Abstract

Background

The understanding of facial anatomy and its changes through aging has led to the development of several different facelift techniques that focus on being less invasive and traumatic and, at the same time, providing natural long-lasting results. In this article we describe step by step our facelift technique as it has been done over the past 10 years by the senior author.

Methods

This is a retrospective, descriptive, transversal study in which all patients who underwent a rhytidectomy using our technique from January 2002 to September 2012 were included. All patients were operated on under local anesthesia and superficial conscious sedation. All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon. A complete step-by-step description of the surgical technique can be found in the main article.

Results

Between January 2002 and September 2012, a total of 113 patients underwent facelift surgery. Of these, 88.9 % were women and 11.1 % were men. The mean age was 55.3 (±8.66) years. Primary surgeries represented 80.3 % (n = 94), secondary 18.8 % (n = 22), and tertiary 0.85 % (n = 1). Only one major complication, representing 0.8 %, consisting of a right-sided temporal paresis with 2 months complete recovery was seen. The minor complications rate was 23.1 %. The most common minor complication was hypertrophic/keloid scars which made up 77.8 % of all minor complications.

Conclusions

The technique described provides good and long-lasting aesthetic results with shorter scars, smaller areas of dissection (without temporal and postauricular flaps), and a shorter recovery period.

Level of Evidence V

This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors http://www.springer.com/00266.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Facelift surgery continues to be a controversial subject because there is no “ideal” surgical technique [1]. This has led to the development of several different techniques that focus on being less invasive and traumatic and, at the same time, providing natural long-lasting results.

The understanding of facial aging needs an anatomical and physiological analysis [2]. Skin flaccidity produced by time, sun exposure, and social habits as well as the hypotrophy of the subcutaneous tissue and fat modifies the facial contour. These changes do not occur in a single gravitational vector [3] but along several vectors created by the different fascia attachments and anatomic orifices of the skull. The skin behaves like the face muscles, which have different vectors of contraction/relaxation producing the corresponding skin wrinkles perpendicular to their axis.

Rhytidectomy techniques have been evolving substantially as a result of improvements in the understanding of facial aging. Passot [4] used a small “s”-shaped preauricular incision to treat facial wrinkles. Bettman used a continuous incision, similar to the one we use now, in the classic technique described in his famous 1920's book Plastic and cosmetic surgery of the face. Skoog developed the concept of skin resection to treat excess flaccid skin technique described in 1974 in his book Plastic Surgery: New methods and refinements.

The description of the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS) by Mitz and Peyronie [5] generated new ideas to provide better aesthetic and long-lasting results. The aging characteristics generated by gravity were corrected by releasing the SMAS attachments and repositioning them, obtaining the features of a younger face [6–8]. However, many of these new techniques require deep dissection, which generates more trauma, higher morbidity, and longer recovery periods [9, 10].

SMAS repositioning has been done in several different ways. Saylan [11], for example, fixed the SMAS by suturing it to the zygomatic arch periosteum through the “s”-shaped preauricular incision described by Passot. He did it in an area called “no man’s land.”

Baker [12] describes a rhytidectomy using shorter incisions associated with a lateral SMASectomy, direct suture without SMAS dissection, and with a temporal flap.

With these techniques, the elongation of the inferior eyelid, reduction of malar eminence, and loss of volume of the submalar area and mandibular prominence were greatly resolved. The nasolabial fold had suboptimal results because the facial fat was treated as being part of the SMAS and was not considered a different facial structure. Newer techniques proposed repositioning of the SMAS as well as the facial fat [13]. In the composite rhytidectomy proposed by Hamra [14], the platysma muscle, the malar fat, and orbicularis oculi muscle are repositioned to obtain the desired effect. It is important to mention that in Pitanguy’s 30-year rhytidectomy experience, where he proposes SMAS plicature, round-lift technique and points out the direction the SMAS and facial flap traction should have, he is able to obtain results comparable to those in which the SMAS was elevated [15, 16].

The knowledge obtained over the years as well as the need to offer natural results with shorter scars, less dissection/traumatized areas, and shorter recovery periods motivated us to develop the technique presented here. In this article we describe it step by step, as it has been done over the past 10 years by the senior author.

Method

This is a retrospective, descriptive, transversal study in which all patients who underwent a rhytidectomy using our technique from January 2002 to September 2012 were included. Information obtained from the medical records included age, sex, whether it was a primary or secondary procedure, type of SMAS plication, complications, and photographic follow-up. All patients were operated on under local anesthesia and superficial conscious sedation. All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon.

Surgical Technique

Evaluation of facial movement and determination of the traction vectors are done with the patient in the prone position before surgery. The six traction vectors are determined and drawn on the skin (Fig. 1). These vectors are malar, nasolabial fold, labial commissure, mandibular border, cervical, and brow. No hair trimming is performed. The limited area of undermining is marked with methylene blue as well as the pre- and post-auricular incisions (Fig. 2). Local anesthesia, consisting of NaCl 0.9/00 + lidocaine 0.35 % + adrenaline 1:200,000 + Na bicarbonate, in a volume of 40–50 cc per each side is infiltrated.

The surgery begins with submental liposuction. For the last 6 years we have incorporated the lipolaser technique (application of subdermal laser to the cervical area followed by lipoaspiration). The laser treatment allows us to limit cervical undermining and to be less traumatizing. The pre- and post-auricular incisions are made, carrying the latter one only halfway up the ear concha (Fig. 3). Subcutaneous/supra-SMAS undermining is performed. The superior limit of the dissection is 2 cm above and parallel to the zygomatic arch, and the medial limit is 2 cm lateral to the nasolabial fold. Inferiorly, the cervical flap is only 3–4 cm below the ear lobule dissected.

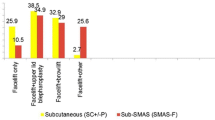

After careful hemostasis, SMAS plication is performed using the vectors of traction previously determined and drawn on the skin for use as a guide. Plication is performed using “U” horizontal 4/0 nylon mattress sutures. The order of plication is as follows: first the malar vector to reposition the malar fat pad, fixing it above the zygomatic arch, followed by the nasolabial fold, labial commissure, mandibular border, and finally the cervical vector. In the cervical area, the lateral border of the platysma is sutured over the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Each plication suture should travel 2.5–3 cm. When necessary, SMAStectomy in the mandibular area is performed. Some accessory sutures are placed in between the ones described for a better accommodation of the SMAS. Normally, there is no need for any fat trimming because, if done correctly, the plication sutures provide good tissue positioning.

Skin traction is performed as described by Pitanguy [15] in his round-lifting technique. It is extremely important not to leave any tension on the skin as this will result in face-lifting stigmas. During this traction, no elevation of the sideburn should be seen. The skin fixation begins with point A (Fig. 4), located at the superior angle of the tragus where it joins the helix. Temporary fixation is done with a 3/0 nylon suture. Next, the ear lobule is fixed in position to the cervical flap with a subdermal absorbable 4/0 suture and a 5/0 nylon suture at skin level (Fig. 5). The cervical traction is performed, sweeping the flap toward the retroauricular fascia concha, and fixed halfway up the auricular concha with one 4/0 absorbable suture (point B) (Figs. 4, 6). An extra subdermal absorbable 4/0 stitch is placed between the ear lobule and point B (Fig. 7). Excess skin is then trimmed away in the pre- and postauricular and cervical areas. In the postauricular area, a “V”-shaped incision is made in the most superior part of the incision only if a “dog’s ear” appears. Skin is closed with 4/0 nylon sutures (Figs. 8, 9). In the preauricular area, the flap is thinned with fine Iris scissors to eliminate any rough transitions between the ear and flap. A 4/0 absorbable subdermal suture is placed in the pretragus area to anchor the flap. Skin is closed with a simple 5/0 nylon suture. Temporal anchoring sutures are removed. A suction drain is placed at both sides. Afterward, to treat the sixth vector, the lateral brow lift is performed [17].

Finally, fat grafting is performed using microcannulas. In general, the grafted areas are the nasolabial fold (1.5 cc per side), marionette lines (1 cc per side), and the nasojugal fold and infraorbital area (2–2.5 cc). No infiltration of anesthetic solution is done since the patient is under IV sedation. By not using local infiltration, we do not alter the patient’s features and the treatment result can be estimated accurately. We have been doing fat grafting with more frequency now since we are able to obtain better adipose cell survival using the 1,210-nm wavelength laser.

In the immediate postoperative period, a compressive elastic garment is placed with gauze filled with NaCl ice crushed inside. Compression is left for 24 h as well as the suction drains. Lymphatic drainage starts on postoperative day (POD) 5 until POD 10. No antibiotic prophylaxis is administered and postoperative analgesia is given as indicated.

Results

Between January 2002 and September 2012, a total of 113 patients underwent facelift surgery as described above. Of these, 88.9 % were women (104) and 11.1 % were men [13]. The mean age was 55.3 ± 8.66 years (70 % of the patients were between 41 and 81). Primary surgeries were 80.3 % (n = 94), secondary 18.8 % (n = 22), and tertiary 0.85 % (n = 1).

There was only one major complication (0.8 %), a right-sided temporal paresis that completely resolved in 2 months. No skin necrosis or alopecia was observed. Minor complications were seen in 23.1 % of the patients (n = 27). The most common minor complication was hypertrophic/keloid scars which were 77.8 % (n = 21) of all minor complications. Only six patients (5.3 %) required surgical revision of their scars. Other minor complications were seroma [7.4 % (n = 2)], hematoma [7.4 % (n = 2)], and skin epidermolysis [7.4 % (n = 2)]. Mean recovery time was 14 (± 4.2) days. Pre- and postoperative photos are shown in Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13.

Discussion

Numerous techniques have been described for the treatment of facial aging. These techniques have to deal with complex and multiple aging characteristics such as fat atrophy and redistribution, bone resorption, flaccid skin, and the gravity effect [19]. All techniques offer good results when performed by experienced surgeons. However, there are several differences between them, including the size and shape of the incision, extent and depth of dissection, SMAS and platysma treatment, and the direction of skin traction.

In general, the more we extend and deepen the dissection during the surgery, the more we have an increased risk of morbidity as well as extended recovery time (i.e., return to normal daily activities). Most of our patients prefer a less invasive procedure with less probability of complications and a quick recovery period. At the same time, they want natural-looking long-lasting results without any stigmas. There have been several surgeons who have proposed less invasive techniques [12, 20]. Having smaller incisions is particularly important in South America (Peru) because mestizo-type skin (Fitzpatrick IV–V) has a higher probability of developing hypertrophic or keloid scarring. In our technique, the length of the incision is 45 % smaller than that in Pitanguy’s round block technique [15]; this is done by avoiding the cervical hairline, postauricular, and temporal incisions. We consider that the intracapillary incision does not provide any advantages in the cervical treatment but allows only skin placement, a concept that we share with Tonnard and Verpaele [20, 21]. The excess skin can be situated in the retroauricular sulcus. The little wrinkles disappear in the following weeks.

The incision in the temporal area is limited to about 2 cm, enough to treat the “dog’s ear” that forms. The treatment of the lateral periocular and lateral upper third is accomplished by the lateral brow technique [17], avoiding the temporal flap.

We do not use prehairline temporal incisions. Although they have been used by several authors with good results, we believe that in our patients they are not the best choice because of the high incidence of bad scarring. We also believe that pure vertical vectors of traction can cause a flattening of the preparotid area, an area that has already suffered atrophy due to aging [22]. We propose that a lateral oblique vector instead of a pure vertical one is better to achieve more natural results. There are articles that support that this type of traction repositions facial tissue such that it resembles how it was when the patient was younger [16, 23].

We believe that besides gravity, facial expressions (facial muscle vectors) over the years, influenced by the natural orifices of the skull, contribute to the rearrangement of tissue. In recent research, magnetic resonance imaging was used to evaluate the relative contribution of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscles to the formation of the nasolabial fold while smiling and at rest. It was found that there is a thickening of the inferior region of the malar fat and an expansion of the skin around the same area without changes in the levator muscles of the lip [24]. During smiling, there is a shortening of the levator labial commissure that produces pressure over the malar fat and the skin inferior to the cheek. Over time, this produces a redistribution of fat and flaccid skin. This explains why when the malar fat is lifted, the nasolabial fold improves dramatically [25]. That is why we prefer to apply several different vectors of traction when treating the SMAS, starting at the malar area. We do not consider it necessary to undermine it because the malar fat plication makes it slide above the SMAS without any restriction in the suprazygomatic direction. It is extremely important to determine this vector in the preoperative period.

The platysma is treated by traction of its lateral border and fixing it to the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the postauricular area. We prefer not to perform extensive undermining because we believe that the tunneling of the liposuction is enough to provide good traction. The use of the 1,210-nm wavelength laser has allowed us to perform smaller areas of dissection, advancing only 3 cm from the ear lobule. Laser treatment also favors skin retraction due to the stimulation of collagen production [18, 26–28].

We believe that besides the surgical technique used, the surgeon’s experience and artistic sensibility has a lot of influence on the results obtained [29]. If the techniques provided similar results, we should prioritize on the side of a patient’s security by being less invasive and therefore reducing complications. By performing less invasive surgeries we also provide shorter recovery periods.

Conclusion

The technique described here provides good and long-lasting aesthetic results with shorter scars, smaller areas of dissection (without temporal and postauricular flaps), and a shorter recovery period. It is important to mention that the technique has to be associated with the lateral brow-lift technique [17], which allows treatment of the periorbital and temporal areas. We also recommend the use of assisted liposuction with the (intradermal) 1,210-nm laser in the cervical area that produces skin retraction resulting in a smoother cervical and mandibular contour. The ideal patients for this technique are younger (45–55 years old) and secondary cases in which less skin needs to be excised. In patients with severe skin flaccidity, the traditional technique with the temporal flap should be used. The use of fat grafting is an excellent option for the finishing details in terms of volume reposition and facial grooves.

References

Waterhouse N, Vesely M, Bulstrode NW (2007) Modified lateral SMASectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 119(3):1021–1026

Mentz HA III, Patronella CK (2005) Facelift: measurement of superficial muscular aponeurotic system advancement with and without zygomaticus major muscle release. Aesthet Plast Surg 29(5):353–362

Stocchero IN (2007) Short scar face-lift with the RoundBlock SMAS treatment: a younger face for all. Aesthet Plast Surg 31(3):275–278

Passot R (1919) La chirurgie esthetique des rides du visage. Presse Med 27:258

Mitz V, Peyronie M (1976) The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast Reconstr Surg 58(1):80–88

Mendelson BC (2001) Surgery of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system: principles of release, vectors, and fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg 107(6):1545–1552

Stuzin JM, Baker TJ, Gordon HL (1992) The relationship of the superficial and deep facial fascias: relevance to rhytidectomy and aging. Plast Reconstr Surg 89(3):441–449

Teimourian B, Delia S, Wahrman A (1994) The multiplane face lift. Plast Reconstr Surg 93(1):78–85

Baker TJ, Gordon HL (1967) Complications of rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 40(1):31–39

Matarasso A, Elkwood A, Rankin M, Elkowitz M (2000) National plastic surgery survey: face lift techniques and complications. Plast Reconstr Surg 106(5):1185–1195

Saylan Z (1999) The S-lift: less is more. Aesthet Surg J 19(5):406–409

Baker DC (2001) Minimal incision rhytidectomy (short scar face lift) with lateral SMASectomy: evolution and application. Aesthet Surg J 21(1):14–26

Noone RB (2006) Suture suspension malarplasty with SMAS plication and modified SMASectomy: a simplified approach to midface lifting. Plast Reconstr Surg 117(3):792–803

Hamra ST (1992) Composite rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 90(1):1–13

Pitanguy I, Radwanski HN, De Amorim NF (1999) Treatment of the aging face using the “round-lifting” technique. Aesthet Surg J 19(3):216–222

Pitanguy I, Machado BH (2012) Facial rejuvenation surgery: a retrospective study of 8788 cases. Aesthet Surg J 32(4):393–412

Centurión P, Romero C (2010) Lateral brow lift: a surgical proposal. Aesthet Plast Surg 34(6):745–757

Centurion P, Noriega A (2013) Fat preserving by laser 1210-nm. J Cosmet Laser Ther 15(1):2–12

Coleman SR, Grover R (2006) The anatomy of the aging face: volume loss and changes in 3-dimensional topography. Aesthet Surg J 26(1 Suppl):S4–S9

Tonnard P, Verpaele A, Monstrey S, Van Landuyt K, Blondeel P, Hamdi M et al (2002) Minimal access cranial suspension lift: a modified S-lift. Plast Reconstr Surg 109(6):2074–2086

Verpaele A, Tonnard P (2008) Lower third of the face: indications and limitations of the minimal access cranial suspension lift. Clin Plast Surg 35(4):645–659

Stuzin JM (2007) Restoring facial shape in face lifting: the role of skeletal support in facial analysis and midface soft-tissue repositioning (Baker Gordon Sympsium Cosmetic Series). Plast Reconstr Surg 119(1):362–376

Pitanguy I, Pamplona DC, Giuntini ME, Salgado F, Radwanski HN (1995) Computational simulation of rhytidectomy by the “round-lifting” technique. Rev Bras Cir 85:213–218

Gosain AK, Amarante MT, Hyde JS, Yousif NJ (1996) A dynamic analysis of changes in the nasolabial fold using magnetic resonance imaging: implications for facial rejuvenation and facial animation surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 98(4):622–636

Owsley JQ, Roberts CL (2008) Some anatomical observations on midface aging and long-term results of surgical treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 121(1):258–268

Goldman A (2006) Submental Nd:Yag laser-assisted liposuction. Lasers Surg Med 38(3):181–184

Badin A, Moraes L, Gondek L, Chiaratti M, Canta L (2002) Laser lipolysis: flaccidity under control. Aesthet Plast Surg 26(5):335–339

Centurión P, Cuba JL, Noriega A (2011) Liposucción con diodo láser 980-nm (LSDL 980-nm): optimización de protocolo seguro en cirugía de contorno corporal. Cir Plást Ibero-Latinoam 37(4):355–364

Alpert BS, Baker DC, Hamra ST, Owsley JQ, Ramirez O (2009) Identical twin face lifts with differing techniques: a 10-year follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg 123(3):1025–1033

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no financial relationships with commercial interest(s) that produce healthcare products or services discussed in the article as well as any relationships or activities that present a potential conflict of interest. All authors declare that they have no commercial interest in the subject of study and the source of any financial or material support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Centurion, P., Romero, C., Olivencia, C. et al. Short-Scar Facelift without Temporal Flap: A 10-year Experience. Aesth Plast Surg 38, 670–677 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-014-0350-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-014-0350-2