Abstract

Background

In cases of gastroparesis where significant symptoms fail to respond to standard medical therapy, gastric electrical stimulation (GES) may be of benefit. Unfortunately, not all patients improve with this therapy. Reliable preoperative predictors of symptomatic response to GES may allow clinicians to offer this expensive and invasive treatment to only those patients most likely to benefit.

Methods

Therapy was initiated in 15 patients more than 12 months prior to this retrospective review of our prospectively maintained data. All patients completed a Total Symptom Score (TSS) survey at every encounter as well as the SF-36 quality-of-life instrument prior to surgery. A failure of GES therapy was considered to have occurred when after 1 year of treatment, preoperative TSS had not decreased by at least 20%.

Results

Four patients (4 idiopathic) failed to improve more than 20% on multiple assessments after a year of therapy. All diabetic patients experienced a durable symptomatic improvement with GES. Review of individual items of the TSS revealed that nonresponders experienced less severe vomiting preoperatively.

Conclusions

Diabetic gastroparesis patients respond best to GES. Responders tend to have more severe vomiting preoperatively. Patients with idiopathic gastroparesis who do not experience severe vomiting should be cautioned about a potentially higher rate of poor response to GES and may be better served with alternative treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastroparesis is a chronic condition characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, and epigastric pain are common [1]. Patients with severe gastroparesis are often debilitated with a poor quality of life. Pain, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, and/or malnutrition can lead to frequent emergency department visits and hospital admissions. The most common etiologies of gastroparesis include diabetes, gastric surgery with vagus nerve injury, and idiopathic gastroparesis. Idiopathic gastroparesis is a poorly understood condition that most often strikes young females. Although the exact mechanism of idiopathic gastroparesis is not defined, postulated theories include damage to the gastric myenteric plexus as a result of a viral illness and/or myenteric hypoganglionosis resulting in a decreased number of interstitial cells of Cajal [2, 3]. Other less common causes of gastroparesis include medications, Parkinson’s disease, collagen vascular disorders, thyroid dysfunction, liver disease, chronic renal insufficiency, and intestinal pseudo-obstruction [4].

The medical treatment of gastroparesis includes dietary modifications (small, frequent, low-fat and low-fiber meals) as well as antiemetic and prokinetic medical therapy [5]. Unfortunately, medical therapy is associated with variable response rates and a high rate of intolerable side effects [2]. Some patients with severe gastroparesis may require surgical therapy for enteral access (jejunostomy tube) and symptom control (pyloroplasty or gastrectomy). Unfortunately, surgical treatments of medically refractory gastroparesis symptoms have historically been plagued with high morbidity rates without consistent gastroparesis symptom response rates [5].

Gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is a contemporary treatment option for the symptoms of medically refractory gastroparesis symptoms. GES has been demonstrated to be of benefit for patients with severe and medically refractory gastroparesis [6]. GES involves the surgical implantation of unipolar electrodes into the muscular layer of the gastric antrum that deliver high-frequency, low-energy pulses of electrical energy. Unfortunately, not all patients with severe symptoms from medically refractory gastroparesis respond adequately to GES. We sought to determine if easily derived patient factors can accurately identify patients most likely to respond to GES therapy.

Materials and methods

From October 2005 to December 2007, GES systems were implanted into 25 patients with medially refractory gastroparesis at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics. Indications included diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Therapy was initiated in 19 patients more than 12 months prior to this retrospective review of prospectively maintained data. Three patients were lost to follow-up and one patient died from unrelated causes 4 months postoperatively. The remaining 15 patients made up the study group. All patients had documented delayed gastric emptying on a nuclear medicine gastric emptying study. For the gastric emptying studies, patients consumed a scrambled egg meal labeled with 0.5 mCi of Tc-99 m sulfur colloid. Anterior planar images were obtained for 2 h by nuclear camera imaging and time/activity curves were generated. Mechanical obstruction was ruled out with an upper endoscopy or upper GI study radiograph series. All patients had tried and failed conservative measures (gastroparesis diet and prokinetic medical therapy) for at least 6 months prior to being considered for GES therapy.

Implantation of GES systems (Enterra Therapy, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) was completed either laparoscopically or robotically by a single surgeon (JG). The procedure has been described in detail previously [6, 7]. Clinical follow-up after the initiation of GES therapy was at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 6 months, and every 12 months after surgery per our protocol. In addition, if symptoms have not improved patients are seen every 4-6 weeks to have adjustments made to the GES treatment parameters. A single nurse practitioner (GB) was responsible for all of the postoperative visits and stimulator adjustments. All patients were administered a gastroparesis Total Symptom Score (TSS) survey at every visit. The TSS is a six-item survey in which common gastroparesis symptoms (vomiting severity, nausea, early satiety, bloating, after-meal fullness, and epigastric abdominal pain) over the preceding 2 weeks are rated on a 5-point Likert scale: 0 = no symptoms, 1 = mild (not influencing usual activity), 2 = moderate (diverting from but no modifications of usual activity), 3 = severe (influencing usual activity, requiring modifications), and 4 = extremely severe (requiring bed rest). The sum of the severity ratings of the six items are then totaled for the overall TSS. The TSS instrument has been used to evaluate efficacy in numerous GES series, including the clinical trial that led to the FDA approval for this particular device [2]. Although the TSS itself has not undergone a rigorous evaluation and validation process, five of the six items are similar to items included in the nine-question Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI). The GCSI has been demonstrated in studies to be a reliable and valid instrument for measuring the symptom severity in gastroparesis [8]. A failure of GES therapy to produce clinically meaningful benefit was deemed to have occurred if after 1 year of treatment, TSS had not decreased by 20% when compared to preoperative values on multiple assessments. This cutoff was selected based on previously published research [9].

In addition to the TSS survey, all patients completed the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) to quantify overall quality of life and health. The SF-36 is a validated and reliable survey that quantifies quality of life based on eight domains: vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, role physical, role emotional, role mental, and mental health. The results of each individual item are then translated to another scale from 0 (worst) to 100 (best), with the U.S. norm being 50 ± 10. The Mental Component Summary (MCS) and Physical Component Summary (PCS) are summary scales for each of these eight domains. Because each component scale measures hundreds of levels of health and extends the range of measurement to higher and/or lower levels than the eight subscales, individuals rarely score at the very top or very bottom of the PCS or MCS scale, making these scales useful for evaluating a general effect of an intervention across subscales. Data were collected prospectively and retrospectively reviewed. Preoperative TSS scores were compared to all postoperative values using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Preoperative SF-36 composite scale scores (MCS and PCS) were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board.

Results

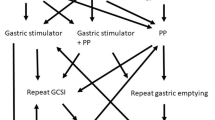

There were nine patients with diabetic and six with idiopathic gastroparesis who met inclusion criteria for this study. Two patients (1 diabetic and 1 idiopathic) were nutritionally compromised and unable to eat to the point where jejunostomy tubes were placed concurrently at the time of surgery to initiate GES. Both of these tubes were removed at 6 and 8 weeks postoperatively once oral nutritional intake improved to acceptable levels. Of the 15 patients treated with GES for more than 12 months, 11 had greater than 20% improvement in symptoms (responders) compared to 4 patients who did not (nonresponders). Table 1 gives the patient characteristics of both responders and nonresponders. Although gender was not a statistically significant variable that differed between study groups, all male subjects were responders to GES therapy. In addition, subjects who responded tended to suffer from gastroparesis symptoms for a longer period of time prior to the initiation of GES, although again this did not reach statistical significance. TSS scores prior to surgery did not differ for those patients who would eventually respond to GES compared to those who would not (Table 2). After 1 year of therapy, responders’ mean TSS score had decreased to 7.9 (from 17.3, p < 0.01) while nonresponders’ mean TSS was 14.8 (from 16.5, p = 0.3). Preoperative scores for individual symptoms assessed in the items of the TSS are depicted in Fig. 1. Nonresponders experienced significantly less severe vomiting preoperatively. All other symptoms were present in both groups with the same frequency prior to the initiation of GES therapy. Figure 2 illustrates mean postoperative TSS symptoms components, identifying the degree of response that subjects had for each category. Responders had significant improvement in early satiety and epigastric pain compared to nonresponders. When evaluating specific etiologies and symptoms, no patient with idiopathic gastroparesis (IG) and mild or no vomiting responded to GES after more than a year of therapy (3/3).

Responders had a significantly higher preoperative MCS scores compared to nonresponders (Table 2). With regard to preoperative gastric emptying studies, comparisons were difficult to make because three patients (all responders) had 0% gastric emptying at 120 min and T1/2 times could not be calculated. Average calculated gastric emptying T1/2 for the four nonresponders was 289 ± 25 min (range = 253–311 min). For the patients who responded to GES (excluding the 3 patients with 0% emptying at 2 h), mean T1/2 was 385 ± 283 min (range = 169–911 min; p = 0.6). Calculated gastric emptying T1/2 normalized in 0 nonresponders and in 7 of 11 responders (including 1 patient with 0% emptying at 2 h preoperatively) at the 6-month follow-up gastric emptying assessment.

Discussion

Gastroparesis is a disease that may result in symptoms that can be difficult to treat. In many patients, medical therapy is poorly tolerated and ineffective. GES is a promising therapy that can be of benefit for many patients with refractory and severe gastroparesis symptoms. Unfortunately, not all patients with gastroparesis and symptoms ultimately derive benefit from GES and currently there is no noninvasive test that can predict whether a patient is likely to ultimately respond. Temporary GES has been employed as a means of evaluating potential patients for permanent GES system implantation. Good correlation between early response to temporary GES and permanent GES has been observed [10]. The primary drawback to temporary GES is that it requires either a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube or endoscopically placed wires that exit the patient’s mouth for the duration of the trial period. Temporary endoscopic GES is also fraught with frequent electrode dislodgement and the need for repeated endoscopic lead placement in some patients. The ability to predict the potential for response (or lack thereof) to GES with easily attainable data is of obvious benefit to prospective patients.

In the current study we observed that patients with diabetic gastroparesis responded most consistently to GES and that there was a tendency for nonresponders to be female and to have suffered from gastroparesis symptoms for a longer period of time prior to initiating therapy. These differences in the duration of symptoms and gender were not statistically significant. In general, diabetic patients tend to suffer from a more progressive onset of gastroparesis symptoms and most idiopathic gastroparesis patients are female. We believe that gender and duration of symptoms may be dependant variables predictive of response and related to the gastroparesis etiology for an individual patient. Other published series that used the TSS to measure symptomatic outcomes of GES objectively have demonstrated similar response rates, especially in diabetics [9, 11].

Patients with vomiting as a major preoperative symptom were also observed to exhibit a high response rate. Perhaps just as valuable was the insight that patients with idiopathic gastroparesis and minimal to no vomiting prior to GES had extremely low response rates (0/3 responded). These findings are similar to those of other groups that examined this issue. Maranki et al. [12] implanted GES systems in 28 patients and observed that after a mean follow-up of 148 days, clinical parameters associated with a favorable clinical response were diabetic rather than idiopathic gastroparesis, nausea/vomiting rather than abdominal pain as the primary symptom, and independence from narcotic analgesics prior to GES implantation. It has been suggested that conclusions regarding the efficacy of GES before 1 year may be premature because it can sometimes take this long for certain patients to respond [13]. Despite this fact, all responders in the current study had demonstrated a greater than 20% decrease in TSS by 3 months postop.

An interesting finding of the current study is the association between the generic quality-of-life instrument (SF-36) component summary scores and symptomatic outcomes with GES. Velanovich [14] found that GES resulted in statistically significant improvement in the health transition item and social functioning domain of the SF-36. Lin et al. [11] discovered that both the PCS and the MCS score for 48 diabetic patients who underwent GES therapy were improved after 6 months and sustained at 12 months postop. We believe that ours is the first study to evaluate generic quality-of-life composite scores as a predictor of clinical response to GES. It is possible that mental health factors may play a significant role in a patient’s perception of both gastroparesis symptoms and in the symptomatic response to GES. Further studies in this area are needed to determine if treatment success may be increased by focusing on preoperative psychological counseling and coping strategies. An alternative view is that perhaps patients with certain mental health factors are less likely to respond to GES and different therapies should be pursued in these cases. Soykan et al. [15] have demonstrated that patients with elevated gastrointestinal psychosomatic susceptibility (as measured by the Millon Behavioral Health Inventory) respond poorly to prokinetic medical therapy. This provides further support to the theory that psychological factors may play a role in the response of gastroparesis symptoms to therapy. Psychological screening and counseling may ultimately prove to have value both in patient selection and in terms of maximizing therapeutic benefit of GES.

The exact mechanism of action of GES is unknown but various theories have been postulated, including altered autonomic nervous system tone, altered enteric nervous system function, reduced gastric sensitivity to gastric distention, and enhanced fundal relaxation [16]. A direct central nervous system effect may involve the stimulation of a central nausea and vomiting center in the brain leading to symptomatic improvement. A study of patients with GES for 1 year examined the physiologic effects of therapy. Using electrocardiogram, gastric barostat measurement, and positron emission tomography brain imaging, investigators determined that a significant increase in vagal and thalamic activity occurred. In addition, a significant increase in the discomfort threshold for both pressure and volume with gastric distention was demonstrated. This study suggests that symptomatic improvement following GES may be due to enhanced vagal autonomic function, decreased gastric sensitivity to distention, and the activation of central control mechanisms for nausea and vomiting through thalamic pathways [17]. This may help to explain why patients with more severe and frequent vomiting seem to respond to GES better than those with little vomiting.

Our study has several limitations. This is a nonrandomized retrospective review of a case series. Our sample size is small and outcomes are assessed subjectively. Our decision to require that patients demonstrate a more than 20% decrease in baseline TSS to be considered a responder to therapy is somewhat arbitrary but is based on a previously published 3-year follow-up on 55 GES patients [9]. We believe that the key to consistent positive symptomatic outcomes with GES is appropriate patient selection. In our opinion, these data suggest that idiopathic gastroparesis patients without vomiting as a symptom have a low likelihood of symptomatic relief with GES. We advise these patients of our opinion that symptom response rates are low in such circumstances and recommend that they pursue alternative treatment. We temper this advice with the knowledge that our clinical series is small and treatment patterns should not be defined by four patients.

It is possible to identify preoperatively a subset of medically refractory and symptomatic gastroparesis patients who are less likely to respond to GES. Patients whose gastroparesis is secondary to diabetes and those who suffer from significant vomiting are most likely to experience the subjective relief of symptoms. Patients with idiopathic gastroparesis and without vomiting should be cautioned about a potentially higher GES treatment failure rate and alternative therapies should be considered. Further follow-up and perhaps additional indicators will be necessary to increase the preoperative ability to predict response to GES.

References

Hasler WL (2008) Gastroparesis—current concepts and considerations. Medscape J Med 10(1):16

Abell T, McCallum R, Hocking M et al (2003) Gastric electrical stimulation for medically refractory gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 125:421–428

Monnikes H, van der Voort I (2006) Gastric electrical stimulation in gastroparesis: where do we stand? Dig Dis 24:260–266

Waseem S, Moshiree B, Draganov PV (2009) Gastroparesis: current diagnostic challenges and management considerations. World J Gastroenterol 15:25–37

Brody F, Vaziri K, Saddler A et al (2008) Gastric electrical stimulation for gastroparesis. J Am Coll Surg 207:533–538

McKenna D, Beverstein G, Reichelderfer M et al (2008) Gastric electrical stimulation is an effective and safe treatment for medically refractory gastroparesis. Surgery 144:566–572

Gould JC, Dholakia C (2009) Robotic implantation of gastric electrical stimulation electrodes for gastroparesis. Surg Endosc 23:508–512

Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D et al (2003) Development and validation of a patient assessed gastroparesis symptom severity measure: the gastroparesis cardinal symptom index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 18:141–150

Lin Z, Sarosiek I, Forster J et al (2006) Symptom responses, long-term outcomes and adverse events beyond 3 years of high-frequency gastric electrical stimulation for gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 18:18–27

Ayinala S, Batista O, Goyal A et al (2005) Temporary gastric electrical stimulation with orally or PEG-placed electrodes in patients with drug refractory gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc 61(3):455–461

Lin Z, Forster J, Sarosiek I et al (2004) Treatment of diabetic gastroparesis by high-frequency gastric electrical stimulation. Diabetes Care 27(5):1071–1076

Maranki JL, Lytes V, Meilahn JE et al (2008) Predictive factors for clinical improvement with Enterra gastric electric stimulation treatment for refractory gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci 53:2072–2078

Abidi N, Starkebaum WL, Abell TL (2006) An energy algorithm improves symptoms in some patients with gastroparesis and treated with gastric electrical stimulation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 18:334–338

Velanovich V (2008) Quality of life and symptomatic response to gastric neurostimulation for gastroparesis. J Gastrointest Surg 12(10):1656–1662

Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I et al (1998) Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci 43(11):2398–2404

Lin Z, Hou Q, Sarosiek I et al (2008) Association between changes in symptoms and gastric emptying in gastroparetic patients treated with gastric electrical stimulation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20:464–470

McCallum RW, Dusing RW, Sarosiek I et al (2006) Mechanisms of high-frequency electrical stimulation of the stomach in gastroparetic patients. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 1:5400–5403

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Musunuru, S., Beverstein, G. & Gould, J. Preoperative Predictors of Significant Symptomatic Response After 1 Year of Gastric Electrical Stimulation for Gastroparesis. World J Surg 34, 1853–1858 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0586-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0586-1