Abstract

A total of 16 patients in our clinic (six women, ten men; mean age 54.87 years, range 38–78 years) were diagnosed as having a sacrococcygeal chordoma. Pain was the presenting symptom in all patients. In five patients, the chordoma was inoperable. A total of 11 patients were followed-up for a mean period of 64.8 months (range 7–152 months). Five patients were lost to follow-up (3 in the operable group and two in the inoperable group). The three remaining inoperable patients received radiation therapy. The eight remaining operable patients underwent a total of 12 operations (four anterior and posterior, eight posterior only). Five of these patients received adjuvant radiotherapy and two patients received both radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In follow-up, eight patients had evidence of disease and one patient remained disease-free. Problems encountered during therapy and follow-up included urinary incontinence (72%), rectal incontinence (36%), wound infection (36%), and lower extremity muscle weakness (36%). Two patients died from metastases to the lung. Of the remaining nine patients, eight were ambulatory, with seven needing support to walk. One patient was unable to walk at all due to lower extremity muscle weakness.

Résumé

Un total de 16 patients de notre clinique présentait un chordome saccrococcygien (6 femmes et 10 hommes d’age moyen 54,87 ans avec des extrèmes de 38 et 78 ans). La douleur était le symptôme dans tous les cas. Chez 5 patients la tumeur était inopérable. Onze patients avaient un suivi moyen de 64,8 mois (7–152). Cinq patients étaient perdus de vu (3 dans le groupe opérable et 2 dans l’autre). Les 3 autres patients inopérable recevaient de la radiothérapie. Huit patients étaient opérés avec un total de 12 opérations (8 uniquement postérieures et 4 antérieures et postérieures). Cinq d’entre eux recevaient une radiothérapie adjuvante et 2 une radio-chimiothérapie. Au recul, 8 patients sont en cours de maladie et 1 reste sans maladie. Les complications rencontrées étaient l’incontinence urinaire (72%), l’incontinence anale (36%), l’infection pariétale (36%), et l’insuffisance musculaire distale (36%). Deux patients décédaient de métastases pulmonaires. Des neufs patients restants, 8 sont ambulatoires, 7 ayant besoin d’un support pour marcher. Un patient est incapable de marcher à cause d’une faiblesse des membres inférieurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sacrococcygeal chordoma is a rare primary malignant tumour of the bone, and it is the most common primary sacral tumour [4, 7]. Chordomas are usually diagnosed late in the disease course and can become quite large. Management of chordomas has included surgical resection, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Despite these therapy modalities, recurrence is common [1, 14, 25].

The tumour rarely invades the rectal wall because the periosteum and presacral fascia are tough membranes that resist transgression by the tumour [15]. The proximity of the tumour to the rectum, neurovascular structures and organs such as the bladder make surgical excision difficult. Due to this difficulty, postoperative morbidity is high. Wide resection offers the best chance of cure and long-term disease-free control, but yields a substantially higher morbidity than subtotal intralesional resection.

Patients and methods

A total of 16 patients (six women, ten men; mean age 54.87 years, range 38–78 years) were diagnosed as having a sacrococcygeal chordoma in our Department of Orthopaedic Oncology from March 1986 to May 2005. In all patients with a chordoma, pain was the presenting symptom. Diagnosis was made via posterior fine-needle aspiration biopsy (four patients), Tru-cut needle biopsy (five patients) or open biopsy (seven patients). Five patients were diagnosed as having inoperable tumours, and two of these were lost to follow-up.

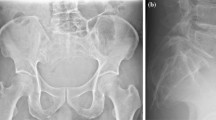

Before surgery, patients were evaluated neurologically, and this included tests of sphincter function and continence. At the time of tumour diagnosis, three patients had urinary incontinence, two had lower extremity paresthesia and three had lower extremity muscle weakness. In all patients, X-rays and computerised tomography (CT) were performed preoperatively. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed in 12 patients. Table 1 summarizes the patients’ characteristics.

For chordomas, surgical procedures are usually classified as wide resection, marginal excision or intralesional excision according to the following criteria. Wide resection involves en bloc excision of the tumour with the plane of resection passing through normal tissue (negative margins). Marginal excision involves removal of the tumour en bloc, with the plane of dissection passing through the pseudocapsule. Intralesional excision involves debulking, in which the tumour is removed piecemeal [7].

In the eight surgical patients who were followed up, a total of 12 operations was performed (four anterior and posterior, eight posterior only; nine marginal excisions, three intralesional excisions).

In the total of 11 patients who were followed up (eight operable, three inoperable), repeated evaluations included neurological examination as well as pelvic CT and MRI to check for tumour recurrence. Thoracic CT was also performed to check for lung metastases when this was considered necessary.

Results

A total of 11 patients were followed for a mean period of 64.8 months (range 7–152 months). The mean time interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis was 20.42 months (range 3–84 months).

Radiation therapy was administered in the three patients who were diagnosed as having inoperable tumours. In the eight patients who underwent surgical treatment, a total of 12 operations were performed: four anterior and posterior, eight posterior only, nine marginal excisions, and three intralesional excisions (Table 1).

Out of the eight surgical patients, five had neurological deficits postoperatively, with some patients having more than one deficit: bowel dysfunction (four patients), urinary incontinence (four patients), lower extremity muscle weakness (three patients) and wound infection (three patients). The infections were brought under control with debridement and the use of a first-generation cephalosporin. One of these patients (Patient 8) developed a soft tissue defect related to the infection, and this necessitated closure with a skin graft.

After the nine marginal excisions, local recurrence was encountered nine times (88.8%) within four to forty-five months of operation (Table 1). Metastatic lesions were encountered in five patients, two of whose metastatic disease was discovered when the inoperable chordoma was diagnosed. In the other three patients metastases developed at 12, 24, and 78 months after chordoma surgery. Of the five patients with metastatic disease, two died from complications due to lung metastases (Table 1).

In three patients the S1 nerve root was cut unilaterally during surgery; these patients developed bladder dysfunction and lower extremity muscle weakness, and one of them also had bowel dysfunction. In two patients, the S2 nerve roots were cut bilaterally, and these patients developed bladder and bowel dysfunction. In one patient the S2 nerve root was cut unilaterally, but by four months, urinary function had returned to normal (Patient 9).

Out of the total of 11 patients (operable or inoperable) who were followed up, eight patients experienced continuing disease, two patients died from metastases, and one patient was still disease-free nine months after surgery. In one patient, lower extremity weakness was progressive and this patient eventually became unable to walk. Of the patients who were able to walk, seven could walk with the use of a cane and one needed no assistance or equipment.

Discussion

Sacrococcygeal chordomas are malignant low-grade tumours, arising from remnants of the notochord [2, 13].

Because chordomas can develop insidiously, there can be a considerable time-lapse between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis. In our patients this interval was, on average, 22.34 months (range 3–84 months). This interval is longer than others reported in the literature [6, 14, 20].

The conventional radiographic findings in sacrococcygeal chordomas are the central location of the tumour, its destruction of several segments of the sacrum and its appearance as an anterior soft-tissue mass that occasionally contains small calcifications [15]. MRI is the best imaging method for evaluating the extension of the tumour into soft tissue.

The reported rates of metastasis occurrence with chordomas vary considerably in the literature, from 5% to 70% [2, 3, 10, 13, 15, 19, 25]. Of our 11 patients, four had lung metastases and another patient had metastases to both lung and left femur, which amounts to a metastasis rate of 45%.

For the surgical treatment of chordomas, methods include the combined abdominal and trans-sacral approach [11, 12] and the posterior approach [8, 22]. For proximal sacral lesions, the combined extended ilioinguinal and posterior approach is also useful [17]. The posterior approach is satisfactory for lesions at the third sacral segment or further caudal. Combined anterior and posterior exposure must be used for lesions that are located more cranially [9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 23].

The extent of surgical resection plays a major role in determining the length of the disease-free interval [14, 25]. Bergh et al. reported that in patients who received a wide surgical excision, the recurrence rate was 17%, while in patients who received intralesional or marginal resection the recurrence rate was 81% [3]. Yonemoto et al. emphasized that if gluteal invasion is present, the risk of recurrence is higher, and therefore a wide posterior surgical margin is important [24]. In our series, six out of eight surgically treated patients had gluteal invasion and the chordomas were large. A total of 12 operations were performed in eight patients (nine marginal, three intralesional). Of the nine marginal resections, eight were followed by local recurrence (88.8%).

The risk of postoperative neurological deficits is related to the number of sacrificed nerve roots [15]. The loss of the S4 and S5 nerves is not associated with any significant urinary or bowel problems [3]. All of these potential consequences must be discussed with patients before surgery. In our series, out of the five patients who had S1 and S2 nerve root damage, four had permanent sphincter dysfunction postoperatively.

Transrectal biopsy is not recommended in chordomas due to the risk of the rectal wall and presacral fascia becoming contaminated with tumour cells. If transrectal biopsy is performed, then the rectum must be resected during chordoma surgery [13]. All of our patients received posterior biopsies and the biopsy site was excised during surgery.

Radiotherapy after intralesional excision of chordomas has been reported as ineffective in some studies [5, 20], but other studies have reported that it can extend the time interval to recurrence [16, 25]. In one of our patients with inoperable chordoma, the patient’s complaints of pain and paresthesia resolved during the course of radiotherapy. Of the three patients who underwent intralesional excision, local control was achieved in two by means of radiotherapy. In our opinion adjuvant radiation therapy improves local control and pain, but does not improve the chances of cure in patients with subtotal resections.

Repeat operations are associated with higher morbidity than initial operations because of extensive scarring and difficulties in establishing tissue planes. For this reason, the widest possible surgical margins should be achieved in the first operation.

For long-term control of sacral chordomas, the superiority of wide resection over subtotal or even marginal intralesional resection is well known. For the patients in our series, wide resection was not possible because the tumours were very big, invading neighbouring tissues, and most patients wanted their sacral nerve roots to be retained; therefore, their disease could not be eradicated. Chordoma is a locally aggressive but slow-growing tumour, so early diagnosis and wide resection increase the chances of long-term control.

References

Arıel IM, Verdu C (1975) Chordoma: an analysis of twenty cases treated over a twenty-year span. J Surg Oncol 7:27–44

Azzarelli A, Quagliuolo V, Cerasoli S, Zucali R, Bignami P, Mazzaferro V, Dossena G, Gennari L (1988) Chordoma: natural history and treatment results in 33 cases. J Surg Oncol 37:185–191

Bergh P, Kindblom LG, Gutenberg B, Remotti F, Ryd W, Meis-Kindblom JM (2000) Prognostic factors in chordoma of the sacrum and mobile spine: a study of 39 patients. Cancer 88:2122–2134

Campanacci ML (1990) Bone and soft tissue tumors, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 639–651

Catton C, O’Sullivan B, Bell R, Laperriere N, Cummings B, Fornasier V, Wunder J (1996) Chordoma: long-term follow-up after radical photon irradiation. Radiother Oncol 41:67–72

Chandawarkar RY (1996) Sacrococcygeal chordoma: review of 50 consecutive patients. World J Surg 20:717–719

Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA (1980) A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop 153:106–120

Gennari L, Azzarelli A, Quagliuolo V (1987) A posterior approach for the excision of sacral chordoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br 69:565–568

Huth JF, Dawson EG, Eilber FR (1984) Abdominosacral resection for malignant tumors of the sacrum. Am J Surg 148:157–161

Huvos AG (1991) Bone tumors. Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. 2nd edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 599–624

Localio SA, Francis KC, Rossano PG (1967) Abdominosacral resection of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Ann Surg 166:394–402

Localio SA, Eng K, Ranson JH (1980) Abdominosacral approach for retrorectal tumors. Ann Surg 191:555–560

Mindell ER (1981) Chordoma. J Bone Surg Am 63:501–505

Rich TA, Schiller A, Suit HD, Mankin HJ (1985) Clinical and pathologic review of 48 cases of chordoma. Cancer 56:182–187

Samson IR, Springfield DS, Suit HD, Mankin HJ (1993) Operative treatment of sacrococcygeal chordoma. A review of twenty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 75:1476–1484

Saxton JP (1981) Chordoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 77:913–915

Simpson AH, Porter A, Davis A, Griffin A, McLeod RS, Bell RS (1995) Cephalad sacral resection with a combined extended ilioinguinal and posterior approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77:405–411

Stener B, Gutenberg B (1978) High amputation of the sacrum for extirpation of tumors. Principles and technique. Spine 3:351–366

Sundaresan N, Galicich JH, Chu FC, Huvos AG (1979) Spinal chordomas. J Neurosurg 50:312–319

Sundaresan N, Huvos AG, Krol G, Lane JM, Brennan M (1987) Surgical treatment of spinal chordomas. Arch Surg 122:1479–1482

Sung HW, Shu WP, Wang HM, Yuai SY, Tsai YB (1987) Surgical treatment of primary tumors of the sacrum. Clin Orthop 215:91–98

Waisman M, Kligman M, Roffman M (1997) Posterior approach for radical excision of sacral chordoma. Int Orthop 21:181–184

Wuisman P, Harle A, Matthiass HH, Roessner A, Erlemann R, Reiser M (1989) Two-stage therapy in the treatment of sacral tumors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 108:255–260

Yonemoto T, Tatezaki S, Takenouchi T, Ishii T, Satoh T, Moriya H (1999) The surgical management of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Cancer 85:878–883

York JE, Kaczaraj A, Abi-Said D, Fuller GN, Skibber JM, Janjan NA, Gokaslan ZL (1999) Sacral chordoma: 40-year experience at a major cancer center. Neurosurgery 44:74–79

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atalar, H., Selek, H., Yıldız, Y. et al. Management of sacrococcygeal chordomas. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 30, 514–518 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-006-0095-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-006-0095-x