185–186

Thompson AM, Stonebridge PA (2005) Building a framework for trust: critical event analysis of deaths in surgical care. Br Med J 330:1139–1142

Parks RW, Bettschart V, Frame S et al (2004) Benefits of specialisation in the management of pancreatic cancer: results of a Scottish population-based study. Br J Cancer 91:459–465

Tekkis PP, Poloniecki JD, Thompson MR et al (2003) Operative mortality in colorectal cancer: prospective national study. Br Med J 327:1196–1201

McCulloch P, Ward J, Tekkis PP (2003) Mortality and morbidity in gastro-oesophageal cancer surgery: initial results of ASCOT multicentre prospective cohort study. Br Med J 327:1192–1197

Thompson AM, Ashraf Z, Burton H et al (2005) Mapping changes in surgical mortality over 9 years by peer review audit. Br J Surg 92:1449–1452

Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Fourth National Vascular Database Report 2004

National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Death (2005) Annual Report. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: a service in need of surgery?

Keogh B, Spiegelhalter D, Bailey A et al (2004) The legacy of Bristol: public disclosure of individual surgeons’ results. Br Med J 329:450–454

Lam CM, Murray FE, Cuschieri A (1996) Increased cholecystectomy rate after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Scotland. Gut 38:282–284

Campbell EJ, Montgomery DA, Mackay CJ (2008) A national survey of current surgical treatment of acute gallstone disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 18:242–247

David GG, Al-Sarira AA, Willmott S et al (2008) Management of acute gallbladder disease in England. Br J Surg 95:472–476

Cameron IC, Chadwick C, Phillips J et al (2004) Management of acute cholecystitis in UK hospitals: time for a change. Postgrad Med J 80:292–294

Cameron IC, Chadwick C, Phillips J et al (2000) Current practice in the management of acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 87:362–373

Hadad SM, Vaidya JS, Baker L et al (2007) Delay from symptom onset increases the conversion rate in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. World J Surg 31:1201–1298

Griniatsos J, Petrou A, Pappas P et al (2008) Percutaneous cholecystostomy without interval cholecystectomy as definitive treatment of acute cholecystitis in elderly and critically ill patients. South Med J 101:586–590

Schreurs WH, Vles WJ, Stuifbergen WH et al (2004) Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones leaving the gallbladder in situ. A cohort study with long-term follow-up. Dig Surg 21:60–64

Boytchev I, Pelletier G, Prat F et al (2000) Late biliary complications after endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones in patients older than 65 years of age with gallbladder in situ. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 24:995–1000

McAlister VC, Davenport E, Renouf E (2007) Cholecystectomy deferral in patients with endoscopic sphincterotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD006233

Dawson J, Vig S, Choke E et al (2007) Medical optimisation can reduce morbidity and mortality associated with elective aortic aneurysm repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 33:100–104

Cuthbertson BH, Campbell M, Stott SA et al (2010) A pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of fluid loading and level of dependency in high-risk surgical patients undergoing major elective surgery: trial protocol. Trials 11:41 (Epub ahead of print, Apr 16, 2010)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dave Stobie, David Readhead, Christine Torrance, and Lynsey Kerr from the Information Services Division of the National Health Service (NHS), National Services Scotland, for assistance with this research. They also acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Jamie Young, Department of Surgery, Ninewells Hospital, for help with statistical analysis.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scollay, J.M., Mullen, R., McPhillips, G. et al. Mortality Associated with the Treatment of Gallstone Disease: A 10-Year Contemporary National Experience. World J Surg 35, 643–647 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0908-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0908-3