Abstract

Background

Granulomatous lobular mastitis is a rare chronic inflammatory disease of the breast. Clinical and radiological features may mimic breast carcinoma. Since this entity was first described, several clinical and pathologic features of the disease have been reported, but diagnostic features and treatment alternatives are still unclear. The purpose of this study is to evaluate diagnostic difficulties and discuss the outcome of surgical treatment in a series of 21 patients with granulomatous lobular mastitis.

Methods

A retrospective review of 21 patients with histologically confirmed granulomatous lobular mastitis treated in our center between January 1995 and May 2005 was analyzed to identify issues in the diagnosis and treatment of this rare condition.

Results

The most common presenting symptoms were a mass in the breast and pain. Four patients had no significant mammographic findings (MMG), but on ultrasound (US), 2 had irregular hypoechoic mass, and 2 hypoechoic nodular structures had abnormalities—one parenchymal distortion and 1 mass formation in 2 of these 4 patients’ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In recurrent cases, limited excision under local anesthesia was performed, as the clinical examination suggested carcinoma.

Conclusions

Although some findings on MMG and US are suggestive of benign breast disease, these modalities do not rule out malignancy. MRI may be helpful in patients who do not have significant pathology at MMG or US. Fine-needle aspiration cytology may be useful in some cases but diagnosis is potentially difficult because of its cytologic characteristics. Wide excision, particularly under general anesthesia, can be therapeutic as well as useful in providing an exact diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Granulomatous lobular mastitis (GLM) is a rare chronic inflammatory disease of the breast. Clinical and radiological features may mimic breast carcinoma.1 Most patients are young parous women and have previously used oral contraceptives. GLM is frequently associated with pregnancy and lactation.1–3 The lesions are usually unilateral and can occur in any quadrant of the breast but tends to save the subareolar region. Contralateral breast involvement is not usual.1,4 The etiology and pathogenesis of GLM is not clear, but localized immune response to local trauma, local irritants, or viruses are speculated. GLM is characterized pathologically by the presence of chronic granulomatous lobulitis in the absence of an obvious etiology.5,6 Use of corticosteroids and surgical excision of the lesions have been reported for the treatment of the GLM.7,8 There is no agreement about the most appropriate approach in these patients. The aim of this study was to review clinical and diagnostic features and discuss the result of surgical treatment in a series of 21 patients with GLM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twenty-one cases diagnosed histologically as GLM, identified from surgical and pathological records between January 1995 and May 2005, were reviewed retrospectively. These patients represented 1.6% of all patients who underwent surgery for breast diseases in our department during this period. Presentation, radiological and pathological results, treatment, and outcome were analyzed. Nineteen patients were examined with mammography (MMG), 21 had ultrasonography (US), and 6 had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In 2 patients, mammographic evaluation was not performed due to the young age of the patients and benign clinical impression. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy was performed in 9 patients. Definitive diagnosis was obtained from excisional biopsies. All slides were examined with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and special stains such as gram, Ziehl-Neelson, and periodic acid-Schiff.

RESULTS

Clinical Features

Clinical features of all patients with GLM are shown in Table 1. The mean age of affected women was 36.3 ± 11.4 (range 20–67) years. Most patients (90.5%) were of reproductive age. Common presenting symptoms were a mass in the breast (57.1%) and pain (33.3%). The masses were quite hard and measured clinically 1.5–8.5 cm (mean 3.8 cm) in size. In 4 patients, the overlying skin was inflamed. Nipple inversion was found in 2 patients. Axillary lymphadenopathy was established in 3 patients. Only 1 patient presented with a fistula. The left breast was involved in 13 cases (62%) and right in 8 (38%). Synchronous or metachronous involvement of the contralateral breast was not found.

Radiologic Evaluation

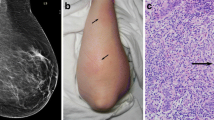

Imaging findings are summarized in Table 2. Mammographic examination showed an asymmetric density with no distinct margins in 9 patients and an ill-defined mass in 6 patients. In 4 cases, the parenchymal breast pattern was dense, and no abnormal findings were detected on MMG. Sonographic examination showed an irregular hypoechoic mass in 7 patients, hypoechoic nodular structures in 7, and focally decreased parenchymal echogenicity with acoustic shadowing in 5. US was normal in 2 patients. MRI was performed in 6 patients preoperatively and 1 postoperatively. MRI showed focal homogenous enhancing masses with irregular borders in 2 patients, parenchymal distortion in 3, and parenchymal asymmetry in 1. In one patient, MRI showed ring-like abscess formation 1 month after excision (Fig. 1). In 12 patients (57.1%), clinical and radiological findings before surgery suggested a malignant neoplasm. In 9 patients, benign breast diseases, such as periductal mastitis, intraductal papilloma, and fibroadenoma was considered.

Histopathologic Evaluation

FNA results were benign in 4 patients, malignant in 1, and inconclusive in 4 patients because of insufficient materials or nonspecific inflammatory findings. Frozen section analysis carried out in 4 patients revealed benign pathology. Mastitis was described as a granulomatous inflammatory response centered on breast lobules with the absence of a caseous necrosis and any specific organism (Fig. 2).

Treatment

Cellulitis and fistula formation was seen in 5 patients at presentation. They received oral ampicillin-sulbactam therapy for 10 days preoperatively. All patients received a single dose of ampicillin-sulbactam preoperatively and 10 days after surgery. Wide excision was performed in all patients except 4. Details of the surgical procedures for each patients is depicted in Table 1. Pathologic examination was carried out in each patient.

Follow-up

Median follow-up was 29 (range 3–73) months. Follow-up data were complete for 17 (80.9%) of the 21 patients. Recurrence developed in 2 (9.5%) patients. In the first patient, a mass lesion appeared in the same location of the breast 16 months after excision, and in the other, abscess and fistula formation developed only 1 month after excision. The first patient with recurrence was successfully treated by reexcision while the second patient was treated by oral steroid therapy followed by antibiotic therapy and abscess drainage because of widespread involvement. In the two recurrent cases, normal blood prolactin levels were found.

DISCUSSION

GLM a rare benign breast disease,1,2 was first described in 1972 by Kessler and Wolloch. Few articles exist in the literature, most of which are case reports and small series.7–10 Most patients are young parous women, but males may also be affected.1,2 Age at diagnosis is generally between 20 and 50 years; however, patients at 11 and 83 years were reported.4,11 GLM occurs commonly in recent pregnancy and lactation.2,3 In this study, mean patient age was 36.3 (range 20–67) years. All patients except 2 were in their reproductive period. Only 3 patients had previously used contraceptive pills, and 3 patients had lactated in the last 12 months.

The etiology of GLM is not clear. Many agents, such as local irritants, viruses, mycotic, and parasitic infections, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and alfa-1 antitrypsin deficiency have been considered, but an autoimmune reaction is favored.1,3–6,12 Also, similarity between GLM and autoimmune diseases such as granulomatous thyroiditis, granulomatous prostatitis, granulomatous orchitis, and response to steroid treatment fit in with the autoimmune hypothesis.5 However, this hypothesis has been challenged by some authors who have found no immunologic abnormalities in such patients. There is no sound scientific evidence for any of these etiologies. Serologic and bacterial tests are usually negative.13 No pathogenic microorganisms were detected in our series. Damage to the ductal epithelium produced by any of these etiological factors could permit luminal secretion to leak in to the lobular connective tissue, thereby causing a localized immune reaction with lymphocyte and macrophage migration.3 Blunt trauma has been reported as an etiology.11 The tendency toward the left breast was noticed in some of the other reported series.11,14,15 Recently, Bani-Hani et al. pointed out that the largest reported series of GLM come from developing countries. Because of this, they suggested that GLM might be the reflection of underdiagnosis of tuberculosis mastitis.16 The cytomorphologic pattern seen in tuberculous mastitis is indistinguishable from that seen in GLM. Since it is not always possible to detect acid-fast bacilli in histologic sections of tuberculous mastitis, accurate diagnosis can safely be made only when additional clinical data is present.

A breast mass is the most common presentation in GLM. Sometimes, the mass may penetrate the breast skin or the underlying pectoralis muscle. Nipple retraction, sinus formation, and axillary lymphadenopathy may be seen.1,3,12,17 These findings also suggest breast carcinoma. For this reason, the use of multiple assessments that contain clinical and cytologic examinations as well as imaging modalities are required for diagnostic accuracy. Asymmetric diffuse increased density of the fibroglandular tissue was the most frequent nonspecific mammographic finding in our study. This finding can be seen in normal breast or other types of diseases, including cancer. On the other hand, no clear mammographic abnormality was found in 4 patients. Corresponding US of these 4 patients showed various features: an irregular hypoechoic mass lesion in 2 cases, and in 2 cases, hypoechoic nodular structures as well. These are also the most common US findings for breast carcinoma. As a result, both MMG and US can be misleading. This reflects the importance of awareness of this entity by radiologists.

Recently, numerous studies were reported that described the use of MRI as a complementary diagnostic modality in breast imaging.4,12,18 GLM has a number of appearances on MRI. In our study, MRI showed focal homogenous enhancing masses with irregular borders in 2 patients, parenchymal distortion in 3, and parenchymal asymmetry in 1. There was no abnormal finding on MMG in 2 of these 6 patients. It is difficult to differentiate a granulomatous process from breast cancer with these MRI findings. According to our results, we think that the role of MRI in the characterization of inflammatory processes of the breast is nonspecific, but MRI is useful in patients who have no significant pathology on MMG or US. In the cases that have pathological findings on MMG or US, MRI is important because of its ability to demonstrate morphologic features of breast masses. MRI with measurement of time-signal intensity curves may support the findings of US an MMG in distinguishing benign inflammatory breast disorders from malignant ones. Additionally, some authors considered that MRI will be a promising imaging modality to evaluate extent and reduction of the lesions in time.12,18 We did not use MRI at postoperative follow-up, but in a patient who had recurrent disease, MRI showed ring-like abscess formations (Fig. 1).

Other causes of granulomatous lesions in the breast that require different treatments must be excluded. These include infective causes such as tuberculosis, brucellosis, parasitic infections such as filariasis, fungal infections such as actinomycosis, and systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and giant-cell arteritis.1,19–22 Foreign-body reaction, fat necrosis, and ductal ectasia must also be excluded.1,2,23

Since clinical and imaging diagnoses have often been difficult and inconclusive, histopathologic evaluation plays a crucial role for the diagnosis of GLM. Diagnosis can be challenging, and cytologic features can be difficult to distinguish from those of carcinoma and other granulomatous disease of the breast, such as specific infections (mycobacterium tuberculosis, fungus, parasites), duct ectasia, periductal mastitis, plasma-cell mastitis, sarcoidosis, and vasculitis.17,24 In this study, in 1 patient, FNA cytology revealed a few atypical epithelial groups with hyperchromatic nuclei. The cytologic diagnosis was class V, and breast carcinoma was highly suspected. Although the preoperative findings suggested breast carcinoma, it was histopathologically diagnosed as GLM after lesion excision. Due to the misleading findings, sometimes unnecessary mastectomies have been reported in the literature.3,11 It seems that the diagnosis of GLM is a histologic diagnosis that cannot safely be made on cytologic grounds alone.

Experience with optimal treatment of granulomatous mastitis is still limited. Treatment alternatives have been described in very few articles.4,7,8 There is insufficient data about antibiotherapy use on GLM. Most GLM lesions look like malignant tumors, which are generally sterile, and therefore antibiotherapy administration does not take place in most patients preoperatively. GLM is sometimes complicated by abscess formation, fistulae, or chronic suppuration. Mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections may be seen after recurrence. Antibiotics should be used. In 1 patient, corticosteroid therapy was given after antibiotherapy due to infected recurrent disease.

Our experience shows that wide surgical excision was associated with a lower complication rate than limited excision. Surgical excision can be therapeutic as well as useful in providing exact diagnosis. After excision, if there is no delayed wound healing, infection, or recurrence, further therapy is not needed. In the literature, different recurrence rates (range, 5.5%–50%) are reported after excision.4,12 In this study, recurrence developed in 2 (9.5%) patients. For those 2 patients with recurrences, limited excision was performed under local anesthesia, as the preoperative diagnosis was considered malignant. General anesthesia is preferred, as it allows wide excisions or quadrantectomy when differential diagnosis between GLM and malignancy cannot be made. Reexcision was performed widely in a patient with recurrence, and during the follow-up period, she was disease free. However reexcision is sometimes not possible, particularly for patients with advanced invasion. Steroid treatment should be administered after excision for complicated and resistant cases, and it may be also wise to give steroids to initially unresectable lesions before surgery. Steroid treatment decreases lesion dimension and augments complete healing after excision. Satisfactory results have been reported with high doses of prednisone, but there has been reluctance for side effects, such as glucose intolerance and cushingoid features.9,25 Our policy is to use steroids only in recurrent and complicated patients. We should not forget that steroids exacerbate infectious disease of the breast, so exclusion of an infectious etiology is essential before the treatment. Some reports suggest that high doses of corticosteroids should be maintained until complete resolution, but this treatment is often difficult because of the side effects.25,26,27 Despite these aggressive approaches, Lai et al. suggested that expectant, conservative management with close surveillance might be the treatment modality of choice because of the self-limiting nature of GLM.11 However, conservative management alone is a difficult decision to make because of diagnostic confusion, and may even require excision.

CONCLUSIONS

GLM is an entity in which preoperative diagnosis is difficult and treatment is controversial. Routine radiological examinations cannot lead us to accurate diagnosis, but some features are suggestive for this benign breast disease. Although FNA cytology is a useful diagnostic tool, it cannot always supply definite result. Therefore, radiological—including MMG, US, and MRI—and cytological correlations are also provided preoperatively. Wide surgical excision, particularly under general anesthesia, is often therapeutic. Steroid therapy may be an adjuvant for optimal treatment.

References

Erhan Y, Veral A, Kara E, et al. A clinicopathologic study of a rare clinical entity mimicking breast carcinoma: idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Breast 2000;9:52–56

Donn W, Rebbeck P, Wilson C, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. A report of three cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994;118:822–825

Imoto S, Kitaya T, Kodama T, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1997;27:274–277

Asoglu O, Ozmen V, Karanlik H, et al. Feasibility of surgical management in patients with granulomatous mastitis. Breast J 2005;11:108–114

Kessler E, Wolloch Y. Granulomatous mastitis: a lesion clinically simulating carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1972;58:642–646

Cohen C. Granulomatous mastitis. A review of 5 cases. S Afr Med J 1977;52:14–16

Dixon JM, Chetty U. Diagnosis and treatment of granulomatous mastitis. Br J Surg 1995;82:1143–1144

Moore GE. Diagnosis and treatment of granulomatous mastitis. Br J Surg 1995;82:1002

Ayeva-Derman M, Perrotin F, Lefrancq T, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: review of the literature illustrated by four cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 1999;28:800–807

Belaabidia B, Essadki O, el Monsouri A, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: apropos of eight cases and review of the literature. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2002;30:383–389

Lai ECH, Chan WC, Ma TKF, et al. The role of conservative treatment in idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Breast J 2005;11:454–456

Schelfout K, Tjalma WA, Cooremans ID, et al. Observations of an idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Peprod Biol 2001;97:260–262

Marchant DJ. Inflammation of the breast. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am 2002;29:89–102

Goldberg J, Baute L, Storey L, et al. Granulomatous mastitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:813–815

Azline AF, Ariza Z, Arni T, et al. Chronic granulomatous mastitis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. World J Surg 2003;27:515–518

Bani-Hani KE, Yaghan RJ, Matalka II, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: Time to avoid unnecessary mastectomies. Breast J 2004;10:318–322

Sakurai T, Oura S, Tanino H, et al. A case of granulomatous mastitis mimicking breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer 2002;9:265–268

Tuncbilek N, Karakas HM, Otken OO. Imaging of granulomatous mastitis: assessment of three cases. The Breast 2004;13:510–514

Wilson JP, Chapman SW. Tuberculous mastitis. Chest 1990;98:1505–1509

Fitzgibbons PL, Smiley DF, Kern WH. Sarcoidosis presenting initially as breast mass: report of two cases. Hum Pathol 1985;16:851–852

Deninger HK. Wegener’s granulomatosis of the breast. Radiology 1985;154:59–60

Stephenson TJ, Underwood TJ. Giant cell arteritis: an unusual cause of palpable masses in the breast. Br J Surg 1986;73:105

Fletcher A, Magrath IM, Riddell RH, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: a report of seven cases. J Clin Pathol 1982;35:941–945

Heer R, Shrimankar J, Griffith CDM. Granulomatous mastitis can mimic breast cancer on clinical, radiological or cytological examination: a cautionary tale. Breast 2003;12:283–286

De Hertogh DA, Rossof AH, Harris AA, et al. Prednisone management of granulomatous mastitis. N Eng J Med 1980;30:799–800

Jorgensen MB, Nielsen DM. Diagnosis and treatment of granulomatous mastitis. Am J Med 1992;93:97–101

Sato N, Yamashita H, Kozaki N, et al. Granulomatous mastitis diagnosed and followed-up by fine needle aspiration cytology, and successfully treated by corticosteroid therapy: report of a case. Surg Today 1996;26:730–733

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akcan, A., Akyıldız, H., Deneme, M.A. et al. Granulomatous Lobular Mastitis: A Complex Diagnostic and Therapeutic Problem. World J. Surg. 30, 1403–1409 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0476-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0476-0