Abstract

Between 1994 and 2001, a short-stemmed modular shoulder prosthesis was inserted in 62 shoulders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or osteoarthrosis (OA). We reviewed 53 patients with 60 shoulders (45 RA/15 OA) with at least 24 months follow-up. In 22 shoulders, we used a total shoulder prosthesis including a glenoid polyethylene component, whereas 38 shoulders only had a humeral component. In six shoulders, the humeral component was cemented. The average follow-up was 47 (24–99) months. There were no intraoperative complications but one wound infection and one patient with proximal migration of the humeral component. Hospital for Special Surgery Score increased from 44 (19–72) to 63 (21–93) points and Shoulder Function Assessment score (SFA) from 24 (12–46) to 42 (11–66) points. The VAS score for pain at rest improved from 4.3 to 1.9. Nonprogressive radiolucent lines were seen adjacent to nine glenoid and one humeral components. Fifty-six patients were satisfied with the result.

Résumé

Entre 1994 et 2001 une prothèse modulaire avec tige court a été insérée dans 62 épaules dans les malades avec polyarthrite rhumatoïde (RA) ou ostéoarthrose (OA). Nous avons examiné 53 malades avec 60 épaules (45 RA/15 OA) avec au moins 24 mois suivez. Dans 22 épaules nous avons utilisé une prothèse de l’épaule totale y compris un composant glenoid du polyéthylène, alors que 38 épaules avaient un composant humérale seulement. Dans six épaules le composant huméral a été cimenté. La suite moyenne était 47 (24–99) mois. Il n’y avait pas de complications intraopérative mais une infection de plaie et un patient avec migration proximal du composant huméral. Le Score de HSS augmenté de 44 (19–72) à 63 (21–93) points et score de SFA de 24 (12–46) à 42 (11–66) points. Les Score VAS améliorer de 4,3 à 1,9 en paix. Les lignes radiotransparent non-progressives ont été vues adjacent à neuf composants glénoïdes et un composant huméral. Cinquante-six malades ont été satisfaits avec le résultat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Excellent pain relief has been reported with a Neer-type shoulder prosthesis, whereas improvement in the range of motion (ROM) lags behind [1, 2, 15]. The position of the humeral head inside the rotator cuff plays an important role for the functional results [4, 5]. The introduction of a modular head has been an improvement, although by using a long stemmed design, position of the head depends still on the anatomy of the medullary canal. The long stem is also a problem in rheumatoid patients with ipsilateral shoulder and elbow replacements where increased stress has been reported in the humeral shaft between the implants [7, 8]. The Multiplex (ESKA Implants GmbH & Co, Lübeck, Germany), shoulder prosthesis was designed to avoid such problems (Fig. 1).

Material and methods

Between 1994 and 2001, the senior author (PMR) inserted 62 consecutive primary Multiplex shoulder prostheses. The surgical indications were pain and limitation of function associated with radiographic evidence of destruction of the glenohumeral joint. Indications for hemiarthroplasty were an intact glenoid with sufficient glenoid cartilage, severe destruction of the glenoid with insufficient bone stock and/or an irreparable massive rotator cuff tear.

Sixty shoulders [45 rheumatoid arthritis (RA)/15 osteoarthritis (OA)] in 53 patients with a minimum follow-up of 24 months were included in our analysis. Seven patients had bilateral shoulder prosthesis, and in nine cases, there was an ipsilateral elbow prosthesis. The mean follow-up was 47 (24–99) months. The average age of the patients was 66 years.

Patients were followed clinically 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery where a visual analogue scale (VAS), Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score and Shoulder Function Assessment (SFA) were completed and then every 1–2 years thereafter [17]. Radiographic assessment was performed on the first postoperative visit and then every 2 years thereafter. The assessment included measurement of humeral offset ratio (HOR: humeral geometric center with respect to the shaft of the humerus) [16] and examination for stress shielding [12] and loosening. The radiographs were also evaluated by an experienced radiologist [3]. Postoperative treatment consisted of passive exercises starting 2 days after surgery followed by active exercises.

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 11.01 (Chicago, IL, USA). The Student t-test, Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficient and univariate linear regression analyses were used; p<0.05 (two sided) was considered significant.

Results

Thirty-eight hemi- and 22 total shoulder arthroplasties (TSA) were inserted. Fifteen polyethylene and five metal-backed glenoid components were used (Biomet Inc, Warsaw, IN, USA and ESKA Implants). Six humeral components were cemented, the rest were bone ingrowth pressed-fit prostheses. One patient needed a muscle transfer (latissimus dorsi and teres major) to repair a massive rotator cuff tear.

Clinical evaluation

There were no intraoperative complications, but there were three postoperative complications all in rheumatoid patients with TSA. In one patient, a wound infection developed 2 weeks postoperatively. The patient recovered on antibiotics. In one patient, a proximal migration of the humerus made an acromioplasty necessary. One patient had a traumatic fracture of the greater tubercle and a rupture of the supra- and infraspinate muscles 3 months after surgery.

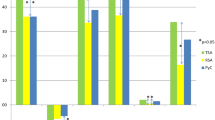

Postoperative results are presented at 2-year follow-up (Table 1). The HSS score increased from an average of 44 (19–72) to 63 (21–93) points (p<0.0001). The SFA improved from 24 (12–46) to 42 (11–66) points (p<0.0001). Results after 4 years (n=36) showed no significant differences in any of the outcome parameters. The VAS score for pain at rest improved from 4.3 to 1.9 (p<0.0001) and for pain during daily activities from 7.8 to 3.6 (p<0.001). Three patients showed no improvement and two patients were worse.

Active forward flexion increased from an average of 64° (0–120°) to 98° (20–160°) (p<0.0001). Active abduction increased from an average of 53° (0–90°) to 88° (20–150°). Active external rotation improved from 10°(−40–90°) to 25°(−30–70°) (p<0.0001). Internal rotation as measured on the vertebral column also increased significantly (p=0.005), improving from the sacrum to the lumbar spine. Postoperative external rotation increased significantly, more so in rheumatoid patients with hemiarthroplasties compared to TSA (p=0.03).

Analysis of covariates showed that the postoperative ROM was significantly related to several parameters such as pain at rest and during activities, rotator cuff status, preoperative ROM, and postoperative external rotation (Table 1). The influence of these parameters together and apart was analyzed using a multiple regression analysis in a linear model. There was no confluent relation between the parameters.

In rheumatoid patients with a TSA the postoperative AFF increased with ß=1.0 and ß=0.92 per unit for the preoperative flexion and postoperative external rotation respectively (p<0.001). For hemiarthroplasty in RA patients the biggest influence on the AFF was found in the amount of pain during activities and postoperative external rotation (ß=8.4 and ß=0.64; p<0.001)

Seven daily living activities were scored from 0 to 5 (0 not being able at all and 5 normal function). The percentage of patients being able to do the following daily living activities, without severe difficulties or help, significantly increased after surgery: dressing, wash opposite axilla, combing hair, perineal care, and sleeping on the affected side (p<0.001). Reaching behind the back and lifting weight was not significantly improved.

The status of the rotator cuff was peroperatively evaluated. The presence of a cuff tear negatively influenced the postoperative results.

Radiographic evaluation

The average HOR for the different diagnoses did not exceed the standard error of measurement given by Rozing and Oberman [16] (0.69±0.06). In 12 shoulders, the geometric center of the humeral head was located more laterally with respect to the humeral shaft axis. In ten shoulders, there was a more medial position, and in 38 shoulders, the geometric center was located within two SD of the mean normal anatomic HOR (Table 2, Fig. 2)

Lucent lines as seen on anterior-posterior radiographs were present in nine glenoid components and in one humeral component (all cemented). None were complete or exceeded 2 mm, none were progressive, and none were shifted, therefore none were considered loose by either of the three observers. No radiolucent lines or signs of stress shielding were found near humeral stems or around the metal-backed glenoid components (Table 2).

Fifty-six patients were satisfied with the result and four were not and would not choose this operation again.

Discussion

The outcome after shoulder joint replacement is reported equally successfully independent of the various component designs [1, 2, 5, 10]. Theoretical and actual disadvantages have frequently been discussed [5, 6, 9]. Our report on the Multiplex short-stemmed total shoulder system also presents good results with improvement of ROM, function and pain relief as compared to other designs [15]. Levy and Copeland’s series on surface replacement arthroplasty showed similar successful results, though the glenoid component replacement proved to be difficult and loosening of the cup, especially in the severely deformed rheumatoid humeral head, was of concern [11]. With the Multiplex shoulder prosthesis, the humeral head is removed, but the humeral metaphysis and shaft remain largely intact. Because of this, the prosthesis can be used in rheumatoid shoulders with severe destruction and offers the possibility for glenoid replacement.

In our series of rheumatoid patients, we found a substantial difference in the improvement of external rotation as well as active forward flexion between hemi- and total arthroplasties. We also found a significant correlation between the ability to externally rotate and the postoperative improvement of active forward flexion. To our knowledge, this relation has never been analyzed. The loss of external rotation has been blamed on “overstuffing” the glenohumeral capsule when a glenoid component is inserted [14]. In our series, we found that postoperative ROM was largely determined by preoperative ROM, and the preoperative ROM matched the status of the rotator cuff. We therefore believe that timing of shoulder joint replacement is essential and might improve the postoperative functional outcome.

The position of the humeral head center as measured in medial-lateral direction had very little influence on the postoperative ROM in rheumatoid patients when we corrected for the various parameters that would also influence the postoperative result. This might be due to a great variation in postoperative ROM but could also imply that preoperative ROM, postoperative pain, and external rotation had a greater influence on postoperative ROM than humeral offset, as measured in the scapular plane [4, 13].

The theoretical disadvantages of the short-stemmed humeral component design and its modular head were not encountered. The short stem did not present a higher risk for humeral loosening, as we found no signs of loosening or stress shielding. We saw no component-related complications, and none of the humeral components were revised. Nor did we did see any complications (e.g., fractures) related to stress rising in between the humeral stems [7] in patients with ipsilateral elbow and shoulder prosthesis.

Although most patients have not yet reached a 5-year follow-up period and long term follow-up results are awaited, we have not seen any signs of loosening, stress shielding, or a relevant change in function, pain and ROM in patients with a follow-up of more than 5 years (n=17). Over time, postoperative results have stayed relatively stable. We therefore believe the Multiplex short-stem shoulder prosthesis to be a good alternative for the conventional shoulder prosthesis, especially in rheumatoid patients.

References

Bell SN, Gschwend N (1986) Clinical experience with total arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty of the shoulder using the Neer prosthesis. Int Orthop 10:217–222

Boss AP, Hintermann B (1999) Primary endoprosthesis in comminuted humeral head fractures in patients over 60 years of age. Int Orthop 23:172–174

Brenner BC, Ferlic DC, Clayton ML, Dennis DA (1989) Survivorship of unconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 71:1289–1296

de Leest O, Rozing PM, Rozendaal LA, van der Helm FC (1996) Influence of glenohumeral prosthesis geometry and placement on shoulder muscle forces. Clin Orthop 330: 222–233

Fenlin JM Jr, Ramsey ML, Allardyce TJ, Frieman BG (1994) Modular total shoulder replacement. Design rationale, indications, and results. Clin Orthop 307: 37–46

Gartsman GM, Russell JA, Gaenslen E (1997) Modular shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 6:333–339

Gill DR, Cofield RH, Morrey BF (1999) Ipsilateral total shoulder and elbow arthroplasties in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 81:1128–1137

Inglis AE, Inglis AE Jr (2000) Ipsilateral total shoulder arthroplasty and total elbow replacement arthroplasty: a caveat. J Arthroplasty 15:123–125

Kelly II JD, Norris TR (2003) Decision making in glenohumeral arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 18:75–82

Kelly IG (1994) Unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop 307: 94–102

Levy O, Copeland SA (2001) Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty of the shoulder. 5- to 10-year results with the Copeland mark-2 prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 83:213–221

Nagels J, Stokdijk M, Rozing P (2003) Stress shielding and bone resorbtion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 12:35–39

Orfaly RM, Rockwood CA, Jr., Esenyel CM, Wirth MA (2003) A prospective functional outcome shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis with an intact rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 12:3–214

Pearl ML, Kurutz S (1999) Geometric analysis of commonly used prosthetic systems for proximal humeral replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 81:660–671

Rodosky MW, Bigliani LU (1996) Indications for glenoid resurfacing in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 5:231–248

Rozing PM, Obermann WR (1999) Osteometry of the glenohumeral joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 8:438–442

van Den Ende CH, Rozing PM, Dijkmans BA, Verhoef JA, Voogt-van der Harst EM, Hazes JM (1996) Assessment of shoulder function in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 23:2043–2048

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Statement on conflict of interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van de Sande, M.A.J., Rozing, P.M. Modular total shoulder system with short stem. A prospective clinical and radiological analysis. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 28, 115–118 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-004-0537-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-004-0537-2