Abstract

Objective

This study was designed to assess the incidence of peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) in a population-based cohort of men aged 55–74 years and to establish a predictive function based on risk factors for the disease.

Methods

This was a prospective study of 699 men representative of an urban population. Cardiovascular risk factors, history of cardiovascular events, and ankle-brachial index (ABI) at baseline and at 5 years were measured. PAOD was defined as a confirmed ABI <0.9.

Results

A total of 468 (67%) subjects could be evaluated at 5 years. In the remaining 233 subjects, 94 had PAOD at baseline, 66 died during the study, and 73 were lost to follow-up. At the end of the 5-year study period, 56 (12%) subjects developed PAOD (21.4% ABI <0.6, 78.6% ABI between 0.61 and 0.9). Independent predictors for PAOD were age older than 70 years at baseline (odds ratio [OR] 2.5, P = 0.004), smoking history more than 40 pack-year (OR = 2.27, P = 0.007), history of cerebrovascular disease (OR = 3.49, P = 0.02), and symptomatic coronary disease (OR = 3.36, P = 0.004). The 5-year incidence of PAOD was 22.4% for subjects older than 70 years, 21.5% for heavy smokers, 29.4% for those with previous cerebrovascular events, and 25% for subjects with ischemic heart disease. The risk for PAOD in subjects without risk factors was 6%.

Conclusions

Twelve percent of adult men aged between aged 55 and 74 years developed PAOD during a follow-up of 5 years. Besides subjects with history of cardiovascular disease, men older than aged 70 years and heavy smokers constituted a high-risk group for PAOD and, therefore, the object of directed efforts of primary prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) is an important cause of quality of life impairment in older adults and has been strongly associated with cardiovascular events and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [1–4]. Knowledge about prevalence, risk factors, and outcome of subjects with PAOD has largely emerged from epidemiological studies performed during the last two decades, when PAOD received the attention of cardiovascular epidemiologists [5–8]. Although these data have raised the recognition of PAOD as an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease, there remains epidemiological issues related to PAOD that are poorly studied, such as the risk for PAOD development among the general population.

The incidence and risk factors for PAOD have been evaluated in limited number of epidemiological surveys [9–14], rarely by means of an objective measurement, such as the Doppler ankle-brachial index, and never with further confirmation of suspected cases by a vascular surgeon or vascular laboratory. Further precise data on this topic would allow researchers to establish a better estimate of the risk of developing PAOD in the general population and to develop strategies for primary prevention of the disease.

The “Pubilla Casas Artery Study” was a longitudinal study with the objective of establishing the incidence and risk factors for PAOD assessed by the ankle-brachial index (ABI) in a population-based cohort of 699 adult healthy men from an urban district in the neighborhood of Barcelona, Spain [15–17]. All participants underwent reassessment by means of ABI at 5 years after inclusion in the cohort. The objective of this study was to determine the incidence of PAOD and to establish a predictive function based on the presence of risk factors for PAOD.

Methods

Study population

The target population included all men aged 55–74 years of Pubilla Casas, an urban neighborhood nearby Barcelona, Spain. At the time of recruitment (1996–1997), 3,500 of all Pubilla Casas inhabitants were men in this age stratum, 85% of whom were registered in the lists of the Pubilla Casas Primary Care Centre, attended by 14 general practitioners. All male subjects (except those with mental impairment or terminal diseases) attended by four of these general practitioners were recruited. To improve generalizability, a 4/14 random sample of the 15% unregistered male population of this district was added. This sampling method, more detailed elsewhere [17], yielded 900 eligible men for the study, 708 of which agreed to participate. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Baseline measurements

The participating physicians evaluated cardiovascular risk factors and the presence of PAOD at the time of recruitment. Risk factors included age, body mass index (BMI), cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipemia (serum cholesterol and triglycerides). Previous symptomatic disease in other vascular territories (coronary heart disease or cerebrovascular events) was recorded by medical history, review of hospital discharge forms, or results of medical evaluation performed by a cardiologist or a neurologist.

PAOD was assessed by rest ABIs performed by the four previously mentioned general practitioners, using a calibrated mercury sphygmomanometer and a handheld Doppler device. Current or past symptoms suggestive of PAOD also were recorded. Subjects with any ABI <0.9 or current or past PAOD symptoms were referred to the Department of Vascular Surgery of Hospital del Mar for confirmation. At the hospital, data of the patient’s medical record were evaluated by a vascular surgeon and patients underwent ABI, which was performed in the vascular laboratory. Definitive diagnosis of PAOD was established when an ABI <0.9 was confirmed independently of clinical manifestations. Nine patients had abnormal ABIs (>1.5), suggestive of arterial calcification and were excluded from the study.

Follow-up

Subjects were followed for 5 years at the Primary Care Centre by the four general practitioners. Standard care was provided with the goal of controlling cardiovascular risk factors, including cessation of smoking. ABIs were again performed in all subjects 5 years after recruitment (except those who died or subjects lost to follow-up). A definitive diagnosis of PAOD was established according to the same criteria used at baseline (confirmed ABI <0.9).

Statistical analysis

The association of PAOD development with baseline risk factors was assessed by crude event rates and logistic regression. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. To control for potential confounding factors, all variables related to PAOD (at baseline or at 5-year measurements) with P < 0.10 in the bivariate analyses were considered in the logistic regression. Statistically nonsignificant variables not modifying beta-coefficients were retrieved from the model to increase statistical power.

To estimate risk of developing PAOD at 5 years, a predictive function based on event probability calculated with the logistic regression model was done. The validity of the model was assessed on the basis of its calibration (Hosmer-Lemershow test) and its discrimination (ROC curve). All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 14.0).

Results

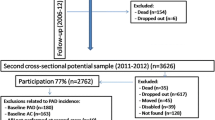

A total of 699 men were included in the study. Ninety-four (13.4%) patients had PAOD in baseline assessment, 71 (10.1%) were lost at follow-up, and 66 (9.4%) died before 5-year evaluation, of which 30 (45.5%) were cardiovascular-related. Therefore, measurements at baseline and at 5-year follow-up were available for 468 participants. The mean age of these patients was 64.2 years; 48.9% were ex-smokers and 27.8% current smokers. Other cardiovascular risk factors included hypertension in 53.6% of cases, diabetes mellitus in 20.1%, serum LDL-cholesterol levels >4 mmol/l in 33.5%, and total serum cholesterol levels >5.2 mmol/l in 70.7%. Previous ischemic cerebrovascular and coronary events were recorded in 17 (3.6%) and 32 (6.8%) patients, respectively.

The prevalence of risk factors in subjects who died during follow-up was not significantly different than that of patients who finished the study. However, subjects who were lost to follow-up were older, the percentage of current smokers was greater, and the prevalence of cardiovascular events and cerebrovascular disease was higher.

At 5-year follow-up, 56 (11.9%) subjects had developed PAOD, of whom 21.4% had ABIs <0.6. Within this group, 40 subjects were asymptomatic, 11 had symptoms of intermittent claudication, and 1 patient had critical ischemia. The PAOD incidence was 23.8 per 1,000 persons per year.

When subjects with and without incident PAOD were compared, those with PAOD were older (mean, 66.4 vs. 63.9 years; P = 0.01), had an increased prevalence of some cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes (30.4% vs. 18.7%, P = 0.04), heavy smoking habit (>40 pack-year; 41.1% vs. 26%, P = 0.01), previous ischemic heart disease (14% vs. 5.8%, P = 0.01), and previous cerebrovascular event (9.8% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.04; Table 1). Regarding baseline medication, subjects with newly diagnosed PAOD were more frequently prescribed antiplatelet agents (17.3% vs. 7.7%, P = 0.03) and anticoagulants (5.3% vs. 0.2%, P < 0.01; Table 2).

In the multivariate analysis, age older than 70 years (odds ratio [OR] 2.5, P = 0.04), smoking habit >40 pack-year (OR = 2.2, P < 0.01), previous cerebrovascular events (OR = 3.4, P = 0.02), and previous ischemic heart disease (OR = 3.3, P < 0.01) at baseline were significant risk factors independently associated with the development of PAOD (Table 3). The incidence of PAOD at 5 years was 22.4% for subjects older than aged 70 years, 21.5% for heavy smokers, 29.4% for patients with previous cerebrovascular events, and 25% for patients with history if ischemic heart disease. The risk for PAOD in subjects in whom all these risk factors were absent was only 6%.

To assess the calibration of the logistic regression model, the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test was performed. The results was not significant (P = 0.59), indicating proper calibration of the model. As for discrimination, the ROC curve was significant (P < 0.001; 95% confidence interval, 0.593–0.749), indicating enough capability to predict probability to develop PAOD. Indeed, PAOD risk at 5 years for subjects sharing the four independent risk factors was as high as 76%.

Discussion

At the beginning of the study, 13.4% of subjects had PAOD. This finding was consistent with previous studies reporting PAOD prevalence in men older than aged 55 years from 11–18% [7, 18–20]. Of the remaining cohort of non-PAOD adult elderly older men followed 5 years, 12% developed the disease. The actual incidence could have been higher, because subjects lost to follow-up showed higher prevalence of some risk factors associated with PAOD. The present findings showed that men older than aged 70 years, with smoking history of >40 pack-year, and previous cardiovascular events or stroke were at high risk of PAOD. Accordingly, male subjects in whom one of these risk factors is present constitute a population group that should be targeted for primary prevention of PAOD. Similarly to that observed in previous studies [21, 22], the majority of subjects with new diagnosed PAOD were asymptomatic. Screening based on claudication questionnaires may therefore identify only a subset of all those PAOD subjects suitable for cardioprotective medications. Because all PAOD subjects—both symptomatic and asymptomatic—share an increased risk of morbidity and mortality, noninvasive screening by means of ABI maximizes any cardioprotective strategy in these patients.

In the present cohort, the incidence of PAOD was 23.8 per 1,000 persons per year, which is slightly higher than the incidence rate of 17.8 per 1,000 persons per year reported in the Limburg study [10]. In men aged 55–74 years, the Framingham and Edinburgh Artery Studies showed an incidence of intermittent claudication at 5 years of 2.5% and 3.2%, respectively [8, 11]. Because the proportion of symptomatic PAOD in our cohort was 21.4%, the incidence rate of intermittent claudication also was 2.5% at 5 years, which is consistent with that reported in these studies.

In these studies, age, sex, smoking habit, and previous cardiovascular events were the most frequent risk factors associated with symptomatic or asymptomatic PAOD development. These results were consistent with our findings. However, the Framingham, Limburg, and Quebec Cardiovascular studies also found association of PAOD with hypertension and diabetes [8, 10, 14]. These results were not observed within our population of study, which may be explained by the sample size or characteristics of the cohort. PAOD rates found in our study cannot be attributed to medication because no statistical significance was found according to lipid-lowering and antihypertensive intake. Furthermore, antiplatelet and anticoagulant intake rates were even higher among those who later developed PAOD, thus reflecting a higher prevalence of previous coronary heart or cerebrovascular diseases among them.

The estimation of incidence rates relies on the time of disease occurrence. This exact time was not known in our study because the time lapse between both ABI measurements was 5 years. We considered our population of study as a constant cohort, being possible an underestimation of the reported incidence rates. Incidence data about every risk factor subgroup allowed us to develop a mathematical function for measuring the individual risk. In a similar way than that of coronary risk, equations were developed some decades ago with the Framingham cohort, PAOD prevention based on risk functions may allow for a better preventive decision-making than any other approach. Although our study population may represent only Mediterranean adult elderly men, our results suggest an incidence rate of PAOD close to that observed in other countries with higher incidence of coronary heart disease. This finding underscores the importance of the relative weight and prevalence of each risk factor in each of the clinical forms of atherothrombosis.

Our findings should be interpreted by taking into account some limitations: the small number of patients in each subgroup is probably the most important. To partly compensate for this limitation, exhaustive care was taken when considering each risk factor and each PAOD diagnosis at baseline or follow-up. This included general practitioner clinical history, hospital records review, tobacco consumption questionnaires, lipid-lowering medication wash out, except for those on secondary prevention among others, and PAOD noninvasive measurements and confirmation of any PAOD diagnosis at baseline and follow-up by a vascular surgeon.

In summary, 12% of adult men aged 55–74 years developed PAOD during a follow-up of 5 years. Beyond subjects with history of cardiovascular disease, men older than aged 70 years and heavy smokers constitute a high-risk group for PAOD development and, therefore, the object of directed efforts of primary prevention.

References

Newman AB, Shemanski L, Manolio TA, Cushman M, Mittelmark M, Polak JF, Powe NR, Siscovick D (1999) Ankle-arm index as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The Cardiovascular Health Study Group. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol 19:538–545

Hooi JD, Kester AD, Stoffers HE, Rinkens PE, Knottnerus JA, van Ree JW (2004) Asymptomatic peripheral arterial occlusive disease predicted cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in a 7-year follow-up study. J Clin Epidemiol 57:294–300

O’Hare AM, Katz R, Shlipak MG, Cushman M, Newman AB (2006) Mortality and cardiovascular risk across the ankle-arm index spectrum: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 113:388–393

Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration (2008) Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA 300:197–208

Criqui MH, Browner D, Fronek A, Klauber MR, Coughlin SS, Barrett-Connor E et al (1989) Peripheral arterial disease in large vessels is epidemiologically distinct from small vessel disease. An analysis of risk factors. Am J Epidemiol 129(6):1110–1119

McDermott MM, Kerwin DR, Liu K, Martin GJ, O’Brien E, Kaplan H et al (2001) Prevalence and significance of unrecognized lower extremity peripheral arterial disease in general medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med 16:384

Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett-Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D (1985) The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation 71(3):510–515

Murabito JM, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Wilson WF (1997) Intermittent claudication. A risk profile from The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 96:44–49

Kannel WB, Skinner JJ Jr, Schwartz MJ, Shurtleff D (1970) Intermittent claudication. Incidence in the Framingham Study. Circulation 41:875–883

Hooi JD, Kester AD, Stoffers HE, Overdijk MM, van Ree JW, Knottnerus JA (2001) Incidence of and risk factors for asymptomatic peripheral arterial occlusive disease: a longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol 153:666–672

Leng GC, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG, Whiteman M, Dunbar J, Housley E, Ruckley CV (1996) Incidence, natural history and cardiovascular events in symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol 25:1172–1181

Widmer LK, Biland L (1985) Incidence and course of occlusive peripheral artery disease in geriatric patients. Possibilities and limits of prevention. Int Angiol 4:289–294

Kannel WB, McGee DL (1985) Update on some epidemiologic features of intermittent claudication: the Framingham Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 33:13–18

Dagenais GR, Maurice S, Robitaille NM, Gingras S, Lupien PJ (1991) Intermittent claudication in Quebec men from 1974–1986: the Quebec Cardiovascular Study. Clin Invest Med 14:93–100

Merino J, Planas A, De Moner A, Gasol A, Contreras C, Marrugat J, Vidal-Barraquer F, Clarà A (2008) The association of peripheral arterial occlusive disease with major coronary events in a mediterranean population with low coronary heart disease incidence. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 36(1):71–76

Planas A, Clará A, Marrugat J, Pou JM, Gasol A, de Moner A, Contreras C, Vidal-Barraquer F (2002) Age at onset of smoking is an independent risk factor in peripheral artery disease development. J Vasc Surg 35(3):506–509

Planas A, Clará A, Pou JM, Vidal-Barraquer F, Gasol A, de Moner A, Contreras C, Marrugat J (2001) Relationship of obesity distribution and peripheral arterial occlusive disease in elderly men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25(7):1068–1070

Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Manolio TA, Polak J, Fried LP, Borhani NO et al (1993) Ankle-arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Heart Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Circulation 88:837–845

Stoffers HE, Rinkens PE, Kester AD, Kaiser V, Knottnerus JA (1996) The prevalence of asymptomatic and unrecognized peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Int J Epidemiol 25:282–290

Schroll M, Munk O (1981) Estimation of peripheral arteriosclerosis disease by ankle blood pressure measurements in a population of 60 year old men and women. J Chronic Dis 34:261–269

Meijer WT, Hoes AW, Rutgers D, Bots ML, Hofman A, Grobbee DE (1998) Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18(2):185–192

Fowkes FG, Housley E, Cawood EH, Macintyre CC, Ruckley CV, Prescott RJ (1991) Edinburgh Artery Study: prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol 20(2):384–392

Conflicts of interest statement

Not declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Merino, J., Planas, A., Elosua, R. et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease in a Prospective Cohort of 700 Adult Elderly Men Followed for 5 Years. World J Surg 34, 1975–1979 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0572-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0572-7