Abstract

Numerous studies have indicated a broad-based support for open space preservation and protection. Research also has characterized the public values and rationale that underlie the widespread support for open space. In recognition of the widespread public support for open space, various levels of government have implemented programs to provide public access to open space. There are many different types of open space, ranging from golf courses, ball parks, wildlife areas, and prairies, to name a few. This paper addresses questions related to the types of open space that should be prioritized by planners and natural resource managers. The results of this study are based on a stratified random sample of 5000 households in Illinois that were sent a questionnaire related to their support for various types of open space. Through a comparatively simple action grid analysis, the open space types that should be prioritized for public access include forest areas, stream corridors, wildlife habitat, and lakes/ponds. These were the open space types rated of the highest importance, yet were also the open space types rated the lowest in respondent satisfaction. This kind of analysis does not require the technical expertise of other options for land-use prioritizations (e.g., conjoint analysis, contingent valuation), yet provides important policy directives for planners. Although open space funds often allow for purchase of developed sites such as golf courses, ball parks, and community parks, this study indicates that undeveloped (or nature-based) open space lands are most needed in Illinois.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Throughout the United States, there is broad support for open space preservation and protection as evidenced by research at national, state, and local levels. A survey by the National Governor’s Association showed that 46 of the 50 states have some type of open space preservation program (National Governor’s Association as cited in Geoghegan 2002). In 2002, $2.3 billion were approved by voters in 94 communities in 23 states for the acquisition and restoration of open space lands (Trust for Public Land 2002). Polls and research at state and local levels have found significant support for open space acquisition. A poll of likely voters in Virginia concluded that protecting air and water quality as well as open space should be a higher legislative priority than cutting taxes. The same poll also concluded that Virginia voters believed that preserving open space was as important as improving schools and roads (Trust for Public Land 2002). A survey of citizens of Duluth, Minnesota indicated there was overwhelming support for a system of land corridors linking many open space areas (Kreag 2002). In short, support for open space preservation and restoration has been found throughout the American public.

Not only is support for public open space widespread, but also one could argue it is well-reasoned public judgment. Three decades ago, Berry (1976) identified several widespread and distinct rationales used by people to protect open space in their community and drew on the following values to characterize the rationales: ecological function, protection of public health, contemplative and aesthetic values, provision of recreational opportunities, community and economic development, and appreciation of native wildlife and plants. Following Berry’s work, several other studies also have indicated a depth to the public arguments to protect open space. For example, McCurdy and McClure (2002) indicated that the increasing rate of urbanization needs to be addressed through proper planning of open space, and identify a strategy referred to as “greenprinting” to ensure a high “quality of life, clean air and water, recreation, and economic health” (p. 27; see also Trust for Public Land 2002). Similarly, Kreag’s (2002; see also deHaven-Smith 1988) research depicted several reasons for which citizens of Duluth, Minnesota support open space protection, including growth management, community identity and heritage, scenic beauty and visual quality of landscape, protection of ecosystem dynamics, provision of recreational opportunities, and improvement in quality of life for residents. From the point of view of economists, all of these are public goods that are not necessarily accounted for in the price of land and therefore lead to a misallocation of undeveloped land. Referred to as market-failure, this misallocation would justify the provision of undeveloped land by government (Wolfram 1981). Not all supporters of open space protection subscribe to all of these reasons. The numerous reasons identified suggest extensive arguments that lead citizens and experts to support open space protection.

Whereas billions of dollars have been allocated to acquire, preserve, and restore public open space lands throughout the United States, there has been little discussion about how these dollars should be spent. Most policy research has focused on the economic value of open space protection to define public preferences (see Fausold and Lilieholm 1999 for a review). These studies tended to approach open space from the perspective of impact on property values (Crompton 2001) or respondent’s willingness to pay for open space acquisition and protection (Croke and others 1986, Loomis and others 1999). Some researchers have attempted to include some noneconomic measures of public preference for farmland, environmental protection, and visual quality within the development of their economic models (Kline and Wichlens 1998, Duke and Aull-Hyde 2002). Such studies have provided insight into predicting individual choices and accounting for tradeoffs within the context of land-use change. However, questions still remain regarding the kinds of open space most needed.

Decisions regarding open space acquisition are often left to planners and other experts who may not be aware of the benefits of various types of open space, may not fully understand the kinds of open space preferred by the public, or may develop land-use objectives inconsistent with the values of a community’s citizens. For example, Airola and Wilson (1982) suggested that planners may not recognize the value of undeveloped open space in urban communities that are not formal parks yet provide opportunity for contact with less-altered environments. In a study of citizens and experts in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Tannery (1987) found that experts and citizens differed in their preferences for Albuquerque’s open space. For example, 86% of experts, compared to 35% of citizens, felt that a citywide trail system (linking open space areas) was needed (Tannery 1987, p. 372). Finally, planners may seek to maximize functions such as ecological diversity, total acreage preserved, preserving the largest continuous blocks available, and preserving lands that are most threatened by development (Lynch and Musser 2001, Thomas 2003). Although these functions are important, the preferences of community members can be lost in an effort to fulfill these functions. For any program of open space acquisition to be effective, potential gaps in knowledge between planners and citizens need to be addressed and balanced with a need to fulfill the different functions of open space.

Across most segments of the American public, there is support for open space protection and restoration. For open space acquisition programs to be successful, decision-makers need to prioritize the types of public open space desired by citizens. Rather than asking does the public value open space protection, the research questions of this study are related to identifying the kinds of open space desired by the public, and being sensitive to variability in preferences across a range of open space types. At least two premises of the study are that decision-makers need to be aware of both diversity in open space types and the relative public preferences of each type of open space.

Open Space in Illinois

Illinois has approximately one million acres of public open space lands. Although Illinois has a diversity of public open space, it ranks 48th in the United States in public open space per capita (McDonald and others 2003). The lack of public open space in Illinois may largely be attributed to the value of much of the land for agriculture. Sixty percent of the land cover (8,751,900 ha) is in croplands comprising mostly corn and soybeans. The second largest land cover is grasslands that comprises 19% (6,932,409 ha) of Illinois. Examples of the predominant grasslands would be private lawns, pasture, and transportation and utility right-of-ways. Although there is a growing prairie restoration movement in Illinois, prairie still comprises less than 0.1% of the state. About 5% of the land is classified as urban or built-up, leaving 15% in wetland, open water, or forest. The problem for land-use planners in Illinois is to carve more publicly accessible open space from the current mixture of land cover.

Purpose

To address the need for publicly accessible open space in Illinois, the State Legislature passed the Open Lands Trust Act (OLT) in 1999. The purpose of the OLT was to provide grants to be disbursed by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) to local governments to acquire lands for watershed protection, parks, wildlife, and natural resource–related recreation. The purpose of this study was to assess Illinois citizens’ preferences for open space acquisition, and to do so in a way that would be comparatively simple for planners to undertake themselves. To achieve this purpose, we assessed support for public open space acquisition throughout Illinois. Citizens’ evaluations of 16 types of public open space were examined in an effort to prioritize acquisition of each of the 16 types.

Procedures

The Meaning of “Open Space”

Because of the predominance of agricultural lands in central Illinois and the possibility that citizens might have differing views of such land as open space, clarifying the meaning of open space was an important first step. Many studies have classified farmland as open space due to concerns to protect rural heritage within a rapidly urbanizing context (e.g., Duke and Aull-Hyde 2002, Kline and Wichlens 1998, Trust for Public Lands 2001), Whereas in Illinois, agricultural lands still dominate the land cover of the state, and thus may not be considered either threatened or framed as “open space.” Because of potential confusion with the meaning of “open space,” a preliminary telephone study was conducted to assess the public meanings of open space from a small sample (N = 50) of Illinois citizens. There was variability within this sample regarding the referent of the term “open space.” Many respondents did not consider farmland to be open space, whereas others referred to farmland as “open space.” Because of the potential confusion, we excluded farmland as a type of open space, in part because such land is not publicly accessible. We explicitly defined “open space” within all correspondence to respondents as being “natural areas, parks and recreation areas, wildlife habitat, and lakes and streams; agricultural lands are not defined as open space.”

Data Collection

Data were collected through a general population survey between February and April 2002 following a modified Dillman (2001) procedure. The questionnaire was designed to elicit respondent characteristics, their use of open space, attitudes about community issues, and importance of and satisfaction with various types of open space. Five thousand randomly selected households stratified by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources administrative region were mailed an eight-page questionnaire. One thousand eight hundred fifty were returned for an adjusted response rate of 38%.

Respondents were asked to consider a variety of open space types including both undeveloped and developed open spaces. Undeveloped open space included areas such as forest areas, wetlands, prairies, and lake/ponds. Developed open space included areas such as bike paths, playgrounds, playing fields, and community parks. The importance of, and satisfaction with, 16 types of open space were assessed with five-point unipolar scales ranging from “Not at all Important/satisfied,” to “Extremely Important/satisfied.” Items were worded, “How important to you are each of the following types of open space?” and “How satisfied are you with the amount of open space currently available in your community?”

Analysis

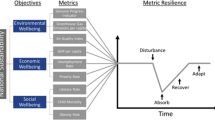

Action Grid Analysis (AGA) was used to identify and prioritize the types of open space that could be acquired. AGA (Blake and others 1978) is a modified version of Martilla and James’ (1977) importance-performance analysis and results in an orthogonal grid that portrays priorities for management. AGA analyses are popular techniques to allow resource managers to gain valuable feedback from visitors and other clients to improve service quality (Oh 2002, Huan and others 2002) and prioritize agency efforts for natural resources managers, including visitors’ perceptions of park impacts (Hammitt and others 1996), visitor evaluation of information center services (Mengak 1985), and evaluation of user preferences for various natural resource recreation facilities (Hollenhorst and others 1992).

One strength of AGA is the ease of interpreting the results. The action grid is actually a set of x and y-axes corresponding to “importance” and “satisfaction,” respectively. The four quadrants of the graph are divided into priorities for management. Quadrant I includes open space types that are rated high in both importance and satisfaction, and referred to as “well provided.” Open space types in this quadrant are important to respondents but because they are rated high in satisfaction, acquiring new open space of this type is not a priority because current provision of these open space types meets the respondents’ desires for them. Quadrant II includes open spaces that are rated high in importance but low in satisfaction, and are referred to as “high priority.” Open spaces in this quadrant are high priority for acquisition because respondents’ find current provision levels inadequate. Quadrant III includes open spaces that are rated low in both importance and satisfaction and are referred to as “low priority.” These open space types are unimportant to the respondents and while the satisfaction ratings are low, scarce resources can be better utilized elsewhere. Finally, Quadrant IV includes open spaces rated low in importance and high in satisfaction, referred to as “meeting/exceeding the need.” Current provision of these open spaces is more than adequately provided, so priority for acquiring more of these should be low.

AGA has a significant practical problem, that is, the question as to where to plot the grid’s crosshairs. The two approaches to this problem plot the origin either at the center point of the scales or the observed means (Oh 2001). For this study, mean ratings of importance and satisfaction for each open space type were converted to z-scores based on the grand mean of their respective open space types. In this way, plots across the regions are on the same scale and retained their unique positions relative to one another.

Results

Respondent Characteristics

Of the respondents, 39% were female, most were more than 50 years old, 88% identified themselves as “Caucasian,” just over one third (37%) had completed at least a bachelor’s degree from a 4-year college or university, and two thirds (66%) reported a household income less than $60,000 per year. Most of the respondents (85%) were raised in communities with populations less than 100,000, a plurality (42%) currently reside in communities with populations between 10,000 and 100,000, and 59% have lived in their current community for more than 20 years. The average household size was 2.5 persons, with 34% reporting children living in the household.

Compared to the general population of Illinois residents, this sample is more male, older, white, more educated, and wealthier. The 2000 census indicates that Illinois residents were 51% female, 35 years as a median age, 74% Caucasian, 26% had completed at least a bachelor’s degree, and that the median income was $47,000 (U.S. Census Bureau 2000).

Respondents had participated in a broad array of outdoor recreation activities in the previous 12 months and many frequently visited open space areas. On average, respondents participated in seven activities, with walking, driving/sightseeing, gardening, and observing wildlife being the most popular activities (81%, 64%, 56%, and 53%, respectively). Only 6% claimed to have not visited an open space area, whereas 58% indicated visiting open space areas more the 10 times in the past year.

General Support for Open Space

As with other studies examining public attitude toward open space, support for its acquisition was widespread. More than 50% of the respondents who had an opinion about open space in Illinois agreed with statements supporting open space acquisition. Figure 1 illustrates the agreement level of respondents to various open space items.

Support for Open Space Types

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations for the “importance” and “satisfaction” ratings for each of the 16 open space types. “Lakes/ponds” had the highest mean importance rating, whereas “hunting areas” had the lowest. The open space type with the highest rated satisfaction was “public golf courses” and the lowest were “stream corridors” and “wetlands.”

Natural, undeveloped areas were generally found in the “high priority” quadrant (Figure 2). This category included places such as forest areas, stream corridors, wildlife habitat, and lakes/ponds. Developed recreation areas were often found in the “well provided” quadrant. These included state, community, and neighborhood parks. Open spaces for specialized activities such as public golf courses and playing fields were found in the “Meeting/exceeding the need” quadrant. Finally, prairies and wetlands were generally found in the “Low Priority” quadrant along with walking trails.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to provide Illinois policy makers with data based on citizens’ assessments to help them prioritize open space acquisition across Illinois using Open Lands Trust monies set aside by the state legislature. As a state, Illinois lags far behind other states in the Midwest region in the amount of open space acreage, particularly acreage per capita. A substantial majority of respondents indicate that protecting open space is an important statewide issue and that the state must continue efforts for protecting open space. Many did not think there was sufficient open space in their communities, and they favored setting aside money for acquiring public open space before it becomes lost to development.

Residents indicated that natural areas are important; however, they also indicated a low level of satisfaction with the amount of such areas in the state of Illinois. Although the acquisition of open space areas classified as natural areas should be a priority, all types of open space areas should be considered. A goal of an acquisition program should be to move natural areas from quadrant II “high priority” to quadrant I “well provided.” Although developed park areas are currently “well provided” and fall in quadrant I, efforts to acquire additional open space for park areas should be continued so that such open space areas continue to be “well provided” to meet future demand.

On the other hand, a much lower priority should be given to open space types in quadrants III and IV. The open space types in quadrant IV (e.g., hunting areas, golf courses, and sport fields) appear to be less important, although citizens are quite satisfied with the amount of these open space types. Citizens were less satisfied with the amount of prairies, bicycle paths, and wetlands represented in quadrant IV; however, these types are also less important to citizens than other open space types. Therefore, if based solely on the preferences of citizens, acquisition of such types should be a lower priority.

Open spaces rated low in importance and low in satisfaction, such as prairies and wetlands, may be considered a low priority for acquisition, but although the public does not find them important, they may still be important to consider for acquisition. When their ecological functions are considered along with the overall public priority that supports improvements in ecosystem health, prairies and wetlands may be more important to acquire than the public perceives. In this case, expert knowledge is important because it seems that the public may not fully understand ecosystem functions related to prairies and wetlands.

Furthermore, these findings suggest that developed open space needs cannot be ignored even though they are evaluated in the “Well Provided” quadrant. Although these open space types were generally rated higher in satisfaction than natural areas, they also received high importance ratings. These areas included neighborhood, community, and state parks. Additional acquisition of open space for development into formal parks may not be necessary, but their provision should be continued at a similar or the same level.

Finally, it is important to note that these results reflect broad patterns among respondents. The results displayed are based on overall averages. Lost in these results are the nuances of the ways that participation in different recreational activities might affect open space preferences as revealed in AGA. For example, overall importance and satisfaction scores for hunting areas were 2.57 and 3.23, respectively, putting hunting areas in the “meeting/exceeding the need” quadrant because it is rated low in importance and high in satisfaction. However, in this study, hunters made up 15% of respondents. If we examine the differences between hunters and nonhunters, we find that hunters report that hunting areas are significantly more important than they are for nonhunters (M = 4.08, M = 2.26 respectively, t = 26.91, P < 0.05), and they are significantly less satisfied with hunting areas than nonhunters are (M = 2.75, M = 3.38, respectively, t = –8.24, P < 0.05). For hunters, hunting areas would be in the “High Priority” quadrant instead of the “Meeting/exceeding the need” quadrant. This nuance is relevant to policy-making because small-sized groups with large stakes in a given land-use designation are not fully analyzed by an action grid of the general population.

Action Grid Analysis as a Tool

Action grids are a simple way for researchers to communicate the needs of citizens to planners, but they are not without shortcomings. AGA is helpful because it represents citizens’ evaluations in ways that are clear and understandable. Data collection is fairly simple and the results are rich. Combined with more complex economic and attitudinal analyses, AGA serves as a guide for the allocations of scarce resources.

Although AGA is highly advantageous, it is not without some shortfalls that should be addressed. As previously mentioned, there is the practical problem of where to plot the crosshairs. Different plotting methods will produce different interpretations. In this case, the data were statistically normal and the measurement scales were unipolar, so it was chosen to place the crosshairs at the overall mean. In other cases, it may be best to plot the crosshairs at the scales’ midpoint, especially if the scales are bipolar. Furthermore, interpreting the graphs is complicated by the crosshairs because the quadrants created do not indicate absolute categories. Items close together yet on different sides of the crosshairs may not necessarily be statistically different.

A second important issue related to the use AGA analysis in this context is that there may be some ambiguity to the meaning of “Importance” and “Satisfaction.” The importance questions asked “How important to you is each type of open space?” This leaves the meaning of importance open to some interpretation by the respondent. At issue is the question of “important to me for what?” The context effects of item ordering could play an important role in altering responses, biasing results toward topics early in the questionnaire. For example, if earlier questions asked about recreational activities, respondents may rate the importance of the open space types for recreation in the community, and largely ignore other values and benefits of open space. In the end, the analysis would only reveal those open space types that were important for recreation and not for the other values people may hold for open space.

Finally, it is important to consider the relationship between importance and satisfaction (Oh 2002). It is possible that the more important an open space type, the more satisfied the respondent may be. The degree and magnitude of the correlations could reduce the effectiveness of the AGA grids as a tool for policy making because, in the case of a positive correlation, most of the items would fall into the “well provided” and “low priority” quadrants and in the case of a strong negative correlation, most items would fall into the “high priority” and “meeting/exceeding the need” quadrants. The study presented here was free of this concern because there was no significant correlation between Importance and Satisfaction; however, future researchers should be aware of this possibility when considering the use of AGA.

Conclusion

Across the 16 types of open space, respondents reported the need for more natural areas, such as forested areas, stream corridors, wildlife habitat, lakes/ponds, natural areas, and walking trails. These were the open space types that were rated of the highest importance, yet were also the open space types rated lowest in satisfaction. The findings indicate that acquisition of open space should focus on acquisition of these specific types of open space to best meet the public need.

Literature Cited

N. M. Airola D. Wilson (1982) ArticleTitleRecreational benefits of residual open space: A case study of four communities in Northeastern New Jersey Environmental Management 6 471–484 Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF01868376

D. Berry (1976) ArticleTitlePreservation of open space and the concept of value The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 35 113–124

B. F. Blake L. F. Schrader W. James (1978) ArticleTitleNew tools for marketing research: The action grid Feedstuff 50 38–39

K. Croke R. Fabian G. Brenniman (1986) ArticleTitleEstimating the value of natural open space preservation in an urban area Journal of Environmental Management 23 317–324

J. Crompton (2001) ArticleTitleThe impact of parks on property values: A review of the empirical evidence Journal of Leisure Research 33 1–31

D. A. Dillman (2001) Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method John Wiley and Sons New York

L. deHaven-Smith (1988) ArticleTitleEnvironmental belief systems: Public opinion on land use regulation in Florida Environment and Behavior 20 176–199

J. M. Duke R. Aull-Hyde (2002) ArticleTitleIdentifying public preferences for land preservation using the analytic hierarchy process Ecological Economics 42 131–145 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00053-8

C. J. Fausold R. J. Lilieholm (1999) ArticleTitleThe economic value of open space: A review and synthesis Environmental Management 23 307–320 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s002679900188 Occurrence Handle9950694

J. Geoghegan (2002) ArticleTitleThe value of open spaces in residential land use Land Use Policy 19 91–98 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0264-8377(01)00040-0

W. E. Hammitt R. D. Bixler F. P. Noe (1996) ArticleTitleGoing beyond importance-performance analysis to analyze the observance of park impacts Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 14 45–62

S. Hollenhorst D. Olson R. Olson (1992) ArticleTitleUse of importance-performance analysis to evaluate state park cabins: The case of the West Virginia state park system Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 10 1–11

T. C. Huan J. Beamon L. Shelby (2002) ArticleTitleUsing action-grids in tourism management Tourism Management 23 255–264 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00087-5

J. Kline D. Wichlens (1998) ArticleTitleMeasuring heterogeneous preferences for preserving farmland and open space Ecological Economics 26 211–224 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00115-8

Kreag, G. 2002. Duluth values open space. University of Minnesota Sea Grant Program Publication T14, 17 pp

J. Loomis K. Traynor T. Brown (1999) ArticleTitleTrichotomous choice: a possible solution to dual response objectives in dichotomous choice contingent valuation questions Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 24 572–583

L. Lynch W. N. Musser (2001) ArticleTitleA relative efficiency analysis of farmland preservation programs Land Economics 77 577–594

J.A. Martilla J. C. James (1977) ArticleTitleImportance-performance analysis Journal of Marketing 41 77–79

M. McCurdy L. McClure (2002) ArticleTitleLand at risk: Partnerships produce “greenprint” survey for Illinois Illinois Parks and Recreation 33 24–27

McDonald, C.A., C. A. Miller, and W.P. Stewart. 2003. Public perceptions of open space in Illinois. Report to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. University of Illinois and Illinois Natural History Survey

Mengak, K. K. 1985. Use of importance-performance analysis to evaluate a visitor center. MS thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina

H. Oh (2001) ArticleTitleRevisiting importance-performance analysis Tourism Management 22 617–627 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00036-X

T. A. Tannery (1987) ArticleTitlePublic opinion and interest group positions on open-space issues in Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA: Implications for resource management Environmental Management 11 369–373 Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF01867165

The Trust for Public Land. 2002, November 5. Americans approve $2.9 Billion for open space. Retrieved from http://www.tpl.org/tier3_cd.cfm?content_item_id=10925&folder_id=186

The Trust for Public Land, Chesakpeake Bay Foundation, and The Nature Conservancy Action Fund. 2001. Executive Summary of the Statewide Virginia Voter Survey

M. R. Thomas (2003) ArticleTitleThe use of ecologically based screening criteria in a community-sponsored open space preservation programme Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 46 691–714 Occurrence Handle10.1080/0964056032000138445

United States Census Bureau. 2000. http://www.census.gov/census2000/states/il.htm/

G. Wolfram (1981) ArticleTitleThe sale of development rights and zoning in the preservation of open space: Lindahl equilibrium and a case study Land Economics 57 398–413

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided through the Illinois Natural History Survey by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and the Illinois Association of Parks Districts. At the time of data collection and analysis, the fourth author was employed by the Illinois Natural History Survey. We thank the three anonymous reviewers for their comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Backlund, E.A., Stewart, W.P., McDonald, C. et al. Public Evaluation of Open Space in Illinois: Citizen Support for Natural Area Acquisition. Environmental Management 34, 634–641 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0015-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0015-z