Abstract

Background

Nasogastric decompression has been routinely used in most major abdominal operations to prevent the consequences of postoperative ileus. The aim of the present study was to assess the necessity for routine prophylactic nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression after gastrectomy.

Methods

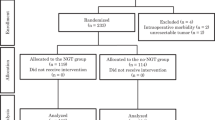

A prospective randomized trial included 84 patients undergoing elective partial or total gastrectomy. The patients were randomized to a group with a postoperative nasogastric or nasojejunal tube (Tube Group, n = 43) or to a group without a tube (No-tube Group, n = 41). Gastrointestinal function, postoperative course, and complications were assessed.

Results

No significant differences in postoperative mortality or morbidity, especially fistula or intra-abdominal sepsis, were observed between the groups. Passage of flatus (P < 0.01) and start of oral intake (P < 0.01) were significantly delayed in the Tube Group. Duration of postoperative perfusion (P = 0.02) and length of hospital stay (P = 0.03) were also significantly longer in the Tube Group. Rates of nausea and vomiting were similar in the two groups. Moderate to severe discomfort caused by the tube was observed in 72% of patients in the Tube Group. Insertion of a nasogastric or nasojejunal tube was necessary in 5 patients in the No-tube Group (12%).

Conclusions

Routine prophylactic postoperative nasogastric decompression is unnecessary after elective gastrectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Nasogastric intubation was initially introduced by Levin1 in 1921, and its use in the treatment of acute intestinal obstruction and postoperative ileus was popularized by Wangensteen and Paine2 during the 1930s. Until relatively recently, nasogastric decompression was routinely used in most major intra-abdominal operations. Nasogastric intubation was thought to decrease postoperative ileus (nausea, vomiting, and gastric distension), wound and respiratory complications, and to reduce the incidence of anastomotic leaks after gastrointestinal surgery.3 However, the necessity of nasogastric decompression following elective abdominal surgery has been increasingly questioned over the last several years. Many clinical studies have suggested that this practice does not provide any benefit but could increase patient discomfort and respiratory complications.4–6 Furthermore, meta-analyses have concluded that routine nasogastric decompression is no longer warranted after elective abdominal surgery.7,8

After gastrectomy, nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression has been considered necessary to prevent the consequences of postoperative ileus (anastomotic leakage or leaking from the duodenal stump). For this reason, the nasogastric tube is usually left in place for a few days after the procedure. Few studies have actually assessed this common practice. Three prospective studies from Taiwan9 and Korea10,11 have suggested that there is no need for a nasogastric tube after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Only one European multicenter prospective study has been performed to assess the use of a nasojejunal tube after total gastrectomy.12 The authors have not reported any differences between the two groups, with or without nasojejunal postoperative decompression, concerning mortality, morbidity, and postoperative course.12 However, to our knowledge, no European, single-center, controlled trial is available concerning both total and partial gastrectomy. The aim of this study, therefore, was to evaluate, in a prospective randomized trial, the necessity for a nasogastric tube after gastrectomy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From May 1995 to May 2002, 84 patients undergoing elective partial or total gastrectomy for carcinoma or benign disease were included in this study, which was approved by the ethical committee of our hospital. Informed consent was obtained from the patients before they were entered into the study. Patients with emergency surgery, history of abdominal irradiation, additional resection of adjacent organs, or technical operative difficulties (duodenal, pancreatic, or vascular injury) were excluded.

The extent of gastric resection was a subtotal gastrectomy for cancers of the lower third and total gastrectomy for cancers of the middle and superior thirds. A radical lymphadenectomy without splenectomy and pancreatectomy (modified D2 procedure) was performed in all patients undergoing gastrectomy for cancer. Digestive continuity was restored by a Billroth I gastroduodenostomy or Billroth II gastrojejunostomy after partial gastrectomy, and a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop after total gastrectomy (esophagojejunostomy).

All patients had a 14- or 16-French nasogastric tube inserted by the anesthetist during the procedure. At the end of the operation, each patient entered into the study was randomized either to a group with a nasogastric or nasojejunal tube (Tube Group) or to a group without a tube (No-tube Group). For the randomization, a binder of questionnaires that randomly and sequentially determined the groups had been built before the beginning of the study using computer-generated random numbers. At the end of the operation, the anesthetist took the questionnaire corresponding to the patient number in the binder and unfolded the previously folded and stapled right upper corner, thereby revealing the determined allotment.13 In the Tube Group the tube was left in for continuous drainage until passage of flatus or stool, at least 36 hours postoperatively. In the No-tube Group the tube was removed at the end of the operation when the patient was in the recovery room. Postoperative oral intake was restricted for all patients until the passage of flatus in the absence of abdominal distension, nausea, or vomiting. Patients were allowed clear water to drink after resolution of the ileus, and they then progressed to a liquid diet and a semi-solid diet when water was tolerated for more than 24 hours. In the Tube Group, the tube was removed after the passage of flatus, and patients were allowed water about 6 hours later. Diet was increased in the same stepwise fashion in the two groups, from clear liquids to soft food, as tolerated. A nasogastric or nasojejunal tube was inserted in patients in the No-tube Group, or reinserted in patients in the Tube Group, only if they developed a clinical need for decompression (i.e., repeated episodes of vomiting or abdominal distension), as determined in the postoperative period by the attending physician. All patients received short-term perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis with a third-generation cephalosporin and a subcutaneous injection of low-molecular-weight heparin sodium as deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis.

The postoperative course of each patient was closely monitored. The day of passage of flatus and oral food intake, the duration of nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression, postoperative perfusions, and length of hospital stay were recorded. Mortality, abdominal complications (generalized peritonitis, deep abscesses, obvious fistulas, wound complications), pulmonary complications (pneumonia, atelectasis), postoperative fever, nausea, and vomiting, tube insertion or reinsertion, and discomfort from the tube (ear pain, nasal soreness, painful swallowing) were noted. Perioperative mortality included deaths within the first 30 days after surgery or during the original hospital stay if longer. Fistula was defined as a proven leak at water-soluble contrast radiographic examination, or a leak of clinical significance necessitating reoperation. Postoperative fever was defined as two body temperatures greater than 38°C taken at least 12 h apart, starting more than 24 h after operation. Intravenous perfusions were maintained until resumption of oral feeding. The degree of discomfort from the tube, as reported by the patient, was graded on a scale from 0 to 3 (absence of discomfort or slight, moderate, or severe discomfort).

The primary objective for comparison was the difference in postoperative course determined by continuous variables (time to first passage of flatus, first oral intake, duration of postoperative perfusions, postoperative hospital stay). Before the study was initiated, it had been determined that at least 40 patients were needed per arm to have an 80% chance of detecting a 10% difference in the continuous variables. A much larger sample size of 250 patients per arm would have been needed to get an 80% chance of detecting a 10% difference in the complication rates. Categorical variables were compared within groups using the χ2 test with Yates correction or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed by Student’s t-test, whereas non-normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test. All statistical analyses were performed using computer software StatView (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM), unless stated otherwise. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The study group included 84 patients, 45 males and 39 females, with a mean age of 66.6 ± 1.2 years. There were 43 patients enrolled in Tube Group and 41 in No-tube Group. The patient data in the two groups are summarized in Table 1. The two groups were comparable with respect to age and sex distribution, type of disease, and operation performed.

Table 2 summarizes the gastrointestinal outcome and postoperative course. On average, the tube was maintained for 3.9 ± 0.3 days (range: 1.5–15 days) after surgery in the Tube Group. Time to first passage of flatus and time to first oral intake were significantly longer among patients in Tube Group than among patients in the No-tube Group (4.5 ± 0.2 days versus 3.7 ± 0.2 days and 5.8 ± 0.3 days versus 4.7 ± 0.2 days, respectively). Duration of postoperative perfusions and postoperative stay were also significantly longer in patients in theTube Group compared with patients in the No-tube Group (7.0 ± 0.4 days versus 5.8 ± 0.3 days and 12.4 ± 0.7 days versus 9.8 ± 1.0 days, respectively). The incidence of nausea and vomiting was higher in the No-tube Group than in the Tube Group (29% versus 21%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Because of subocclusive symptoms, nasogastric tube insertion was necessary in 5 patients among the 41 included in the No-tube Group (12%), whereas 3 patients in the Tube Group, who already had their tubes removed, needed reinsertion of the drain on the third to fifth postoperative day. In the Tube Group, 31 patients (72%) complained of moderate to severe discomfort caused by the presence of the tube, particularly because of dysphagia and nasal soreness. In the No-tube Group, 4 patients among the 5 who needed tube insertion also complained of discomfort associated with the tube. Thus, The nasogastric tube caused moderate to severe discomfort in 73% of the patients who effectively had a tube. A total of 3 patients in Tube Group had their tubes removed before the passage of flatus just because of severe discomfort from the drain.

As shown in Table 3, no significant difference in postoperative complications was observed between the groups. Three patients died during the first 30 postoperative days: one patient in the Tube Group and two patients in the No-tube Group. In the Tube Group, one patient with partial gastrectomy died on the fifteenth postoperative day from intra-abdominal sepsis due to a leak from the duodenal stump. In the No-tube Group, one patient with total gastrectomy died on the tenth postoperative day from intra-abdominal and pulmonary sepsis due to an anastomotic leak. An intra-abdominal abscess was treated by percutaneous drainage on the eighth postoperative day. Despite this treatment, pulmonary sepsis occurred, with bilateral pneumonia and pulmonary failure leading to death two days later. Another patient in the No-tube Group died from acute pancreatitis on the thirteenth postoperative day after partial gastrectomy. Intra-abdominal complications (fistula, peritonitis, abscess), including anastomotic leaks and leakage from the duodenal stump, occurred equally in the two groups. Furthermore, no significant difference in the incidence of wound complications (infection, disruption), pulmonary complications (pneumonia, atelectasis), and febrile morbidity was noted between the groups. All patients in the No-tube Group with an anastomotic leak (n = 2) underwent placement of a nasojejunal tube after diagnosis of the complication. The postoperative course of patients with digestive fistula was similar in the two groups, with a death in each group and complete resolution of the complication in the other cases (n = 3).

Concerning management of the digestive fistula, 3 patients (2 in the Tube Group, and 1 in the No-tube Group) needed reoperation, while the others were treated conservatively (n = 2). When the patient with esophagojejunostomy leak in the No-tube Group was reoperated on, a purulent peritonitis was found, but no significant jejunal contamination was noticed.

DISCUSSION

Since the introduction of the nasogastric tube and despite the lack of studies to support its theoretical advantages, nasogastric decompression has become surgical dogma after major abdominal operations. Many surgeons have routinely used nasogastric decompression to reduce the risk of postoperative complications including vomiting, wound dehiscence, and anastomotic leak. However, during the last decade, many studies have argued against the necessity of nasogastric tube following general abdominal surgery, particularly after gynecologic and colorectal procedures.4–6,14–16 In 1995, a meta-analysis by Cheatham et al.7 about nasogastric decompression after elective laparotomy, analyzed 26 clinical trials (3,964 patients) that met quality inclusion criteria. Days to first oral intake were significantly fewer, and incidence of pulmonary complications and postoperative fever were significantly lower in patients managed without nasogastric tubes, whereas routine nasogastric decompression did not decrease the incidence of any other complication. The most recent meta-analysis, published 10 years later by Nelson et al.,8 partly confirmed these results. Twenty-eight studies, including 4,194 patients, fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were analyzed. Patients not having a nasogastric tube routinely inserted experienced an earlier return of bowel function (P < 0.001), a marginal decrease in pulmonary complications (P = 0.07), and a marginal increase in wound infection (P = 0.08) and ventral hernia (P = 0.09). Anastomotic leakage was similar in the two groups (P = 0.70). The authors concluded that routine nasogastric decompression should be abandoned in favor of selective use of the nasogastric tube.

After gastrectomy, prophylactic nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression has been considered differently from decompression elsewhere in the abdomen, because the formation of proximal anastomoses (esophagojejunal, gastrojejunal, or gastroduodenal anastomoses), and the duodenal stump may be potential risk factors for developing digestive fistula during the early postoperative period. Furthermore, in cases of gastric cancer, radical gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection (with or without splenectomy) may severely impair intestinal motility after operation, by sectioning sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers, particularly along the celiac axis.3,17 For these reasons, until recently, nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression has been a routine part of perioperative care after radical gastrectomy.

Few studies have questioned the role of nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression after gastrectomy. In the present study, we found that in patients with gastrectomy, contrary to “popular belief,” the use of nasogastric or nasojejunal tube actually delayed passage of flatus, start of oral intake, and general recovery.

Three prospective studies from Far Eastern centers with a high case volume in Taiwan9 and Korea10,11 have suggested that there is no need for a nasogastric tube after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Our results, in a low-volume Western center, are close to those reported in these studies. Yoo et al.10 in a prospective trial including 136 patients undergoing radical gastrectomy for cancer have also found that time to passage of flatus, time to taking liquid diet, and postoperative hospital stay were all significantly shorter in the no-decompression group. Previous published studies of patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal surgery have reported similar results. In a prospective randomized trial including 74 patients who underwent partial gastrectomy for cancer with extensive D2 lymphadenectomy, Wu et al.9 concluded that the use of a nasogastric tube neither increased nor decreased morbidity or mortality but prolonged significantly the median postoperative hospital stay (16 days versus 12 days). Thus, the consequences of ileus and the risk of anastomotic leakage have probably been overestimated after gastrectomy without nasogastric decompression. A nasogastric or nasojejunal tube did not improve postoperative outcome after gastrectomy, as it was already reported after bowel anastomosis.5

Only one European multicenter prospective study has been performed to assess the use of a nasojejunal tube after total gastrectomy.12 In that study 237 patients undergoing total gastrectomy for gastric cancer were randomly assigned for nasojejunal placement or not. The authors did not report any differences between the groups, with or without nasojejunal postoperative decompression, concerning mortality, morbidity, and postoperative course.12 Likewise, in the present study, mortality and morbidity rates did not differ between patients of Tube Group and those of No-tube Group. However, this study was underpowered to demonstrate any differences in complication rate, particularly fistula rate, which ranged from 1% to 6% in the most recent reports.10,12 Considering the low incidence of postoperative intra-abdominal complications, several hundred patients should be required to identify significant differences in the complication rates. Such a trial seems impossible to perform over a short period in a single Western center.7 Despite these limitations, our results suggest that routine prophylactic postoperative nasogastric or nasojejunal decompression is unnecessary after gastrectomy.

Concerning the intraoperative findings of the patient with esophagojejunostomy leak in the No-tube Group, a purulent peritonitis was noticed, but there was no significant jejunal contamination at the time of reoperation. We do not consider that the presence of a nasojejunal tube would have been able to prevent this complication. More generally, the outflow of the nasojunal tube after total gastrectomy was usually very poor (<50 ml/day, data not shown), which strengthens the argument against the utility of routine nasojejunal decompression after gastrectomy.

On the other hand, 73% of intubated patients complained of important discomfort caused by the tube in our study, essentially because of nasal soreness and hindered deglutition. The discomfort caused by the tube is one of the most unpleasant aspects of the postoperative course that has been reported in nearly all published trials.5–8,10,14,15 Moreover, a nasogastric tube itself may induce vomiting and may be associated with several complications, such as otitis, sinusitis, esophagitis, or gastroesophageal reflux.3,18 Because of subocclusive symptoms, nasogastric tube insertion was necessary in only 5 patients among the 41 included in the No-tube Group (12%) in our trial, whereas nasogastric tube insertion was required in 5% –% in the meta-analysis by Cheatham et al.7 concerning general abdominal surgery.

These results and data from the literature indicate that there is no rationale for routine use of a nasogastric or nasojejunal tube after gastrectomy. Patients undergoing gastrectomy may avoid prophylactic tube placement, which should be used only when symptoms develop. In this era of cost containment, this approach may also represent a cost-effective strategy. By not placing nasogastric tubes routinely, each hospital may realize significant saving, not only of the cost of the tube and its management but also because of shortened hospital stay. As described in patients undergoing colorectal surgery,19,20 the next step toward simplifying the postoperative course after gastrectomy could be early postoperative feeding, and further studies are required to assess this possibility.

References

Levin AL. A new gastroduodenal catheter. JAMA 1921;76:1007–1009

Wangensteen OH, Paine JR. Treatment of acute intestinal obstruction by suction with the duodenal tube. JAMA 1933;101:1532–1539

Sagar PM, Kruegener G, MacFie J. Nasogastric intubation and elective abdominal surgery. Br J Surg 1992;79:1127–1131

Wolff BG, Pembeton JH, van Heerden JA, et al. Elective colon and rectal surgery without nasogastric decompression. A prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg 1989;209:670–673

Cunningham J, Temple WJ, Langevin JM, et al. A prospective randomized trial of routine postoperative nasogastric decompression in patients with bowel anastomosis. Can J Surg 1992;35:629–632

Savassi-Rocha PR, Conceicao SA, Ferreira JT, et al. Evaluation of the routine use of the nasogastric tube in digestive operation by a prospective controlled study. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1992;174:317–320

Cheatham ML, Chapman WC, Key SP, et al. A meta-analysis of selective versus routine nasogastric decompression after elective laparotomy. Ann Surg 1995;221:469–476

Nelson R, Tse B, Edwards S. Systematic review of prophylactic nasogastric decompression after abdominal operations. Br J Surg 2005;92:673–680

Wu CC, Hwang CR, Liu TJ. There is no need for nasogastric decompression after partial gastrectomy with extensive lymphadenectomy. Eur J Surg 1994;160:369–373

Yoo CH, Son BH, Han WK, et al. Nasogastric decompression is not necessary in operations for gastric cancer: prospective randomised trial. Eur J Surg 2002;168:379–383

Lee JH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH. Comparison of gastric cancer surgery with versus without nasogastric decompression. Yonsei Med J 2002;43:451–456

Doglietto GB, Papa V, Tortorelli AP, et al. Nasojejunal tube placement after total gastrectomy: a multicenter prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg 2004;139:1309–1313

Cancer Research Campaign Working Party. Trials and tribulations: thoughts on the organization of multicentre clinical studies. Br Med J 1980;281:918–920

Nathan BN, Pain JA. Nasogastric suction after elective abdominal surgery: a randomised study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1991;73:291–294

Pearl ML, Valea FA, Fischer M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of postoperative nasogastric tube decompression in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 88:399–402

Otchy DP, Wolff BG, van Heerden JA, et al. Does the avoidance of nasogastric decompression following elective abdominal colorectal surgery affect the incidence of incisional hernia? Results of a prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum 1995;38:604–608

Inoue K, Fuchigami A, Higashide S, et al. Gallbladder sludge and stone formation in relation to contractile function after gastrectomy. A prospective study. Ann Surg 1992;215:19–26

Manning BJ, Winter DC, McGreal G, et al. Nasogastric intubation causes gastroesophageal reflux in patients undergoing elective laparotomy. Surgery 2001;130:788–791

Basse L, Hjort Jakobsen D, Billesbolle P, et al. A clinical pathway to accelerate recovery after colonic resection. Ann Surg 2000;232:51–57

Kehlet H, Buchler MW, Beart RW, Jr, et al. Care after colonic operation—is it evidence-based? Results from a multinational survey in Europe and the United States. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202:45–54

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carrère, N., Seulin, P., Julio, C.H. et al. Is Nasogastric or Nasojejunal Decompression Necessary after Gastrectomy? A Prospective Randomized Trial. World J. Surg. 31, 122–127 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-006-0430-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-006-0430-9