Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to quantify the overall burden of orthopaedic gunshot-related injuries at our institution over a four year period. Secondary aims included identifying complications from gunshot-related injuries and the additional burden it places on healthcare services.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted on all patients with gunshot injuries presenting to our hospital’s trauma unit between January 2014 and December 2017. Patient data was recorded, and demographic data, number and type of implants, blood products used, duration of hospital admission, duration of ICU admission, radiological studies performed, and prevalence of complications were analysed.

Results

A total of 1449 patients with a mean age of 28.2 ± 9.7 years (range 2.0–71.0) were included in this study. The majority of these gunshot-related orthopaedic injuries were sustained to the lower extremities and were treated non-operatively. The median duration of hospital stay was 7.0 (IQR 4.0–12.0). The most common complications identified were nerve injury (8.3%), vascular injury (6.5%), fracture-related infection (3.2%), non-union (3.1%), and compartment syndrome (1.6%). The total cost of care was ZAR 53,568,537 (USD 4,320,043) with an average cost per patient of ZAR 37,031 (USD 2986).

Conclusion

This study highlighted the burden of gunshot injuries presenting to our hospital and the strain it places on its healthcare resources. The prevalence of complications was comparable to international studies on the subject. With improved understanding of this burden, more healthcare resources can be allocated to this problem and better prevention strategies can be planned.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gun-related violence represents a large burden on healthcare resources all over the world, with more than 1000 killed and an estimated 2000 people injured every day [1,2,3]. Gun violence is the most common cause of death in homicide cases worldwide [3]. The rate of fatal firearm injuries per country was estimated at 10.2 per 100,000 in South Africa and 23.7 in Colombia (77% of total homicides) compared with just 4.4 per 100,000 in the USA [2]. While Central America, the Caribbean, South America, and Southern Africa are at the epicentre of intentional gun-related violence, most of the research on gunshot-related injuries is conducted in developed countries, such as the USA [2,3,4].

South Africa is ranked as the 11th most deadly country in the world [2], with Cape Town’s homicide rate being particularly high at 41 homicides per 100,000 people being reported in 2010 [5]. In turn, the proportion of deaths attributable to gunshots is estimated to be about 45% [2], and in South Africa, violence is the fifth leading cause of death [4, 5]. Despite having one of the highest burdens of gunshot injuries in the world, relatively few gunshot-related injury studies originate from Southern Africa.

A study, published by Martin et al. in 2017, reported the burden of gunshot-related injuries at Groote Schuur hospital in 2012 [6]. The authors reported that, among 111 patients, 95 patients underwent a total of 135 surgical procedures to a total of more than 306-hours cumulative surgical theatre time. Although there were limitations in calculating the total associated costs of these procedures, the authors estimate a total theatre cost of USD 94,490, with individual patient costs (excluding implants) averaging USD 2940. Very few studies have been done in South Africa despite its perceived high burden of gunshot injuries.

This study aims to quantify the overall burden of orthopaedic gunshot-related injuries at our institution over a four year period. Secondary aims include identifying complications from gunshot-related injuries and the additional burden it places on healthcare services.

Methods

A retrospective review of clinical records and serial radiographs of all patients presenting with gunshot-related injuries to the extremities, pelvis, and spine between January 2014 and December 2017 was performed. Institutional ethics approval and hospital board approval were obtained prior to commencing data collection.

All adult and paediatric patients presenting to our level 1 trauma unit with a gunshot injury requiring orthopaedic assessment were considered for inclusion. Patients with incomplete documentation were excluded. Data pertaining to patient demographics; injury characteristics; treatment variables including, duration of hospital stay, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), and length of stay; number and type of radiological procedures performed; blood products used; surgical procedure performed; surgical implants used; and any complications experienced was collected. Patient records were reviewed for a minimum of one year following the initial injury.

Musculoskeletal injuries were classified according to the Muller AO classification system [7]. The presence of complications such as neurovascular injuries, compartment syndrome, and fracture-related infection and non-union was recorded. Nerve injuries were diagnosed through clinical examination by the treating clinicians, while arterial injury was diagnosed clinically and confirmed on computed tomography angiography (CTA) scans. Compartment syndrome was diagnosed by clinical examination and intra-operative findings.

The criteria proposed by Metsemakers et al. was used to describe fracture-related infection [8]. Confirmatory criteria included a fistula, sinus, or wound breakdown; purulent discharge from the wound or presence of pus during surgery; pathogens cultured from at least two deep tissue specimens; and presence of microorganisms taken from deep cultures [8, 9].

Non-union was defined as a lack of clinical or radiographic evidence of healing nine months after the injury and requiring a secondary procedure to obtain union [10, 11].

Cost analysis pertaining to the included parameters was performed using the hospital uniform patient fee schedule (UPFS) of a private patient and the 2014–2017 hospital implant tender document. The cost of blood products was calculated using data from the South African National Blood Service (SANBS), where one unit of packed red cells costs ZAR 1459 (USD 118), one unit of fresh frozen plasma costs ZAR 1288 (USD 104), and a unit of platelets cost ZAR 1796 (USD 145). The rand to dollar exchange rate was pegged at USD 1 to ZAR 12.4 (on 31/12/2017).

Data was captured in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analysed by using STATISTICA version 13.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Captured clinical and demographic data (Table 1) are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or means ± standard deviation for continuous variables, depending on the distribution, or as frequencies and counts for categorical data.

Results

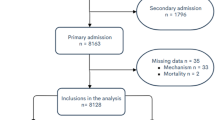

A total of 1800 patients with gunshot-related musculoskeletal injuries were identified during the study period. Of these, 351 patients were excluded due to incomplete documentation or having sustained injuries not requiring orthopaedic management. The burden of gunshot-related orthopaedic injuries showed similar rates between 2014 and 2016; however, an 11.1% increase from 2016 to 2017 was observed (Fig. 1).

The final cohort, which included mostly male patients (n = 1350, 93.2%), consisted of 1449 patients, with 1548 fractures, who sustained a total of 1706 musculoskeletal injuries. A total of 158 gunshot injuries included intra-articular gunshot injuries without an obvious fracture on the plain film radiographs (with no CT scan performed) and soft-tissue injuries with nerve fallout. The mean age was 28.2 ± 9.7 years, ranging from two to 71 years, with most patients (53%) being between 20 and 30 years of age and 56 patients (3.9%) being younger than 16 years old. A history of previous gunshot-related injury was observed in 27 (1.86%) patients. Of the included patients, 257 (17.7%) sustained more than one gunshot-related musculoskeletal injury.

Injuries included 1548 fractures and 158 soft-tissue injuries requiring orthopaedic review. These included intra-articular gunshot injuries without an obvious fracture on the plain film radiographs. The majority of fractures involved the lower limbs (n = 814, 52.6%), while 32.1% (n = 497) involved the upper limbs, 8.5% (n = 132) involved the pelvis, and 6.8% (n = 105) involved the spine (Fig. 2). The most common bone injured was the femur (n = 313, 20.6%), followed by the tibia (n = 273, 17.9%) (Fig. 2).

There were 263 (15.4%) intra-articular gunshot injuries involving the large joints. A total of 111 (6.5%) gunshot injuries involved the knee joint, 43 (2.5%) involved the elbow, 39 (2.3%) involved the hip, 30 (1.8%) involved the ankle, 23 (1.3%) involved the shoulder, and 17 (1%) involved the wrist.

There was a relatively equal split between gunshot injuries requiring surgery (n = 790, 46.3%) and injuries that could be treated non-operatively (n = 916, 53.7%). (Fig. 3) (Table 2) Treatment modalities included intramedullary nails (n = 329, 19.2%), plates and screws (n = 180, 10.6%), debridement/fasciotomy with or without bullet removal (n = 148, 8.7%), external fixation (n = 69, 4%), Kirschner wires (n = 56, 3%), and amputations as the first treatment in eight cases (0.5%). Temporary mono-lateral external fixation was employed in 23 patients (1.3%), while 46 patients (2.7%) had a circular external fixator as definitive fixation. Of the 23 patients who had temporary mono-lateral external fixators, nine were converted to hexapod circular fixators, five to intramedullary nails, and four to plate and screw fixation, while two patients underwent amputation and one was definitively managed in mono-lateral external fixation. Few surgical cases were performed with the sole indication being bullet removal. The only absolute indications our unit has for bullet removal are the bullet or fragments of it are lodged in a joint, the bullet causes impingement on a nerve or nerve root, the bullet is required for medico-legal examination, or lead poisoning is suspected. Our unit does not routinely test for lead serum levels. The total implant cost for operatively managed cases amounted to ZAR 8,257,133 (USD 665,898).

Patients who sustained gunshot-related orthopaedic injuries that required admission were admitted for a total of 9535 days, including 435 days in ICU, at a total cost of ZAR 24,434,380 (USD 1,970,515) (Table 3). The median duration of hospital stay was seven days (IQR 4.0–12.0 days) per patient with the longest admission being 99 days. Of those admitted to the ICU, the mean ICU duration of stay was five days (IQR 3.0–7.0 days).

A total of 14,589 imaging investigations were obtained, including 13,486 radiographs, 669 computerised tomography (CT) angiograms, 430 CT scans, and two magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, costing a total of ZAR 8,486,088 (USD 684,362). The most expensive imaging modality was CT angiograms at a total cost of ZAR 4,555,890 (USD 367,410) (Table 4). Blood products were administered to 149 patients (10.3%) including 526 units of packed red cells, 198 units of fresh frozen plasma, and 13 units of platelets. The cost of blood products totalled ZAR 1,045,806 (USD 84,339) (Table 4).

Emergency unit consultation fees amounted to ZAR 883,890 (USD 71,281) based on a cost of ZAR 610 (USD 49) per patient consultation (Table 5). Theatre costs were ZAR 10,551,240 (USD 850,906). This was calculated considering the 790 theatre episodes in this study, multiplied by the average three hours required per gunshot-related orthopaedic case as suggested by Martin et al. [6]. The total cost of care amounted to ZAR 53,658,537 (USD 4,320,043). The average cost per patient was ZAR 37,031 (USD 2986), with the most expensive patient costing ZAR 280,124 (USD 22,591) (Table 4).

Complications are summarised in Table 6. The most common complication was nerve injury (n = 128, 8.3%), followed by arterial injury (n = 101, 6.5%), fracture-related infection (n = 49, 3.2%), non-union (n = 48, 3.1%), and compartment syndrome (n = 25, 1.6%). Nerve and arterial injuries were more frequently observed following injuries involving the upper limb compared with the lower limb at rates of 4.8% versus 3.5% for nerve injuries and 4.6% versus 1.9% for arterial injuries respectively.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to quantify the overall burden of orthopaedic gunshot-related injuries at our institution over a four year period. Secondary aims included identifying complications from gunshot-related injuries and the additional burden it places on healthcare services.

This study highlights the enormous trauma burden of gunshot-related orthopaedic injuries at a level 1 trauma unit in South Africa. This is one of the largest single-centre studies on orthopaedic civilian gunshot injuries to date with only studies that considered multiple centres or those performed in war zones, exceeding the numbers reported in the present investigation [12,13,14,15,16,17]. This high trauma burden of gunshot-related orthopaedic injuries exacts a devastating cost on society and has an equally significant physical, emotional, and economic costs on its victims and their families. This is particularly evident in the Western Cape region, which has recently been plagued with an epidemic of gang violence to the extent that the South African National Defence Force has been deployed in the Cape Flats in an attempt to control the violence [18].

An unsettling finding is a high number of children and adolescents being among the victims (5%), with the youngest victim being only two years of age. The age and gender distributions were similar to publications by Martin et al. and Engelman et al., who also reported that young males made up the majority of cases [6, 19]. As reported in other similar studies, the lower extremity was more frequently injured but upper extremity gunshot injuries was associated with a higher rate of nerve and arterial damage [19]. The 8% rate of nerve injuries in our study was lower than those published by Walker et al. and Beidas et al., but the latter investigations included higher-velocity gunshot injuries and studies published in the military setting [17, 20].

Compartment syndrome was more frequently observed following lower extremity gunshot injuries, and, in our study, the most common complication was nerve injury. The fracture-related infection rate of 3.2% was comparable to closed fractures treated with operative intervention [20]. This was also comparable to Dougherty et al. [21] who found an infection rate of 1.5–5% for low-velocity gunshot injuries, and was significantly lower than the 15% wound infection rate reported by Abalo et al. [22] who predominantly treated lower limb fractures with internal fixation. We can postulate the following reasons for our relatively low fracture infection of 3.2%. Firstly, it is our trauma units’ protocol to administer antibiotics as soon as the patient arrives in our emergency unit. A first-generation cephalosporin is administered as soon as possible. Additional antibiotics are administered at the discretion of the orthopaedic resident who first reviews the patient. Secondly, our patient population is relatively young with a mean age of 28.2 ± 9.7 years, with the vast majority (91.6%) not having any medical co-morbidities. The vast majority of the gunshot injuries in our series were low velocity and extra-articular. There were only 4 patients in our entire series of 1449 patients who sustained high-velocity gunshot injuries, and only 263 (15.4%) gunshot injuries were intra-articular injuries of a large joint. It is also possible that we underestimated the rate of superficial wound infection. More than 30% of our patients did not follow up, and due to poor socio-economic conditions, it is likely that if they had a minor wound requiring attention, they would have presented to their primary care physician or clinic closest to their home and received a course of oral antibiotics.

More than half of the patients (53.7%) in the current series could be managed without surgical intervention. A possible explanation for this is that the vast majority of gunshot injuries in the series were low velocity and predominantly extra-articular. It is surprising to note the low percentage (4%) of patients requiring fracture stabilisation with external fixators, which can also be attributed to the fact that the majority of gunshot injuries were caused by hand guns and were therefore low velocity/low-energy injuries.

The burden of gunshot injuries at our institution is comparable to that seen in conflict areas with similar average number of gunshot-related injuries per year. During the Operation Iraqi Freedom, the Joint Theatre Trauma Registry recorded 2392 musculoskeletal gunshot injuries over a five year period between 2005 and 2009 [17]. The Al-Jala hospital in Libya treated 870 victims during a particularly bloody period of conflict of the 2011 civil war [15]. In comparison, at our institution, we treated 1706 musculoskeletal gunshot over a four year period from 2014 to 2017. Studies from England, Pakistan, and Nigeria have far fewer numbers of gunshot victims than seen in the current study [13, 14, 16] (Fig. 4).

There are several limitations for this study, as the data was collected retrospectively at a single institution and often had to rely on the availability of sufficient information recorded by the treating clinicians. From our review, more than 30% of gunshot victims in the study did not follow up after initial medical care; as a result, some of the complications might be under-reported. In addition, some complications relied on an intra-operative diagnosis and could be under-reported. Also, only direct costs were calculated, and fees for laboratory investigations, drugs, and other consumables were not included in the cost analysis.

The mental health and psychological burden of these injuries in patients and their families was not investigated and should be investigated in the future. The study does however have very large patient numbers, the data was collected over a four year period, and patient notes were accessed for at least a one year period after their injury to identify any late complications.

Conclusion

Our hospital is faced with an enormous burden of civilian gunshot-related orthopaedic injuries. This is comparable to studies published during the period of conflict and war. Although firearm violence has decreased in the early part of the decade due to the Firearms Control Act, there is a worryingly upward trend in gunshot violence in the Western Cape, South Africa, over the last few years. With improved understanding of this enormous burden, more healthcare resources can be allocated to this problem and better prevention strategies can be planned. Future studies evaluating the mental health and psychological burden experienced by gunshot victims as well as strategies to address societal issues that lead to interpersonal violence are warranted.

References

GBD Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390(10100):1211–1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2

The Global Burden of Disease (2016) Injury Collaborators. Global mortality from firearms, 1990-2016. J Am Med Assoc 320(8):792–814. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.10060

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2019) Global study on homicide 2019 Vienna 2019. https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/gsh/Booklet1.pdf. Accessed 4 Jan 2020

Gould C, Burger J, Newham G (2016) The SAPS crime statistics: what they tell us and what they don’t. S Afr Crime Q 42(6):3–11. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2012/v0i42a829

Thomson JDS (2016) A murderous legacy: coloured homicide trends in South Africa. S Afr Crime Q 44(7):9–14. https://doi.org/10.17159/24133108/2004/v0i7a1050

Martin C, Thiart G, McCollum G, Roche S, Maqungo S (2017) The burden of gunshot injuries on orthopaedic healthcare resources in South Africa. S Afr Med J 107(7):626–630. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i7.12257

Kellam JF, Meinberg EG, Agel J, Karam MD, Roberts CS (2018) Introduction: fracture and dislocation classification compendium: International Comprehensive Classification of Fractures and Dislocations Committee. J Orthop Trauma 32(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000001063

Metsemakers WJ, Kuehl R, Moriarty TF, Richards RG, Verhofstad MHJ, Borens O, Morgenstern M (2018) Infection after fracture fixation: current surgical and microbiological concepts. Injury 49(3):511–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2016.09.019

Dellinger EP, Miller SD, Wertz MJ, Grypma M, Droppert B, Anderson PA (1988) Risk of infection after open fracture of the arm or leg. Arch Surg 123(11):1320–1327. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400350034004

Nandra R, Grover L, Porter K (2016) Fracture non-union epidemiology and treatment. Trauma 18(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460408615591625

DiSilvio F, Foyil S, Schiffman B, Bernstein M, Summers H, Lack WD (2018) Long bone union accurately predicted by cortical bridging within 4 months. J Bone Joint Surg 3(4):3–12. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.18.00012

Held M, Engelmann E, Dunn R, Ahmad S, Laubscher M, Keel MJB, Hoppe S (2017) Gunshot induced injuries in orthopaedic trauma research. A bibliometric analysis of the most influential literature. Orthop Traumatol: Surg Res 103(1):801–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2017.05.002

Persad IJ, Srinivas Reddy R, Saunders MA, Patel J (2005) Gunshot injuries to the extremities: experience of a U.K. trauma centre. Injury 36(3):407–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2004.08.003

Yongu W, Onyemaechi N, Odatuwa-Omagbemi D, Elachi IC, Yongu WT, Nahachi C et al (2015) The pattern of civilian gunshot injuries at a university hospital in North Central Nigeria. J Dent Med Sci 14(2):87–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2004.08.003

Bodalal Z, Mansor S (2013) Gunshot injuries in Benghazi-Libya in 2011: the Libyan conflict and beyond. Surg: J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel 11(5):258–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2013.05.004

Niaz K, Shujah IA (2013) Civilian perspective of firearm injuries in Bahawalpur. J Pak Med Assoc 63(1):20–24

Walker JJ, Kelly JF, McCriskin BJ, Bader JO, Schoenfeld AJ (2012) Combat-related gunshot wounds in the United States military: 2000-2009 (cohort study). Int J Surg 10(3):140–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.01.005

Davis R (2019) Army deployed as gang violence escalates to unprecedented levels and residents cry out for help. The Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-07-12-army-deployed-as-gang-violence-escalates-to-unprecedented-levels-and-residents-cry-out-for-help. Accessed 26 Jan 2020

Engelmann E, Maqungo S, Laubscher Μ, Hoppe S, Roche S, Nicol A, Held M (2019) Epidemiology and injury severity of 294 extremity gunshot wounds in ten months: a report from the Cape Town trauma registry. S Afr Orthop J 18(2):31–36. https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2019/v18n2a3

Beidas OE, Rehman S (2011) Civilian gunshot extremity fractures with neurologic injury. Orthop Surg 3(2):102–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1757-7861.2011.00125

Dougherty PJ, Najibi S, Silverton C, Vaidya R (2009) Gunshot wounds: epidemiology, wound ballistics, and soft-tissue treatment. Instr Course Lect 58:131–139

Abalo A, Walla A, Ayouba G, Dellanh YY, Fortey K, Dossim A (2016) Internal fixation of gunshot induced fractures in civilians: anatomic and functional results of a standard protocol at an urban trauma center. Open J Orthop 6(3):63–70. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojo.2016.63010

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments and suggestions helped improve and clarify this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm that all authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following:

•The conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data.

•Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

•Final approval of the version to be submitted.

•Sound scientific research practice.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that this submission is in accordance with the principles laid down by the Responsible Research Publication Position Statements as developed at the 2nd World Conference on Research Integrity in Singapore, 2010.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained prior to commencement of data collection, with the approval number N17/10/106.

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Additional information

The authors further confirm that:

•The manuscript, including related data, figures, and tables, has not been previously published and is not under consideration elsewhere.

•No data have been fabricated or manipulated (including images) to support your conclusions.

•This submission does not represent a part of single study that has been split up into several parts to increase the quantity of submissions and submitted to various journals or to one journal over time (e.g. “salami-publishing”).

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jakoet, M.S., Burger, M., Van Heukelum, M. et al. The epidemiology and orthopaedic burden of civilian gunshot injuries over a four-year period at a level one trauma unit in Cape Town, South Africa. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 44, 1897–1904 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04723-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04723-6