Abstract

Participatory research in which experts and non-experts are co-researchers in addressing local concerns (also known as participatory action research or community-based research) can be a valuable approach for dealing with the uncertainty of social–ecological systems because it fosters learning among stakeholders and co-production of knowledge. Despite its increased application in the context of natural resources and environmental management, evaluation of participatory research has received little attention. The objectives of this research were to define criteria to evaluate participatory research processes and outcomes, from the literature on participation evaluation, and to apply them in a case study in an artisanal fishery in coastal Uruguay. Process evaluation criteria (e.g., problem to be addressed of key interest to local and additional stakeholders; involvement of interested stakeholder groups in every research stage; collective decision making through deliberation; and adaptability through iterative cycles) should be considered as conditions to promote empowering participatory research. Our research contributes to knowledge on evaluation of participatory research, while also providing evidence of the positive outcomes of this approach, such as co-production of knowledge, learning, strengthened social networks, and conflict resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social–ecological systems in which there is a two-way feedback relationship between the human components and the ecosystem are complex; they present non-linearity, uncertainty, and multiple scales (Berkes et al. 2003). These features, together with the feedback-driven changes that these systems experience, make them unpredictable. This unpredictability highlights the importance of iterative events of “learning by doing” (typical of adaptive management), in order to adapt the decision-making processes according to the variability of the system (Berkes 2009). This new management perspective emerged concomitantly with an alternative view of science as not authoritarian, value-free, or universal (Funtowicz and Ravetz 2000; Ludwig 2001; Bocking 2004), which assumes that user participation may help overcome the present crisis of natural resources management, and solve complex environmental problems (Walker and Daniels 2001; Armitage et al. 2007). One of the arguments to support resource user and public participation states that not considering their judgment and opinion is against democratic values (Fiorino 1990). Non-experts’ and experts’ judgments are equally important, and the combination of both may lead to a better governance of natural resources. In this regard, it is widely recognized that local and traditional knowledge about resources, climate, and ecosystem dynamics can provide unique information about local conditions and potentially complement scientific knowledge (if not intertwined during knowledge co-production) for natural resource and environmental management (Armitage et al. 2011).

Participatory research can be seen as a way of fostering learning and co-production of knowledge, both tending to deal with uncertainty, augmenting the resilience of social–ecological systems. Participatory research, whose origin goes back to the 1970s, is designed to support local people in responding to their own needs (Fals Borda 1987; Cornwall and Jewkes 1995; Wilmsen et al. 2008; Chevalier and Buckles 2013). It offers one way to create power-sharing relationships between researchers and communities, to develop locally appropriate resource management strategies, and to strengthen social capital (Arnold and Fernandez-Gimenez 2007). Nevertheless, it is common to find different modes of participatory research according to the degree of participation or the relationship between the researcher and the community. These modes have been represented by varied typologies, such as “contractual, consultative, collaborative, and collegiate” (Biggs 1989), and “co-option, compliance, consultation, cooperation, and co-learning” (Kindon 2008). In one extreme of the continuum, the researcher designs and carries out the research; community representatives are chosen but largely uninvolved; and there is no real power sharing. In the other extreme (empowering participatory research), the researcher and the community share knowledge, create new understanding, and work together to form action plans, with clear power sharing (Kindon 2008). This mode of participatory research (i.e., empowering) has been difficult to achieve (Cornwall and Jewkes 1995; Arnold and Fernandez-Gimenez 2007).

Even though participatory research has been increasingly found in contexts of natural resources and environmental management (Hartley and Robertson 2006; Wilmsen et al. 2008; Shirk et al. 2012), its evaluation or systematic analysis has been poorly addressed. Given that a key element of participatory research is continuous learning and adaptation (Kemmis and McTaggart 2005), formative evaluation throughout the process would help improve participatory research practice. In addition, systematic evaluation of participatory research projects is needed to assess whether the claimed benefits of this approach are achieved in practice (Blackstock et al. 2007). An important contribution in this direction was made by Blackstock et al. (2007), who proposed a framework to guide the design of evaluation of participatory research and provided a review of evaluation criteria from the literature.

While aiming to contribute to filling this gap about the evaluation of this approach, the objectives of our research were to define criteria to evaluate participatory research processes and outcomes (from the participation literature), and to apply them in a case study. Our case study was a participatory research initiative that has been taking place since 2011 in an artisanal fishery in Piriápolis (coastal Uruguay), involving multiple stakeholders. Using Biggs’ (1989) modes of participation, this case could be best defined as collegiate because scientists, fishers, a fisheries manager, and NGO representatives worked together as colleagues with different skills to offer, in a process of mutual learning, generating knowledge on constraints of mutual importance (Cambell and Salagrama 2001). By putting seventeen evaluation criteria into practice, the case study intended to contribute to the development and evaluation of additional participatory research initiatives, rather than focusing on assessing the degree of achievement in the Piriápolis case. The formative evaluation was performed during the first eleven months of this participatory research project; the multi-stakeholder group has continued working, learning, and adapting since then. After describing in more detail the case study and data collection procedures, the paper proceeds by defining nine evaluation criteria related to the process of participatory research and eight criteria related to its outcomes. We then apply these criteria to the Piriápolis case. Finally, the findings are discussed in light of some opportunities and challenges for a wider use of the participatory research approach.

Methods

Case Study Description: Participatory Research in Piriápolis Artisanal Fishery (Uruguay)

This research was based on a case study (Yin 1994) in the artisanal fishery in Piriápolis (Río de la Plata coast, Uruguay; see Trimble and Johnson 2013), where a participatory research project involving multiple stakeholders was initiated by the lead author as part of her doctoral thesis about barriers and opportunities for artisanal fisheries co-management (Trimble 2013). During the initial stage of the participatory research project (March 2011), fishers decided that it should address the problem of sea lions, which feed from gillnets and long-lines, damaging them. Afterward, the lead author invited government, academics, and non-governmental stakeholders to participate. Since May 2011, stakeholders have been meeting regularly in Piriápolis during workshops, generally in a monthly basis, to address collectively local concerns of the fishery. These workshops have been facilitated by the lead author and an undergraduate student, who represented the “organization team” (for a description of their roles see Trimble and Berkes 2013). Of all the participatory research activities, the co-author only participated in the first workshop, where she provided assistance with the facilitation. Workshop costs in 2011, including travel and food, were funded by the lead author’s research budget from the Centre for Community-Based Resource Management (Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba). Stakeholders have been volunteering their time to participate. Since 2012 the group has been receiving its own funding from different sources.

Fifteen participants from four stakeholder groups were committed to the participatory research initiative in 2011: fishers (n = 7; 4–10 participated in different stages), artisanal fisheries manager (DINARA-National Directorate of Aquatic Resources, n = 1), university scientists (n = 5), and local NGO representatives (n = 2). For all of them, this was the first involvement in a participatory research experience. The name “POPA – Por la Pesca Artesanal en Piriápolis” (For Artisanal Fisheries in Piriápolis) was chosen through a brainstorming exercise. Despite the common interest of the four stakeholder groups on “artisanal fisheries”, conflicts among them were evident. The most relevant in terms of resources management was the conflict between fishers and the fisheries agency (DINARA), which has traditionally focused on the development of the large-scale fisheries sector. Only recently has DINARA started a transition toward more participatory modes of artisanal fisheries governance in certain regions of the country (Trimble and Berkes 2013). Conflicts between fishers and scientists or conservation-oriented NGOs were also present; fishers tended to see the latter as the sea lion protectors and scientists/NGO representatives tended to see fishers as the “villains” against sea lions. Four of the participating scientists and one NGO representative had participated in previous meetings where dialogue with fishers was chaotic and disrespectful, mainly due to unskilled facilitators, as they explained.

Data Collection for Evaluating the Participatory Research Case

Case studies and a variety of qualitative methods are often used in evaluation research (Yin 1994). An evaluation of the participatory research initiative in Piriápolis was conducted throughout the process with the purpose of learning and improving, and the ultimate goal of informing future research work (Blackstock et al. 2007). This process evaluation, which looked at the operation of the participatory research initiative and analyzed how outcomes were produced, is also called formative evaluation. Our evaluation also had elements of an ex post or summative evaluation because the outcomes from the participatory research case until a certain period were analyzed, although the project continued afterward. Seventeen evaluation criteria were used: nine related to the participatory research process and eight to its outcomes. These criteria were taken from some of the literature on public participation evaluation (Rowe and Frewer 2000; Stephens and Berner 2011); a key article about participatory research evaluation which comprised an extensive review (Blackstock et al. 2007); and general literature on the characteristics and expected impacts of participatory research (e.g., Reason 1994; Cornwall and Jewkes 1995; Kemmis and McTaggart 2005; Kindon 2008). The latter sources were indeed useful for the development of the participatory research initiative in Piriápolis. Table 1 shows the 17 criteria analyzed (which are described in the next section) and similar evaluation criteria found in the literature.Footnote 1 The criteria to evaluate public participation in decision-making contexts (e.g., consensus conferences and public hearings), such as those proposed by Rowe and Frewer (2000), were adapted to evaluate participatory research (which involves public participation in knowledge generation but not necessarily in policy making). It should be noted that the criteria to evaluate public participation in the context of policy decision making originated from different conceptual streams, such as procedural justice, theory of democracy, and collaborative learning (Webler and Tuler 2002). Even though evaluation criteria were categorized as process or outcomes (as found in the evaluation literature), some outcome criteria (e.g., learning, co-production of knowledge, and strengthened social networks) can be evaluated throughout the process as well. In fact, Blackstock et al. (2007) suggested that depending on the purpose of the evaluation, the same criteria could be used to measure both process and outcomes.

Given that the foundational nature of participatory research involves continuous learning and adaptation, a permanent evaluation is recommended. The time period evaluated in the Piriápolis case was from March 2011 (pre-stage; problem definition; and convening of stakeholders) to April 2012, when the lead author had to start the data analysis phase for her dissertation. Nonetheless, her observations of group activities continued afterward because she stayed involved in POPA.Footnote 2 As suggested in the evaluation literature (e.g., Bellamy et al. 2001; Rowe et al. 2004; Blackstock et al. 2007), data for this research were gathered from a variety of participating stakeholders, through combining recorded data (e.g., field notes) and reported data (e.g., interviews), in order to capture the diversity of views. As opposed to conventional evaluation (positivist or post-positivist paradigms) which does not contemplate direct work with stakeholders and their constructions (Guba and Lincoln 1989), the constructivist approach to evaluation, in which stakeholders’ claims, concerns, and perceptions are contemplated, is compatible with the increased trend of involving the public and resource users in natural resources and environmental management (Plummer and Armitage 2007). In the Piriápolis case, data collection took place by means of individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews (Dunn 2008) with all participants; participant observation (Bernard 2006) during workshops, group/subgroup meetings, and additional group activities; and informal conversations with participants. All these methods have been identified as appropriate to collect data about content and process, and using a plurality of methods helps secure the validity of the findings (Bernard 2006). Triangulation was indeed the main strategy used to ensure the validity of the evaluation. Triangulation of data methods (i.e., comparing data collected by various means, such as interviews and participant observation) and triangulation of data sources (i.e., interviewing different people) were of particular relevance (Krefting 1991). In addition, member checking of findings (a strategy that ensures that the researcher has accurately translated the participants’ viewpoints into data) was conducted to ensure accuracy and validity (Morse et al. 2002).

Most interviews were audio-recorded; written questionnaires were only used when interviews could not be scheduled. Out of the 66 individual instances of evaluation with the 15 committed participants (POPA members), nine consisted of written questionnaires. Five other interviews were conducted with individuals who participated only in one workshop (four fishers and one scientist). The number of evaluation instances with each participant varied between 1 and 7 (4 on average) depending on the number of workshops they attended (of a total of nine in 2011) and their time availability for conducting the evaluation. The final interviews with all participants (n = 15) were conducted between February and April 2012, less than 12 months after the first workshop (May 2011). The lead author conducted the interviews with the collaboration of the undergraduate student. As the organization team, they were in permanent contact with participants throughout the entire evaluation period (i.e., on a weekly or daily basis). This extended contact of evaluators with participants, in which the former are immersed in the situation, is particularly suitable for evaluations of process or human behavioral changes (Conley and Moote 2003), and also helps ensure the research validity. The co-author was not involved in data collection but only in the analysis. This is worth mentioning because of the claimed need to find a balance between those who have been involved in the process (with insider understanding) and those who have not been involved (external evaluation) (Blackstock et al. 2007). Interviews’ transcriptions and field notes were coded and analyzed qualitatively (using Atlas.ti software), according to the seventeen evaluation criteria.

Criteria to Evaluate Participatory Research Process and Outcomes

Process Criteria

Problem or Topic to be Addressed of Key Interest to Local and Additional Stakeholders

Participatory research aims at involving stakeholders in looking for solutions to local problems, contributing to their empowerment. Therefore, the origin of a participatory research project needs to be based on a local interest to address a certain problem or improve a specific situation. This criterion has not been found in the literature that we reviewed about evaluation of participatory research, although it is commonly found as a foundational component of this approach. The origin of the process may vary; the topic can either be identified by local stakeholders, who then contact additional stakeholders (e.g., academics, government, and NGOs) to be part of the participatory research initiative, or by external stakeholders who recognize a problem and then assess local stakeholders’ perceptions about it and their interest to participate. In addition to local interest in the selected topic or problem, there must be interest in addressing it by means of participatory research (instead of other means). In spite of who selects the general topic, the different stakeholders should participate in defining the specific problems or research questions to be addressed.

Participation of Interested Stakeholder Groups in the Selected Problem or Topic (Stakeholder Diversity)

Once the problem to be addressed in a participatory research initiative is defined, the involvement of interested stakeholder groups should follow (e.g., academic institutions, governmental organizations, and NGOs, in addition to local people). Improving the discussion of the selected topic by combining multiple understandings and forms of knowledge is one of the key elements of participatory research (i.e., its substantive nature). Stakeholder diversity is sometimes considered within the representativeness criterion (e.g., diversity of views, Blackstock et al. 2007; Stephens and Berner 2011), but we have considered the latter separately.

Participants’ Representativeness

Representation is a criterion found in the literature usually referring to the spread of representation from affected interests, including legitimacy (Rowe and Frewer 2000; Blackstock et al. 2007; Stephens and Berner 2011). This evaluation criterion is particularly relevant when the participatory process is linked to policy decision making (Rowe and Frewer 2000; Trimble et al. 2014). In the case of participatory research, the degree of participants’ representativeness might affect the legitimacy of the outcomes and process, as well as the influence and impacts of the results (two Outcome criteria). In order to favor local stakeholders’ representativeness, it is useful to unravel at a former stage the complexities of local relationships within the community.

Involvement of Interested Stakeholder Groups in Every Research Stage

Participatory research requires that the whole process is developed collectively by participants (as co-researchers), including objectives’ definition, methodology design/planning of activities, data collection/development of activities, analysis, evaluation, and dissemination. This criterion sets one of the most remarkable differences between participatory research and conventional research (i.e., experts’ research) or even research projects which give low degrees of participation to local stakeholders (e.g., when the objective is defined by scientists and the community is asked to assist in data collection). Participatory research requires early and continuous involvement of all interested stakeholder groups in the process of problem solving and knowledge co-production.

Facilitation

The independence criterion, as defined by Rowe and Frewer (2000—lack of bias from whoever is promoting or facilitating the process), advises that no stakeholder group should have more power when decisions are made. However, in a participatory research initiative some stakeholder groups (e.g., experts and government officers) will inherently have more power (Gaventa and Cornwall 2001). The facilitator(s) must acknowledge this power differential, inviting the less powerful groups to participate in discussions in an open manner. The facilitator is in charge of promoting mutual respect and tolerance among participants (e.g., respect toward others’ viewpoints and knowledge) and ensuring that interventions during discussions are balanced—key elements if decisions are to be made collectively. In order to achieve this balanced dialogue between different forms of knowledge, when there is tension or mistrust among participants, it is recommended that the participatory research process is facilitated by someone who is not involved in the selected topic (i.e., a third party; Chevalier and Buckles 2013).

Collective Decision Making Through Deliberation

In participatory research, problem solving is done collaboratively by interested stakeholder groups, and thus decision making throughout the process must be collective. Sharing all participants’ perspectives and evaluating the exposed arguments together should occur before the final step of making decisions. Similar criteria are found in the literature, such as the quality of decision making, referring to the establishment and maintenance of agreed standards for making decisions (Blackstock et al. 2007); or structured decision making, emphasizing appropriate mechanisms for structuring and displaying the decision-making process (Rowe and Frewer 2000).

Appropriate Information Management

Rowe and Frewer (2000) proposed the criterion of resource accessibility for evaluating public participation processes linked to policy making, including information resources (summaries of the pertinent facts), human resources (e.g., access to scientists), material resources (e.g., overhead projectors/whiteboards), and time resources (i.e., sufficient time to make decisions). In participatory research, fulfilling appropriate information management depends on achieving the participation of the main stakeholder groups in the process, which would share information and knowledge with the rest. This information should be of appropriate quality and quantity to the participatory research needs. First, communication among participants needs to overcome the barriers imposed by jargon and technical terms; and second, information from stakeholder groups should be balanced. If a stakeholder group does not participate in the participatory research process, its arguments should be known and considered by participants. Means of communication among participants (when not face-to-face) should be appropriate to participants’ available resources.

Adaptability Through Iterative Cycles of Planning, Acting, Observing, and Reflecting

Participatory research as an iterative process of finding solutions for local problems involves several stages, which can be summarized as follows: planning (e.g., identifying the problem and defining research questions), acting and observing (e.g., defining the study methods, collecting data and information, and analyzing), and reflecting. However, these stages, which Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) conceptualized as part of a spiral of self-reflective cycles, should be guiding principles rather than strict steps to take. In fact, they argued that these stages overlap (Kemmis and McTaggart 2005). Very importantly, adaptability needs to be present during the entire process: both the facilitators and participants should be open to new topics and research questions which may arise while reflecting on actions already taken. Although they might go off the starting point, these new topics can be of interest to the participating stakeholder groups, something that should be ensured.

Cost-Effectiveness of the Process

Understanding the ratio between all possible costs of participatory research processes (e.g., economic costs, time, and effort) and the process’ effectiveness (e.g., perceived benefits and successful actions) is crucial for their applicability and replicability. Blackstock et al. (2007) referred to this criterion as the improvements created through the process in relation to the costs accrued. We argue that it is important to consider, as well, the personal evaluation (or weighing) of efforts and benefits that participants do to decide whether to participate in the process. In other words, what are participants (and their respective organizations) willing to invest and compromise for which achievements? Understanding stakeholders’ evaluation of the cost-effectiveness ratio can be useful for the organization team when trying to fulfill other criteria (e.g., participants’ representativeness). Moreover, the support that the organizations being represented are willing to provide (financial resources, human resources, and infrastructure—i.e., costs), will likely affect the intended participatory research.

Outcome Criteria

Achievement of Objectives

The achievement of objectives at the level of individuals, stakeholder groups, and ideally of the formed group is a key aspect to evaluating participatory research outcomes. This can be a determining factor for stakeholders’ continuing participation and commitment to the process. For example, from the perspective of the academics or experts involved, the quality of the research and scientific results will affect their evaluation of whether the objectives have been achieved. Moreover, considering that the development of shared vision and goals is expected during participatory research (Blackstock et al. 2007), which can be enhanced by the role of the facilitator, the relationship between individual and group objectives should be evaluated as the process progresses.

Outcomes and Process Perceived as Successful

In addition to evaluating the degree to which objectives have been achieved, it is important to evaluate how participants value other outcomes of the participatory research initiative. These will also affect participants’ continuity. As a related criterion, Blackstock et al. (2007) defined ownership of outcomes, referring to whether there is an enduring and widely supported outcome. Furthermore, considering that participatory research success (as opposed to conventional research) depends also on the progress of the process (Kemmis and McTaggart 2005), participants’ evaluation of the process (not just of the outcomes) is needed.

Co-production of Knowledge

This criterion refers to the epistemological foundation of participatory research, which parallels the substantive argument proposed by Fiorino (1990). One of the expected outcomes of participatory research is new knowledge co-produced by a diversity of stakeholders. Knowledge co-production may be defined as “the collaborative process of bringing a plurality of knowledge sources and types together to address a defined problem and build an integrated or systems-understanding of that problem” (Armitage et al. 2011, p. 996).

Learning

In addition to the new knowledge which contributes to understanding or solving a local problem, learning among participants is another key outcome of participatory research. Learning can be analyzed from many lenses. Two criteria proposed by Blackstock et al. (2007) fit our criterion: capacity building (i.e., developing relationships and skills to enable participants to take part in future processes or projects) and social learning, referring to the way that collaboration has changed individual values and behavior, influencing in turn collective culture and norms. The Learning criterion we propose comprises all these aspects and includes learning about the problems addressed given the interaction of different viewpoints and knowledge. The complexities and uncertainties of managing environmental problems highlight the need for stakeholders’ learning and adaptation. Social or collaborative learning should thus be considered not only as a valuable by-product of participation but also as a goal in itself (Lázaro et al. 2013).

Strengthened Social Networks

Another expected outcome of participatory research is improved relationships among stakeholders and the establishment of new connections—in other words, strengthened social networks. Blackstock et al. (2007) referred to the relationships criterion to evaluate issues of social capital by analyzing existing and new social networks, including relationships of trust, reciprocity, and collaboration.

Conflict Resolution

Related to social networks, another criterion to evaluate participatory research outcomes is its capacity to resolve conflicts between stakeholder groups. This criterion refers to conflict abatement among participants and the way in which conflicts were resolved (Blackstock et al. 2007; Stephens and Berner 2011). Moreover, it should be considered how this conflict resolution extends to other stakeholders who have not been involved in the participatory research process.

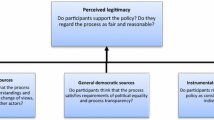

Legitimacy

One expected outcome of participatory research, if process criteria are met, is that its results will be legitimate to all participating stakeholders. Legitimacy, referring to whether the outcomes and process are accepted and seen as valid by stakeholders (Blackstock et al. 2007; Stephens and Berner 2011), can be evaluated both at the internal level (i.e., participants) and the external level (non-participants from the same stakeholder group and others).

Influence and Impacts of the Results

Considering that participatory research results may have real impact on the political decisions made regarding the topics and problems addressed, this needs to be evaluated. This is particularly important given that one of the main problems of participatory processes is that they are perceived as a means to legitimate decisions or as an apparent consultation, creating skepticism among the public (Fiorino 1990). The capacity to influence additional stakeholders who have not participated is also a key factor for the legitimacy and sustainability of participatory research. This is part of the Opportunity to influence criterion by Blackstock et al. (2007), and also related to Recognized impacts, referring to whether participants perceive that change occurs as a result of the participatory research process.

Evaluating the Participatory Research Case in the Piriápolis Artisanal Fishery

Process Criteria

Problem or Topic to be Addressed of Key Interest to Local and Additional Stakeholders

The lead author was the external agent initiating the participatory research process in Piriápolis, facilitating the stage of selecting the local problems to be addressed. After most fishers stated during informal interviews that the sea lion problem was the most urgent, additional stakeholders were invited, and all of them together defined the specific research question to answer. While doing this, participants made clear that the study had to contribute to solving the problem. Addressing a second local problem arose on the way. Concomitant with the progress of the planning stage of the study on sea lions’ impact, the group started to discuss another concern brought up by fishers: the market competition of imported Pangasianodon (farmed catfish from Vietnam, locally known as pangasius), which is sold at a cheaper price than local fish. Once participants discussed this problem and possible actions, the group agreed to work on communication strategies to promote local fish and the local fishery. As part of that effort, the First Artisanal Fisheries Festival in Piriápolis was organized. All participants’ interest in the two topics was confirmed throughout the process during individual interviews.

Participation of Interested Stakeholder Groups in the Selected Problem or Topic (Stakeholder Diversity)

Primary stakeholders who were invited to the experience in Piriápolis consisted of the management agency in charge of fisheries and marine mammals (DINARA), the National University (UDELAR) biologists/ecologists doing research about sea lions and the interaction with the fishery, and biodiversity conservation-oriented NGOs. DINARA’s Artisanal Fisheries Unit, four University scientists, and one NGO (SOS—dedicated to marine animal rescue and rehabilitation) accepted the invitation, valuing the opportunity of being part of a multi-stakeholder participatory research initiative together with fishers. Nevertheless, DINARA’s Marine Mammals Department and two NGOs could not participate. Of special interest is the former’s response, whose manager stated that solving conflicts was not part of his duties. Secondary stakeholders who were invited included additional governmental organizations (Coast Guard and Port Authority), middlemen, and a sustainable development-oriented NGO (Ecópolis—a multisectoral, umbrella group of Piriápolis citizens and local organizations that promote sustainable development). All except the latter could not participate. One social scientist in communication and culture studies joined the group since the second workshop. During the final interviews, 10 out of 15 participants identified additional stakeholders, governmental and non-governmental, that should have participated (e.g., DINARA’s Marine Mammals Department, Coast Guard, and Port Authority). Nevertheless, stakeholder diversity was valued during workshop evaluations recurrently. Participants stated that the diversity of stakeholders motivated their participation.

Participants’ Representativeness

Even though a continuous effort was made throughout the process to invite all kinds of local stakeholders, only ten fishers participated in workshops. In fact, fishers’ low participation was repeatedly identified by the four stakeholder groups as a negative aspect (for reasons about low participation see Zurba and Trimble, under review). Nevertheless, in several opportunities fishers expressed that they represented the rest, and after each workshop they shared with non-participating fishers the progress which was being done. Moreover, fishers who did not attend workshops participated in other ways throughout the process, from deciding which topic should be addressed, through contributing with their knowledge about sea lions’ impact, to giving ideas and support for the organization of the Festival. Not only fishers’ representativeness was questionable but also DINARA’s. Throughout the process, the participating manager would sometimes identify himself as the DINARA representative, whereas at other times he would state that he was participating just because he was interested in the project. This created confusion among participants, mainly fishers and scientists, who expected to see a DINARA manager at the participatory research table. It is worth mentioning, however, that when DINARA was formally invited to the participatory research initiative (early 2011), the General Director decided that the Artisanal Fisheries Unit would become involved.

Involvement of Participating Stakeholder Groups in Every Research Stage

This criterion structured the participatory research process in Piriápolis. The multi-stakeholder group collectively defined a research question: due to the high impact of sea lions on long-lines (a costly gear) and the lack of scientific data about that in Piriápolis since 2002, participants decided to investigate the current interaction between sea lions and long-lines. The study methods were also defined by the group; a protocol to fill out collaboratively during fishing trips was co-produced. When participants were asked to comment on the collective generation of the protocol, opinions differed among stakeholders, although they were always positive. Fishers stated that the full participation of all members was a must because that is how groups work, also adding that data would be more precise and unbiased. Scientists appreciated that fishers suggested collecting new data and stated that by participating in the methodology stage, fishers would later believe in the study findings. Lastly, DINARA and NGO representatives highlighted the complementarity of everyone’s viewpoints and contributions. Another example to illustrate the involvement of all stakeholder groups in every stage was the organization, development, evaluation (including its planning stage), and publicity of the Festival.

Facilitation

Participants’ opinions about the facilitator role were all positive, valuing several aspects: its impartial nature, of special relevance when the topic discussed is complex and controversial (such as sea lions); its task of making sure that everybody participates and nobody monopolizes conversations; and its task of keeping the discussions focused and the workshop activities on time. Moreover, participants associated the respectful dialogue and pleasant environment, a recurrent theme during workshop evaluations, with the facilitator’s role and the rules for a good dialogue which were explained at the beginning of each workshop.

Collective Decision Making Through Deliberation

While evaluating every workshop, participants identified positive aspects which relate to this criterion, such as opinions exchange (including differing viewpoints), openness to other points of view, and getting to common agreements. Interestingly, scientists and fishers noted that dialogue became nicer and reaching consensus easier when the second major problem (pangasius) started to be addressed, because it was less controversial than sea lions. During the final interviews, all participants stated that the opinion of every member of the group had been considered during the participatory research process.

Appropriate Information Management

Participants appreciated the information that others shared at workshops. For example, fishers found the presentations done by scientists about sea lions interesting, whereas scientists appreciated getting to know characteristics of the local fishery through fishers. There were times when scientists would exchange comments among themselves, for example questioning their study methods. In spite of the facilitators’ effort in asking participants to explain the jargon they used, some fishers stated that they could not understand a few terms. On several occasions during workshops, fishers also had to explain their jargon to the rest of participants. Differences in the communication means used by participants (some cell phone and some internet) were identified as a weakness of the participatory research process.

Adaptability Through Iterative Cycles of Planning, Acting, Observing, and Reflecting

Adaptability was evident in the participatory research process in Piriápolis. Already in the second workshop, stakeholders who had been reunited to address the sea lion problem in the fishery started to address a second problem (pangasius), initially seen as unrelated to the former. Perceptions about this transition varied among stakeholder groups. Fishers considered that the second problem was more important than the first one, although they added that the group should not leave the sea lion problem unattended. Scientists appreciated the transition toward pangasius and the Festival for two main reasons: (i) it would unite the group and (ii) if fishers got to sell more fish to consumers and/or at a better price, they would perceive the sea lion problem as less marked. The DINARA manager, on his part, was not much concerned about the topics being addressed but about the process itself, which would build trust among participants. Finally, addressing the second problem was perceived by NGO representatives as an opportunity to contribute to improving fishers’ quality of life, with the ultimate goal, according to one of them, of decreasing the conflict with sea lions.

Cost-effectiveness of the Process

All participants invested time to participate (e.g., they sacrificed time with their families and time for their jobs). Scientists and the manager would come from Montevideo to Piriápolis for workshops (3-hour round trip). Sometimes fishers would come to workshops tired after fishing trips, sacrificing sleeping time, and occasionally they would sacrifice a fishing trip. In addition to the manager’s participation, DINARA provided financial support to the Festival by printing 5,000 brochures. Except for one biologist and one fisher who participated in the first workshop and then gave up because of lack of time, the rest kept participating, becoming part of POPA. During the final interviews, when participants were asked what had motivated them to continue participating, several reasons came up: the formation of POPA; the commitment and motivation of group members; the diversity of stakeholders; and the respectful dialogue among them. Nevertheless, it was noticeable that some participants invested and sacrificed more than others for the group, and individuals’ dedication fluctuated over time (as expected). Table 2 summarizes the findings from applying the process evaluation criteria to our case study.

Outcome criteria

Achievement of Objectives

During the final interviews several participants noticed that stakeholders’ interests changed from being individual to being collective. Some participants were surprised with this change because they thought it would not be possible to integrate everybody’s interest, whereas others were expecting this shared group vision to arise. All participants stated that their personal objectives had been integrated into the group objectives. Nevertheless, one of the group objectives, to study the sea lions’ impact on long-lines, was not accomplished, and thus the quality of the research could not be evaluated. The data collection phase did not start due to aspects related to the seasonality of the fishery (fishers migrate along the coast following fish resources) and low fisher motivation, among others. Conversely, the objective of promoting artisanal fisheries through the Festival was noticeably achieved. Nonetheless, two fishers stated that the pangasius problem should have been addressed more explicitly. It is noteworthy that the research activities related to the initial problem (sea lions’ impact) were resumed in 2013 with a government-funded research proposal by POPA (see “Influence and impacts of the results” section).

Outcomes and Process Perceived as Successful

Participants identified elements of success related to the outcomes and to the process itself. The four stakeholder groups referred to the Festival as a main accomplishment of POPA: many people attended; artisanal fisheries were called to the attention of the public and different organizations; and it enhanced fishers’ unity and increased fishers’ self-esteem. Moreover, this accomplishment was perceived to have strengthened the group, which became better prepared to investigate the initial topic (sea lions). However, not studying sea lions’ impact made the participatory research initiative not fully successfully, participants explained. As additional successful elements, participants highlighted the honest and respectful dialogue, as well as the group continuity throughout several months. Similarly, group cohesion, trust, respect, honesty, and tolerance, along with a closer relationship between fishers and other stakeholders were the main strengths of the process, according to participants. The main weaknesses, as they stated, were the low number of participating fishers, the difficulty of all participants attending workshops, and the obstacles when dividing tasks.

Co-production of Knowledge

All participants recognized that co-production of knowledge took place. They gave examples of new approaches or strategies generated by the group, such as (i) the process of collective production of the data collection protocol in the sea lion study; (ii) approaching the sea lion problem considering its connection to additional fishery problems, such as pangasius imports and the relationship between fishers and middlemen; (iii) the First Artisanal Fisheries Festival as a strategy to promote artisanal fish consumption and fishers’ valorization; and most importantly, (iv) participatory research as an approach to address a problem, working in a group with a common goal, respecting other stakeholders’ opinions, and learning from each other. Furthermore, all participants except one fisher (who explained that both forms of knowledge did not integrate when discussing sea lion issues) stated that there were situations in which local and scientific knowledge were integrated. Examples of these situations included the collective production of the data collection protocol, brochures, and captions for the photo exhibition during the Festival.

Learning

All participants stated that they learned throughout the participatory research process. For example, fishers explained that they learned to listen to others who might think differently, to relate with other people, and information about sea lions. Scientists stated that they learned about the participatory research approach, the importance of fishers’ and other stakeholders’ inclusion, and to listen to others. The manager pointed out that he learned to participate, because participating requires learning and practicing. NGO representatives learned how to carry out a discussion or debate in an organized way, by means of a facilitator, and to prioritize the group interest over the individual, among others.

Strengthened Social Networks

New relationships were built between participants from the four stakeholder groups: fishers-DINARA, fishers-scientists, fishers-NGOs, DINARA-scientists, DINARA-NGOs, scientists-NGOs. New relationships between participants from the same group were also formed (fishers-fishers, scientists-scientists). Moreover, the majority of existing relationships improved and trust among participants increased over time (Trimble and Berkes 2013). The multi-stakeholder group that was formed (POPA) can be perceived as the result of the consolidation of participants’ relationships, working together for common goals.

Conflict Resolution

Three main conflicts which were present at the beginning of the participatory research initiative were allayed to some degree during the process. First, the conflict between fishers and DINARA had a turning point during the Festival and its organization process, when fishers noticed that the manager was very committed to this group activity. Second, the conflict between fishers and scientists was allayed when the group started to work on the second problem (pangasius), not as controversial as sea lions. Finally, the conflict between fishers and the conservation-oriented NGO was minimized or at least managed. For example, fishers who had initially stated that they could not exchange a word with the NGO representative because of their opposing interests got to work with him and be part of the same group. Nevertheless, most participants recognized that the change in their relationships with people in the group had not influenced their opinion about the organization they belong to, arguing that they cannot judge the organization based on a person.

Legitimacy

The participatory research process seems to have been validated by participants. While evaluating their first participatory research experience, they considered appropriate to promote this approach to address environmental problems, due to three main arguments: (i) multiple understandings, perspectives, and judgments are needed; (ii) participation makes people more involved in the problem and the research process, fostering rules compliance; and (iii) lay people should have the opportunity to look for solutions to their problems with academics. The study that the group intended to carry out about sea lions’ impact did not get to the data collection phase, and thus it is unknown whether its findings would be legitimate to all. However, the participating biologists highlighted that by doing participatory research fishers would accept the results. Regarding the second action taken by the group, there are indications that the Festival was seen as valid, not only by the group but also by non-participating fishers, who offered help to the organization and/or made positive comments about the event. Studying in detail external legitimacy of the process and its outcomes (in the Piriápolis fishing community, DINARA, other government agencies, University, and NGOs) is a gap for future research. Nonetheless, the ability of the group to receive funding from non-governmental organizations (Global Greengrants Fund, Yaqu-pacha) and from the government (see “Influence and impacts of the results”section) should be considered as a measure of external legitimacy.

Influence and Impacts of the Results

Although it was very soon to evaluate the influence and impacts of the participatory research initiative (less than one year from the beginning), participants stated that some impacts were already achieved through the Festival because this was a successful event in which the society, Municipal Government, DINARA, and other fishers participated. Participants expected the participatory research project to impact on DINARA (e.g., increased interest in artisanal fishers; and fisher participation in addressing problems and making decisions), fishers (e.g., increased and continuous participation in the participatory research), scientists (e.g., initiating participatory research), and the broader society (e.g., consuming more local fish). In late 2012, less than two years after the beginning of the participatory research initiative, following the offer of the group biologists and the suggestions made by the fishers, POPA designed a research project to try fish traps as alternative gear that could mitigate sea lions’ impact, applying for government funding (DINARA—ANII-National Agency for Research and Innovation). POPA biologists could have decided to apply for this funding with a conventional research proposal but they did not, suggesting somehow that they advocate the participatory research approach. POPA fishers traveled from Piriápolis to DINARA’s main office in Montevideo for group meetings in which the research proposal was defined, a sign of their commitment. Furthermore, another division of DINARA was involved in the proposal (the Fisheries Technology Lab), opening up a possibility for increased DINARA’s representativeness and external legitimacy of participatory research. The research proposal which was jointly developed by participants as co-researchers was approved in mid 2013. Table 3 summarizes the findings from applying the outcomes evaluation criteria to our case study.

Discussion and Conclusion

From its origin in the social sciences (Fals Borda 1987), participatory research has been increasingly used in interdisciplinary fields such as community development and environmental management (Wilmsen et al. 2008; Chevalier and Buckles 2013). This has accompanied the trend of involving stakeholders in the processes of addressing conflicts that affect them, and also in making policy decisions (Walker and Daniels 2001), following normative, substantive, and instrumental arguments (Fiorino 1990). Our research offered a small contribution in this direction by addressing three main gaps found in the participatory research literature (Blackstock et al. 2007; Shirk et al. 2012).

First, we proposed seventeen criteria under two categories (process and outcomes) to evaluate participatory research initiatives. By applying them to a case study in coastal Uruguay, we provided an example of how the assessment of the criteria can be operationalized. Second, the analysis of a case study which illustrates a collegial or empowering participatory research project (Biggs 1989, Kindon 2008) intended to answer the call to improve the nature of participatory research initiatives in natural resources management, where power sharing has been difficult to achieve (Wiber et al. 2004; Arnold and Fernandez-Gimenez 2007). In this regard, the process evaluation criteria, such as the problem to be addressed which must be of key interest to local and additional stakeholders; involvement of interested stakeholder groups in every research stage; collective decision making through deliberation; and adaptability through iterative cycles of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting, should be considered as the conditions or guidelines to develop empowering participatory research. Third, our case study is significant because it provided evidence of the positive outcomes of participatory research, which include co-production of knowledge, learning, strengthened social networks, and conflict resolution. This emphasizes that participatory research is an approach that can help stakeholders (e.g., communities, academics, and government) to deal with the uncertainties of complex social–ecological systems (Berkes et al. 2003).

Even though evaluation criteria were classified under process or outcomes, the two categories are closely interrelated, and thus ineffective processes (e.g., fishers as collaborators of scientists rather than as co-researchers, or unbalanced power sharing during decision making) might lead to undesirable outcomes, such as increased distrust or conflicts (Fisher 2000; Blackstock et al. 2007). Furthermore, although this evaluation framework with process and outcome criteria is practical (i.e., it aids the evaluation of participatory research projects), it should be noted that the majority of the criteria refer directly or indirectly to the process (despite they being in the outcomes category), and thus they could be assessed throughout the process in a formative evaluation. This is explained by the foundational nature of participatory research: its process is what matters the most. As claimed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2005), the success of participatory research often depends on the progress of the process to enable empowerment, rather than on the information gathered as a result of the research. This does not mean, however, that the quality of the research is not important in a participatory research project, which is included as part of the Criterion Achievement of objectives.

Our case study in the artisanal fishery in coastal Uruguay provided some lessons for POPA and potentially for further initiatives elsewhere. Seventeen evaluation criteria were assessed but not all of them were achieved: some invited stakeholders decided not to participate (e.g., DINARA’s Marine Mammals Department); fishers’ and DINARA’s representativeness was questioned; academics’ and fishers’ jargon hampered information exchange among participants; the objective regarding the sea lion study was not accomplished (although it was later resumed); and existing conflicts among stakeholder groups (e.g., between fishers and DINARA) were not totally allayed. Instead of aiming to achieve all the criteria to the maximum degree in a first attempt, efforts should be directed to learn from the experience and adapt accordingly as the process continues. In this regard, in late 2013 POPA members (academics and fishers) started to interview non-participating fishers in Piriápolis, both to understand better the reasons for their non-involvement and to offer them different options to participate in the new project (assessment of fish traps to mitigate sea lions’ impact).

The continuation and replication of the participatory research approach could be promoted if participants did the job of sharing with their organization or fellows the experience in Piriápolis. The benefits or advantages that participants and stakeholder groups in general perceive from participatory research will also affect a wider use of this approach. First, scientists probably need to find scientific rigor within participatory research (including opportunities for publications) so that they do not underestimate this approach. A frequent challenge is that participatory research interventions are mistaken for local activism and/or “science for the people” which are based on outreaching the benefits and understanding of science to communities. Academics should neither see participatory research as less reliable or valid than more conventional approaches (i.e., traditional expert research, Cambell and Salagrama 2001) but rather as a tool or approach that holds the potential to improve the diagnosing, understanding, and management of complex environmental problems in a post-normal context of “science with the people” (Funtowicz and Ravetz 2000). Participatory research is particularly useful to address complex environmental problems on a local scale, but does not intend to replace conventional research. Integrating the participatory research approach into the University curricula will provide students with real-world experience (Chopyak and Levesque 2002) and will likely contribute to increasing their openness to other modes of doing science (e.g., respecting local knowledge instead of underestimating it because of its non-scientific nature). Second, motivating fishers to become co-researchers, looking for solutions to local problems in order to improve their reality, has proved not to be easy. Participatory research not only needs to persuade scientists about the validity of considering multiple forms of knowledge and understanding when doing research, but also fishers who might be hesitant or not confident about their contributions for every research stage (Cornwall and Jewkes 1995). Third, even though participatory research originally tended to involve primary stakeholders and researchers, we now know that engagement with stakeholders at all levels is essential, especially if policy makers are to be influenced by participatory research (Neiland et al. 2005; Trimble and Berkes 2013). Government agencies could adopt this approach considering that environmental conflicts are better managed through participatory processes.

To conclude, this research has identified criteria which may act as guidelines for the development of future empowering participatory research. The assessment of these criteria in participatory research projects will help improve the projects being evaluated as well as others, fostering learning from experience. It is imperative that an evaluation component is included in participatory processes such as participatory research. Efforts should be made in order to overcome the challenges identified during evaluation if participatory research is to be used more widely. For this to happen, government agencies, research/academic institutions, and communities should recognize that participatory approaches to research contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of environmental problems and analysis of solutions or actions to be taken, leading to improved environmental management.

Notes

Since late 2013, POPA members have been conducting a formative evaluation of their new project about the assessment of fish traps as alternative fishing gear that could mitigate the sea lions’ impact in Piriápolis.

References

Armitage D, Berkes F, Doubleday N (2007) Adaptive co-management: collaboration, learning and multi-level governance. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, British Columbia

Armitage D, Berkes F, Dale A, Kocho-Schellenberg E, Patton E (2011) Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Glob Environ Change 21:995–1004

Arnold JS, Fernandez-Gimenez M (2007) Building social capital through participatory research: an analysis of collaboration on Tohono O’odham tribal rangelands in Arizona. Soc Nat Resour 20:481–495

Bellamy JA, Walker DH, McDonald GT, Syme GJ (2001) A systems approach to the evaluation of natural resource management initiatives. J Environ Manage 63:407–423

Berkes F (2009) Social aspects of fisheries management. In: Cochrane KL, Garcia SM (eds) A fishery manager’s guidebook, 2nd edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, pp 52–74

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C (2003) Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bernard HR (2006) Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches, 4th edn. Altamira Press, Lanham

Biggs S (1989) Resource-poor farmer participation in research: a synthesis of experiences from nine national agricultural research systems. OFCOR Comparative Study Paper 3, International Service for National Agricultural Research, The Hague

Blackstock KL, Kelly GJ, Horsey BL (2007) Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecol Econ 60(4):726–742

Bocking S (2004) Nature’s experts: science, politics, and the environment. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Cambell J, Salagrama V (2001) New approaches to participation in fisheries research. FAO Fisheries Circular No. 965, Rome

Chevalier JM, Buckles DJ (2013) Participatory action research: theory and methods for engaged inquiry. Routledge, London and New York

Chopyak J, Levesque PN (2002) Community-based research and changes in the research landscape. Bull Sci Technol Soc 22(3):203–209

Conley A, Moote MA (2003) Evaluating collaborative natural resource management. Soc Nat Resour 16:371–386

Cornwall A, Jewkes R (1995) What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med 41(12):1667–1676

Dunn K (2008) Interviewing. In: Hay I (ed) Qualitative research methods in human geography. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, pp 79–105

Fals Borda O (1987) The application of participatory action-research in Latin America. Int Sociol 2(4):329–347

Fiorino DJ (1990) Citizen participation and environmental risk: a survey of institutional mechanisms. Sci Technol Human Values 15(2):226–243

Fisher F (2000) Citizens, experts, and the environment: the politics of local knowledge. Duke University Press, London

Funtowicz SO, Ravetz JR (2000) La ciencia posnormal: ciencia con la gente. Icaria, Barcelona

Gaventa J, Cornwall A (2001) Power and knowledge. In: Reason P, Bradbury H (eds) The sage handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. Sage Publications, London, pp 70–80

Guba EG, Lincoln YS (1989) Fourth generation evaluation. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Hartley TW, Robertson RA (2006) Stakeholder engagement, cooperative fisheries research and democratic science: the case of the Northeast Consortium. Human Ecol Rev 13(2):161–171

Kemmis S, McTaggart R (2005) Participatory action research: communicative action and the public sphere. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) The sage handbook of qualitative research sage publications. Thousand Oaks, California, pp 559–603

Kindon S (2008) Participatory action research. In: Hay I (ed) Qualitative research methods in human geography. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, pp 207–220

Krefting L (1991) Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Theory 45(3):214–222

Lázaro M, Trimble M, Umpiérrez A, Vasquez A, Pereira G (2013) Juicios Ciudadanos en Uruguay: dos experiencias de participación pública deliberativa en ciencia y tecnología. Montevideo

Ludwig D (2001) The era of management is over. Ecosystems 4:758–764

Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J (2002) Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 1(2):13–22

Neiland AE, Bennett E, Townsley P (2005) Participatory research approaches—what have we learned? The experience of the DFID Renewable Natural Resources Research Strategy (RNRRS) Programme 1995–2005. Summary document. Department for International Development, UK

Plummer R, Armitage D (2007) A resilience-based framework for evaluating adaptive co-management: linking ecology, economics and society in a complex world. Ecol Econ 61(1):62–74

Reason P (1994) Three approaches to participatory inquiry. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 324–339

Rowe G, Frewer LJ (2000) Public participation methods: a framework for evaluation. Sci Technol Human Values 25(1):3–29

Rowe G, Marsh R, Frewer LJ (2004) Evaluation of a deliberative conference in science. Technol Human Values 29:88–121

Shirk JL, Ballard HL, Wilderman CC, Phillips T, Wiggins A, Jordan R, McCallie E, Minarchek M, Lewenstein BV, Krasny ME, Bonney R (2012) Public participation in scientific research: a framework for deliberate design. Ecol Soc 17(2):29

Stephens JB, Berner M (2011) Learning from your neighbor: The value of public participation evaluation for public policy dispute resolution. Journal of Public Deliberation 7(1):Art No 10

Trimble M (2013) Towards adaptive co-management of artisanal fisheries in coastal Uruguay: analysis of barriers and opportunities, with comparisons to Paraty (Brazil). Dissertation, University of Manitoba

Trimble M, Berkes F (2013) Participatory research towards co-management: lessons from artisanal fisheries in coastal Uruguay. J Environ Manage 128:768–778

Trimble M, Johnson D (2013) Artisanal fishing as an undesirable way of life? The implications for governance of fishers’ wellbeing aspirations in coastal Uruguay and southeastern Brazil. Marine Policy 37:37–44

Trimble M, Araujo LG, Seixas CS (2014) One party does not tango! Fishers’ non-participation as a barrier to co-management in Paraty, Brazil. Ocean and Coastal Management 92:9–18

Walker GB, Daniels SE (2001) Natural resource policy and the paradox of public involvement: bringing scientists and citizens together. In: Gray GJ, Enzer MJ, Kusel J (eds) Understanding community-based ecosystem management. The Haworth Press Inc, New York, pp 253–269

Webler T, Tuler S (2002) Unlocking the puzzle of public participation. Bull Sci Technol Soc 22(3):179–189

Wiber M, Berkes F, Charles A, Kearney J (2004) Participatory research supporting community-based fishery management. Marine Policy 28(6):459–468

Wilmsen C, Elmendorf W, Fisher L, Ross J, Sararthy B, Wells G (2008) Partnerships for empowerment: participatory research for community-based natural resource management. Earthscan, London

Yin RK (1994) Case study research. Design and methods. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks

Zurba M, Trimble M (under review) Youth as the Inheritors of Collaboration: crisis and factors that influence participation of the next generation in natural resource management. Environmental Science & Policy

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the first author’s PhD research supported by the University of Manitoba Graduate Fellowship, Manitoba Graduate Scholarship, and the International Development Research Centre through the IDRC/CRC International Research Chairs Initiative. Special thanks to the members of POPA (Por la Pesca Artesanal en Piriápolis) for their unconditional support. Patricia Iribarne provided invaluable assistance in the field. The intellectual support of Fikret Berkes (Canada Research Chair in Community-Based Resource Management) is deeply acknowledged. We also thank Jennifer Arnold, two anonymous reviewers, and the Editorial Board for their important contributions to this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trimble, M., Lázaro, M. Evaluation Criteria for Participatory Research: Insights from Coastal Uruguay. Environmental Management 54, 122–137 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0276-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0276-0