Abstract

Introduction

Papillary microcarcinoma (PMC) is a subtype of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) associated with excellent prognosis. However, clinical and biologic behaviors of PMC may vary considerably between tumors that are clinically overt and those that are occult.

Materials and Methods

From 1964 to 2003, 185 of 628 patients with PTC were identified as having PMC, based on tumor size ≤1 cm. There were 110 overt and 75 occult PMCs detected based on clinical presentation. The clinicopathologic features, treatment, and long-term outcome of PMCs were evaluated and compared between the two groups.

Results

There were 37 men and 148 women with a median age of 45 years (range: 11–84 years). The median tumor size was 6.2 mm. Thirty-eight (21%) patients presented with cervical nodal metastases. Three (1.6%) had distant metastases and 5 (2.7%) underwent incomplete resection. Bilateral procedures were performed for 129 patients (70%) and 53 (29%) received postoperative I131treatment. During a mean follow-up of 8.2 years, 4 patients died of the disease and 13 developed recurrence. Clinically overt PMCs were significantly larger, were more likely to be multifocal, and more likely to lead to bilateral thyroidectomy. Extrathyroidal or lymphovascular invasion, nodal metastases, I131ablation, high-risk tumors, and postoperative recurrence occurred in overt PMC only. Patients with nodal metastases had a decreased survival and an increase in locoregional recurrence.

Conclusions

Despite a relatively good prognosis in PMC, a distinction should be made between clinically overt and occult PMCs in which clinically overt PMC should be managed according to tumor risk profile and clinical presentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PMC) is a specific subgroup of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) based on the size of the primary tumors of 1.0 cm or less in diameter.1Most PMCs are clinically occult and detected incidentally during pathologic examination of thyroidectomy specimens for benign thyroid diseases or during autopsy of patients who die of non-thyroid-related diseases. In addition, with the advancement of ultrasonographic imaging and fine needle aspiration cytology diagnosis for incidentally detected nonpalpable thyroid nodules,2,3occult PMC can be diagnosed with greater frequency.3Although the management of PMCs remains controversial, it is commonly accepted that this distinct variant of PTC based on size itself can be associated with excellent prognosis, and this should indirectly determine management principles.4,5

However, the fact that “not all occult papillary carcinomas are minimal” has been recognized,6and, in addition, not all PMCs remain clinically occult. A subset of patients with PMC can have a presentation that is clinically similar to conventional PTC, with cervical lymph node metastasis with or without detectable thyroid nodules as the most common clinical presentation.5–12It has been recognized that biologic behaviors of PMC may vary considerably between the really occult and the clinically overt tumors.5–7,10

In the present study, the clinicopathologic features, treatment, and outcome of PMC detected in our institution over the past 40 years was studied during a relatively long follow-up. Distinction is made between clinically overt and occult PMCs in order to compare them with regard to their clinical presentation, pathologic features, treatment delivered, and long-term outcome. Factors potentially affecting the outcome of patients with clinically overt PMC are evaluated and analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From 1964 to 2003, 185 of 628 patients with PTC were identified as having PMC based on tumor size ≤1 cm in our thyroid cancer database. Patients with PMC had a significantly better cause-specific survival (CCS) than those with conventional PTC. The 10-year CSS was 95% and 90% for PMC (n = 185) and conventional PTC (n = 443), respectively (P= 0.016) (Fig. 1). There were 75 occult PMCs detected incidentally during histologic examination of thyroidectomy specimens for benign goiters; another 110 patients with clinically detectable primary tumors or nodal metastases were included as clinically overt PMC. Tumors detected incidentally during autopsy examination of the thyroid gland of patients who died of non-thyroid-related disease and multifocal tumors in patients with conventional clinically overt PTC > 1 cm in size were excluded. Because of the occult nature of the PMC in thyroidectomy specimens for benign thyroid diseases, the size of the tumors was documented by the pathologist, usually during histologic examination. For patients with clinically overt tumors, the size of the primary tumors was frequently documented by the surgeons or pathologists before histologic examination.

Completion total thyroidectomy was not usually adopted in the presence of incidentally detected occult PMCs after unilateral lobectomy for benign goiter. Bilateral thyroidectomy with therapeutic neck dissection was the procedure of choice for PMC with cervical node metastases diagnosed preoperatively. For PMC diagnosed preoperatively without nodal metastasis, prophylactic neck dissection was not routinely performed, but suspicious lymph nodes in the central compartment were sampled accordingly. Radioiodine (I131therapy) was administered to high-risk patients who were observed to have extrathyroidal invasion, incomplete tumor excision, or cervical nodal and/or distant metastases after bilateral thyroidectomy. Patients were followed up and attended by both surgeons and oncologists at a combined thyroid cancer clinic. Thyroxine suppressive therapy was administered to patients after I131therapy, and thyroglobulin monitoring was available beginning in 1991. Follow-up data, including overall mortality, tumor-related mortality, death from other causes, locoregional recurrence, and distant metastasis were obtained. Information on details of deaths was retrieved from the Hong Kong Hospital Authority territory-wide computerized medical system, death certificates, and autopsy reports if available. Patient follow-up averaged 8.2 years (range: 0.1–38 years).

The clinical presentations, pathology, treatment, and long-term outcome of patients with PMCs were analyzed. Tumor risk profile was assigned according to commonly adopted AMES (Age, Metastasis to distant sites, Extrathyroidal invasion, and Size) risk group stratification,13Degroot classification,14UICC (International Union Against Cancer) pTNM staging,15and MACIS (Metastasis, Age, Completeness of excision, Invasiveness, and Size) scoring systems.16Comparison of clinicopathological features, treatment, tumor risk profile, and outcome was made based on the clinical presentation of PMCs. Statistical analysis was performed by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables, and by Student’s t-test to compare continuous variables between groups. Potential factors affecting the CSS including age (< 40 years and ≥ 40 years), sex, tumor size (< 5 mm and ≥ 5 mm), any evidence of extrathyroidal or lymphovascular invasion, the presence of nodal or distant metastases, the types of thyroidectomy (bilateral thyroidectomy or unilateral thyroid lobectomy), the completeness of excision (as determined by the operating surgeons), and the administration of postoperative I131ablation were evaluated in patients with clinically overt tumors. The CSS and disease-free survival (DFS) rates were calculated at 10 years after the initial surgical treatment with standard life-table methods analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method17and compared with the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS for Windows 10.0 computer software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A value of P< 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic Data, Clinicopathologic Features, and Outcome of Patients with PMC

There were 37 men and 148 women with a median age of 45 years (range: 11–84 years). There was no difference in gender ratio (male/female: 25/85 versus 12/63; P= 0.35) or age (mean ± s.d.: 45 ± 16 versus 48 ± 13 years; P= 0.1) between clinically overt and occult tumors. Eighteen patients had a history of thyrotoxicosis treated by either antithyroid medication (n = 13) and/or I131(n = 5) before presentation.

Occult PMCs were diagnosed in patients undergoing thyroidectomy for pathologies including nodular goiter (n = 57), Graves’ disease (n = 8), follicular adenoma (n = 7), and thyroiditis (n = 3). Patients with clinically overt disease presented primarily with palpable/visible thyroid nodules (n = 94), cervical lymph node metastasis (n = 13), hoarseness of voice (n = 2), or imaging (n = 1). Thirty-eight of 110 patients with overt tumors (35%) had clinically apparent cervical lymph node metastases and two (1.1%) presented with preoperative unilateral vocal cord paralysis.

Operative procedures included total (n = 98) or near total (n = 14) thyroidectomy, unilateral lobectomy (n = 56), subtotal thyroidectomy (n = 10), and completion total thyroidectomy (n = 7). Total thyroidectomy was achieved by completion total thyroidectomy after initial unilateral lobectomy in 11 patients, including 1 patient with an occult 5-mm PMC after unilateral lobectomy for a 4-cm benign thyroid nodule. Bilateral thyroidectomies were performed for 129 patients (70%) with concomitant neck dissections done for 38 of 110 patients (35%) with clinically overt PMC; including 14 functional, 12 selective, and 2 radical neck dissections, as well as 10 lymph node excisions. Three patients underwent bilateral neck dissection for extensive nodal metastases. The mean tumor size was 5 mm (median: 6.2 mm) (Fig. 2). Extrathyroidal extension was detected in 21 patients (11%). Forty-three patients had histologically documented nodal metastases (23%), and 3 had distant metastases detected at presentation (1.6%), all in the clinically overt group. Five patients (2.7%) underwent incomplete shave resection with residual tumors, and 4 received postoperative external irradiation. I131therapy was administered to 53 (48%) of 110 patients with clinically overt tumors. During follow-up, 12 patients died of unrelated causes and 4 died of recurrent cancer. Thirteen patients (7%) developed recurrent disease over a median duration of 56 months: 6 with lymph node recurrence, 5 with tumor bed recurrence, and 2 with distant metastases.

Comparison of Clinically Overt and Occult PMC

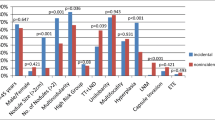

Table 1summarizes and compares the clinicopathologic features and treatment of patients with clinically overt and occult PMCs. Clinically overt PMCs were significantly larger than occult tumors (7.3 ± 2.6 mm versus 4.5 ± 2.9 mm; P< 0.001). They were more frequently greater than 5 mm in size (62% versus 31%; P< 0.001) and had a higher incidence of multifocal tumors (32% versus 12%; P= 0.002) than occult PMCs. Extrathyoidal extension (P< 0.001), lymphovascular invasion (P= 0.002), and cervical lymph node metastases (P< 0.001) occurred in patients with overt tumors but not in those with occult tumors. A higher proportion of patients with clinically overt tumors than with occult PMC underwent bilateral thyroidectomy. Of 75 patients (53%) with occult tumors, 40 underwent bilateral thyroidectomy, whereas 89 of 110 (81%) patients with clinically overt PMC had the bilateral procedure (P< 0.001). In addition, postoperative I131was administered to 53 of 110 patients (48%) with clinically overt PMC only (P< 0.001). High-risk tumors, as defined by AMES risk group stratification, Degroot classification (> stage I), UICC pTNM staging (> stage I) were present in overt PMC only. Although there was no significant difference in MACIS score between overt and occult tumors (4.4 ± 1.4 versus 4.2 ± 0.9; P= 0.2), 30 of 110 (27%) patients with overt tumors had a MACIS score > 5 compared with 10 of 75 (13%) patients with occult PMC (P= 0.017) (Table 2). Postoperative recurrence developed in 13 of 110 patients with overt PMC only (P= 0.003).

The 10-year CSS and DFS was 94% and 87%, respectively, for overt PMC. None of 75 patients with occult PMC compared with 4 of 110 patients with overt PMC died of thyroid carcinoma (P= 0.15). There was no significant difference in CSS (P= 0.19) between clinically overt and occult PMC, but overt tumors had a significantly lower DFS than occult PMC (P= 0.05; Fig. 3). The details of four patients with PMC who died of thyroid carcinoma are summarized in Table 3. Potential risk factors for decreased survival were analyzed in patients with clinically overt tumors only. Old age (> 40 years at presentation) (P= 0.04), tumor size (≥ 5 mm) (P= 0.018), the presence of extrathyroidal invasion (P= 0.004), cervical lymph node (P= 0.046) or distant metastases (P< 0.0001), incomplete resection (P< 0.0001) and postoperative recurrence (P< 0.0001) are risk factors for decreased survival. Among those patients with lymph node metastases, 36 (95%) underwent bilateral thyroidectomy and 28 (74%) received I131ablation. The CSS and DFS of patients with cervical lymph node metastases were less favorable than for those without lymph node metastases (Fig. 4). Patients with nodal metastases also had a higher incidence of locoregional recurrence. Four of 72 patients without nodal metastases developed locoregional recurrence compared with 7 of 38 patients with nodal metastases (P= 0.045).

DISCUSSION

Clinically undetectable or occult thyroid cancer is very common, and the description of this entity has been evolving over time.4,5According to the latest World Health Organization histologic classification, the term “papillary microcarcinoma” defines a tumor focus of 1.0 cm or less in diameter; it replaces the term “occult” and describes this subgroup of tumors.1Although these tumors represent distinct entity with stringent but simple diagnostic criteria, the clinical relevance of PMCs remains uncertain, and there is much controversy with respect to their clinical manifestation, molecular origin, biological behavior, prognosis, and optimal management.4,5,18In addition, the term “small” (≤1.5 cm) tumors is still commonly used.19

Papillary microcarcinoma is a common finding during autopsy and histologic examination of thyroidectomy specimens for benign diseases. In autopsy series, the incidence of occult or small PTC varied from 1% to 35.6% in patients who died of non-thyroid-related diseases,4and the incidence of incidental or multifocal PMC during thyroidectomy for benign goiter was 0.8%–10.8%.4Although the prevalence of thyroid carcinoma has been steadily documented to be increasing, there is, an obvious discrepancy between the prevalence of clinically recognized thyroid carcinoma and PMC. The rise in prevalence is attributed to the increasingly diagnosed PMC.5With advanced diagnostic imaging such as ultrasonography and improved preoperative diagnostic technique such as fine needle aspiration, PMCs can also be diagnosed definitively for surgical treatment and hence are not clinically occult.2–5,9

Disease-specific death in PTC is uncommon and is particularly rare in low-risk patients, including those with PMC.8,11,12,20,21In a study of 535 patients with PMC for whom follow-up data are available for 17.5 years, two patients died of thyroid carcinoma, and all-causes survival did not differ from expected.8Similarly, reports on large series of patients with a relatively long follow-up showed that disease-specific death was a rare event, even though a significant proportion of patients developed recurrence.8–11,19,20Sampson et al. concluded that even if occult thyroid carcinomas had metastasized locally, they rarely affected the patient’s life or health.21As in other reports,8,14the present study confirmed that PMC could be identified as a specific subgroup of papillary thyroid cancer with an overall improved prognosis.4Papillary microcarcinoma patients have an overall low risk for disease mortality, according to commonly used risk group stratification or staging systems, and their overall survival should be significantly better than other PTC patients.

Although the overwhelming majority of PMCs are clinically occult, a significant proportion of patients can present clinically with symptoms similar to conventional PTC. Patients with PMCs can present with a visible or palpable thyroid nodule, symptoms related to local invasion, cervical nodal metastases and, rarely, distant metastases. Cervical nodal metastasis with or without a linically detectable thyroid nodule is the most commonly reported presentation.7–11Papillary microcarcinomas detected incidentally during autopsy or histological examination may represent a different form of tumors compared with clinically overt tumors. For studies identifying occult tumors as a subgroup, the proportion of occult or incidental PMCs ranged from 13% to 83%,8–12,19depending on differences in the selection criteria, data collection, histological reporting, and management protocols. In the present study, occult PMCs accounted for 41% of all PMCs and behaved indolently, like a benign tumor, without any risk of invasiveness, metastases, recurrence, or mortality. Commonly used tumor risk group stratification and staging systems identified them as extremely low-risk and distinguished them from clinically overt tumors. Although early surgical treatment before clinical manifestation might account for the excellent clinical outcome, aggressive treatment such as completion total thyroidectomy, prophylactic neck dissection, and postoperative adjuvant radioiodine is not indicated for this subgroup of PMCs when diagnosis has been confirmed. Patients with incidentally detected PMC diagnosed after surgery should be treated as if they had a benign disease. The issue of whether to inform the patient of a “cancer” diagnosis,22because of its potential social and economic implications, should be left to the individual surgeon to decide.4As increasing numbers of occult PMCs are diagnosed preoperatively with the wide application of ultrasonography screening and fine needle aspiration cytology,2,3the question arises whether patients with occult PMCs without clinical manifestation could be managed by nonoperative means. This needs further evaluation as well as longer term follow-up,23,24although most patients would prefer therapy to observation.25

For patients with clinically overt PMCs, distinction should be made for those presenting with cervical lymph node metastases. Cervical nodal metastases in patients with PMC at presentation are frequently associated with recurrence8,9and occasional disease-related death.9The incidence of PMC presenting with cervical nodal metastases ranged from 9.3% to 32%.8–11In addition, histologically documented nodal metastasis could occur in the central and lateral compartments of 60.9% and 39.5% of PMC patients without clinically detectable nodal metastases after prophylactic neck dissection.9Nodal recurrence was more common in patients presenting with palpable nodal metastases (16.7%), despite therapeutic neck dissection; however, prophylactic neck dissection was not recommended for patients without clinically palpable nodal metastases because nodal recurrence did not differ between the prophylactic and the no-dissection group.9In the present study, prophylactic neck dissection was not routinely performed for PMC patients without nodal metastases, and radioiodine was administered to the majority of them after bilateral thyroidectomy. The presence of cervical lymph node metastases was associated with decreased survival and an increase in locoregional recurrence. Although the impact of surgical treatment or radioiodine in reducing recurrence could not be demonstrated in the present study, others have shown the role of either bilateral thyroidectomy8or I131ablation19in decreasing locoregional and lymph node recurrence of PMCs. Dissection of nonpalpable lymph nodes is probably not essential as long as postoperative I131is planned.25

It is difficult to group all PMCs together and to recommend a management strategy based solely on size because of the heterogeneous presentation of this disease.4The nature of surgical therapy should depend on the clinical presentation and must be achieved with minimal morbidity.4In addition to the presence of cervical nodal metastases, other commonly used risk factors such as old age, incomplete excision, presence of distant metastases, and postoperative recurrence have been identified as prognostic factors for poor survival in patients with clinically overt PMCs. As with other types of PTC, risk profile consideration should be applied for the management of individual PMC patients. Near-total thyroidectomy with radioiodine should be considered to decrease locoregional recurrence for low risk14or early stage disease26and be recommended for the management of high-risk patients.27

In conclusion, patients with PMC have an overall excellent prognosis, although the distinction needs to be made with reference to the clinical presentation. Clinically occult tumors are invariably incidental and indolent in behavior, whereas those that are clinically overt demonstrate more aggressive behavior. In evaluating patients presenting with clinically overt disease, selected high-risk patients could be identified by the commonly adopted risk group stratification or staging systems. In addition, patients presenting with cervical nodal metastases are at risk of recurrence and disease-related death. In such cases, more aggressive treatment achieved with an acceptable level of morbidity can be considered. In addition to using clinical presentation as the basis for management, treatment should be individualized, preferably by risk group stratification and not by considering patients with PMC as a specific subgroup.

References

Hedinger CE, Williams ED, Sobin LH. Histological typing of thyroid tumours. In Hedinger CE, editor. International Histological Classification of Tumors, vol 11, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1988:7–68

Ross DS. Nonpalpable thyroid nodules: managing an epidemic. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:1938–1940

Papini E, Guglielmi R, Bianchini A, et al. Risk of malignancy in nonpalpable thyroid nodules: predictive value of ultrasound and color-Doppler features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:1941–1946

Bramley MD, Harrison BJ. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid gland. Br J Surg 1996;83:1674–1683

Piersanti M, Ezzat S, Asa SL. Controversies in papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:183–191

Allo MD, Christiansen W, Koivunen D. Not all “occult” papillary microcarcinomas are “minimal.” Surgery 1988;104:971–976

Woolner LB, Lemmon ML, Beahrs OH, et al. Occult papillary thyroid carcinoma of the thyroid gland: a study of 140 cases observed in a 30 year period. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1960;20:89–105

Hay IH, Grant CS, van Heerden, et al. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 535 cases observed in a 50-year period. Surgery 1992;112:1139–1147

Wada N, Duh Q-Y, Sugino K, et al. Lymph node metastasis from 259 papillary thyroid microcarcinomas. Frequency, pattern of occurrence and recurrence, and optimal strategy for neck dissection. Ann Surg 2003;237:399–407

Sugitani I, Yanagisawa A, Shimizu A, et al. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies of papillary thyroid carcinoma presenting with cervical lymphadenopathy. World J Surg 1998;22:731–737

Baudin E, Travagli JP, Ropers J, et al. Microcarcinoma of the thyroid gland. The Gustave-Roussy Institute experience. Cancer 1998;83:553–559

Rodriguez JM, Moreno A, Parilla P, et al. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: clinical study and prognosis. Eur J Surg 1997;163:255–259

Cady B, Rossi R, Silverman M, et al. Further evidence of the validity of risk group definition in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Surgery 1985;98:1171–1178

DeGroot LJ, Kaplan EL, McCormick M, et al. Natural history, treatment, and course of papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endcorinol Metab 1990;71:414–424

UICC (International Union Against Cancer). TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 5th Edition, Sobin LH, Wittekind C, editors. New York; Wiley, 1997

Hay ID, Bergstralh EJ, Goellner JR, et al. Predicting outcome in papillary thyroid carcinoma: development of a reliable prognostic scoring system in a cohort of 1779 patients surgically treated at one institution during 1940 through 1989. Surgery 1993;114:1050–1058

Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparameteric estimation from incomplete observation. J Am Stat Assoc 1958;53:457–481

Shattuck TM, Westra WH, Ladenson PW, et al. Independent clonal origins of distinct tumor foci in multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2406–2412

Pellegriti G, Scollo C, Lumera G, et al. Clinical behavior and outcome of papillary thyroid cancers smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter: study of 299 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:3713–3720

Chow SM, Law SCK, Chan JKC, et al. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and multifocality. Cancer 2003;98:31–40

Sampson RJ, Oka H, Key CR, et al. Metastases from occult thyroid carcinoma: an autopsy study from Hiroshima and Nagasaki Japan. Cancer 1970;25:803–811

Frauenhoffer CM, Patchetsky AS, Cobanoglu A. Thyroid carcinoma, a clinical and pathologic study of 125 cases. Cancer 1979;43:2414–2421

Ito Y, Uruno T, Nakano K, et al. An observation trial without surgical treatment in patients with papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid. Thyroid 2003;13:381–387

Ito Y, Tomoda C, Uruno T, et al. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid: how should it be treated ? World J Surg 2004;28:1115–1121

Pearce EN, Braverman LE. Editorial: Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma outcomes and implications for treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:3710–3712

Loh KC, Greenspan FS, Gee L, et al. Pathologic tumor-node-metastasis (pTNM) staging for papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomas: a retrospective analysis of 700 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:3533–3562

Lo CY, Chan WF, Lam KY, Wan KY. Optimizing the treatment of AMES high risk papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg 2004;28:1103–1109

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lo, CY., Chan, WF., Lang, B.HH. et al. Papillary Microcarcinoma: Is There Any Difference between Clinically Overt and Occult Tumors?. World J. Surg. 30, 759–766 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0363-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0363-8