Abstract

Midface rejuvenation surgery is most challenging. The margin of error for the lower lid is on the order of 0.5 mm, and the cosmetic result can sometimes look unnatural. A minimally invasive technique for malar and lower lid lift is proposed. Two incisions are used: the standard subciliary lower eyelid incision and one on the lateral part of the upper eyelid. Through these incisions a skin flap lower eyelid dissection and a subperiosteal malar dissection are performed. The arcus marginalis itself is not transected as is the case when the malar area is entered from the lower eyelid. Rather, a subperiosteral release of the arcus marginalis is performed through a muscle-splitting incision at the lateral canthus. Eyelid malposition is avoided because the muscles, vessels, and nerves converging toward the medial canthus are not interrupted. The subperiosteal dissection of the arcus marginalis extends to the medial canthus and also releases the insertion of the orbicularis oculi superior malar part. Consequently, all the attachments of the tear trough are released. Two subperiosteal suspensions connect the central part of the nasolabial volume and, more laterally, the central part of the malar area to the inferolateral orbital rim. The elevation of the malar volume resulting from these suspensions is concentric with the orbit. A final third suspension vertically connects the orbicularis oculi muscle with the underlying periosteum to the bone of the lateral orbital rim. Significant skin excess is removed from the lower eyelid. Complete disinsertion of the tear trough attachments combined with the malar elevation treats the entire palpebromalar groove. The lifted fat volume fills the space resulting from the subperiosteal disinsertion. A safer, more natural and more reliable result is achieved because the vectors of traction with this technique are exactly opposite those of the midface aging process, and because a very stable fixation is created between the lifted malar periosteum and the malar and latero-orbital rim bones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Malar and the Lower Eyelid Aging Process

Rejuvenation of the lower lid must include the periorbital area to achieve a harmonious midface rejuvenation. As part of the aging process, the junction between the lower lid and cheek develops into a nasojugal or tear trough depression [4] medially and a palpebromalar groove [9] laterally.

The aging process of the anterior malar area is linked in large part to the presence and function of the levator muscles of the upper lip because as the malar fat pad does not have a direct connection with these muscles and descends with time. As a direct result of this descent, the nasojugal or tear trough depression above and the underlying nasolabial fold progressively develop. The rejuvenation vector must be perpendicular to these folds to restore the malar fat pad at its original location (Fig. 1).

Concentric malar lift performed with two suspensions through points B and C. Point B is the vertical anchor of the malar volume B1 (lateral part of the malar fat pad) at the same horizontal level as C1, which is lateral to the vertical line passing through the lateral canthus bone insertion. Point C is the anchor through the inferior orbital rim lateral part of the nasolabial volume C1 (malar fat pad).

The aging process of the periorbital contour is caused largely by the action of the malar part of the orbicularis oculi muscle (Fig. 2). During orbicularis contraction, the malar soft tissues move both medially and superiorly. Specifically, (the superior malar part of the orbicularis muscle is the most mobile and most effective part of the orbicularis in causing the oblique (vertical and medial) movement of the lower eyelid. This oblique translation stops at the medial canthus, as shown by the lack of wrinkles there (Fig. 2, area 3). The medial insertion of this superior malar part of the muscle is on the bone at the medial canthus.

Left: lower eyelid at rest. Right: eyelid with forced orbicularis oculi muscle contraction. Segment 1 is the superior malar part of the orbicularis oculi muscle supported by the inferior orbital rim when it is contracting. The wrinkling stops at point 3. Segment 2 is the inferior orbital part of the orbicularis oculi muscle at the superior orbital rim (the superior orbital part is concerned with eyelashe position) supported by the superior orbital rim when it is contracting. The contraction of these two muscle parts creates two symmetric furrows. The furrow at the medial lower eyelid is the tear trough. Area 3 is the bone insertion of these two converging muscles, medial to the medial canthal tendon.

The contraction of the orbicularis oculi superior malar part presses the soft tissue against the inferior orbital rim (Fig. 3). During relaxation of the muscle, the malar tissues descend. Over time, the resting position of the malar tissues becomes progressively lower. The location of fat in relation to the orbicularis oculi (both superficial and deep) is progressively moved around the orbital contour in a centrifugal way.

The two key attachments of the orbicularis pertaining to the tear trough. (1) Insertion of the septal part of the orbicularis oculi muscle at the medial extremity of the inferior orbital rim. (2) Insertion of the superior malar part of the orbicularis oculi muscle medial to the medial canthal tendon. Release of the arcus marginalis and these medial muscle insertions fade the tear trough. Concerning the upper eyelid, the permanent contraction of the inferior orbital part of the orbicularis oculi muscle, inserted 2 is responsible for a trough symmetric to the tear trough in the lower eyelid. (O.O.S.M.P.: orbicularis oculi superior malar part).

The tear trough depression and the palpebromalar groove appear at the junction between the lower eyelid and the cheek [8]. Over time, the skeletonization of the orbital rim contour becomes more prominent and lower [5]. More precisely, the semicircular aging process is excentric. The usual vector used in rejuvenation surgery of the periorbital contour is upward and lateral, toward the temple. Consequently, the malar volume is transposed toward the temple, resulting in an unnatural appearance because the malar volume does not originate in this area [10].

In fact, to be most effective, the vector of rejuvenation must be perpendicular to the furrow resulting from the aging process. The vectors for rejuvenation of the tear trough and palpebromalar groove should converge to a point near the pupilla (Fig. 4). If this could be replicated surgically, the result achieved would be more natural because each of the ptotic volumes would be restored to its original location, and the anterior malar volume, particularly, would be lifted to fill the tear trough.

The aging process of the lower eyelid is attributable primarily to the action of the septal part of the orbicularis oculi muscle. During muscle contraction, the septal part of the lower eyelid is transposed upward and medially. The vector of rejuvenation of the lower eyelid must be perpendicular to this direction, from the lateral canthus. If the vector of traction is applied to the lid 3 mm inside the lateral extremity of the eyelid margin, this traction recreates the young subtarsal fold (Fig. 5).

Tear Trough Anatomy

Anatomic dissections demonstrate that tension applied laterally to the orbicularis oculi after malar subperiosteal dissection does not reduce the depth of the tear through (Fig. 6). Two additional components must be specifically released to allow the tear trough to be smoothed out when the orbicularis oculi muscle is tightened laterally.

The first element is the arcus marginalis, which must be released from its inferior orbital rim attachment, from the lateral canthus to the medial canthus. This also releases the medial insertion of the septal part of the orbicularis oculi muscle (Figs. 7 and 8).

The second element is the medial insertion of the superior malar part of the orbicularis oculi (Fig. 9). The superior malar part of the orbicularis oculi is the section of the muscle sustained by the inferior orbital rim when it is contracting at a forced squint. The bone insertion of this part of the muscle is immediately medial to the medial canthal tendon (Fig. 2).

The inner part of the upper eyelid also has a furrow corresponding to the lower eyelid tear trough. This furrow deepens at forced contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle on the upper eyelid. Forced contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle converges to the same insertion location, medial to the medial canthus, as does the superior malar part of the orbicularis oculi muscle (Fig. 3). Correction of the lower eyelid tear trough can be associated with correction of the upper eyelid groove, resulting in a harmonious eyelid rejuvenation.

Fortunately, experience has shown that the release of these two insertions (the arcus marginalis and the superior malar part of the orbicularis oculi does not lead to complications. The purpose of this release (Fig. 10) is to allow for the elevation of the entire lower eyelid and the entire malar fat pad volume (medial and lateral) with the two concentric suspension sutures (Fig. 1). Because of the detachments, the volume is able to fill the tear trough and the palpebromalar groove.

Preoperative Considerations and Markings

If a significant skin excess already exists in the crows foot area, the malar suspensions and the orbicularis oculi muscle suspension further increase this temporal excess of skin. Therefore, a temporal lift is needed to redrape this excess of skin. This temporal lift is achieved by the temporal part of the mask lift using Tessier’s [11] technique, without skin excision. A temporal dissection usually is not necessary for middle-aged patients undergoing a midface rejuvenation.

The first marking is a semicircular line located at the deepest part of the tear trough and palpebromalar groove (Fig. 4). The dissection of the lateral skin flap will stop at or above that level depending on the amount of excess skin to be removed. The second marking is point C1 overlying the center of the prominence of the nasolabial fullness (Fig. 11). The third marking is the classical malar point B1 at the intersection between the projections from the nasal alar and the lateral canthus [7]. Other preoperative markings are the same as for a standard blepharoplasty.

Entrance with a straight needle at point C1 directed toward point C, located on the inferior orbital rim. The infraorbital nerve (ION) is more medial, indicated with a thin needle in the infraorbital opening. There is no risk of entrapping a lateral branch of this nerve. Elevation of the malar fat pad volume is mandatory for filling of the free space resulting from disinsertion of the tear trough attachments.

Surgery

Subcutaneous Dissection

Dissection through the subciliary lower eyelid incision is subcutaneous as far as the level of the new subtarsal fold. The extent of subcutaneous dissection extends laterally part way or all the way to the palpebromalar groove depending on the amount of excess skin present in the lower lid. The amount of skin to be removed is calculated by a pinch test below the lateral canthus using moderate tension with a smooth forcep. The upper edge of the forcep is placed at the lateral canthus and the lower edge on the skin at point A1 (Fig. 5).

Subperiosteal Dissection

The subperiosteal dissection of the malar area is performed through the upper eyelid incision extending onto the inferior orbital rim (Fig. 12). This subperiosteal dissection of the orbital rim must be only 1 cm wide to avoid damaging the zygomaticofacial nerve.

Cadaver dissection (right side, viewed from above). (A) Subperiosteal dissection of the malar area through the lower eyelid. Point M is the middle of the inferior orbital rim. (B) Malar fat pad suspension at C1 toward C. The disinserted tear trough area is to be filled with the elevated malar fat volume. (C) Malar volume suspension at B1 toward B. The disinserted arcus marginalis area is filled with the elevated malar fat volume. The palpebromalar groove is faded

A 1-cm incision is made through the orbicularis at the lateral canthus level, just below and parallel to the lower lid skin incision. Through this incision, the entire malar area is dissected subperiosteally. This dissection must avoid damage to the zygomaticofacial nerve, which is dissected easily under direct vision, and also the infraorbital nerve. A thin needle is entered through the skin in the infraorbital opening to locate the origin of the nerve. The extent of the dissection laterally involves the body of the zygoma (dissection of the zygomatic arch is not needed), inferiorly involves the inferior border of the zygoma and the pyriform aperture, and medially involves the nasal bone after release of the arcus marginalis and the medial insertion of the superior malar part of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The release of the medial part of the arcus marginalis must avoid the lacrimal sac. It is not necessary to dissect intraorbitally in this area. However, dissection is 1 cm intraorbitally along the lateral and inferior orbital rim for performance of the orbital rim suspension. The use of a retractor to check the disinsertion of the levator labii Superioris muscle is mandatory. Otherwise the contraction of this muscle would push down the underlying lifted malar fat pad. Traction with a hook confirms the adequacy of the release and the lift of the dissected malar volume with the suborbicularis oculi fat [1].

Two holes are drilled through the lateral orbital rim and one through the inferior orbital rim. The first hole (A) is placed above the lateral canthus, at the junction between the orbital rim and continuation of the line of the concave margin of the lateral lower eyelid margin. This hole is created to suspend the orbicularis oculi muscle and the underlying periosteum (Figs. 1 and 13A). The second hole (B), placed at the junction of the lateral and inferior orbital rim, is used to perform the vertical malar suspension (Fig. 13B).

Drill holes through oribital rim. (A) Lateral orbital rim, above the lateral canthus. (B) Lower part of the lateral orbital rim. (C) Lateral part of the inferior orbital rim as the basis for stable suspensions. A 1-cm muscle opening at the lateral canthus is sufficient for drilling the inferior orbital rim, thanks to the tissue laxity.

A third hole (C), placed at the junction of the medium third and lateral third of the inferior orbital rim, is used for the nasolabial suspension (Fig. 13C).

Suspension Sutures

Nasolabial Volume Suspension Suture

For nasolabial volume suspension suture, (Figs. 1 and 11) a straight needle is used. The entry point (C1) of the needle is through the skin overlying the center of the nasolabial fullness, lateral to the infraorbital nerve. The needle entrance is facilitated by a 2-mm stab incision made with a number 11 scalpel blade, which does not leave a visible scar. The needle goes deeply through the periosteum, and then is directed upward, perpendicular to the axis of the nasolabial fold. It exits through the muscle opening to be threaded with the end of a 3/0 Prolene suture previously passed through the bone at point C. The needle then descends to the level of point C1 and, without exiting the skin completely, is redirected upward toward point C at a more superficial level. Accordingly, the double pass of the needle grasps the full thickness of the nasolabial mass.

Once the needle has been returned to the level of the bone hole, the end of the suture is removed from the needle and tied under moderate tension. The knot is positioned inside the bone to keep it from becoming palpable. The elevation of the medial malar fat pad combined with the tear trough disinsertion decreases the depth of the tear trough.

Vertical Malar Suspension Suture

The axis of this suspension is slightly oblique medially, making it perpendicular to the orbital rim at the point B level. The medial oblique direction of this vector minimizes the appearance of a lateral skin excess. Point B1 is at the same horizontal level as C1 and 3 mm lateral to a vertical line passed down from the lateral canthus (bony rim insertion).

The suspension between points B and B1 is performed through the muscle opening, under direct vision without a skin incision (Fig. 1).

Vertical Orbicularis Oculi Muscle and Periosteum Suspension

For this procedure (Figs. 5 and 14), a 3/0 Prolene suture is passed through the bone at point A, then along the lateral orbital rim, on the bone, to exit through the muscular opening at the lower eyelid. It is important to note that the subperiosteal dissection performed in the malar area near the lateral orbital rim should elevate all the periosteum. This allows a strong adhesion between the elevated orbicularis oculi muscle with its underlying periosteum and the bone, which is necessary for the long-term stability of this lateral elevation. This technique has been used by Besins [3] with the RARE (Reverse and Repositioning Effect) technique. Failure to remove the periosteum from the bone predisposes the procedure to secondary slipping of the muscle with loss of the skin tension of the lower eyelid

Lateral orbicularis oculi muscle (with its periosteum) suspension is performed with a 3/0 Prolene suture passing through the lateral orbital rim at A, then going to A1 to suspend the muscle and the periosteum with a U-shaped pass. At the top of the triangular muscle flap, the thread then makes a loop to lift this triangular flap and finally returns to A. When the thread is tightened, the muscle flap is pressed on to the bone to favor its adhesion. A1 elevation tenses the whole malar area.

The suture is then passed through the periosteum and the orbicularis muscle from deep to superficial near the inferior border of the muscle flap (point A1). Next, the suture is returned through the muscle and the periosteum, and another suture bite is taken through the muscle near the top of the triangular muscle flap. The suture is returned along the orbital rim to exit at point A. The benefit of this tension on the lower lid is tested before the suture is tied. The vertical and triangular orbicularis oculi muscle flap is spread accordingly onto the bone at the lateral orbital rim. The position of the new subtarsal fold ( point A1) must be 3 mm below the lash line.

Skin Excision

Excision of skin usually is important, even if only a minor excess is present before the surgery. This is because the elevation of the malar volume and the vertical orbicularis oculi muscle suspension create a vertical excess of skin. The skin excision is particularly safe, thanks to the stability of the muscular and periosteal suspensions. These suspensions are secured by the strong adhesions between the elevated periosteum and the malar bone. A slight overcorrection of elevation is performed, and the excess of skin is removed with moderation. Although the amount of skin removed using this technique is more than usual, it still must be undertaken with great care. The subtarsal fold created by the tension on the orbicularis oculi muscle at that level (3 mm under the eyelashes) is stable and reduces the risk of ectropion. Sufficient skin must be left between the fold and the eyelashes (3-4 mm).

Clinical Material

This study analyzed 67 patients who underwent concentric malar lift with lower eyelid and malar rejuvenation (Figs. 15, 16, and 17). Of these patients, 52 also had upper eyelid surgery and 45 underwent a facelift during the same operative procedure. Only five of these patients underwent canthopexy to achieve a more lateral position of their canthus (almond-shaped eye), and none underwent the procedure to secure the elevation of the lower eyelid. Surgery was performed to elevate the eyelash’s level for 7 of the patients because previous standard lower eyelid surgery had caused a descent of this line.

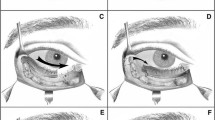

(A, B, C) A 54-year-old patient with a low positioned lower eyelid associated with a tear trough deformity and a palpebromalar fold. (D, E, F) Appearance 4 months after a concentric malar lift associated with a lower facelift, an upperlip lift, and nasal tip elevation. The upper lid has been improved with the suture of the periorbital fat on the superior periorbital rim. The lower eyelid position is elevated, and the palpebromalar groove and tear trough are improved. No canthopexy or fat reinjections were performed. The result appears natural because the inferior periorbital contour is rejuvenated exactly the opposite of the aging process.

(A, B, C) A 34 years-old patient with a low positioned lower eyelid associated with a tear trough deformity and a palpebromalar groove. She had undergone two previous lower lid blepharoplasties. (D, E, F) Appearance 5 months after a concentric malar lift and a lateral canthopexy. The entire lower eyelid is elevated. The tear trough and the palpebromalar groove are improved. No fat was reinjected, and no lower eyelid skin grafting was performed.

(A, B, C) A 49-year-old patient who underwent a face-lift and four eyelid blepharoplasties 7 years previously. She was a difficult case because she also had silicone injections in her nasolabial fold and her tear trough, with this pigmentation and this inflammatory reaction. (D, E, F). Aspect 6 months after a new face-lift associated with a concentric malar lift. The nasojugal fold is improved, and the tear trough is lifted and faded. The entire inferior orbital contour is rejuvenated in a natural way. She had no canthopexy or fat injections.

In 1995, first patients underwent surgery using a variation of the current concentric malar technique, with positive results. The current evolution of the technique has been in regular use for 2 years. The patients ages ranged from 30 to 69 years (median, 44 years). This technique was used for 10 men.

General anesthesia was used when a facelift was performed at the same time. Local anesthesia with nerve block and sedation were used in 30% of the concentric malar lift case. General anaesthesia was used for the other 70%.

Discussion

During the concentric malar lift procedure, dimples must be avoided when the sutures are tightened from point C1 and from point B1. The positioning of the suspension sutures must be sufficiently deep and low to lift the deeper tissue near the periosteum primarily and to lift the superficial tissues near the skin only partially.

The loop of suture at C1 could potentially result in paraesthesia caused by compression of lateral branches of the infraorbital nerves. In fact, there are no main branches lateral to the infraorbital nerve at C1. The C1 suspension has not resulted in numbness of the infraorbital nerve territory for any of the patients.

In the authors’ 9 years of experience using these suspensions, with some variations, they have encounted only a few problems. One stitch “slipped,” presumably because the bite was too small. One case of residual lateral excess, more than expected, required a secondary temporal lift. Often the recovery time was longer than for a standard blepharoplasty, and not infrequently, excessive tearing lasted 3 weeks, probably because of nasolacrymal swelling. No patient had chemosis more than 3 weeks, even in cases of associated canthopexy.

Some problems can be minimized with the use of this technique. The arcus marginalis is not incised as with the standard lower eyelid approach [10]. Rather, it is dissected from the lateral canthus opening. The arcus marginalis is elevated gently from the inferior orbital rim. Consequently, the point of convergence for the whole area. (i.e., the medial canthus) is functionally preserved. The medial canthus region is the point of convergence for muscles (only fixed point of the entire orbicularis oculi muscle system), vessels (facial, palpebral arteries, and veins), tears (lacrimal pump), and lymphatics for the palpebral and malar area. The medial canthus also is the junction of the palpebral and the nasal area through the lacrima fossa. Preserving the entire anatomic and functional unit of the eyelid in fact with no dissection going through it is the most effective way to avoid prolonged edema [6] and to prevent secondary eyelid malposition [6]. This is the reason that surgeons such as Hester [6] and Ramirez [10] now recommend no dissection through this area. No secondary eyelid malposition attributable to posterior or medial lamella retraction occurred with the use of the concentric malar lift technique.

The malar area is dissected subperiosteally. Subperiosteal dissection is mandatory because it involves the only dissection plane that does not move over time [11]. Reattachment, after subperiosteal dissection of the malar tissues, to a higher level, thanks to tension applied on A1, is therefore stable. All the other dissection planes over the malar area can relapse with time. Subperiosteal malar elevation permanently transposes all the malar tissues to a higher level without modifying them.

With the standard subperiosteal malar suspension, the SOOF (Sub orbicularis Oculi Fat) is lifted laterally, toward the temporal area [2, 10]. But this fat does not originate from the temporal area. The surgical relocation can result in an unnatural appearance. The centrifugal migration of this fat is caused by orbicularis oculi muscle contractions. Rejuvenation of the lateral part of the orbital contour must be performed with a concentric, and therefore medial, lift of the SOOF, which is achieved with the two suspension sutures, B1 and C1.

The excess of skin in the temporal area resulting from the concentric malar lift is the least possible for the degree of malar elevation regardless which technique is used. When an oblique superolateral vector is used, a larger skin excess results in the temporal region, frequently requiring an associated temporal lift [2, 3].

In cases of patients requesting an almond-shaped eye, a lateral canthopexy frequently is associated with this technique. As stated by Tessier [11], a more extensive intraorbital subperiosteal dissection allows all of the orbital tissues to rotate in a frontal plane in the direction of the lateral canthopexy. A 4/0 Prolene suture joins point A to the lateral extremity of the inferior tarsal cartilage.

Conclusion

Through one upper and one lower lateral eyelid opening, the reported technique combines the following:

-

Subperiosteal tear trough release, with an arcus marginalis and orbicularis oculi muscle (superior malar part) detachment.

-

Concentric malar lift at the orbital rim with two subperiosteal suspensions. The elevation of the full-thickness malar fat pad volume fills the tear trough and the palpebromalar groove.

-

Vertical suspension of the orbicularis oculi muscle and periosteum at the lateral orbital rim.

-

Minimal surgical trauma with no arcus marginalis incision, no risk of lymphatic or neurovascular disruption, and consequently, no risk of secondary lower eyelid malposition.

-

Good stability of the elevation because of the adhesion between the soft tissues and bone.

The reported procedure achieves a more natural rejuvenation because the lower eyelid lift and concentric malar lift act exactly the opposite of the aging process.

References

AE Aiach OH Ramirez (1995) ArticleTitleThe suborbicularis oculi fat pads: An anatomic and clinical study Plast Reconstr Surg 95 37–42 Occurrence Handle7809265

AZD Badin C Casagrande T Roberts et al. (2001) ArticleTitleMinimally invasive facial rejuvenation endolaser midface lift Aesth Plast Surg 25 447–453 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00266-001-0023-9 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MnosVCjsg%3D%3D

T Besins (2004) ArticleTitleThe RARE technique Aesth Plast Surg 28 127–142 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00266-004-3002-0

RS Flowers (1993) ArticleTitleTear trough implants for correction of tear trough deformity Clin Plast Surg 20 403 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:ByyB2M7ns1c%3D Occurrence Handle8485949

ST Hamra (1995) ArticleTitleArcus marginalis release and orbital fat preservation in midface rejuvenation Plast Reconstr Surg 96 354–362 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:ByqA2M%2FisFY%3D Occurrence Handle7624408

TR Hester MA Codner CD Mc Cord (1996) ArticleTitleThe centrofacial approach for correction of facial aging using the transblepharoplasty subperiosteal cheek lift Aesth Surg J 16 51–58

JW Little (2000) ArticleTitleVolumetric perceptions in midfacial aging with altered priorities for rejuvenation Plast Reconstr Surg 105 252 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c%2FptVChtg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10626998

BC Mendelson (2004) ArticleTitleFat extrusion and septal reset in patients with a tear trough triad: A critical appraisal Plast Reconstr Surg 113.7 2122–2113

BC Mendelson A Muzaffar W Adams (2002) ArticleTitleSurgical anatomy of the midcheek and malar mounds Plast Reconstr surg 110 885 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00006534-200209010-00026 Occurrence Handle12172155

OM Ramirez (2001) ArticleTitleFull-face rejuvenation in three dimensions: A “face-lifting” for the new millennium: Subperiosteal endoscopique technique in secondary rhydidectomy Aesth Plast Surg 25 152–164 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s002660010114 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3MzmsVymsA%3D%3D

P Tessier (1990) ArticleTitleLifting facial sous perioste Ann Chir Plast 34 193–197

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Louarn, C.L. The Concentric Malar Lift: Malar and Lower Eyelid Rejuvenation. Aesth Plast Surg 28, 359–372 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-004-0053-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-004-0053-1