Abstract

Background

The purpose of this clinical study was to evaluate the efficacy of laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with perforated appendicitis.

Methods

This study involved a total of 73 consecutive patients who had undergone appendectomy for perforated appendicitis between January 1999 and December 2004. While 39 patients underwent open appendectomy (OA) during the first 3 years, the remaining 34 patients underwent laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) during the last 3 years.

Results

There was no case of LA converted to OA. No significant difference was found in the operating time between the two groups. Laparoscopic appendectomy was associated with less analgesic use, earlier oral intake restart (LA, 2.6 days; OA, 5.1 days), shorter median hospital stay (LA, 11.7 days; OA, 25.8 days), and lower rate of wound infections (LA, 8.8%; OA, 43.6%).

Conclusions

These results suggest that LA for perforated appendicitis is a safe procedure that may prove to have significant clinical advantages over conventional surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Numerous prospective randomized studies, meta-analyses, and systematic critical reviews have been published on the subject of laparoscopic appendectomy (LA).1–11 Laparoscopic appendectomy has been associated with statistically significant advantages over open appendectomy (OA) in some outcome measures, such as postoperative physical activity. These benefits of LA, however, appear to be clinically limited or questionable, and consensus concerning the relative advantages of each procedure has not yet been reached.8–11

Appendectomy per se is a relatively less invasive surgery, compared with other digestive surgeries (e.g., cholecystectomy or colectomy), using a small incision and postoperative recovery being usually uneventful. Therefore, LA for uncomplicated appendicitis has struggled to prove its superiority over the open technique. This is in contrast to laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which has promptly become the gold standard for gallstone disease, despite little scientific challenge.

Perforated appendicitis is associated with an increased rate of postoperative abdominal and wound infections. The surgical management of complicated appendicitis generally requires a larger abdominal incision and longer operating time, giving more surgical stress to the patients, compared with that for uncomplicated appendicitis. Moreover, the surgical wound is readily exposed to contaminated fluid, possibly resulting in an increased rate of wound infections. Hence, it is conceivable that LA could represent clinically relevant advantages over OA in patients with perforated appendicitis, because LA is associated with less wound surface area exposed to contamination and potentially facilitates direct visualization during peritoneal lavage. However, whereas several studies have challenged the role of laparoscopy in perforated appendicitis, the results are controversial and the value of LA is not fully estimated.12–21

The purpose of the present clinical study was to evaluate the efficacy of laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with perforated appendicitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

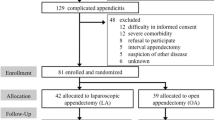

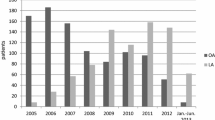

Between January 1999 and December 2004, 586 patients underwent operations for acute appendicitis (Fig. 1). We started to perform laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) for uncomplicated appendicitis in 2001. During this period, a total of 73 consecutive patients underwent appendectomy for perforated appendicitis, including abscess formation or peritonitis diagnosed on CT scan before surgery. Several cases of intra-abdominal abscess treated only by percutaneous drainage were excluded. Since January 2002, LA has been performed in all patients diagnosed on CT scan with complicated appendicitis.

The intraoperative findings, operating time, duration of hospital stay, and postoperative complications were retrospectively checked by reviewing the clinical records of every patient. Thirty-nine patients underwent open appendectomy (OA) during the first 3 years (between January 1999 and December 2001), and 34 patients underwent laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) during the last 3 years (between January 2002 and December 2004). The parameters were compared between the two groups.

All patients received preoperative intravenous antibiotics (mostly second-generation cephalosporin) (Table 1). Laparoscopic appendectomy was performed using a two-handed, three-trocar technique. A 12-mm subumbilical port was introduced by the open method, subsequently creating a pneumoperitoneum. A flexible laparoscope (10-mm, Olympus) was inserted through this trocar. In addition, a 5-mm port was placed in the midline of the lower abdomen and a 10-mm port outside the right rectus muscle at about the level of the umbilicus. The mesoappendix was dissected using an electrocautery or an ultrasound dissector, and the appendix was divided with an Endolinear Cutter. To avoid contamination, the appendix was removed in an endoscopic bag. All of the laparoscopic treatments were done by six surgeons having sufficient experience with laparoscopic surgery (more than 50 cholecystectomy and 20 colectomy cases). Two other surgeons, in addition to the six, were involved in OA, and 12 patients (31%) who underwent OA were operated on by the surgeons who did not participate in LA. The surgeons’ experience in laparoscopic surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis was not included in the qualifications to perform LA for complicated appendicitis.

Open appendectomy was performed through a McBurney incision or pararectal incision, depending on the surgeon’s preference. The mesoappendix was ligated, and the appendiceal stump was ligated and inverted into the cecum with a purse-string suture. The abdominal wall was closed in layers with absorbable sutures, and the skin was closed with single nonabsorbable sutures. Both groups of patients underwent thorough peritoneal lavage using several liters of warm saline until the drainage fluid became clear. Closed suction drains were placed in the abscess cavity encountered. While one of the trocar wounds was used for drainage in LA, the drain was brought out through a stab wound separated from the main abdominal incision in OA.

Analgesics were given intramuscularly (pentazosine) or as a suppository (diclofenac sodium) as needed. Antibiotics were continued or stopped according to the clinical findings. Oral intake was reintroduced as soon as patients could tolerate it and when bowel function became adequate. Postoperative complications were recorded both during hospitalization and at follow-up. The follow-up in the outpatients clinic continued until the patient felt fully recovered with no further postoperative complaints. Data collected also included patient age, sex, body mass index (BMI), preoperative C-reactive protein (CRP) score, operating time, analgesic use frequency, start of oral intake, and the length of postoperative hospital stay. These parameters were summed and compared between the LA and OA groups.

The continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Seventy-three patients underwent appendectomy for perforated appendicitis from 1999 to 2004. The first series for OA consisted of 39 patients, followed by the second series for LA of 34 cases. There was no case of conversion to OA in the laparoscopic group. There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to mean age, gender, preoperative CRP score, abscess formation, and the presence of fecal stones (Table 1).

In the OA group, while in 17 patients (43.6%) the procedure was able to be completed requiring only spinal anesthesia, general anesthesia was needed in 22 patients (56.4%). The clinical outcomes of each procedure are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the operating time between the two groups. We compared the postoperative needs for analgesia in the two groups, and LA presented less analgesic suppository use (LA, 2.1 times; OA, 7.5 times; P < 0.001). Patients in the LA group were able to restart oral intake earlier than those who underwent OA (LA, 2.6 days; OA, 5.1 days; P < 0.05). The duration of abdominal drainage was significantly shorter in LA than in OA. The mean length of postoperative hospital stay was shorter in LA (LA, 11.7 days; OA, 25.8 days; P < 0.001).

There were no deaths in this study. We observed 26 patients (35.6%) who developed postoperative complications (Table 3). Compared with OA, LA was associated with a lower rate of wound infections (LA, 8.8%; OA, 43.6%; P < 0.001). There were two patients in each group who developed an intra-abdominal abscess. One of those patients in the OA group underwent reoperation for drainage, the other three patients with the abdominal abscess were treated successfully with percutaneous drainage. Fistula was present in one patient in OA (2.6%) and postoperative hernia was present in one patient in LA (2.9%). There were no cases of postoperative bowel obstruction.

DISCUSSION

Although open appendectomy has been the gold standard for acute appendicitis because it is simple and effective, OA for perforated appendicitis has some drawbacks including wound infection and delayed recovery. Acute gangrenous and perforating appendicitis are associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications and have been considered a relative contraindication of LA.13,14 Nevertheless, some recent studies have challenged this concept, retrospectively, comparing surgical outcomes of LA for complicated appendicitis.12,16,19–21 These results suggest that LA for perforated appendicitis is safe and could offer patients faster recovery with less risk of infectious complications. Our study showed consistent results; compared with OA, LA was associated with less analgesic use, earlier oral intake restart, shorter median hospital stay, and lower rate of wound infections, while the operating time and the rate of intra-abdominal abscess were comparable between the two groups.

Unfortunately, in the previous publications concerning LA for complicated appendicitis, an adequate control group was not used. The LA group was retrospectively compared with OA performed during the same period. The present study is also a non-randomized analysis based on a retrospective review of the patient records. Indeed, the possibility cannot be excluded that the differences in antibiotics, analgesics, or surgeons as well as their enthusiasm for LA may affect some outcome measures, leading to significant bias. However, this is a single-institutional study in which the two groups of LA and OA were strictly divided by a period of relatively short duration (3 years each), possibly minimizing the heterogeneity of measured variables. Furthermore, the magnitude of the differences was large and prominent (LA factors are less than half as much as OA). The reduced rate of wound infections may contribute to the shortened hospital stay of the LA group, because most of the patients were not discharged from the hospital until the infected wound was completely cured.

In our study, LA markedly improved the postoperative wound infection rate. This may be because we removed the perforated appendix through an endoscopic bag, avoiding direct contact with the trocar wounds. The infected fluid was aspirated thoroughly in the laparoscopic approach. On the other hand, in OA, it was difficult to prevent the abdominal wall from being in contact with both the perforated appendix and infected fluid. Traditionally, surgical incisions have not been managed with primary closure but have been left open in complicated appendicitis. Thus, the possibility cannot be excluded that our closed wound technique may have contributed to the higher infection rate observed in OA. However, some relevant recent studies employing a meta-analyses reported that primary closure does not increase the risk of wound infection after operation for complicated appendicitis.22,23 The best management of these incisions still remains controversial.

The rate of developing a postoperative intra-abdominal abscess in our series of LA (5.9%) was similar to OA, but seems to be lower than that described previously (14%–26%).14,19 Furthermore, we did not convert any case of LA to OA, whereas a high conversion rate of LA for perforated appendicitis has been reported. Although a definitive answer as to how theses improvements were achieved is not readily available, advanced laparoscopic tools (e.g., flexible laparoscope or powerful suction/irrigation system) and improved skills of the surgeons may contribute to the better surgical outcomes. We think the flexible scope is a powerful tool for this laparoscopic surgery, which enabled us to visualize the retrocolic space beyond the enlarged intestine.

In the present series, laparoscopic appendectomies for complicated appendicitis were successfully accomplished with the conversion rate being zero. However, there are cases where laparoscopic appendectomy is hampered by the severe disease state. Recently we encountered some tough cases of abscess formation due to appendicitis. We performed “laparoscopic drainage” without appendectomy in these cases, because it was difficult to find and remove the inflamed appendix by the laparoscopic approach. One of the patients underwent interval appendectomy. The “laparoscopic drainage” (with or without interval appendectomy) can optionally be used in such a situation, which may contribute to lowering the conversion rate of complicated appendicitis.

Many prospective randomized studies for uncomplicated appendicitis have shown a longer operating time of LA. This is one of the reasons why LA for uncomplicated appendicitis has not been widely accepted. In contrast, in the present study the operating time of LA for perforated appendicitis was comparable to that of OA. This result is consistent with the previous reports for perforated appendicitis.18,19 Thus, one of the major disadvantages of LA is likely to be diminished, when the laparoscopic approach is applied to complicated appendicitis.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that LA for perforated appendicitis can be performed safely with a low incidence of infectious complications, possibly offering patients faster recovery than OA treated by a closed wound technique. Laparoscopic appendectomy may potentially have more prominent clinical advantages over conventional surgery, when compared with the impact of LA on uncomplicated appendicitis.

References

Hansen JB, Smithers BM, Schache D, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: prospective randomized trial. World J Surg 1996;20:17–21

Chung RS, Rowland DY, Li P, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of laparoscopic versus conventional appendectomy. Am J Surg 1999;177:250–256

Garbutt JM, Soper NJ, Shannon WD, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic and open appendectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1999;9:17–26

Golub R, Siddiqui F, Pohl D. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a metaanalysis. J Am Coll Surg 1998;186:545–553

Temple LK, Litwin DE, McLeod RS. A meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in patients suspected of having acute appendicitis. Can J Surg 1999;42:377–383

Sauerland S, Lefering R, Holthausen U, et al. Laparoscopic vs conventional appendectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 1998;383:289–295

Milewczyk M, Michalik M, Ciesielski M. A prospective, randomized, unicenter study comparing laparoscopic and open treatments of acute appendicitis. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1023–1028

Apelgren KN, Molnar RG, Kisala JM. Laparoscopic is not better than open appendectomy. Am Surg 1995;61:240–243

Mutter D, Vix M, Bui A, et al. Laparoscopy not recommended for routine appendectomy in men: results of a prospective randomized study. Surgery 1996;120:71–74

Katkhouda N, Mason RJ, Towfigh S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Ann Surg 2005;242:439–450

Moberg AC, Berndsen F, Palmquist I, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy for confirmed appendicitis. Br J Surg 2005;92:298–304

Guller U, Hervey S, Purves H, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: outcomes comparison based on a large administrative database. Ann Surg 2004;239:43–52

Bonanni F, Reed J, Hartzell G, et al. Laparoscopic versus conventional appendectomy. J Am Coll Surg 1994;179:273–278

Frazee RC, Bohannon WT. Laparoscopic appendectomy for complicated appendicitis. Arch Surg 1996;131:509–513

Johnson AB, Peetz ME. Laparoscopic appendectomy is an acceptable alternative for the treatment of perforated appendicitis. Surg Endosc 1998;12:940–943

Khalili TM, Hiatt JR, Savar A, et al. Perforated appendicitis is not a contraindication to laparoscopy. Am Surg 1999;65:965–967

Klingler A, Henle KP, Beller S, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy dose not change the incidence of postoperative infectious complications. Am J Surg 1998;175:232–235

Piskun G, Kozik D, Rajpal S, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic, open, and converted appendectomy for perforated appendicitis. Surg Endosc 2001;15:660–662

So JB, Chiong EC, Chiong E, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis. World J Surg 2002;26:1485–1488

Senapathi PS, Bhattacharya D, Ammori BJ. Early laparoscopic appendectomy for appendicular mass. Surg Endosc 2002;16:1783–1785

Mancini GJ, Mancini ML, Nelson HS Jr, et al. Efficacy of laparoscopic appendectomy in appendicitis with peritonitis. Am Surg 2005;71:1–5

Rucinski J, Fabian T, Panagopoulos G, et al. Gangrenous and perforated appendicitis: a meta-analytic study of 2532 patients indicates that the incision should be closed primarily. Surgery 2000;127:136–41

Henry MC, Moss RL. Primary versus delayed wound closure in complicated appendicitis: an international systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int 2005;21:625–630

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fukami, Y., Hasegawa, H., Sakamoto, E. et al. Value of Laparoscopic Appendectomy in Perforated Appendicitis. World J. Surg. 31, 93–97 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-006-0065-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-006-0065-x