Abstract

Objective

The objective was to examine the relationship between pre-, peri-, and postoperative specialized nutritional support with immune-modulating nutrients and postoperative morbidity in patients undergoing elective surgery.

Methods

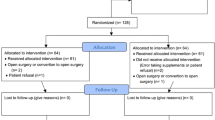

Studies were identified by searching MEDLINE, review article bibliographies, and abstracts and proceedings of scientific meetings. All randomized clinical trials in which patients were supplemented by the IMPACT formula before and/or after elective surgery and the clinical outcomes reported were included in the meta-analysis. Seventeen studies (n = 2,305), 14 published (n = 2,102), and 3 unpublished (n = 203), fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Ten studies (n = 1,392) examined the efficacy of pre- or perioperative IMPACT supplementation in patients undergoing elective surgery, whereas 7 (n = 913) assessed postoperative efficacy. Fourteen of the studies (n = 2,083) involved gastrointestinal (GI) surgical patients. Postoperative complications, mortality, and length of stay in hospital (LOS) were major outcomes of interest.

Results

IMPACT supplementation, in general, was associated with significant (39%–61%) reductions in postoperative infectious complications and a significant decrease in LOS in hospital by an average of 2 days. The greatest improvement in postoperative outcomes was observed in patients receiving specialized nutrition support as part of their preoperative treatment. In GI surgical patients, anastomotic leaks were 46% less prevalent when IMPACT supplementation was part of the preoperative treatment.

Conclusion

This study identifies a dosage (0.5–1 l/day) and duration (supplementation for 5–7 days before surgery) of IMPACT that contributes to improved outcomes of morbidity in elective surgery patients, particularly those undergoing GI surgical procedures. The cost effectiveness of such practice is supported by recent health economic analysis. Findings suggest preoperative IMPACT use for the prophylaxis of postoperative complications in elective surgical patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Immune suppression is a direct consequence of invasive procedures and as a result, surgical patients are at a high risk of infection. For example, 55% of patients will acquire infection following major cardiovascular surgery.1 Postsurgical complications including infections burden the health care system, slowing recovery, extending hospital stays, and increasing hospital expenses. A recent focus in medical practice is the proactive management of infection. The approach involves both pre- and postoperative treatments and has been shown to effectively reduce complications and decrease the overall cost of care. The provision of specialized nutrition support is one component of the proactive approach to infection control.

The specialized nutritional products currently available contain a blend of nutrients with immune-modulating potential including the amino acids arginine and glutamine, omega-3 fatty acids, and nucleotides/RNA. As four systematic reviews recently identified,2–5 specialized nutritional support is of particular benefit to hospitalized patients undergoing surgical procedures. Hospital-acquired infections and length of stay (LOS) in both the ICU and hospital were significantly decreased with the provision of specialized nutrition support. However, the former systematic reviews group various types of enteral products together despite considerable differences in the quality and quantity of immune-modulating nutrients.6

Considerable evidence supports that IMPACT specialized nutrition support (Novartis Consumer Health, Nyon, Switzerland) positively influences inflammatory, metabolic, and immune responses to major surgery.7–12 Of the various nutrients suggested to offer immune-modulating benefits, IMPACT contains a consistent mixture of arginine, omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil, and nucleotides in the form of RNA. Nucleotides are important during immunological challenge to support the development and activation of specialized immune cells.13 Arginine, the precursor of nitric oxide, is an amino acid that becomes conditionally essential during trauma and sepsis. Following surgery, arginine improves wound healing and protects against infection and ischemia–reperfusion tissue injury by restoring macrophage function and lymphocyte responsiveness.14–17 Omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil alter the phospholipid content of the cell membrane and shift the balance of leukotriene and prostaglandin production to less inflammatory and less immunosuppressive mediators.17–20 Furthermore, recent attention has been focused on the synergistic interaction of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil and arginine to modulate immune function after surgery.21

The aim of this review was to compare the effect of IMPACT specialized nutritional support initiated before and/or after elective surgery with that of standard postoperative nutritional support on postoperative morbidity outcomes. Based on recent evidence the hypothesis was formulated that specialized nutritional support may be considered a form of prophylaxis against postoperative morbidity. The present meta-analysis eliminates formula heterogeneity by exclusively analyzing studies using IMPACT specialized nutritional support. Furthermore, to improve upon previous systematic reviews, this analysis evaluates clinical outcomes associated with the initiation and duration of specialized nutrition support; and it identifies the various types of infectious comorbidities for surgical patients and gastrointestinal (GI) surgical patients in detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Identification

An electronic search for relevant articles was performed using the MEDLINE database. The keywords “enteral nutrition,” “surgical patients,” “arginine,” “fish oil,” “omega-3 fatty acids,” “nucleotides,” “glutamine,” “immunonutri*,” “preoperative,” “perioperative,” and “postoperative” were targeted. The search was limited to human clinical trials published between January 1985 and December 2003. In addition, reference lists of reviews and original articles were searched manually, and investigators identified by the manufacturer of IMPACT were contacted for unpublished data.

Study Selection Criteria

The following criteria were used to select studies for this review:

-

1.

Study type: randomized clinical trial

-

2.

Type of participants: surgical patients undergoing major elective operations

-

3.

Type of intervention: enteral nutrition and/or oral supplementation with IMPACT before and/or after surgery

-

4.

Type of outcome measures: defined postoperative infectious complications, mortality, length of hospital stay, and cost of in-hospital care

-

5.

Publication languages: English, German, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Japanese, and Chinese

To comply with the gold standard for systematic reviews,22 our analysis included all studies published in English and non-English literature as well as unpublished trials. Furthermore, to select studies with the highest validity in terms of a relative treatment effect, we included only randomized clinical trials.4,23 Studies reporting only nutritional or immunological outcomes were excluded, and clinical outcome was considered the primary outcome measure. Authors of multiple studies were contacted to obtain supplemental information not included in published articles and to avoid the use of duplicate data.

A methodological review was conducted by two investigators to assess study quality as defined by the scoring system described by Jadad.24

Primary Statistical Analysis

Primary outcomes of interest were the number of patients with one or more postoperative-acquired infection(s), the LOS in hospital, and hospital mortality. Individual studies defined and described the occurrence of infectious complications including wound infection, intra-abdominal abscess, pneumonia, urinary tract infection (UTI), and sepsis. Infection rates and the frequently encountered noninfectious surgical complication, anastomotic leak, were evaluated as secondary outcomes.

Statistical analyses utilized Comprehensive META ANALYSIS software, version 2.2.021, June 20, 2005 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA [http://www.Meta-Analysis. com]). Intent-to-treat analysis used summary data from published and unpublished studies. The most inclusive category was used when individual study results were not reported as intent-to-treat. Infection was treated as a binary variable. Results of the meta-analysis are expressed in terms of relative risk (RR) for the treatment group vs. the control group, such that an RR < 1 favors the treatment group and an RR > 1 favors the control group. Combined data from all 17 studies were used to estimate an overall RR and associated 95% confidence interval (CI). The Mantel-Haenszel method was used to test the significance of treatment effect25 and a random effects model estimated the overall RR.26 For LOS analysis, effect size (ES) was used to describe the standardized difference between means from treatment and control. Hedges method was used to estimate the individual ES and pooled ES between two treatments.27 The pooled simple difference between 2 group means is reported to provide the estimate of treatment effect in days. Only statistically significant ESs are analyzed in this manner. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analysis

Subgroup analyses were carried out for IMPACT supplementation during the presurgical (preoperative) or postsurgical (postoperative) period, or both (perioperative). Strength was assessed by comparing our findings with those achieved after analyses were confined to published studies or those associated with GI surgery.

RESULTS

Trials Identified

Search methods identified 58 citations and 4 unpublished randomized clinical trials that supplemented with IMPACT specialized nutritional support. Abstracts were analyzed with regard to the defined selection criteria. Studies found to meet inclusion criteria and those lacking sufficient data in the abstract were reevaluated using the full-text publication. Protocols or draft manuscripts were analyzed when data from trials were unpublished. Following full-text evaluation, 18 studies in total, 14 published 1,7,28–31–39 and 4 unpublished (Berne, Amsterdam, Sydney, and Open), met all the inclusion criteria. The test diet of all 18 studies had equal proportions of the immune modulating nutrients arginine, omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil, and nucleotides.

Eighteen out of 58 Published Studies Met Inclusion Criteria

Published studies were excluded for the following reasons: clinical outcome was not an endpoint in 15, the study was not randomized in 1, only a single immune modulating nutrient was evaluated in 5, the specialized nutritional formula was not IMPACT in 1, and surgical patients were not analyzed individually within the study population in 16. In addition, patient populations from 6 publications were compiled and included in subsequent publications to justify their exclusion from analyses. Of the 4 unpublished studies identified, the principal investigators provided adequate data for analysis of 3, including clinical outcome results (for each), study protocols (for 2), and a draft manuscript (for 1). The fourth study, although complete, was excluded because the data bank was not yet closed due to unresolved inconsistencies (Open). Table 1 details the characteristics of the 17 trials, comprising 2,305 patients, included in the analyses. Studies were generally of acceptable quality, 10 with a methodological score of 3 or above were considered moderate to high quality and 7 with a score of less than 3 were rated low quality.24

Descriptions of the Unpublished Trials Used in Analyses Follow

A prospective trial carried out in Switzerland (Berne) included 29 patients, split into 2 groups, who underwent major elective surgery for GI and/or pancreatic cancer. As detailed in Table 1, preoperative supplementation of IMPACT was the experimental variable. Both groups received IMPACT postoperatively. A separate trial of double-blind design was carried out in the Netherlands (Amsterdam) in a group of cardiac patients identified as “high risk” and undergoing cardio-pulmonary bypass according to a previously described protocol.1 Patients, 48 in total, were randomized into 2 groups, differing in supplementation of IMPACT nutrition support prior to surgery (Table 1). Patients received no enteral feeding following surgery. The third study of double-blind design originated in Australia (Sydney), and followed 126 patients undergoing major surgery for colorectal cancer. Patients randomly received either perioperative IMPACT or an isocaloric, isonitrogenous diet, and outcomes were evaluated (Table 1).

Surgical and Nutritional Interventions

All trials included patients undergoing major elective surgery. Fourteen studies described patients with GI malignancy; patients underwent upper GI surgery in 8 studies, lower GI surgery in 2, and upper or lower GI surgery in 4. Two studies included patients undergoing bypass and valve replacement surgery, and 1 included patients undergoing surgery for head or neck malignancy.

Ten studies, 7 published1,28–30,37–39 and 3 unpublished (Amsterdam, Sydney, and Berne), supplemented with IMPACT before surgery in efficacy trials of preoperative or perioperative specialized nutrition support. A variety of study designs were used to describe the efficacy of preoperative IMPACT supplementation. In 3 studies1,28 (Amsterdam), treatment was exclusively preoperative and IMPACT was compared with a standard formula that was isonitrogenous and isocaloric. A set of studies provided consistent postoperative support with IMPACT (Berne), a standard formula,30 or intravenous (i.v.) electrolytes (5% glucose),29 and compared preoperative supplementation with IMPACT versus no nutrition support.

A set of studies investigated the efficacy of perioperative IMPACT specialized nutritional support. Patients in the treatment group were supplemented with IMPACT both pre- and postoperatively. For comparison, patients in the control group received either an isocaloric, isonitrogenous formula30,37,39 (Sydney), a standard formula,38 or no nutritional support,28 preoperatively. The control group from another study28 received no nutritional support during both the pre- and postoperative treatment periods.

Seven studies investigated the immune-modulating effect of postoperative IMPACT supplementation,7,31–36 and 5 initiated patient feedings within 24 hours of surgery.7,31,33–35 Among the 7 postoperative studies, 1 compared IMPACT specialized nutrition with both a standard enteral formula and a low calorie, low fat i.v. solution.32 Another evaluated specialized nutritional support against isocaloric, isonitrogenous enteral and parenteral support.35 In summary, 6 of the postoperative efficacy trials compared IMPACT with a control enteral feed7,31–32,34,36 and 3 evaluated IMPACT against an i.v. solution or feed.32,34,35

Effect of IMPACT on Cost, Infectious Complication Rates, LOS in Hospital, and Mortality

Cost data were available from only two studies8,37 and were not analyzed further. Sixteen studies (out of 50) reported postoperative infectious complications as shown in Tables 2–4. The aggregated results of these studies demonstrate that the use of IMPACT was associated with significantly fewer postoperative infectious complications (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.42–0.58, P < 0.0001) and the test for heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.95; results not shown).

Sixteen of the 17 studies reported LOS in hospital (Tables 2–4). Mean and SD data were available for all but one study.25 Overall, patients receiving IMPACT had a significantly shorter LOS in hospital (ES (−)0.66, 95% CI (−)0.86–(−)0.45, P < 0.0001) and the test for heterogeneity was significant (P < 0.0001; results not shown). The pooled difference between the group means measured a reduction in LOS in hospital of 3.1 days (95% CI (−)3.9–(−)2.3 days) with IMPACT supplementation (results not shown).

Mortality was low in the patient population. Analysis of aggregate data did not detect an improvement in mortality rates with IMPACT supplementation (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.39–1.31, P = 0.28) and the test for heterogeneity was not significant (P = 0.98; results not shown).

Effect of IMPACT on Postoperative Morbidity

Meta-analysis of postoperative morbidity reported in these 17 trials indicated that IMPACT supplementation was associated with significantly fewer outcomes of morbidity (Table 5), including wound infections (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.46–0.87, P = 0.005), abdominal abscesses (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.29–0.72, P = 0.001), pneumonia (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.39–0.71, P < 0.0001), UTIs (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.32–0.87, P = 0.011), and anastomotic leaks (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.37–0.83, P = 0.004), whereas the number of septic episodes was also reduced by more than 40%, but not statistically significantly (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.30–1.03, P = 0.060) (Table 6). The test for heterogeneity for all parameters was not significant (P = 0.81–0.99).

Subgroup Analysis

The effect of the pre-, peri-, and postoperative application of IMPACT was examined. Compared with their control counterparts, the rate of infectious complications was significantly lower in patients receiving IMPACT preoperatively (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.30–0.59, P < 0.0001) and perioperatively (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.39–0.62, P < 0.0001), as well as with postoperative supplementation alone (IMPACT vs. enteral or i.v. control) (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.75, P = 0.0001; Tables 2–4). Separate evaluation of the postoperative use of IMPACT against a standard enteral formula or i.v. solution (Table 4) showed that infectious complications were significantly reduced with IMPACT supplementation in both groups (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.39–0.82, P = 0.003 in standard enteral controls; RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.31–0.90, P = 0.02 in i.v. controls).

Grouping studies by their initiation of IMPACT treatment identified that preoperative supplementation (ES (−)0.71, 95% CI (−)1.14–(−)0.28, P = 0.001) and perioperative supplementation (ES (−)0.48, 95% CI (−)0.68–(−)0.28, P < 0.0001) were associated with significantly shorter LOS in hospital (Tables 2, 3). The pooled difference between group means was (−)3.4 days, 95% CI (−)5.6–(−)1.2 days preoperatively and (−)2.4 days, 95% CI (−)3.1–(−)1.7 days perioperatively (Tables 2, 3). In comparison, postoperative supplementation of IMPACT was also associated with a significant decrease in LOS in hospital (ES (−)0.73, 95% CI (−)1.18–(−)0.29, P = 0.001), a pooled difference of (−)3.5 days, 95% CI (−)5.1–(−)1.9 days. Comparison of postoperative IMPACT supplementation with a standard enteral formula showed that LOS in hospital again decreased significantly (ES (−)0.84, 95% CI (−)1.43–(−)0.25, P = 0.006), whereas postoperative IMPACT supplementation vs. i.v. control showed a decrease that did not reach statistical significance (ES (−)0.47, 95% CI (−)1.1–0.16, P = 0.145; Table 4).

There was no significant difference in mortality for the 3 subgroups, preoperative (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.23–2.35, P = 0.51), perioperative (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.14–1.61, P = 0.23), or postoperative (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.36–2.10, P = 0.75) IMPACT supplementation (Tables 2–4).

As shown in Table 7, when specific postoperative complications were analyzed in GI surgical patients preoperative IMPACT supplementation resulted in fewer abdominal abscesses (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.16–1.19, P = 0.107), fewer wound infections (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.29–1.07, P = 0.077), significantly less pneumonia (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.18–0.83, P = 0.015), fewer UTIs (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.28–1.47, P = 0.142), fewer episodes of sepsis (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.05–1.71, P = 0.169), and fewer anastomotic leaks (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.24–1.05, P = 0.069). Perioperative application of IMPACT was associated with significantly fewer abdominal abscesses (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.21–0.91, P = 0.027) and wound infections (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.38–0.96, P = 0.033), less pneumonia (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.34–0.87, P = 0.011), fewer UTIs (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.23–1.19, P = 0.122) and episodes of sepsis (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.22–1.27, P = 0.153), as well as significantly fewer anastomotic leaks (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28–0.95, P = 0.034). The test for heterogeneity for all parameters was not significant (P = 0.58–0.99). Significantly fewer abdominal abscesses (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.24–0.98, P = 0.044), but no significant improvement in the other types of postoperative complications was found in the subset of GI patients supplemented postoperatively (Table 7).

Sensitivity Analysis

The status of publication did not affect the overall outcome. When limiting analyses to the 14 published studies, IMPACT supplementation continued to significantly reduce infectious complications (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.42–0.60, P < 0.0001), and LOS in hospital (ES (−)0.63, 95% CI (−)0.83–(−)0.43, P < 0.0001), resulting in a pooled difference between group means of (−)3.0 days, 95% CI (−)3.7–(−)2.3 days (data not shown). Again, no significant effect was detected with regard to mortality (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.40–1.42, P = 0.37) in the patient population (data not shown). When measures of postoperative morbidity were analyzed in the published studies alone, IMPACT supplementation remained associated with significantly fewer abdominal abscesses (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.28–0.72, P = 0.001) and wound infections (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45–0.94, P = 0.021), less pneumonia (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.39–0.77, P = 0.001), and fewer anastomotic leaks (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.36–0.81, P = 0.002), whereas a reduction in UTIs (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.37–1.05, P = 0.076) was no longer statistically significant (Table 6). The test for heterogeneity for all parameters was not significant (P = 0.84–0.99).

When analyses were limited to studies of upper and lower GI procedures and the results from 3 studies were excluded (1,37, and Amsterdam), the outcomes of morbidity, LOS in hospital, and mortality did not change. IMPACT groups had significantly reduced infectious complications (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.42–0.60, P < 0.0001) and LOS in hospital (ES (−)0.72, 95% CI (−)0.94–(−)0.50, P < 0.0001), resulting in a pooled difference between group means of (−)3.2 days, 95% CI (−)4.1–(−)2.4 days (data not shown). No significant effect on mortality was determined in the patient population (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.38–1.37, P = 0.32; data not shown). Analyses (Table 6) identified comparable reductions in the various outcomes of postoperative morbidity, and complications were significantly avoided, with the exception of septic episodes, in the IMPACT group (P = 0.001–0.013).

Applying above the sensitivity analyses, significant reductions in infectious complications and LOS in hospital were observed under pre- and perioperative IMPACT supplementation (results not shown), whereas significance was lost in the postoperative group.

When limiting analyses to 10 studies of moderate to high quality (Jadad score ≥3), IMPACT supplementation continued to significantly reduce infectious complications (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.41–0.60, P < 0.0001), and LOS in hospital (ES (−)0.61, 95% CI (−)0.79–(−)0.43, P < 0.0001), resulting in a pooled difference between group means of (−)2.6 days, 95% CI (−)3.1–(−)2.1 days (data not shown). Again, no significant effect was detected with regard to mortality (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.32–1.62, P = 0.37) in the patient population (data not shown). When measures of postoperative morbidity were analyzed in the moderate to high quality studies alone, IMPACT supplementation remained associated with significantly fewer abdominal abscesses (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.22–0.73, P = 0.003) and wound infections (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.90, P = 0.015), less pneumonia (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.38–0.76, P = 0.0001), and fewer anastomotic leaks (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.35–0.81, P = 0.003; Table 6). Identical results were found when limiting analyses to the 9 studies that were evaluated on an “intent-to-treat” basis. IMPACT supplementation showed significantly reduced infectious complications (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.39–0.59, P < 0.0001) and LOS in hospital (ES (−)0.76, 95% CI (−)1.05–(−)0.47, P < 0.0001), resulting in a pooled difference between group means of (−)3.4 days, 95% CI (−)4.6–(−)2.2 days (data not shown) and significantly reduced abdominal abscesses, wound infections, pneumonia, and anastomotic leaks (Table 6). Restricting the analyses to 8 blinded studies yielded comparable results with the exception that the reduction in abdominal abscesses was no longer statistically significant (Table 6). Limiting the analyses to the 10 studies that used isonitrogenous, isocaloric control feed also yielded comparable results with the exception that the reduction in UTIs and abdominal abscesses was no longer statistically significant (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

As a result of medical advances, surgical procedures are generally less invasive. Paradoxically, infection rates associated with hospital stays are increasing. Furthermore, with extended hospital stays, the risk of infection increases. The surgical patient is at a particularly high risk of infection when visceral organ beds are involved. Immunity is compromised due to the stress of tissue ischemia and reperfusion combined with blood hemorrhage and transfusion. Furthermore, the GI surgical patient is at risk of the common and costly postoperative complication of elective surgery, the anastomotic leak.

The present meta-analysis describes the efficacy of IMPACT specialized nutritional support in a patient population at a high risk of postoperative complications. One consistent formulation was used in each of the 17 studies evaluated, providing homogeneity across trials in the quality and relative quantity of immune modulating nutrients administered. No adverse effects have been observed in the arginine, omega-3 fatty acid and nucleotide (IMPACT specialized nutrition) supplemented patient groups. The preoperative supplementation period lasted 5–7 days and delivered 0.5–1 l of IMPACT specialized nutritional support per day, on average. In 10 of the 17 trials, IMPACT was compared with an isocaloric, isonitrogenous control product; therefore, the observed differences in clinical outcome cannot be attributed to the calorie or nitrogen content of the experimental formula. Our analyses revealed a significant relative reduction in the risk of all described postoperative infections with the supplementation of IMPACT. Sensitivity analyses demonstrated that, under supplementation with IMPACT, the results regarding the significant reduction in infectious complications per se, in LOS in hospital by more than 2 days, and in abdominal abscesses, wound infections, and pneumonia were very robust.

The analyses provide the first comparison of the pre-, peri-, and postoperative application of IMPACT specialized nutritional support. Building and expanding upon previous meta-analyses2–5, which demonstrated significant immune-related treatment effects, our meta-analysis detected significant reductions in specific types of postoperative infections. Pneumonia and UTIs were reduced significantly (∼50%) in all studies, whereas wound infections were down ∼35% and ∼40% in all and GI-specific studies respectively. The length of hospital stay after surgery was reduced in 15 of the 17 studies analyzed, contributing to an overall reduction in LOS in hospital of more than 2 days. Such findings parallel a recent report that describes the health-economic advantage of using specialized nutrition for 5 days prior to surgery in GI patients.40

The beneficial effects of IMPACT on clinical outcomes in elective surgery patients were associated with the initiation of supplementation. Significant reductions in infectious complications and LOS in hospital were observed in all groups independent of whether IMPACT specialized nutrition support was given pre-, peri-, or postoperatively. Our analysis of postoperative outcomes in surgical patients suggests that the ingredient formulation of IMPACT appears to provide therapeutic advantages beyond the standard nutritional support. Best outcomes were observed when IMPACT was supplemented during the preoperative period, generally 0.5–1.0 l/day for 5–7 days before surgery. Supplementation significantly lowered complication rates for wound infections, pneumonia, UTIs, and abdominal abscesses in elective surgical patients, as well anastomotic leaks in GI surgical patients. Since a similar number of studies were evaluated for all three modes of IMPACT supplementation, our results accurately reflect the reduced efficacy of postoperative specialized nutritional support alone, however, better than standard methods of support.

Of the 17 studies analyzed, 14 involved patients undergoing upper or lower GI surgery, offering a unique opportunity to characterize a clinically homogeneous patient population. Here, we saw the most substantial benefit of IMPACT supplementation, an approximately 60% reduction in the frequency of abdominal abscesses following GI surgery (Table 6). The incidence of anastomotic leaks, a major complication of GI surgery with considerable rates of morbidity and mortality (up to 30% mortality), and cost41,42, was significantly reduced (∼50%) with perioperative IMPACT supplementation (Table 7). Our analyses show that preoperative IMPACT specialized nutritional support is of substantial benefit, while early postoperative supplementation does not increase the risk of anastomotic leak as confirmed by subgroup analysis (Table 7). Improved oxygenation and perfusion of gut vasculature with IMPACT supplementation11,28 may be responsible for this clinical benefit. In fact, a significant correlation between decreased colon microperfusion and increased rate of dehiscence in rectal surgery has been reported.43 Our findings indicate that IMPACT provides therapeutic benefits beyond standard nutrition. Furthermore, our findings indicate that IMPACT promotes the healing of intestinal anastomoses performed during GI surgery, as we saw a consistent reduction in the incidence of anastomotic leaks with preoperative supplementation. Collectively, IMPACT supplementation appears warranted in surgical patients as part of the proactive approach to infection control. For the maximum benefit, patients should receive 0.5–1 l of IMPACT for 5–7 days before surgery. In cases in which full preoperative treatment is not possible, early postoperative support with IMPACT can improve postoperative outcomes beyond standard nutrition.

References

Tepaske R, te Velthuis H, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, et al. Effect of preoperative oral immune-enhancing nutritional supplement on patients at high risk of infection after cardiac surgery: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2001;358:696–701

Heys SD, Walker LG, Smith I, et al. Enteral nutrition supplementation with key nutrients in patients with critical illness and cancer. Ann Surg 1999;229:476–477

Beale RJ, Bryg DJ, Bihari DJ. Immunonutrition in the critically ill: a systematic review of clinical outcome. Crit Care Med 1999;27:2799–2805

Heyland DK, Novak F, Drover JW, et al. Should immunonutrition become routine in critically ill patients? A systematic review of the evidence. JAMA 2001;286:944–953

Montejo JC, Zarazaga A, Lopez-Martinez J, et al. Immunonutrition in the intensive care unit. A systematic review and consensus statement. Clin Nutr 2003;22:221–233

Wyncoll D, Beale R. Immunologically enhanced enteral nutrition: current status. Curr Opin Crit Care 2001;7:128–132

Daly JM, Lieberman MD, Goldfine J, et al. Enteral nutrition with supplemental arginine, RNA, and omega-3 fatty acids in patients after operation: immunologic, metabolic, and clinical outcome. Surgery 1992;112:327–338

Gianotti L, Braga M, Frei A, et al. Health care resources consumed to treat postoperative infections: cost savings by perioperative immunonutrition. Shock 2000;14:325–330

Kemen M, Senkal M, Homann HH, et al. Early postoperative enteral nutrition with arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and ribonucleic acid-supplemented diet versus placebo in cancer patients: an immunologic evaluation of IMPACT®. Crit Care Med 1995;23:652–659

Senkal M, Kemen M, Homann HH, et al. Modulation of postoperative immune response by enteral nutrition with a diet enriched with arginine, RNA, and omega-3 fatty acids in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer. Eur J Surg 1995;161:115–122

Braga M, Gianotti L, Gestari A, et al. Gut function, immune and inflammatory responses in patients fed perioperatively with supplemented formulas. Arch Surg 1996;131:1257–1265

Wachtler P, Hilger RA, König W, et al. Influence of a pre-operative enteral supplement on functional activities of peripheral leukocytes from patients with major surgery. Clin Nutr 1995;14:275–282

Kulkarni AD, Rudolph FB, Van Buren CT. The role of dietary sources of nucleotides in immune function: a review. J Nutr 1994;124:1442S–1446S

Kirk SJ, Hurson M, Regan MC, et al. Arginine stimulates wound healing and immune function in elderly human beings. Surgery 1993;114:155–160

Sato H, Zhao ZQ, McGee DS, et al. Supplemental L-arginine during cardioplegic arrest and reperfusion avoids regional postischemic injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;110:302–314

Jones SM, Thurman RG. L-arginine minimizes reperfusion injury in a low-flow, reflow model of liver perfusion. Hepatology 1996;24:163–168

Nonami Y. The role of nitric oxide in cardiac surgery. Surg Today 1997;27:583–592

O’Leary MJ, Coakley JH. Nutrition and immunonutrition. Br J Anaesth 1996;77:118–127

Meydani SN, Dinarello CA. Influence of dietary fatty acids on cytokine production and its clinical implications. Nutr Clin Pract 1993;8:65–72

Calder PC. Immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of n-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids. Braz J Med Biol Res 1998;31:467–490

Luiking YC, Poeze M, Dehong CH, et al. Sepsis: an arginine deficiency state? Crit Care Med 2004;32(10):2135–2145

Burdett S, Stewart LA, Tierny JF. Publication bias and meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2003;19:129–134

Heyland DK, MacDonald S, Keefe L, et al. Total parenteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1998;280:2013–2019

Jadad A. Random controlled trials. London: BMJ, 1998

Rothman KJ, Boice JD. Epidemiological analysis with a programmable calculator. Washington, DC, National Institutes of Health, 1979

Fleiss JL, Gross AJ. Meta-analysis in epidemiology, with special reference to studies of the association between exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and lung cancer. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:127–139

Hedges LV. Estimation of effect size from a series of independent experiments. Psychol Bull 1982;92:490–499

Braga M, Gianotti L, Vignali A, et al. Preoperative oral arginine and –3 fatty acid supplementation improves the immunometabolic host response and outcome after colorectal resection for cancer. Surgery 2002;132:805–814

Gianotti L, Braga M, Nespoli L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of preoperative oral supplementation with a specialized diet in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1783–1770

Braga M, Gianotti L, Nespoli L, et al. Nutritional approach in malnourished surgical patients: a prospective randomized study. Arch Surg 2002;137:174–180

Daly JM, Weintraub FN, Shou J, et al. Enteral nutrition during multimodality therapy in upper gastrointestinal cancer patients. Ann Surg 1995;221:327–338

Schilling J, Vranjes N, Fierz W, et al. Clinical outcome and immunology of postoperative arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and nucleotide-enriched enteral feeding: a randomized prospective comparison with standard enteral and low calorie/low fat i.v. solution. Nutrition 1996;12:423–429

Senkal M, Mumme A, Eickhoff U, et al. Early postoperative enteral immunonutrition: clinical outcome and cost-comparison analysis in surgical patients. Crit Care Med 1997;25:1489–1496

Heslin MJ, Latkany L, Leung D, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of early enteral feeding after resection of upper gastrointestinal malignancy. Ann Surg 1997;226:567–577

Gianotti L, Braga M, Vignali A, et al. Effect of route of delivery and formulation of postoperative nutritional support in patients undergoing major operations for malignant neoplasms. Arch Surg 1997;132:1222–1230

Jiang ZM. The role of immune enhanced enteral nutrition on plasma amino acid, gut permeability and clinical outcome in post-surgery patients. Acta Chin Acad Med Sci 2001;23:515–518

Senkal M, Zumtobel V, Bauer KH, et al. Outcome and cost-effectiveness of perioperative enteral immunonutrition in patients undergoing elective upper gastrointestinal tract surgery: a prospective randomized study. Arch Surg 1999;134:1309–1316

Snyderman CH, Kachman K, Molseed L, et al. Reduced postoperative infections with an immune-enhancing nutritional supplement. Laryngoscope 1999;109:915–921

Braga M, Gianotti L, Radaelli G, et al. Perioperative immunonutrition in patients undergoing cancer surgery: results of a randomized double-blind phase 3 trial. Arch Surg 1999;134:428–433

Braga M, Bianotti L. Preoperative immunonutrition: cost-benefit analysis. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2005;29(1):S57–S61

Wheeler JM, Gilbert JM. Controlled intraoperative water testing of left-sided colorectal anastomoses: are ileostomies avoidable? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1999;81:105–108

Strickland A, Brogan A, Krauss J, et al. Is the use of specialized nutritional formulations a cost-effective strategy? A national database evaluation. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2005;29(1):S81–S91

Vignali A, Gianotti L, Braga M, et al. Altered microperfusion at the rectal stump is predictive for rectal anastomotic leak. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:76–82

Acknowledgements

The hypothesis for this investigation was conceived at a workshop attended by leading practitioners from Asian Pacific and Latin American regions and co-chaired by Drs. Waitzberg and Saito. The authors gratefully acknowledge Novartis Medical Nutrition, Nyon Switzerland, for sponsoring the workshop, and Dr. Heinz Schneider of HealthEcon, Health Service Consultants, Basel, Switzerland, for organizing the event. We also thank Dr. T. Grunberger, Dr. R. Tepaske, and Dr. L. Krahenbuhl for supplying outcome data prior to their publication; A. Schmid for data accrual; and Dr. C. Galani for statistical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Waitzberg, D.L., Saito, H., Plank, L.D. et al. Postsurgical Infections are Reduced with Specialized Nutrition Support. World J. Surg. 30, 1592–1604 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0657-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0657-x