Abstract

Ecotourism development is closely associated with the sustainability of protected natural areas. When facilitated by appropriate management, ecotourism can contribute to conservation and development, as well as the well-being of local communities. As such, ecotourism has been proposed and practiced in different forms in many places, including China. This study assesses ecotourism development at Xingkai Lake National Nature Reserve in Heilongjiang Province, China. Key informant interviews were conducted with representatives from the provincial Forestry Department, the Nature Reserve, and the local community. Observation was undertaken on three site visits and secondary data were collected. The potential for providing quality natural experiences is high and tourism development is occurring rapidly. However, current relationships between people, resources, and tourism have yet to provide mutual benefits necessary for successful ecotourism. The multi-stakeholder management style and the ambiguity of landownership within the nature reserve constitute structural difficulties for ecotourism management and operation. Although participation in ecotourism could provide a livelihood opportunity and interests in involvement in tourism have been identified among the local fishing community, current involvement is limited mainly due to the lack of mechanisms for participation. Therefore, it is recommended that management programs and government policies should be established to provide a platform for community participation in ecotourism. Then, a positive synergistic relationship between tourism, environment, and community could be developed. Planning and policy requirements are discussed for ecotourism development in protected areas in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The concept and practices of ecotourism have been widely discussed since the term was created in 1980s. If appropriately managed, ecotourism can contribute to development and conservation at protected areas, and the economic and social enhancement of local communities (Wall 1997; Weaver 2001). Therefore, ecotourism has been and is practiced in and around many parks and protected areas in various forms throughout the world. Due to the special relationships that commonly exist between the resources and the local community at protected areas, the potential of ecotourism as a supplementary or alternative livelihood strategy for local communities is frequently emphasized (Ross and Wall 1999a, b; Zeppel 2006; Xu et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2013).

Community participation in and benefits from tourism are embedded in the very concept of ecotourism (Brandon 1993; Ross and Wall 1999a, b). Since local livelihoods are usually closely related to the natural resources of protected areas, community participation in ecotourism is not only desirable but necessary for true ecotourism to occur. Changes in local lifestyles are usually required when ecotourism is introduced as traditional resource-consumptive livelihood methods are often no longer in line with the goals for protected areas. Ecotourism is widely perceived as being capable of facilitating changes in local livelihoods that are compatible with tourism and conservation (Simmons 1994; Zeppel 2006; Xu et al. 2009). However, for this to occur, interests, roles, and responsibilities of key stakeholders need to be clarified (Liu et al. 2013), such as the roles of different levels of governments, the management agency, and the community. The provision of high-quality tourism experiences, conservation of protected area resources and compatibility with the lifestyles, and aspirations of the local community should be simultaneously achieved.

Taking Xingkai Lake National Nature Reserve in Heilongjiang Province as an example, this study assesses the status of ecotourism through exploration of the complex relationships between tourism, resources, and community. Perspectives of the government, the management agency, and the community will all be addressed. The paper demonstrates a rationale for the application of ecotourism in the development of protected areas and the importance of community participation in this endeavor. Planning and policy requirements are discussed for directing appropriate management strategies for ecotourism and that can facilitate effective community involvement in protected areas in China, where definitions and applications differ somewhat from those prevalent in the western world.

Literature Review

Ecotourism and Protected Areas

Although there are different views regarding the concept and connotation of ecotourism, it is commonly agreed that ecotourism is about aligning resource conservation, community development, and tourism (Boo 1993; Honey 1999; Wall 1996; Stone and Wall 2003), with specific objectives in the above areas that may vary from place to place. Environmental, economic, and social sustainability are all critical aspects of ecotourism development (Weaver 2001); and the need for environmental education to occur for both tourists and locals is frequently acknowledged (Christopoulou and Tsachalidis 2004). Ecotourism is often considered to be a development tool that can attract financial and political support for management and conservation at protected areas (Boo 1993; Wall 1996; Honey 1999).

Commonly taking place in environmentally and economically fragile locations (Giannecchini 1993), and considered as a potential strategy supporting conservation of natural ecosystems and promoting sustainable local development (Wall 1996; Ross and Wall 1999a, b), ecotourism is widely associated with parks and protected areas. If facilitated by appropriate management, ecotourism can contribute to the sustainability of protected areas through improving the well-being of local communities, enhancing public awareness of the value of the environment and natural resources, and providing financial support for conservation, particularly in marginal regions that lack viable economic alternatives (Weaver 2001). Thus, a positive synergistic relationship between tourism, resources, and community can be constructed (Ross and Wall 1999a, b; Xu et al. 2009). However, ecotourism when used as an agent of change requires the creation of new understandings, new tourism experiences, new social relationships, new links between people and environment, modified resource allocation and utilization, altered skills and livelihood methods, and novel management regimes (Wall 1996; Stronza and Pêgas 2008).

Zhao and Wu (2009), in their study of ecotourism in wetland nature reserves in China, reiterated the interactive relationships between resources, ecotourism, and the community and highlighted the potential contribution of ecotourism to local livelihoods. However, the understanding of shengtai lüyou (the Chinese term for ecotourism) may have slightly different connotations from those commonly espoused in the west, with a stronger emphasis on development, a greater willingness to accommodate larger groups, more frequent mention of health, and interpretation that embraces cultural stories as much as scientific principles (Donohoe and Lu 2009; Buckley et al. 2008; Cui et al. 2012).

Given that ecotourism involves multiple goals, it inevitably involves stakeholders with different interests, roles, and responsibilities (Shams 2012; Liu et al. 2013). Moreover, the existence of varied land tenure regimes within a protected area fragments resources, habitats, and management practices (Fitzsimons and Wescott 2008a, b). Therefore, lack of connectivity and integration among management bodies is identified as a key problem in protected area management (Fitzsimons and Wescott 2008a, b). This is particularly the case for ecotourism management in China, where protected areas fall under multiple jurisdictions; and there is no national ecotourism strategy for protected areas (Li and Han 2001). The concept of a multi-tenure reserve network (MTN) has been proposed to address such a situation, aiming to facilitate communication, information exchange, and management activities among land managers with differing tenures and responsibilities, thereby improving management and protection (Fitzsimons and Wescott 2008a, b). Although China has a distinctive land tenure system, the MTN concept draws attention to the importance of cross-sector communication and cooperation to support consistency in management standards and practices for ecotourism at protected areas.

The creation of protected areas involves the imposition of administrative and political boundaries which may cause lack of connectivity and inconsistency in resource conservation and management (Timothy 2000; Ioannides et al. 2006). If protected areas are adjacent to international borders, the involvement of administrators in neighboring countries may be necessary (Timothy 2000; Hamilton 2001). Their research further indicates that cross-border cooperation in the management of ecosystems can facilitate the standardization of conservation management on both sides of the border, benefiting the protection of migratory species, shared water bodies, and scenic landscapes. Transboundary collaboration can be critical for visitor management and marketing efforts (Timothy and Teye 2004) and can enhance the comparative advantages of the site (Ioannides et al. 2006). However, competition between businesses on either side of the border may be enhanced and tensions may arise when the respective national interests do not coincide with the mutual benefits gained through transboundary collaboration at the regional and local levels (Ioannides et al. 2006). Therefore, the success of transboundary collaboration between cross-border protected areas depends on whether equilibrium among interest can be achieved in the conservation and use of resources, including ecotourism development.

Community Participation in Ecotourism

Ecotourism development usually involves a wide variety of stakeholders, including tourists, residents, governments, managers, and so on (Ceballos-Lascurain 1993; Tsaur et al. 2006). Much research confirms the importance of understanding the needs and interests of local communities and facilitating their involvement in ecotourism (Russell 2007; Lim and Mcaleer 2005). As one important stakeholder, the community plays multiple roles in ecotourism (Scheyvens 2003). As one essential element in its conceptualization, ecotourism should involve effective community participation and equitable sharing of benefits (Brandon 1993; Ross and Wall 1999a). The community should be empowered to participate, to monitor, and to benefit from ecotourism (Chen 2006). Chinese scholars concur with this perspective. For example, Deng and Wu (2006) stated that community-based ecotourism can facilitate the sustainable development of resources and local culture, and maximize local benefits from tourism

In addition, local participation in ecotourism can enhance the communities’ recognition and appreciation of the value and significance of their culture and resources, and strengthen their awareness of the importance of resource conservation (Foucat 2002). Economic benefits from ecotourism participation, income and employment, are identified as important incentives for local communities to support conservation efforts (Malek-Zadeh 1996; West 2006), with cases being reported in developing countries such as Ecuador (Wunder 1999) and Nepal (Spiteri and Nepal 2006).

Local participation in ecotourism can also reduce a community’s reliance on resource-consumptive activities, such as commercial agriculture, hunting, and logging (Langholz 1999). Stronza and Pêgas (2008) suggested that the capacity for collective action of local institutions can be strengthened and the overall social and economic stability can be enhanced through engagement in managerial positions in ecotourism. Local decisions to conserve natural resources will then be encouraged (Stronza and Pêgas 2008). They further argued that although economic benefits may be important for short-term conservation, greater local involvement in ecotourism management may make a long-term contribution to the success of both conservation and community development. Moreover, ecotourism-related facilities can be used to enrich the cultural life of local residents and support environment-related public campaigns and educational activities to enhance socio-cultural impacts.

In spite of the potential to establish a synergetic relationship between community and ecotourism at protected areas, there are often immediate conflicts between local economic interests and biodiversity conservation (Salafsky and Wollenberg 2000). Traditional livelihood methods may not be in line with conservation goals. Local involvement in ecotourism in protected areas often leads to the replacement of traditional resource-consumptive livelihoods. But this livelihood change, in turn, can support sustainability by strengthening relationships between the ecotourism industry and conservation efforts (Murphy 1985; Simmons 1994; Xu et al. 2009). However, local residents seldom have real power in tourism planning and management (Scheyvens 2003); and they are often marginalized by tourism development (Kiss 2004; Xu et al. 2009). Appropriate institutional and legal arrangements are necessary to ensure community participation both in decision making and benefit sharing through ecotourism development at protected areas (Li and Han 2001; Liu et al. 2013).

Community participation in tourism has been restricted in the Chinese context due to lack of participation mechanisms (Li 2005; Bao and Sun 2006; Hou et al. 2007). In particular, little attention has been paid to changes in lifestyle, social relations, and the power structure of the community that result from participation in tourism. Xu (2005) found that, in China, residents have limited knowledge of ecotourism and their knowledge comes primarily from the government. Limited understanding reduces local support for ecotourism development (Wu et al. 2005). Thus, especially in China where governments at all levels are prominent in establishing development direction, the relevant government departments and the management agency should embrace the roles and responsibilities of conducting ecotourism education and facilitating community participation.

Although NGOs play a less prominent role in China than in many developing countries, as outsiders with expertise and influence, they can play a role in working toward equilibrium of interests among multiple stakeholders in ecotourism development in protected areas, particularly in eliciting the voices of local residents. For example, supported by a World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) project, the local Tibetan Baima people at China’s Wanglang National Nature Reserve were consulted in ecotourism development and have become engaged in conservation and tourism activities. This has reduced poaching and increased local incomes, enhancing the balance between resource conservation and local development (Lian 2005; Zeppel 2006). However, NGOs, even those that are internationally recognized, are seldom directly involved in the management of protected areas and their visions need to be implemented through local governments and management agencies.

Assessing Ecotourism at Protected Areas

As the definition of ecotourism is made more complex and inclusive of multiple objectives, in practice it becomes increasingly difficult to meet a diversity of objectives simultaneously (Stone and Wall 2003; Gössling 1999; Wunder 2000), particularly when confronted with complex natural, social, and economic situations (Xu et al. 2009). Many cases show that ecotourism has fallen short of the objectives set for it (Ross and Wall 1999b; Stone and Wall 2003; Xu et al. 2009), demonstrating the complexity of ecotourism planning and management. The gap between ecotourism theory and practice confirms the need to identify reasons hindering the realization of objectives and opportunities for improvement (Xu et al. 2009). This is particularly the case for ecotourism at protected areas where both natural and socio-economic systems are involved (Spiteri and Nepal 2006; Xu et al. 2009).

Few attempts have been made to assess the status of ecotourism at destinations, primarily due to the numerous interrelated variables (Wall 1996) and the lack of standardized assessment frameworks (Ross and Wall 1999a, Tsaur et al. 2006). Gössling (1999) pointed out that substantial changes often need to be made to achieve ecotourism objectives, such as the introduction of strategies to accommodate tourists, education of both visitors and locals, and efficient site management. Employment opportunities and tourism revenue are often used as assessment indicators (Davis et al. 1988). Local community attributes and perceptions are considered to be important parameters, due to their links with tourism, biodiversity conservation, and protected area management (Spiteri and Nepal 2006; Xu et al. 2009).

Several frameworks exist that could be used to assess the environmental impacts of ecotourism. For example, Mason and Moore (1998) applied the Sorensen Network, a well-known method employed in environmental impact assessment (Monavari and Fard 2011), to identify the potential direct and indirect environmental impacts of ecotourism and to analyze the effects of ecotourism activities on marine environments and their causes. Integrative ecological sensitivity (IES) analysis is another means of assessing the environmental impacts of tourism at nature reserves through evaluating the interrelationships between multiple ecological characteristics of landscapes and ecotourism activities (Zhang et al. 2012).

From an economic perspective, the contingency evaluation method (CVM), a widely used non-market valuation method, has been employed to assess the economic value of environmental commodities with several applications to ecotourism (Lee and Mjelde 2007; Chen and Law 2012). For example, Chen and Law (2012) applied CVM to assess the economic value of recreational forest trails in Taiwan through estimating residents’ and visitors’ willingness to pay (WTP) for forest conservation. They found that trails have significant value as ecotourism resources and that local residents perceive higher values than visitors due to their higher use of and reliance on the trails.

The perceptions of both residents and experts have been used to provide broader perspectives on the consequences of ecotourism. For example, Nyaupane and Thapa (2004) compared ecotourism between a long-established traditional tourism area and a recently created ecotourism site at a conservation area in Nepal. They assessed residents’ perceptions of environmental, economic, and socio-cultural impacts of ecotourism activities. Deng et al. (2011) used a two-round Delphi survey of academics and ecotourism operators and a point system to quantified indicators of destination conditions and destination management. However, the validity of this work has been criticized (Garrod 2012; Deng and Selin 2012).

The above studies either take a partial or an indirect perceptual approach to the assessment of ecotourism. In contrast, a broader framework to guide the assessment of ecotourism has been proposed by Ross and Wall (1999a, b). They suggest assessment through examination of the relationships among community, tourism, and environment, which are commonly agreed to be key elements in ecotourism (Wall 1996; Ross and Wall 1999a, b; Tsaur et al. 2006). As shown in Fig. 1, they suggested that positive synergistic interrelationships between these three elements, achieved through effective policies and management, are required for successful ecotourism (Ross and Wall 1999a, b). The framework has proven to be an effective tool to guide a holistic evaluation of key aspects of ecotourism. It has wide applicability in the assessment of ecotourism (as well as other forms of tourism) and can aid in the identification of enhanced management strategies for ecotourism in protected areas. It has been applied in three nature reserves in Sulawasi, Indonesia (Ross and Wall 1999a), and in Taiwan (Tsaur et al. 2006).

Ross and Wall’s framework and the associated documentation (1999a) identify management factors that may influence the success of ecotourism. However, it may be difficult to take novel initiatives in specific cases, particularly in the Chinese context. Su and Wall (2011) identified a hierarchical multi-stakeholder management structure in heritage management in China, reflecting it’s political and land ownership systems that is complex and difficult to negotiate if new management strategies are to be introduced. The way in which the stakeholders are organized and how decisions are made will influence the ways in which relationships between environment, community, and tourism can be manipulated. Therefore, considering the Chinese context, a simplified list of key management parameters is proposed to assess the management component of ecotourism (Table 1).

As shown in Table 1, management organizations, management policies/plans, and management operation are identified as the three key management parameters. Second tier indicators to illustrate the status of ecotourism management are suggested in each category. Management organizations are evaluated according to the management structure, stakeholders, ownership of the land and associated resources, the sources of income, and the type of management body. The latter three have been identified by Eagles (2009) as three key functional aspects of parks and protected areas management. Policies are divided into five sub-categories to illustrate whether relevant policies or plans are in place to encourage positive interrelationships between environment, community, and tourism. Management operation is categorized into resource use monitoring (zoning), environmental quality monitoring (air, soil, water, wildlife etc.), environmental education program for the community and/or tourists, tourism monitoring (tourist number, activities, behaviors, distribution etc.) and tourism service provision (transportation, facilities/activities, catering, accommodation etc.). The indicators can be used to supplement Ross and Wall’s framework (1999a, b) to illustrate the status of ecotourism management in protected areas and identify areas requiring improvement.

Ecotourism in Protected Areas in China

The number of protected areas in China increased from 34 in 1978 to 2,640 in 2011, accounting for 14.93 % of the country’s territory (SEPA 2012). The complicated management structure of protected areas in China has been well recorded. It involves multiple departments across national, provincial, and local levels (Su 2004; Wang et al. 2006; Xia et al. 2009; Zheng 2010; Su and Wall 2011, 2012). The type of resources in the protected area also affects the involvement of related departments in its management structure, such as forestry, agriculture, water resources, culture, and many others, (Wang et al. 2006; Zheng 2010; Su and Wall 2011, 2012). Moreover, protected areas in China usually have a complicated and overlapping landownership structure, which differs among protected areas due to political and historical reasons (Zhou and Wen 2006; Zhou et al. 2009). According to Zhou and Wen (2006), only 52.1 % of nature reserves in China have full ownership rights over their territory and 15.8 % have no land ownership right. This situation leads to structural difficulties in protected area management in China, which seriously hamper both operation and development (Zhou and Wen 2006; Xia et al. 2009; Zheng 2010; Su and Wall 2011, 2012) and directly affects how and to what extent the local community is involved and how much they can benefit.

Mostly located in remote and less-developed regions (Han 2000; Xu et al. 2009), China’s protected areas are under economic development pressure to finance their operation and support local populations (Xu et al. 2009). Therefore, ecotourism has been promoted and practiced as a strategy to foster beneficial relationships between environment, community, and tourism in many nature reserves in China. However, ideal relationships are usually difficult to realize when confronted with complex natural, social, and economic situations and the above-mentioned structural barriers (Xu et al. 2009; Xia et al. 2009; Zheng 2010).

According to Zeppel (2006), Wanglang National Nature Reserve in Sichuan Province became the first international-standard ecotourism destination in China. Supported by a WWF project, Wanglang features small-scale ecotourism products and the active engagement of multiple stakeholders in order to achieve both conservation and development (Lian 2005). Resource conservation is promoted through controlled access and constant monitoring (Lian 2005). In 2001, it became the first ecotourism program in China certified by the Australian-based Nature and Ecotourism Accreditation Programme (NEAP). International support, management commitments, community participation, and small-scale development focusing on long-term benefits underpin the success of ecotourism at Wanglang Reserve (Lian 2005; Zeppel 2006). It is worth noting that its management agency, formerly a state-owned forestry farm, has full use and management rights over the reserve (WNNR Website 2014), which has enabled it to exercise a higher level of control in reserve management.

Although substantial research has been undertaken on ecotourism in China, most studies focus on financial and environmental issues in the reserves themselves and possible solutions. Limited attention has been given to the status of local communities and their relationships with tourism and conservation (Xu et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2013). When considered, the attitudes and behaviors of local people are usually viewed as being factors that influence the successful development of ecotourism. The capacity of communities to participate in and harmonize development and conservation is not sufficiently recognized (Xu et al. 2009). Moreover, studies of community participation in ecotourism are usually undertaken through a single approach: questionnaire surveys (Xu 2006; Wang 2010). Governments and management agencies have seldom been examined in research to understand the perceptions, responsibilities, and roles of these stakeholders in community participation at protected areas.

Because land in China ultimately belongs to the nation, residents only have the rights to use the land (Bao and Sun 2006), which affects how residents use the land and their attitudes toward it. These special features have granted governments and the management agency important roles and responsibilities not only in planning and managing protected areas, but also in facilitating and regulating community participation. Xu et al. (2009) emphasized the important role of the management agency as a coordinator to facilitate the establishment of benign relationships among the various stakeholders, including local residents. Therefore, the perspectives of the management agency and governments should be included when exploring community participation in ecotourism in the Chinese context.

Taking Xingkai Lake National Nature Reserve in Heilongjiang Province as a study site, this study examined ecotourism development from the perspectives of governments, the management agency, and the community. The Ross and Wall (1999a, b) framework is used to assess the status of ecotourism development at the site. In addition, the status of ecotourism management and how it affects the achievement of synergetic relationships between environment, tourism, and community are further discussed using the parameters identified in Table 1.

Research Methods

A mixed methods approach was adopted to collect and analyze data, enabling cross-checking, and triangulation of findings. Key informant interviews, participatory observation, and review of secondary data were the major research methods employed.

Key informants were contacted through referrals and interviewed during three periods of field investigations between April 2010 and May 2011 (Table 2). In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with management officials at the two major management bodies: Heilongjiang Provincial Forestry Department and the Management Agency of the Reserve. Unstructured interviews occurred with local community members.

Officials of Heilongjiang Provincial Forestry Department were asked about the condition of resource conservation and tourism development, the development objectives, management structure, major problems and challenges, tourism development objectives and plan, and issues concerning the local community. Interviews with officials from the Management Agency of the Reserve explored the management structure, the current situation and challenges of resource conservation, tourism development, and local communities of the reserve. Emphasis was placed on interviewing government officials and opinion leaders. As holders of public office, they are used to responding to questions and permission is not required. In the Chinese context, it is uncommon to seek ethics approval to undertake research and the infrastructure is not in place to grant such approvals. However, it is usual to get permission to undertake research from senior officials, whose approval is likely to affect the willingness of others to provide information. Furthermore, such individuals are likely to have had a role in making decisions and opinions acquired. Of course, opinions acquired from government officials may represent only an official perspective and some issues may not be discussed due to confidentiality or political sensitivity. Therefore, efforts were made to acquire information from different departments to ensure a variety of perspectives could be obtained to undertake cross-checking and validation.

A convenience sample and unstructured interviews were used to explore the views of local residents. Undertaking a random sample is not feasible because of the lack of a sample frame and many local residents have low education levels and are unfamiliar with and reluctant to complete questionnaires, although they are willing to talk off-the-record. Six community members who were encountered during the field investigations were interviewed to understand their current living standards, livelihood strategies, and their attitudes toward ecotourism development. Each interview lasted 20–30 min.

Content analysis was used to analyze the interview data. The assessment framework (Fig. 1; Table 1) guided the identification of themes and relationships between them, with an emphasis on ecotourism-induced interactions between environment, tourism, and the community. Facts and opinions related to each theme were clustered, compared, and summarized.

In addition, observations and secondary data were used to complement the interview data. Observations were made throughout the three field visits on the characteristics of natural and cultural resources and the conditions of resources conservation, tourism activities and facilities, and communities in and around the reserve. For example, sources of pollution from waste from tourism development were observed from a wetland boardwalk. Secondary data were collected and reviewed, such as tourism statistics, government policies, regulations, and plans, including Jixi Eco-city 11th Five Year Plan, Tourism Master Plan for Jixi City of Heilongjiang Province (2010), Management Regulations of the reserve since 2007, Fishing Regulations of the reserve, Working Policies of the Management Agency of the reserve and Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands.

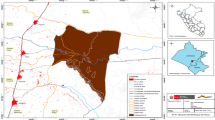

Xingkai Lake National Nature Reserve (The Reserve)

Xingkai Lake National Nature Reserve is located in the Sanjiang Plain on the border between China and Russia, about 130 km from Jixi City. With an area of 222,488 ha, it embraces the Small Xingkai Lake and one quarter of the Big Xingkai Lake, which is shared by China and Russia, and its surrounding wetland area. First established in 1986, the Reserve became a National Nature Reserve in 1994. A transboundary nature reserve agreement was established in 1992 with the Khank Nature Reserve in Russia and another in 1996 for joint management of the whole of Big Xingkai Lake. Other than limited joint research on shared water resources and species of Big Xingkai Lake, not much collaboration has occurred between China and Russia leading to real actions, particularly for tourism. Indeed, China does not have a good or extensive record of cooperation regarding international waters (Biba 2014). Currently, the management of the Reserve is a local matter targeting a predominantly local market. Nevertheless, management and use of resources at the local scale do potentially have transboundary affects for lake-wide water quality and quantity, as well as migratory species. Therefore, the potential for transboundary governance for the sustainable use and management of resources is present but has yet to be realized (Fig. 2).

The Reserve is a complex temperate inland wetland ecosystem, featuring grassland, marshes, lakes, and forests. About 460 higher plant species, 65 fish species, and 341 vertebrate species are present at the reserve (data from the Reserve). It is also an important bird migration stop and breeding habitat with about 235 species of migrating birds, of which nine species are first-class national protected birds.

Due to its importance and value for wetland protection and biodiversity preservation, the Reserve has gained considerable recognition. It was in the first group to join the North East Asian Crane Site Network in March 1997 and designated by the United Nations as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance in January 2002. The Reserve is also a National Geological Park, a Provincial Scenic Spot, and a National Human and Biosphere Reserve. In addition, the Reserve hosts Xingkailiu Historical Site, which represents the Neolithic fishing civilization of the of Sushen people 6,100 years ago, who are believed to be ancestors of the Manchu. The area surrounding the Reserve is also a place of “Beidahuang” agriculture of the 1950s and 1960s, when soldiers and educated youth were sent to cultivate this wild but fertile land.

Tourism has occurred around the Reserve for many years in scattered locations and 500,000 visitors were drawn from China and abroad in 2000. According to the Management Agency, the number of visitors increased to 930,000 in 2009 with a total tourism income of 2.3 billion RMB (US$0.4 billion). According to the observations of the management agency, most visitors come for the day from nearby cities within the province. Major activities include beach and water activities at the Big Xingkai Lake, wetland exploration at Small Xingkai Lake, bird watching and flower viewing, and visiting Xingkai Lake museum and historical sites. Although a boardwalk trail has been developed, ecotourism is a recent phenomenon in the area and official records of tourist profiles and their behavior are not available and constitute a research need and opportunity.

The 11th Five-Year Plan for Jixi indicates that the Reserve is one of the top three tourism sites in Heilongjiang Province, and tourism development at Xingkai Lake is emphasized in the Heilongjiang Provincial Tourism Plan. In April 2010, Xingkai Lake tourism functional zone was listed as one of the eleven top tourism places in Heilongjiang Province. Ecotourism development at Xingkai Lake is emphasized in the Jixi Eco-city 11th Five Year Plan and in the city’s Tourism Master Plan.

The Reserve was chosen as a case study because of the highly recognized potential for ecotourism among the nine nature reserves in the Sanjiang Plain (Zhang et al. 2008a), the importance of the natural resources, management complexity, the potential conflicts between the local community, resource conservation and economic development (Wang et al. 2011), and because the site was accessible to the researchers.

Findings

Management Structure and Challenges of the Reserve

The Reserve is under the administration of Jixi Municipal Government and supervised by the National Forestry Department and the Heilongjiang Provincial Forestry Department. It is designated for the protection of rare and endangered wildlife and inland water ecosystems and wetlands. The major tasks include protection and restoration, research and monitoring, education and training, tourism and the sustainable use of resources. The Management Agency of the Reserve has twelve departments, including an Administrative Office, Planning and Construction, Tourism Management, Environmental Protection, Research, Education, and Management and Protection department, and eight subordinate management and protection stations (Su et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2011).

Although the ownership of lands ultimately belongs to the government (Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands), the managerial rights of lands around the lake belong to several state farms and collective villages. According to interviews with management officials, segregated land ownership is identified as one of the major management challenges of the Reserve. As shown in Fig. 3, seven parties own land within the Reserve (Su et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2011), two of which are collectively owned and five are nationally owned. According to an official at the management agency, the Management Agency is the only entity that has the rights to the land of its office building and the Small Xingkai Lake. The latter was gained after the Management Agency took over Xingkai Lake Aquaculture Company in 2003. The Management Agency has the management authority of land owned by other parties according to existing rules and regulations but has limited executive power particularly when economic interests are involved (Wang et al. 2011). Discussions and coordination with land owners to seek understanding and reconcile conflicting interests are required for any land use proposal. Not all efforts end up in an agreement. This situation greatly restricts the management and executive power of the Management Agency and the conservation and development of the Reserve. The same official said:

They (other land owners) have their own interests; it is not easy to reach an agreement particularly when economic factors are involved. For example, the state farms own a large piece of land in the nature reserve. They gain high profits through large-scale agricultural production and have high status in the province. They have their own system to operate and manage resulting from their military history. It is very difficult to negotiate with them concerning conservation issues.

Another informant from the Provincial Forestry Department said:

Another management challenge for the Reserve is lack of funding. Although it is a national level nature reserve, the major source of funding comes from local government, which is Jixi Municipal Government. Currently, the funding is unstable and not sufficient to support our day-to-day operation. It restricts the scale of conservation activities we can undertake. So we have several projects pending for more funding in the future.

A pervasive problem among national nature reserves in China is that national status, while raising expectations, does not automatically result in national funding which devolves to the local level. As a result, it is common in China for nature reserves to have insufficient funds to pay the salaries of their personnel. In such situations, there is pressure for the Management Agency to exploit rather than protect resources. It was not surprising that interviewees from the Provincial Forestry Department and the Management Agency also acknowledged the urgency to secure funding to support resource conservation and further development of the Reserve. Ecotourism is, thus, perceived as being in line with the conservation goals of the nature reserve as non-consumptive and with minimal environmental impacts while being potentially a reliable source of funding.

It was also mentioned in interviews that the national agriculture subsidy enhances the income from agricultural activities and supports the continuing development of agriculture surrounding the Reserve. In fact, conflicts exist between the policies of different agencies in both the short and long terms. For example, the conversion of land from agriculture to conservation is hindered by the different subsidies offered by different government departments. The same informant from the Provincial Forestry Department pointed out that:

The national agriculture subsidy in recent years is a very strong incentive for farmers to engage in agriculture and enlarge agricultural land. In comparison, the one-off allowance of converting agricultural land to wetland is small. Some even try to get double subsidy by firstly converting agricultural land to wetland to get the allowance and then returning it back to agricultural land to get the agricultural subsidy. It is very hard for us to control this.

The Local Fishing Community and Ecotourism

Residents of nearby villages do not now work nor live within the boundaries of the Reserve. Small Xingkai Lake is the major fishing area for Xingkai Lake Aquaculture Company, which was established in 1951. Employees of the Company and their families are considered as the community directly associated with the Reserve. Their lives depend on the fish resources of the Reserve and they have cabins on the lake’s bank as temporary working houses that they use during the fishing season. They are located in the core area of the Reserve in an area of great ecological importance.

The company has been under the administration of the Management Agency of the Reserve since 2003. It has 522 employees and an additional associated population of about 1,000, for a total of 1,500 people. With about 80 fishing boats, the company has an annual catch of 1,200 tons and an annual income per person of RMB10,000 (US$1,165). Fishing is the major source of livelihood for employees, supplemented by a small amount of agriculture and weaving, as well as support from national low-income supplements.

The income level is low in the region. Due to the reduction of fish caused by over-fishing, income from fishing is not sufficient to sustain the employees, particularly with rapid increases in fuel prices and the fishing contract. A fisherman indicated that the fishing contract fee in 2011 ranged from RMB 10,000–40,000 (US$1,650–6,650) per boat, which is much higher than the level of RMB 4,000–5,000 (US$650–833) per boat just a couple of years ago. Therefore, with the rising cost of fishing, the net income of residents has dropped. The reduction of fish has also had substantial negative impacts on the habitat and living conditions of bird species.

Management interviews indicated that ecotourism is considered to be a worthy alternative livelihood source that can partially replace fishing and provide long-term employment opportunities for the local community, as tour guides, boat operators, and as service and maintenance staff in tourism facilities. This would reduce fishing, contributing to the recovery of fish and the birds that eat them.

Unstructured interviews with six members of the local fishing community and observation revealed that tourism is currently being developed surrounding the Reserve, with few activities within the Reserve itself. Fishing is still the main source of income for community members within the Reserve (primarily employees of the company), who do not have other effective means to supplement their incomes and are not yet involved in tourism-related activities. As indicated in interviews, the local community recognizes the urgency of their situation caused by over-fishing. They are dissatisfied with their income from fishing, which has been shrinking, and are concerned about the future. Statements from two fishermen illustrated their plight:

The number of big whitefish I can catch is much lower than that of two or three years ago. In addition, it is very difficult to catch big fish now.

Xingkai Lake is a cross-border lake; there is almost no fishing activity on the Russian side. Many fish are hiding on the Russian side. The catch is very low nowadays, which caused the surge of the price of Xingkai Lake whitefish here… People have been caught because they ventured to fish on the Russian Side.

The situation contrasts with the large fish and catches that are displayed in the faded photographs in nearby hotels.

In terms of their perceptions about ecotourism and participation, all interviewees had a positive attitude toward ecotourism; and they are willing to participate to increase their income and living standards. However, without any prior knowledge and experience of tourism business, they do not know how to get involved, how much it will cost and how they might benefit. Interviewees expressed hope that the government or the management agency could help them to start up and benefit from ecotourism.

Therefore, due to the experiential and financial constraints of the local fishing community and the land ownership structure, community involvement in ecotourism at the Reserve requires the government and the Management Agency to play key roles in directing ecotourism development and providing financial and structural support to facilitate the shift of livelihoods from fishing to tourism.

Assessment of Ecotourism at the Reserve

Based on the presence of high-quality natural resources, location, and government and management support, the Reserve has the potential to provide quality ecotourism experiences. Observation and interviews indicated that tourism is at the initial development stage and is primarily concentrated on Big Xingkai Lake beach, Small Xingkai Lake, and the Lake bank. Special resources, such as birds, have not been fully valued for tourism. Resources typically used for tourism, such as swimming and beach activities, contribute little to conservation and community development. Factors, such as the short tourist season and land ownership, pose challenges to the further development of ecotourism in the Reserve.

Based on the application of Ross and Wall’s framework (1999a, b), it is identified that synergistic relationships between tourism, environment, and community have yet to be established (Fig. 4). The Management Agency of the Reserve has been effectively monitoring and preserving flora and fauna in the Reserve through environmental protection, research, and operational specialization. The education division manages Xingkai Lake Museum beside Small Xingkai Lake and is responsible for the environmental education of tourists and the community. The division of the nature reserve into a core protection zone, buffer zone, and experimental zone, as is standard practice for the national nature reserves in China, facilitates resource conservation and management of the resources and their uses. Local communities are mainly engaged in agriculture and fishing, but they have not participated effectively in resource conservation activities. Current management and regulation of tourism activities and community participation are limited due to the current low level of tourism activities within the Reserve and the divided land ownership structure. With fishing as the primary livelihood, the local fishing community has not been involved in tourism. With the ongoing increase in tourist numbers, Dangbi township, Baipaozi county, Xingkai Lake county, and other counties and villages around Big Xingkai Lake have residents that are involved in tourism, providing accommodation, and catering services through individual or collective operations. However, the quality of tourism infrastructure and services is not high or extensive. Therefore, tourism and community involvement have not yet formed a healthy relationship to achieve mutual benefits.

Ecotourism at the Reserve is still at the initial stage of development. A well-designed boardwalk has been built and provides foot access to an attractive area of wetland for a small fee. A substantial but incongruous structure facilitates lake viewing. There are basic beach and boating facilities, a museum, and several commercial accommodation establishments; however, tourism facilities in the Reserve are rudimentary. Synergistic relationships between the environment, community, and tourism are lacking and will require greater coordination in order to be successful.

Management organizations, management policies, and management operations are summarized in Table 3. First, the Management Agency is the major management body of the Reserve. It is a government agency supervised by Jixi Municipality and the Provincial Forestry Department. Different levels (village and county) of local governments, the state farms, and the aquaculture company are involved in the management of the Reserve due to their share of the land or water property rights. These stakeholders have different goals, interests, and responsibilities when using the land and associated resources. The multi-stakeholder management style and the ambiguity of landownership within the Reserve provide structural difficulties for its management and operation, particularly when mechanisms need to be constructed to share costs and benefits of ecotourism development.

Current policies and regulations focus on the conservation of resources and the management of the community’s use of resources. There is currently no ecotourism plan; and there is a lack of policies or regulations on community involvement either in resource conservation or ecotourism.

In terms of management operations, the Reserve is divided into a core zone, buffer zone, and experimental zone according to Management Regulations of the Reserve and Working Policies of the Management Agency of the Reserve. Economic activities such as ecotourism are only allowed in the experimental zone. The reserve is strictly monitored by the Management Agency, which also regularly monitors the environmental quality in the Reserve, including water, soil and wildlife, particularly for endangered species. Xingkai Lake Museum has been constructed on the edge of Small Xingkai Lake and acts as a platform for wetland education for both visitors and locals. Currently, the museum has few visitors. The public education department is designated by the Management Agency to manage the museum. There are ongoing projects to enhance the exhibition and education programs with local schools, in an effort to increase visitation. There is no entrance fee and the number of tourists is only monitored through sales revenue, as for purchases of souvenir items at the museum and boating services at Small Xingkai Lake. Both are operated by the Management Agency. No other data on visitors are available. Most catering and accommodation are provided outside of the Reserve and current tourism service provision is limited.

Despite the fact that the desired synergistic relationship is not yet achieved, the high-quality natural resources, the commitment of the Management Agency, and the needs of the local community for an alternative livelihood ensure the potential of further ecotourism development at Xingkai Lake. The missing links between tourism, environment, and community need to be constructed systematically and a multi-stakeholder development approach should be adopted that recognizes the diverse needs and expectations of management bodies, landowners, and community members.

Discussion

Xingkai Lake National Nature Reserve

Due to its rich and spectacular biodiversity and natural resources, the potential to provide quality nature experiences in the Reserve is high and tourism development is occurring. As a new resource use, ecotourism at the Reserve could become an effective supplementary or alternative livelihood strategy for the local fishing community, partially replacing the existing resource consumptive and declining fishing activity. Ecotourism also has the potential to support environmental conservation, counteracting the conversion of wetlands to agriculture, promoting the restoration of fish and bird species, and enhancing public education regarding resource use, and conservation. However, current relationships between the community, resources, and tourism have not facilitated the mutual benefits necessary for successful ecotourism. The link between tourism and community is particularly weak in both directions. Environment and resources have been supporting both tourism and the community without reciprocal sustaining inputs from either.

The multi-stakeholder management style and the complexity of landownership within the Reserve provide structural difficulties for its management and operation. Ideally, land ownership, particularly the right to use and manage these areas, should be unified under the Management Agency to reduce the number of stakeholders that are involved and simplify the management structure. However, this may require macro-level institutional reform from the central government. Currently, collaboration between different land owners, both national and collective, should be enhanced through joint planning and monitoring activities, due to the importance of connectivity and integration in managing multi-tenure protected areas (Fitzsimons and Wescott 2008 a, 2008b). Findings from this research recommend that information be exchanged regularly to enhance mutual understanding. A responsibility and benefit sharing scheme should be established among all stakeholders of the Reserve. Government intervention and support at provincial or even national level are critical to the establishment of such arrangements.

Furthermore, as current tourism activities are not confined within the boundary of the Reserve, connections should be forged in ecotourism planning and operation between the Reserve and nearby counties and villages to ensure consistency in management, service standards, and experiences offered to tourists. Therefore, it is suggested that an ecotourism network be set up with representatives from each stakeholder group to act as an intermediary in coordinating ecotourism planning and monitoring operations to safeguard service standards and work toward equilibrium in costs and benefits among stakeholders in the area. Again, government intervention is critical in the establishment and operation of such a network.

Findings from this study also identified the lack of appropriate policies and plans to support potential synergistic relationships. Despite the regular monitoring of the environment, there is little monitoring and management of tourism activities and community participation in ecotourism and conservation. Therefore, a comprehensive ecotourism plan is needed. Suitable activities and areas for ecotourism development should be outlined. An ecotourism management plan and a community participation plan should be included. The former should manage and monitor the scale of development and tourism impacts with a focus on long-term benefits rather than short-term income. The later should identify potential types of participation, number of positions, and required capacity for participation.

Current community involvement is low mainly due to the lack of a participation mechanism and the limited communication that occurs between the management and local residents. Economic benefits (employment opportunities and income) and environmental benefits (ecological restoration and financial support to conservation) are given higher priority by the governments, the Management Agency and the community. Little attention is given to the potential social and cultural benefits to the community from ecotourism. Community members hold positive attitudes toward ecotourism and are interested in participation. However, due to the inexperience and financial limitations of the community, the governments and the Management Agency must take the leading role in managing the direction and scale of ecotourism development and actively foster community participation. This is especially the case in China where the support of government is frequently a prerequisite to action.

It is recommended that community organizations that can bridge the current gap between management and the community should be established, such as the workers’ union and village committee (Yang et al. 2009; Su and Wall 2014). These organizations are rooted in the community and have the ability to affect management decisions as shown in the case of Mutianyu Great Wall in Beijing (Su and Wall 2014) and can be used as the channel for information dissemination and community consultation.

Various kinds of participation mechanisms can be established to set up a platform for community participation. Preferential policies safeguarding privileged rights of community members could be set up to support local participation and secure local benefits. According to research conducted by Su and Wall (2014), Mutianyu Village residents are granted the exclusive right to do business at Mutianyu Great Wall in Beijing. They also enjoy income tax release and easy access to apply for business licenses. These measures have ensured that local people receive economic benefits and enhance local satisfaction. Moreover, on-site employment position allocation to community households, financial compensation for restricted use of resources, and financial support to start or sustain tourism business are widely used in various protected areas in China, including Mutianyu Great Wall and Mount Sanqingshan World Heritage Site in Jiangxi Province. As identified by the first author, each family of Shangxikeng village at Mount Sanqingshan is allocated with employment positions at the management agency. In addition, family hotel businesses are supported through funding from the management agency for the construction and decoration of new houses in the relocated village site. Additionally, many rural communities in China rely on family income to start tourism businesses due to their unfamiliarity with the banking system (Su and Wall, 2012, 2014). Thus, the provision of easy access to bank loans and other financial tools that offer low-interest loans would effectively support community business start-ups at Xingkai Lake. In addition, ecotourism education and training programs can be organized to enhance the local capacity to engage in ecotourism and conservation, such as language training as at Mutianyu (Su and Wall 2014), agro-technical training, biodiversity training, and service training or tour guide training.

To deal with the lack of tourist information at Xingkai Lake, research on tourists should be conducted to acquire detailed information of their profile, behavior, and perceptions. This is critical information for ecotourism planning and management. It can also inform the development of links between tourist behavior and community benefits.

Broader Implications on Protected Area Management in China

The Sanjiang Plain, of which the Reserve is a part, is an important agricultural base in China that contributes in an important way to national food security. The Sanjaing Plain also hosts a large area of wetlands, an important indicator of regional environmental quality (Zhang et al. 2008a, b). Since the national agricultural subsidy far outweighs the financial support for wetland conservation, agricultural development is greatly encouraged and wetland conservation is inhibited. Large-scale development of agriculture has seriously affected the quality and quantity of water resources and threatens the size and quality of wetlands on the Sanjiang Plain (Yan et al. 2006). Both agricultural and wetland policies have their own independent rationales. However, both sets of policies are applicable in the Sanjiang Plain, leading to critical issues in regional development at the national policy level, which are hard to reconcile at the local level. Central government should address the current policy contradictions. The situation points to difficulties in cross-sector policy making leading to challenges in implementing national policies at the local level.

This study reflects the widespread structural issue of protected area management in China, caused by the multi-tenure management structure and the ambiguity of landownership, and its impacts on resource conservation and community involvement. The establishment of a specified department in the central government for protected area management is proposed by many scholars to streamline management (Su 2004; Wang et al. 2006; Zhou and Wen 2006; Xia et al. 2009). Unified ownership and management are likely to be beneficial for long-term environmental, economic, and social sustainability (Cheng and Wang 2010), so national policies should be established to unify the use and management rights of protected areas to their management agencies through a variety of land ownership transfers and compensation measures suitable to local situations (Zhou and Wen 2006). A comprehensive legal system with greater legal power should then be established to support institutional reform and safeguard the use and conservation of protected areas (Wang et al. 2006; Cheng and Wang 2010). Institutional change, the unification of land ownership, and modification of the legal system will help to resolve the structural problems of protected area management in China.

Furthermore, nature reserves in China, including those with national status, are not guaranteed funding by the central government and rely heavily on the local government’s financial allocations. Uncertainty in the amount and timing of government funding restricts the scale of resources conservation (Su et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2011). To deal with this situation, the central government may work toward the development of a performance-based funding scheme to supply basic funding for the national level protected areas that meet their conservation requirements. At the same time, protected areas should try to diversify funding sources (Wang et al. 2006), seeking funding opportunities from non-governmental organizations or relevant foundations. Most importantly, opportunities need to be identified to generate revenues in ways that are compatible with conservation goals. Ecotourism, through support for the appreciation and protection of nature and the sustainable use of resources, is seen as being an inevitable choice for the development of protected areas. The relatively undisturbed natural environment at protected areas can constitute a high-quality tourist attraction. Ecotourism income can provide funding for resource preservation at a low environmental cost.

Communities at most protected areas have long been engaged in resource dependent and consumptive livelihood methods, such as agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, and hunting. Protected area designation commonly results in restrictions on the types and scale of resource use, directly affecting local incomes. Livelihoods may be lost, with or without compensation (Wang, 2010). One-time financial compensation can only be satisfactory in the short term. Alternative livelihood strategies that are in line with the objectives for protected areas are needed for long-term community development. Possessing knowledge and experience of the local environment and culture, local residents have the advantage and locational convenience to participate in ecotourism and conservation, which has the potential to move the livelihood system in a sustainable direction by enhancing local living standards and generating public support for conservation.

Conclusions

It is dangerous to generalize from the results of one case study. However, the literature suggests that the situation of Xingkai Lake is typical of most protected areas in China and elsewhere in the world, particularly where there are multiple stakeholders and there is not a history of public involvement in decision making. However, the situation of Xingkai Lake may be more complex than the most because of the complex land tenure system and the international jurisdiction over the lake on which the reserve is located, although the latter has yet to receive much attention among policymakers.

Through analysis and assessment of ecotourism development and community participation at the Reserve, the potential importance of ecotourism in the development of protected areas and the community has been confirmed. Ecotourism is capable of protecting the environment, improving the living standards of local residents, and promoting local economic development. However, for this to occur, careful planning and management are required. The Ross and Wall (1999a, b) framework and the assessment parameters (Table 1) have proven to be effective in guiding the assessment of the status of ecotourism in a protected area and highlighting areas requiring improvement. In particular, as a useful supplement to Ross and Wall’s framework (1999a, b), the list of parameters (Table 1) for assessing the management status of ecotourism from three key perspectives is a useful addition and is especially pertinent when different stakeholders and management bodies are involved.

Current relationships among tourism, community, and resources are weak at the Reserve. The livelihood of the local community depends on extractive resource uses. Due to the management structure, power distribution, land ownership complexity, and the limited competence of the local community, the governments and management agency should take the initiative to facilitate community participation in ecotourism at the protected area. Few other organizations or individuals may be in a position to contribute or even take a leadership role.

Key to fully comprehending the complexity of the Reserve is to first understand that Xingkai Lake is still in the early stages of ecotourism development. The issues and challenges at the Reserve are representative of those occurring at many nature reserves in China (Stone and Wall 2003; Xu et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2013) and in many other developing country contexts (Spiteri and Nepal 2006; Stronza and Pêgas 2008). Thus, the research results and the assessment framework could have implications for the management and tourism development of other nature reserves in China and other developing country cases. However, the future of Xingkai Lake and, thus, the nature reserve, is not entirely within the Chinese hands for the international border with Russia transects the lake. Much like the Great Lakes in North America, a shared international responsibility exists, further complicating the jurisdictional and decision-making context. However, to date, only limited progress appears to have been made in cross-border water management between China and Russia. Further research could explore the potential and feasibility of enhanced cross-border collaboration between China and Russia in resources management, protection and utilization of water and wetlands, and ecotourism development.

References

Bao JG, Sun JX (2006) A contrastive study on the difference in community participation in tourism between China and the West. Acta Geogr Sin 4:401–413 (in Chinese)

Biba S (2014) China cooperates with Central Asia over shared rivers. China dialogue, 24 February. https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/6741-China-cooperates-with-Central-Asia-over-shared-rivers-

Boo E (1993) Ecotourism planning in protected areas. In: Lindberg K, Hawkins D (eds) Ecotourism: a guide for planners and managers. The Ecotourism Society, North Bennington, pp 15–54

Brandon K (1993) Basic steps toward encouraging local participation in nature tourism projects. In: Lindberg K, Hawkins D (eds) Ecotourism: a guide for planners and managers. The Ecotourism Society, North Bennington, pp 134–151

Buckley R, Cater C, Zhong L, Chen T (2008) SHENGTAI LUYOU: Cross-Cultural comparison in ecotourism. Ann Tourism Res 35(4):945–968

Ceballos-Lascurain H (1993) Ecotourism as a worldwide phenomenon. In: Lindberg K, Hawkins D (eds) Ecotourism: a guide for planners and managers. The Ecotourism Society, North Bennington, pp 12–14

Chen JM (2006) On research analysis and suggestions of development of community-based ecotourism. Probl For Econ 26(6):558–561 (in Chinese)

Chen WJ, Law SC (2012) What is the value of eco-tourism? An evaluation of forested trails for community residents and visitors. Tourism Econ 18(4):871–885

Cheng L, Wang TZ (2010) Analysis on the Future Policy Tendency of Ecotourism Management Based on the Appropriation of Benefits in Western China. Soc Nat Resour 23(2):128–145

Christopoulou OG, Tsachalidis E (2004) Conservation policies for protected areas (wetland) in Greece: a survey of Local Residents. Water Air Soil Pollut Focus 4:445–457

Cui Q, Xu H, Wall G (2012) A cultural perspective on wildlife tourism in China. Tourism Recreat Res 37(1):27–36

Davis D, Allen J, Consenza RM (1988) Segmenting local residents by their attitudes, interests and opinions toward tourism. J Travel Res 27(2):2–8

Deng J, Selin S (2012) Application of the Delphi method to ecotourism destination evaluations: a rejoinder to Brian Garrod. J Ecotourism 11(3):224–229

Deng B, Wu BH (2006) Progress of community-based ecotourism research overseas. Tourism Tribune 21(4):84–88 (in Chinese)

Deng J, Benderb M, Selina S (2011) Development of a point evaluation system for ecotourism destinations: a Delphi method. J Ecotourism 10(1):77–85

Donohoe HM, Lu X (2009) Universal tenets or diametrical differences? An analysis of ecotourism definitions from China and abroad. Int J Tourism Res 11(4):357–372

Eagles PFJ (2009) Governance of recreation and tourism partnerships in parks and protected areas. J Sustain Tourism 17(2):231–248

Fitzsimons JA, Wescott G (2008a) Evolving governance arrangements in multi-tenure reserve networks. Environ Conserv 35(1):5–7

Fitzsimons JA, Wescott G (2008b) The role of Multi-tenure reserve networks in improving reserve design and connectivity. Landsc Urban Plan 85:163–173

Foucat, V. S. A. (2002). Community-based ecotourism management moving towards sustainability, in Ventanilla, Oaxaca, Mexico. Ocean Coast Manage 45:511–529

Garrod B (2012) Applying the Delphi method in an ecotourism context: a response to Deng et al.’s ‘Development of a point evaluation system for ecotourism destinations: a Delphi method’. J Ecotourism. 11(3):219–223

Giannecchini J (1993) Ecotourism: new partners, new relationships. Conserv Biol 70(2):429–432

Gössling S (1999) Ecotourism: a means to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem functions? Ecol Econ 29:303–320

Hamilton L (2001) International transboundary cooperation: some best practice guidelines. In: Harmon D (ed) Crossing boundaries in park management: Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Research and Resource Management in Parks and on Public Lands. The George Wright Society, Hancock, http://www.georgewright.org/2001proc.html. Accessed 1 Feb 2014

Han NY (2000) A policy study on sustainable management for China’s nature reserves. J Nat Resour 15(3):201–207 (in Chinese)

Honey M (1999) Ecotourism and sustainable development: who owns paradise?. Island Press, Washington

Hou GL, Huang ZF, Zhang XL (2007) Community participatory ecotourism development model of Yancheng coastal and marine wetland in Jiangsu province. Hum Geogr 22(6):124–128 (in Chinese)

Ioannides I, Nielsen PA, Billing P (2006) Transboundary Collaboration in Tourism: the Case of the Bothnian Arc. Tourism Geogr 8(2):122–142

Kiss A (2004) Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds? Trends Ecol Evol 19(5):231–237

Langholz J (1999) Exploring the effects of alternative income opportunities on rainforest use. Soc Nat Resour 12(2):139–150

Lee CK, Mjelde JW (2007) Valuation of ecotourism resources using a contingent valuation method: the case of the Korean DMZ. Ecol Econ 63(2–3):511–520

Li J (2005) A demonstrative study on the rural community employment and the distribution of tourism income in the development of ecotourism in China’s western regions - taking the rural community in Shaanxi Taibaishan National Park as an example. Tourism Tribune 20(3):18–22 (in Chinese)

Li WJ, Han NY (2001) Ecotourism Management in China’s Nature Reserves. R Swed Acad Sci 30(1):62–63

Lian YL (2005) Opinion of alternative pattern of ecotourism. J Sichuan Norm Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 32(1):35–40 (in Chinese)

Lim C, Mcaleer M (2005) Ecologically sustainable tourism management. Environ Model Softw 20:1431–1438

Liu CY, Li JS, Pechacek P (2013) Current trends of ecotourism I China’s nature reserves: a review of the Chinese literature. Tourism Manage Perspect 1:16–24

Malek-Zadeh E (1996) The ecotourism equation: measuring the impacts. Yale School of Forestry, New Haven

Mason SA, Moore SA (1998) Using the Sorensen Network to Assess the Potential Effects of Ecotourism on Two Australian Marine Environments. J Sustain Tourism 6(2):143–154

Monavari M, Fard SMB (2011) Application of network method as a tool for integrating biodiversity values in environmental impact assessment. Environ Monit Assess 172(1–4):145–156

Murphy PE (1985) Tourism: a community approach. Methuen, New York

Nyaupane GP, Thapa B (2004) Evaluation of ecotourism: a comparative assessment in the annapurna conservation area project, Nepal. J Ecotourism 3(1):20–45

Ross S, Wall G (1999a) Evaluating ecotourism: the case of North Sulawasi, Indonesia. Tourism Manage 20(6):673–682

Ross S, Wall G (1999b) Ecotourism: towards congruence between theory and practice. Tourism Manage 20(1):123–132

Russell A (2007) Anthropology and ecotourism in European wetlands. Tourist Stud 7:225–244

Salafsky N, Wollenberg E (2000) Linking livelihoods and conservation: a conceptual framework and scale for assessing the integration of human needs and biodiversity. World Dev 28(8):1421–1438

Scheyvens R (2003) Local involvement in managing tourism. In: Singh S, Timothy DJ, Dowling RK (eds) Tourism in destination communities. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, pp 229–252

SEPA, China Environmental Statistics Bulletin 2012 (2013) State Environmental Protection Administration, Beijing (in Chinese)

Shams A (2012) Towards a quantification model: the accountability of the for-profit and non-profit organizations in the High Mountains of Sinai Peninsula. Int J Tourism Anthropol 2(3):185–212

Simmons DG (1994) Community participation in tourism planning. Tourism Manage 15:98–108

Spiteri A, Nepal SK (2006) Incentive-based conservation programs in developing countries: a review of some key issues and suggestions for improvements. Environ Manage 37(1):1–14

Stone M, Wall G (2003) Ecotourism and community development: case studies from Hainan, China. Environ Manage 33(1):12–24

Stronza A, Pêgas F (2008) Ecotourism and conservation: two cases from Brazil and Peru. Hum Dimens Wildl 13:263–279

Su Y (2004) Countermeasures for improving management of natural reserves in China. Green China 18:25–28 (in Chinese)

Su MM, Wall G (2011) Chinese research on world heritage tourism. Asia Pac J Tourism Res 16(1):75–88

Su MM, Wall G (2012) Global–local relationships and governance issues at the Great Wall World Heritage Site, China. J Sustain Tourism 20(8):1067–1086

Su MM, Wall G (2014) Community participation in tourism at a world heritage site: Mutianyu Great Wall, Beijing, China. Int J Tourism Res 16:146–156

Su JB, Liu BL, Ma JZ (2008) Current situation and corresponding countermeasures for management of Xingkai Lake National Nature Reserve. J Northeast For Univ 5:60–62 (in Chinese)

Timothy DJ (2000) Tourism and international parks. In: Butler RW, Boyd SW (eds) Tourism and National parks: issued and implications. Wiley, Chichester, pp 263–282

Timothy DJ, Teye VB (2004) Political boundaries and regional cooperation in tourism. In: Lew A et al (eds) Geography companion book in tourism. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 584–595

Tsaur SH, Lin YC, Lin JH (2006) Evaluating ecotourism sustainability from the integrated perspective of resource, community and tourism. Tourism Manage 27(4):640–653

Wall G (1996) Ecotourism: change, impacts and opportunities. In: Malek-Zadeh E (ed) The ecotourism equation: measuring the impact. Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, pp 206–216

Wall G (1997) Is Ecotourism sustainable? Environ Manage 21(4):483–491

Wang Y (2010) Study on community participation mechanism in ecotourism development—a case study in Yancheng Wetland Nature Reserve. Resour Dev Mark 26(12):1138–1147 (in Chinese)

Wang JF, Liu Y, Guo HC (2006) The Management of its nature reserve in New Zealand and its inspiration on China. Environ Protect 5:75–78 (in Chinese)

Wang FK, Piao DX, Liu HJ (2011) Current status of management of Xingkai Lake Nature Reserve. Wetl Sci Manage 7(2):32–34 (in Chinese)

Wanglang National Nature Reserve official website (2014) http://www.wanglang.com/index.asp. Accessed 1 Mar 2014

Weaver DB (2001) The encyclopedia of ecotourism. CAB International, Wallingford

West P (2006) Conservation is our governance now: the politics of ecology in Papua New Guinea. Duke University Press, London

Wu HZ, Hong CM, Zhong LS (2005) A study on the residents’ perception and attitude towards ecotourism in Penghu Islands. Tourism Tribune 20(1):57–62 (in Chinese)

Wunder S (1999) Promoting forest conservation through ecotourism income? A case study from the Ecuadorian Amazon region. CIFOR, Bogor

Wunder S (2000) Ecotourism and economic incentives—an empirical approach. Ecol Econ 32:465–479

Xia SM, Yan XW, Xi K, Liang XY (2009) Analysis of the management system of nature reserves in China. J Zhejiang For Coll 26(1):127–131 (in Chinese)

Xu CX (2005) On woodland dweller knowing situation for ecological tourism development with a case of Jindong in Hu’nan. Syst Sci Compr Stud Agric 21(3):190–192 (in Chinese)

Xu FF (2006) Evaluating sustainability of ecotourism based on community—case study of Red Crowned Crane Wetland Nature Reserve, Jiangsu. J Nanjing Univ Finance Econ 6:52–64 (in Chinese)

Xu JY, Lü YH, Chen LD, Liu Y (2009) Contribution of tourism development to protected area management: local stakeholder perspectives. Int J Sustainable Dev World Ecol 16(1):30–36

Yan D, Xia J, Wang LX, Li YC (2006) Assessment of the coordinated development level between grain production in Heilongjiang province and wetland in Sanjiang Plain. J Nat Resour 21(1):73–78 (in Chinese)

Yang YY, Yan LJ, Shi MF, Wei BQ (2009) Developing a community participation platform for ecotourism in poor areas: a Case Study Oil Taihuyuan Scenic Area in Zhejiang Province. J Beijing For Univ (Soc Sci) 8(3):50–53

Zeppel H (2006) Ecotourism: sustainable development and management. CABI, Wallingford