Abstract

Tumors and their surrounding area represent spatially organized “ecosystems”, where tumor cells and the immune contextures of the different compartments are in a dynamic interplay, with potential clinical impact. Here, we aimed to investigate the prognostic significance of peritumoral tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) either alone or jointly with the intratumoral densities and spatial distribution of CD8 + and CD163 + cells in breast cancer (BCa) patients. TLS were identified peritumorally, within the area distancing up to 5 mm from the infiltrative tumor border, counted and further characterized as adjacent or distal, in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue samples from a cohort of 167 patients, with histologically confirmed invasive ductal BCa. TLS and tumor-infiltrating immune cells were determined by H&E and immunohistochemistry. Clinical follow-up was available for 112 of these patients. Patients with peritumoral TLS exhibited worse disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) as compared to patients lacking TLS. Moreover, the density of peritumoral TLS was found to be crucial for prognosis, since patients with abundant TLS exhibited the worst DFS and OS. By combining the density of adjacent TLS (aTLS) with our recently published intratumoral signatures based on the differential distribution of CD8 + and CD163 + in the tumor center and invasive margin, we created two improved immune signatures with superior prognostic strength and higher patient population coverage. Our observations strengthen the notion for the fundamental role of the dynamic interplay between the immune cells within the tumor microenvironment (center/invasive margin) and the tumor surrounding area (peritumoral TLS) on the clinical outcome of BCa patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the last decades, cancer immunotherapy has evolved from a promising therapeutic modality to a robust clinical reality [1], switching from the traditional cell-centric cancer treatments to new holistic therapeutic approaches which consider both, the tumor microenvironment and immune contexture [2]. Studies from immunotherapy trials, using immune checkpoint inhibitors [3], have demonstrated profound clinical benefit in a proportion of patients with varied tumor types, although most patients do not respond to such therapies, highlighting the need for developing biomarkers to guide proper selection of patients. Given the established significance of patients’ immune profile regarding tumor initiation, development, and response to therapies, many studies have investigated the impact of the complexity and diversity of the tumor microenvironment on clinical outcome [4, 5].

Tumor immune cell infiltration is progressively becoming an important aspect for clinical outcome prediction of cancer patients. Particularly, in colorectal cancer, the “Immunoscore”, comprising an immune cell infiltration signature considering densities and location of CD3 + and CD8 + cells, has been proposed to be more informative than the standard AJCC/TNM staging [6]. In breast cancer, although a high degree of immune infiltration has been repeatedly reported to associate with survival benefit [7], the establishment of validated prognostic immune signatures in the distinct tumor compartments remains elusive. In our recent study, we have highlighted the importance of the differential spatial (tumor center; TC and invasive margin; IM) distributions of TIL subpopulations (CD8 + and CD163 +), single or jointly analyzed, on clinical outcomes in breast cancer patients [8].

Besides the differential immune infiltrates in TC and IM, there is a “third level biomarker” that orchestrates the tumor immune microenvironment, namely the tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) which can be found as intratumoral and peritumoral clusters of immune cells. TLS are lymph node-like structures that develop inside non-lymphoid organs, architecturally and functionally similar to secondary lymphoid organs (SLO) [9]. They are ovoid, mainly lymphocytic, aggregates that contain centrally an ill-defined B cell-rich area that may include a well-defined germinal center and a subtle network of follicular dendritic cells. This area is surrounded by a parafollicular T cell-rich area with extravasation of lymphocytes into the tissue. Sometimes, these lymphoid aggregates are not arranged in distinct B and T cell areas, indicating probably different stages of TLS maturation [10, 11]. TLS presence has been noted as a response in cases of chronic inflammation due to persistent antigen stimulation (e.g., GVHD, Crohn’s disease) [12], autoimmune conditions (like lymphocytic thyroiditis and rheumatoid arthritis), and several solid tumors [13,14,15].

To date, the presence of TLS in the tumor microenvironment has been mainly correlated with favorable clinical outcomes in various malignancies [9, 16,17,18,19] also including BCa [20,21,22,23]. Moreover, there are reports investigating the prognostic relevance of TLS in particular breast cancer subtypes (TNBC or HER-2/neu ±), jointly with total TILs, but not with TILs distributed in the different breast tumor areas [23, 24]. Other studies in BCa have reported a correlation of TLS with higher tumor grade [24, 25], while in murine lung models TLS have been found to contain significant numbers of Tregs, thus acting as immunosuppressors, decreasing the effectiveness of therapy [26]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, TLS located in liver parenchyma have been proposed to act as microniches for tumor progenitor cells, promoting cancer cell stemness [27]. However, the role of TLS in this case is blurred due to a possible different function of outlier TLS from the tumor core.

Based on this potential functional pluralism of TLS, we suggest that their further characterization (e.g., spatially, compositionally, and functionally) in the tumor and the surrounding area will shed more light on the adaptive tumor-reactive immune mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment. We have previously demonstrated the importance of immune infiltration in breast cancer based on the combined differential densities of CD8 + and CD163 + cells in the TC and IM, resulting in the identification of favorable and unfavorable combined immune signatures (FCIS and UCIS, respectively) with significant prognostic value [8]. Nevertheless, there were a considerable number of patients, about 50% of the total cohort analyzed, who could not be classified either in the favorable or the unfavorable prognosis group. Consequently, it would be essential to find an additional discriminating and sensitive factor in the tumor microenvironment to guide classification of these patients into prognostic groups. Another interesting finding from our study was that patients with accumulation of CD8 + cells in the IM exhibited poor prognosis in contrast with colon cancer patients [28], emphasizing the key role for the spatial distribution of the immune cells in different tumor types for patients’ survival. From this perspective, it is obvious that the immune contexture in the different tumor’s compartments (e.g., TC, IM, TLS) is crucial for the orchestration of the antitumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment.

As outlined above, studies in breast cancer have been mainly focused on TLS intratumorally [22,23,24], thus neglecting to a great extent their prognostic significance when these are located peritumorally (i.e., outside of, but adjacent to the IM). In the present study, we aimed to investigate the prognostic significance of peritumoral immune cells organized into TLS, either alone or jointly with differential intratumoral densities of immune infiltrates in TC/IM. This approach strongly supports the concept that the combined analysis of the presence, quantity, and immune contexture of peritumoral TLS, together with the differential distribution of intratumoral CD8 + and CD163 + cells in the TC and IM, may provide significant information on the immune status of the tumor microenvironment, possibly leading to an improved powerful reinforced biosignature for clinical outcomes of breast cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

A total of 167 tumor samples (47 from the prospective arm and 120 from the retrospective arm of our previous study [8]) were selected from women with histologically confirmed invasive ductal breast cancer diagnosed at Saint Savas Cancer Hospital during a 15-year period (2000–2015). CD8 + and CD163 + cells were quantified in TC and IM immunohistochemically in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue samples from our recent study [8]. As breast cancer is a very heterogeneous disease, we tried to limit this heterogeneity by including in our study cohort only patients with invasive ductal carcinoma, without any distal metastasis, muscle or skin involvement, bilateral cancer, or history of any other malignancy. Cases with preoperative neoadjuvant therapy were excluded.

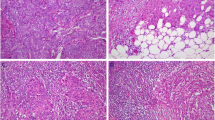

Paraffin block selection and immunohistochemistry

Multiple serial 3–4 μ sections were obtained from blocks of FFPE tissues and their respective hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) slides were reviewed by two experienced pathologists who selected areas from each tumor containing a substantial amount of tumor-infiltrative margin (minimum length of 28 mm-average 45 mm) surrounded by at least 5 mm of peritumoral breast parenchyma. These were stained with antibodies specific for CD4 (4B12, 1:40, Biogenex), CD8 (SP16, 1:80, Thermo Scientific), CD163 (10D6, 1:400, Biocare), and FOXP3 (236A/E7, 1:100, Abcam) for quantifying immune infiltrates in TLS. In some cases, the slides were also stained with anti-CD20 (L26, 1:500, Dako), anti-CD3 (LN10, 1:200, Novocastra), anti-CD23 (DAK-CD23, 1:80, Dako), and anti-CD31 (JC70A, 1:70, Dako) to validate the presence of TLS by demonstrating their content of B cells, T cells, and dendritic cells and high endothelial venules (HEVs), respectively (Suppl Fig. 1). Staining with CK7 (OV-TL 12/30, 1:200, Dako) was also performed for verifying the presence of cancer cell clusters inside TLS. Immunostaining was carried out using the Leica Bond III automation system (Leica Biosystems, Melbourne, Australia) and the Leica detection kit (Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK). Immunohistochemical staining was optimized using hyperplastic tonsil tissue.

TLS quantification and grouping

The presence and location of peritumoral TLS in each tumor was assessed in serial slides (both H&E and immunohistochemically stained) and only those distancing up to 5 mm from the infiltrative tumor border, including those associated with ductal in situ (DCIS) component, were scored [24, 29]. On H&E stained slides, TLS were identified morphologically as distinct ovoid lymphocytic aggregates presenting high endothelial venules (HEV) and/or a germinal center. As the use H&E alone has been proven to underestimate the presence of TLS [30], the utilization of immunohistochemical staining for CD4, CD8, and FoxP3 was used as a subsidiary means of detection. In equivocal cases, their identification was validated with supplementary immunostaining for CD31, CD20, CD3, and CD23. At least five serial slides per tumor (1 H&E and 4 immunostains) were evaluated and the mean number of TLS was recorded.

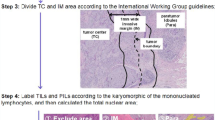

TLS were grouped in adjacent (aTLS) and distal (dTLS), according to distance and interposition of normal breast tissue (that is lobules, ducts, or adipose tissue without inflammation or desmoplastic stroma) between them and the infiltrative tumor margins [31]. Infiltrative tumor margins were defined as the outermost edge of invasive carcinoma disregarding any peripheral fibroinflammatory or desmoplastic response. aTLS were considered as those situated tangentially to the tumor-infiltrative border surface or bridged to it by non-normal breast tissue. dTLS were considered as those TLS that have normal breast tissue inter-positioned between them and the tumor-infiltrating border (Fig. 1a). The presence and number of aTLS and dTLS was evaluated on each slide. Tumors were then subgrouped in three arbitrary categories based on the number of aTLS: negative, low to moderate (1–4 aTLS), and high (≥ 5 aTLS). Implementation of serial FFPE sections allowed the assessment of CD4, CD8, FOXP3, and CD163 cells in each TLS separately in 118 out of the 167 patients (39 patients of the prospective cohort and 79 patients retrospectively analyzed, from our previous study), for whom staining for all four markers was available. The immunohistochemical evaluation revealed variations in CD4 +, CD8 +, FOXP3 + and CD163 + cell densities, which allowed their categorization in four density groups: very low, low, medium, and high with percentages of positive cells scored in each group, 0–10, 10–20, 20–30, and > 30, respectively (Fig. 5e). We determined a mean infiltration in aTLS and dTLS, due to the high degree of uniformity of infiltrating patterns of CD4 +, CD8 +, FOXP3 +, and CD163 + cells detected in every single patient.

Adjacent and distal TLS and their relation to clinicopathological characteristics. a Two aTLS and one dTLS, stained with anti-CD3 (× 40 magnification), are shown. The invasive margin (IM) of the tumor is also visible. b Shown is an aTLS next to the tumor with a cluster of cancer cells (cytokeratin staining, × 100 magnification). c Distribution of aTLS and dTLS-positive or -negative tumors among BCa patients stratified by molecular subtypes. Percentages of d aTLS and e dTLS-positive (+) or -negative (−) tumors in the total BCa patient population and in groups of patients stratified by clinicopathological characteristics. f Presence of aTLS within dTLS − (dTLS0) and dTLS + patients. (p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**, p ≤ 0.0001****)

Statistical analysis

Contingency and survival plots were created using Prism GraphPad 7.01. All the contingency statistical tests (Chi square, Fisher’s exact test) were carried out using the number of patients and not their percentages, although the corresponding graphs present percentages. Thus, p values refer to the real number of patients evaluated in each case. The non-parametric (Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis) tests were used to analyze continuous variables. In the survival analyses, both, log-rank p and Gehan–Breslow p were considered. p values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses (Cox regression) were conducted in IBM SPSS 24. For the multivariate analysis, the forward stepwise method was used using the threshold of 0.05 as an entry point.

Results

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of adjacent and distal TLS and their relation to clinicopathological characteristics and clinical outcome

The clinicopathological characteristics of the 167 breast cancer patients evaluated in the present study are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The number of peritumoral aTLS and dTLS (Fig. 1a) was determined and their relation to the patient clinicopathological characteristics was investigated (Fig. 1d, e). Notably, some aTLS and dTLS were found to contain clusters of cancer cells (Fig. 1b). aTLS were detected in the majority of patients (Fig. 1d). Higher numbers of patients lacking aTLS were detected among those with better prognosis based on clinicopathological characteristics, i.e., lower TNM stage, well-differentiated tumor cells (G1, 2), absence of infiltrated lymph nodes (N0), and smaller tumors (T ≤ 2 cm), although statistically significant differences were detected only for tumor grade (Fig. 1d). On the other hand, dTLS were present in the minority of our patients (Fig. 1e). Among those, grade 3 patients had statistically higher dTLS vs patients with grades 1 and 2 (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, all patients with HER2 + molecular subtypes (Luminal B/HER2 + and HER2 +) had aTLS, while dTLS were more often detected in patients having molecular subtypes without hormone receptors (either HER2 + or TNBC; Fig. 1c).

The presence of aTLS relative to dTLS number was also investigated. Figure 1f clearly shows that the vast majority (approximately 95%) of dTLS + tumors also harbors a higher number of aTLS (≥ 5), the rest were scored with aTLS (1–4) and none lacked aTLS. The latter was confirmed by our findings showing that patients with no aTLS (i.e., aTLS0) also lacked dTLS (i.e., were dTLS0) (Fig. 1f, left column).

In a group of 112 patients with clinical follow-up data (clinicopathological and treatment characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 2), we examined the association of peritumoral TLS with DFS and OS. Patients with aTLS exhibited significantly lower DFS than those without aTLS; OS was also lower in patients with aTLS, although statistical significance was not reached (Fig. 2a). In an analogous manner, patients with dTLS had statistically significantly worse DFS and OS than those lacking dTLS (Fig. 2b).

Adjacent and distal TLS and their relation to clinical outcome. Clinical outcome (Kaplan–Meier disease-specific survival curves) in patients with a aTLS − and aTLS + tumors or b dTLS − and dTLS + tumors. c Clinical outcome in patients with TLS-negative tumors (aTLS − dTLS −), or with tumors harboring only aTLS (aTLS + dTLS −) or both aTLS and dTLS aTLS (aTLS + dTLS +). d Statistical analyses among the indicated groups

Moreover, the combined presence of both, aTLS and dTLS (aTLS + dTLS +), defined a group of patients with the worse clinical outcome, in terms of both DFS and OS (Fig. 2c). Patients having aTLS + dTLS − tumors exhibited a lower risk for recurrence and death than double-positive patients (i.e., aTLS + dTLS +). As expected, patients lacking both aTLS and dTLS (i.e., aTLS − dTLS −) had the best clinical outcomes (Fig. 2c). All statistical considerations among these groups, with significant differences in bold, are shown in Fig. 2d.

We next determined DFS and OS in our patients stratified by the number of aTLS. Interestingly, we observed that in the aTLS + tumors, the number of aTLS (i.e., aTLS1–4 vs aTLS ≥ 5) did not substantially impact their DFS, whereas both groups exhibited statistically lower DFS vs patients whose tumors lacked aTLS (Fig. 3a). In contrast to what we observed when comparing for DFS, the OS was statistically significantly lower in the group of patients with aTLS ≥ 5 vs those with aTLS –4 tumors. This latter group of patients had indistinguishable OS with patients lacking aTLS (Fig. 3a, b). These data confirm that lack of aTLS represents a favorable prognosticator and also suggests that the number of aTLS in the aTLS + tumors differentially affects DFS and OS. Figure 3c shows the distribution of the three groups among the molecular subtypes, with HER2 + patients lacking aTLS, as also shown above (Fig. 1c). As also expected, the frequency of patients with high numbers of aTLS was significantly increased among groups with unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics (i.e., increased tumor size, grade, and stage) (Fig. 3d).

Number of aTLS and their relation to clinicopathological characteristics and clinical outcome of patients. a Clinical outcome in patients with tumors without aTLS (aTLS0) or with up to 4 aTLS (aTLS1–4) and ≥ 5 aTLS (aTLS ≥ 5). b Statistical analyses among groups. c Distribution of aTLS-negative (aTLS0) or aTLS-positive (aTLS1–4 and aTLS ≥ 5) tumors among BCa patients stratified by molecular subtypes. d Distribution of aTLS-negative (aTLS0) or aTLS-positive (aTLS1–4 and aTLS ≥ 5) tumors among BCa patients stratified by clinicopathological characteristics. (p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**)

Intratumoral immune infiltration and peritumoral TLS: an advanced level of the tumor immune profile

We have previously demonstrated the prognostic value of intratumoral CD8 + and CD163 + immune cells differentially distributed in TC and IM in breast cancer patients by establishing one favorable combined immune signature (FCIS) consisting of high CD8 + cell densities in the TC and low (L) ones in the IM (CD8HL) combined with opposite densities of CD163 + cells in the same regions (i.e., CD163LH). Inversely, CD8LH along with CD163HL comprised an unfavorable signature (UCIS) [8]. Nonetheless, by grouping our patients in either of these two signatures, we were left with a considerable number of patients (close to 50%; REST group), with distinct patterns of immune infiltration in their primary tumors which could not lead to conclusive prognosis of either DFS or OS. This group contained patients whose CD8 + and CD163 + cells were homogenously distributed in TC and IM comprising four subgroups, namely CD8LL/CD163LL, CD8HH/CD163HH, CD8HH/CD163LL, and CD8LL/CD163HH [8]. By examining aTLS and dTLS distribution within the FCIS, UCIS and REST groups, we observed that in the UCIS group the vast majority of patients had aTLS ≥ 5 (24 of 29; 83%), compared to patients having the FCIS (21 of 38; 55%) or REST (41 of 73; 56%) signatures (FCIS vs UCIS p = 0.0403 and REST vs UCIS p = 0.0384) (Fig. 4a). Moreover, a higher percentage of patients in the UCIS group presented with dTLS as compared to the two other groups, although not reaching statistical significance (Fig. 4b). Intra-analyses in the REST group revealed major differences with respect to the aTLS patterns among the four subgroups: the LL/LL group exhibited the best aTLS profile having the highest frequency of patients (33%) with the favorable aTLS0 and only 17% of patients having unfavorable aTLS ≥ 5 with statistically significant differences compared to the other three subgroups which scored high aTLS ≥ 5 and low aTLS0 profiles (60–81% and 0–10%, respectively; Fig. 4c). With regard to aTLS distribution, in an analogous manner with the total patient population, also in the REST group we found aTLS0 tumors to be associated with improved DFS and OS as compared to those being positive for aTLS (i.e., aTLS1–4 and aTLS ≥ 5; Fig. 4d–f).

aTLS and dTLS distribution in the FCIS, UCIS, and REST patients groups. a Percentages of patients in the FCIS, REST, and UCIS groups with aTLS-negative (aTLS0) or aTLS-positive (aTLS1–4 and aTLS ≥ 5) tumors and b with dTLS-negative (dTLS0) or dTLS-positive (dTLS +) tumors. c Subgroups in the REST group with aTLS-negative (aTLS0) or aTLS-positive (aTLS1–4 and aTLS ≥ 5) tumors stratified by immune infiltrates in the TC and IM; LL/LL: low number of CD8 + in the TC and IM and low number of CD163 + in the TC and IM; HH/LL: high number of CD8 + in the TC and IM and low number of CD163 + in the TC and IM; HH/HH: high number of CD8 + in the TC and IM and high number of CD163 + in the TC and IM; LL/HH: low number of CD8 + in the TC and IM and high number of CD163 + in the TC and IM. d, e Clinical outcome in patients belonging to the REST group with tumors having aTLS0, aTLS1–4, or TLS ≥ 5. f Statistical analyses among groups

The reinforced immune signatures: a comprehensive “third level” assessment of tumor microenvironment immune profile

In an attempt to improve our recently described combined signatures (FCIS and UCIS) [8] so as to increase their prognostic value and also to cover a broader patient population, we reevaluated them by additionally considering aTLS patterns, thereby defining two new signatures which were called “Reinforced” Favorable or Unfavorable Combined Immune Signatures and were designated as RFCIS and RUCIS. Since the number of patients with aTLS0 in the “REST” group was very small to be separately evaluated (only 8 patients with clinical follow-up; see Fig. 4d, e) and the clinical outcomes between the two groups, aTLS0 and aTLS1–4, did not differ significantly (Fig. 4f), we further proceeded with our analyses by combining aTLS0 and aTLS1–4 in one group. Thus, patients belonging to the RFCIS group were either CD8 HL and/or CD163 LH (i.e., FCIS), and/or aTLS0–4. All the remaining patients were classified within the RUCIS group: CD8 LH and/or CD163 HL (i.e., UCIS) and/or aTLS ≥ 5 (see also Suppl. Figure 2). Figure 5a shows how combining the FCIS with aTLS adds to the prognostic impact. The RFCIS group had a significantly better clinical outcome than the RUCIS, in terms of both DFS and OS, which was robustly pronounced as compared to analogous comparisons between FCIS vs UCIS [8] and aTLS0/aTLS1–4 vs aTLS ≥ 5 (see Fig. 3a, b). The 5-year probability for DFS was 93% for the RFCIS patients vs 61% for the RUCIS. Accordingly, the 5-year probability for OS was 96% vs 77% (Fig. 5b). Kaplan–Meier curves illustrating survival of patients stratified by their tumor molecular subtype can be seen in Suppl. Figure 3A. Interestingly, we observed that patients with the RFCIS signature, irrespective of the tumor molecular subtype, had better clinical outcomes than those with the RUCIS signature. There was a trend for higher frequency of RUCIS vs RFCIS among the groups with unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics, reaching statistical significance in the groups for early vs advanced stage, grade 1, 2 vs grade 3, and HER2 − vs HER2 + (Fig. 5c). An increased frequency of RUCIS patients was also observed among the HER2 + molecular subtypes, i.e., luminal B/HER2 + and HER2 + subgroups (Fig. 5d). Moreover, no significant differences in the cell infiltration of TLS by CD4 +, CD8 +, or CD163 + could be detected among the two groups (Fig. 5e). On the contrary, TLS infiltrated with FOXP3 + lymphocytes were significantly increased in the RUCIS patient group (Fig. 5e).

The reinforced immune signatures. a Clinical outcome in BCa patients with RFCIS or RUCIS reinforced signatures. b %Probability and number of subjects at risk at 5 years for DFS and OS. c Distribution of the reinforced immune signatures in the total patient population and in patients’ groups based on clinicopathological parameters. d Distribution of the reinforced signatures among BCa patients with different molecular subtypes. e Densities of CD4, CD8, CD163, and FoxP3 cells within TLS in BCa patients having RFCIS or RUCIS. Statistical significance refers to comparison of the percentage of patients. (p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**)

To investigate the prognostic significance of the new reinforced combined immune signatures, we conducted univariate and multivariate analysis (Table 1). In the univariate analysis for molecular subtype, early vs advanced stage (i.e., AJCC stages 1 and 2A vs 2B and 3), T status, N status, grade, expression of hormone receptors and HER2, and the prognostic power of the reinforced signatures were comparable to that of molecular subtype, stage, tumor size, nodal status, and hormone receptor expression for both DFS and OS. In the multivariate analysis and the stepwise selection for the same parameters, the reinforced signature was found to be an independent prognostic factor for DFS, along with the molecular subtype and the tumor size, and for OS by the inclusion of the molecular subtype, early vs advanced stage, and HER2 expression.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the presence, quantity, and immune contexture of TLS peritumorally, alone, and in combination with intratumoral signatures based on differential densities of CD8 + and CD163 + cells in TC and IM which were recently described by us [8]. This type of analyses provided significant information on the in situ adaptive immune status, introducing improved reinforced biosignatures for clinical outcomes in BCa patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that both, presence and high numbers of peritumoral TLS correlate with unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics and worse prognosis in BCa.

TLS represent structures of varying organization, from simple clusters of lymphocytes to complicated structures with considerable morphological, cellular, and molecular similarities with SLO, particularly lymph nodes [13, 32]. As a consequence of these similarities, HEV, a common characteristic of these structures, may play an important role in the recruitment of circulating lymphocytes to intratumoral TLS [33, 34]. The contribution of TLS to immune control of tumor growth remains speculative. TLS have been detected in the stroma and/or in the invasive margin of tumor in most cancers and their densities mostly correlated with a favorable clinical outcome [9, 16,17,18]. The presence of TLS intratumorally has been correlated with antitumor orientated immune responses, possibly offering an advantage for enhancing the effectiveness of TIL [13, 33]. TLS-associated dendritic cells, by presenting tumor antigenic peptides to T cells located in the T cell compartments of TLS, are key to mount local T cell-mediated antitumor responses [33]. In addition, the presence of CD4 + T cells within TLS further strengthens the notion of a supportive role of TLS for CD8 + effector TIL differentiation [35]. However, TLS may also have a negative impact on cancer prognosis. The presence of Treg in TLS may negatively affect the levels of activation of CD4 + and CD8 + immune infiltrates, resulting in tumor escape from immune surveillance [26]. Furthermore, immunosuppressive B cells, adjacent to CD8 + T cells, in lymphoid follicle-like structures were detected in prostate cancer specimens [36].

The role of peritumoral, outside the invasive margin, TLS has been much less investigated and in BCa there are limited results regarding their prognostic value. Our results show that the presence of peritumoral TLS significantly correlates with histological grade 3 tumors, in accordance with other studies in BCa and urothelial bladder carcinoma [24, 37]. We additionally show that BCa patients with invasive ductal carcinoma, independently of the molecular subtype, having peritumoral TLS exhibit worse DFS and OS than those lacking TLS. This unfavorable prognosis depends both on the location (adjacent only vs adjacent and/or distal) and density (0, 1–4 and > 5) of peritumoral TLS. Liu et al. [24] have recently reported that the presence of TLS, at the invasive margin and/or peritumorally, was associated with a better DFS, but not OS, in a subset of BCa patients, namely those expressing HER2, whereas no differences could be detected in terms of both OS and DFS in HER2 − patients. As no patient lacking TLS in our HER2 + cohort was observed, this finding could not be evaluated in the present study. The difference in TLS-negative HER2 + patients could be attributed to the fact that in our study only patients with primary ductal invasive cancer, no stage IIIB and without neoadjuvant treatment were enrolled, whereas in Liu et al. study patients with any type of primary invasive breast cancer were included.

Our recent work shows that intratumoral high densities of CD8 + cells in the IM, but not in the TC, predicted poor prognosis in BCa patients [8]. Considering these findings, together with the poor prognosis of peritumoral TLS described herein, we could make the hypothesis that immune elements located in the IM or peritumorally may reflect a progressive migration of malignant cells from the TC to the outer areas of the tumor related to invasion and metastasis. This hypothesis could hold true given that we, and others [24], have detected a number of peritumoral TLS infiltrated with clusters of cancer cells. Furthermore, extratumoral TLS were found to be associated with advanced disease in colorectal cancer [38]. In line with this, Finkin et al. reported that inflammation-associated TLS serve as niches for tumor progenitor cells, which may lead to recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma, suggesting an unfavorable prognostic role for peritumoral TLS [27], in contrast to the favorable ones described for intratumoral TLS, thus far in hepatocellular carcinomas [39]. Τhus, peripheral TLS may contribute to an immunosuppressive milieu, supporting tumor growth through negative effects on antitumor immunity, or via direct supportive effects on tumor [40].

Besides the distribution of TLS (intratumorally/peritumorally), an additional parameter to be considered is the “quality” of TLS. The initial TLS formation is followed by a sequence of maturation stages, which probably reflect different functionalities [13, 41]. Studies focusing on the infiltration of TLS attributed their immunosuppressive role to the infiltrating immune cells [26, 36]. In BCa, Tregs within lymphoid infiltrates surrounding the tumor were found to correlate with increased risk for relapse and death [42]. Our results show that RUCIS patients have higher amount of infiltrating FOXP3 + cells in their TLS than the RFCIS patients. Such FOXP3 + cell-containing TLS could promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment leading to shorter survival. Taken altogether, we may propose that the formation, presence, and quality of TLS substantially contribute to the heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment and may explain the differences among intratumoral and peritumoral TLS, a hypothesis requiring further investigation.

In our study, the presence and the density of peritumoral TLS are not independent predictors for DFS and OS in BCa. For this reason, by combining the intratumoral spatial distribution of CD8 + and CD163 + cells in TC and IM with the number of peritumoral TLS in BCa patients, we aimed to create more robust “reinforced signatures”. These signatures do not necessarily mean established signatures (this remains to be validated in future studies with larger cohorts of patients), but rather combined signatures with higher prognostic value compared to the individual signatures from which they were composed. Even though our recently described signature, based on the differential CD8 + and CD163 + cell distribution in the TC and IM, was an independent factor for both DFS and OS in invasive ductal BCa, there was a considerable group (about 50%) of “gray zone” patients (REST group) who could not be classified either in the FCIS or the UCIS group. After combining the intratumoral and peritumoral microenvironment components (TC, IM, and aTLS), we managed to stratify more accurately the patients, creating two new signatures: Reinforced FCIS (RFCIS) and Reinforced UCIS (RUCIS), with an even more powerful prognostic value versus our previously reported signatures [8]. The reinforced signatures described herein constitute an independent prognostic factor, along with the molecular subtype and the tumor size for DFS, and for OS together with molecular subtype, early vs advanced stage and HER2 expression.

Conclusions

In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time an association between spatial differential densities of intratumoral immune infiltrates with peritumoral TLS and clinical outcomes. Our observations further support the existence of a dynamic interplay between the immune cells within the intratumoral microenvironment (TC, IM) and its surrounding counterpart (TLS). Despite the limitations of our study (particularly the small cohort of patients and the elusive determination of the maturational stage of TLS), there is strong evidence supporting the fundamental role of the relationship between tumor microenvironment components for clinical responses. Further studies οn the cellular and molecular mechanisms leading to TLS formation, governing their functions and distinguishing TLS with anti- or pro-tumor activity, are required to thoroughly enlighten their role.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- aTLS:

-

Adjacent tertiary lymphoid structure

- BCa:

-

Breast cancer

- DAB:

-

Diaminobenzidine

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- dTLS:

-

Distant tertiary lymphoid structure

- FCIS:

-

Favorable combined immune signature

- FFPE:

-

Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded

- HEV:

-

High endothelial venule

- HH:

-

High/high

- HL:

-

High/low

- IM:

-

Invasive margin

- LH:

-

Low/high

- LL:

-

Low/low

- RFCIS:

-

Reinforced favorable combined immune signature

- RUCIS:

-

Reinforced unfavorable combined immune signature

- SLO:

-

Secondary lymphoid organ

- TC:

-

Tumor center

- TLS:

-

Tertiary lymphoid structure

- Treg:

-

T regulatory cell

- UCIS:

-

Unfavorable combined immune signature

References

Galluzzi L, Vacchelli E, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Buque A, Senovilla L, Baracco EE, Bloy N, Castoldi F, Abastado JP, Agostinis P, Apte RN, Aranda F, Ayyoub M, Beckhove P, Blay JY, Bracci L, Caignard A, Castelli C, Cavallo F, Celis E, Cerundolo V, Clayton A, Colombo MP, Coussens L, Dhodapkar MV, Eggermont AM, Fearon DT, Fridman WH, Fucikova J, Gabrilovich DI, Galon J, Garg A, Ghiringhelli F, Giaccone G, Gilboa E, Gnjatic S, Hoos A, Hosmalin A, Jager D, Kalinski P, Karre K, Kepp O, Kiessling R, Kirkwood JM, Klein E, Knuth A, Lewis CE, Liblau R, Lotze MT, Lugli E, Mach JP, Mattei F, Mavilio D, Melero I, Melief CJ, Mittendorf EA, Moretta L, Odunsi A, Okada H, Palucka AK, Peter ME, Pienta KJ, Porgador A, Prendergast GC, Rabinovich GA, Restifo NP, Rizvi N, Sautes-Fridman C, Schreiber H, Seliger B, Shiku H, Silva-Santos B, Smyth MJ, Speiser DE, Spisek R, Srivastava PK, Talmadge JE, Tartour E, Van Der Burg SH, Van Den Eynde BJ, Vile R, Wagner H, Weber JS, Whiteside TL, Wolchok JD, Zitvogel L, Zou W, Kroemer G (2014) Classification of current anticancer immunotherapies. Oncotarget 5(24):12472–12508. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2998

Zinzindohoue F, Zeitoun G, Berger A, Todosi AM, Marliot F, Lagorce C, Galon J, Pages F (2014) Immunology and personalized medicine in oncology. Bull Cancer 101(Suppl 1):S12–S17. https://doi.org/10.1684/bdc.2014.1972

Ribas A, Wolchok JD (2018) Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 359(6382):1350–1355. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar4060

Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, Vonderheide RH, Pittet MJ, Jain RK, Zou W, Howcroft TK, Woodhouse EC, Weinberg RA, Krummel MF (2018) Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med 24(5):541–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x

Keren L, Bosse M, Marquez D, Angoshtari R, Jain S, Varma S, Yang SR, Kurian A, Van Valen D, West R, Bendall SC, Angelo M (2018) A structured tumor-immune microenvironment in triple negative breast cancer revealed by multiplexed ion beam imaging. Cell 174(6):1373–1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.039

Pages F, Mlecnik B, Marliot F, Bindea G, Ou FS, Bifulco C, Lugli A, Zlobec I, Rau TT, Berger MD, Nagtegaal ID, Vink-Borger E, Hartmann A, Geppert C, Kolwelter J, Merkel S, Grutzmann R, Van den Eynde M, Jouret-Mourin A, Kartheuser A, Leonard D, Remue C, Wang JY, Bavi P, Roehrl MHA, Ohashi PS, Nguyen LT, Han S, MacGregor HL, Hafezi-Bakhtiari S, Wouters BG, Masucci GV, Andersson EK, Zavadova E, Vocka M, Spacek J, Petruzelka L, Konopasek B, Dundr P, Skalova H, Nemejcova K, Botti G, Tatangelo F, Delrio P, Ciliberto G, Maio M, Laghi L, Grizzi F, Fredriksen T, Buttard B, Angelova M, Vasaturo A, Maby P, Church SE, Angell HK, Lafontaine L, Bruni D, El Sissy C, Haicheur N, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Lagorce C, Meyers JP, Paustian C, Feng Z, Ballesteros-Merino C, Dijkstra J, van de Water C, van Lent-van Vliet S, Knijn N, Musina AM, Scripcariu DV, Popivanova B, Xu M, Fujita T, Hazama S, Suzuki N, Nagano H, Okuno K, Torigoe T, Sato N, Furuhata T, Takemasa I, Itoh K, Patel PS, Vora HH, Shah B, Patel JB, Rajvik KN, Pandya SJ, Shukla SN, Wang Y, Zhang G, Kawakami Y, Marincola FM, Ascierto PA, Sargent DJ, Fox BA, Galon J (2018) International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet 391(10135):2128–2139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30789-X

Schauer D, Starlinger P, Zajc P, Alidzanovic L, Maier T, Buchberger E, Pop L, Gruenberger B, Gruenberger T, Brostjan C (2014) Monocytes with angiogenic potential are selectively induced by liver resection and accumulate near the site of liver regeneration. BMC Immunol 15:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-014-0050-3

Fortis SP, Sofopoulos M, Sotiriadou NN, Haritos C, Vaxevanis CK, Anastasopoulou EA, Janssen N, Arnogiannaki N, Ardavanis A, Pawelec G, Perez SA, Baxevanis CN (2017) Differential intratumoral distributions of CD8 and CD163 immune cells as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer. J Immunother Cancer 5:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-017-0240-7

Sautes-Fridman C, Lawand M, Giraldo NA, Kaplon H, Germain C, Fridman WH, Dieu-Nosjean MC (2016) Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancers: prognostic value, regulation, and manipulation for therapeutic intervention. Front Immunol 7:407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00407

Cipponi A, Mercier M, Seremet T, Baurain JF, Theate I, van den Oord J, Stas M, Boon T, Coulie PG, van Baren N (2012) Neogenesis of lymphoid structures and antibody responses occur in human melanoma metastases. Cancer Res 72(16):3997–4007. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1377

Jones GW, Hill DG, Jones SA (2016) Understanding immune cells in tertiary lymphoid organ development: it is all starting to come together. Front Immunol 7:401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00401

Ager A (2017) High endothelial venules and other blood vessels: critical regulators of lymphoid organ development and function. Front Immunol 8:45. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00045

Colbeck EJ, Ager A, Gallimore A, Jones GW (2017) Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer: drivers of antitumor immunity, immunosuppression, or bystander sentinels in disease? Front Immunol 8:1830. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01830

Noort AR, van Zoest KP, van Baarsen LG, Maracle CX, Helder B, Papazian N, Romera-Hernandez M, Tak PP, Cupedo T, Tas SW (2015) Tertiary lymphoid structures in rheumatoid arthritis: NF-kappaB-inducing kinase-positive endothelial cells as central players. Am J Pathol 185(7):1935–1943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.03.012

Pipi E, Nayar S, Gardner DH, Colafrancesco S, Smith C, Barone F (2018) Tertiary lymphoid structures: autoimmunity goes local. Front Immunol 9:1952. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01952

Di Caro G, Bergomas F, Grizzi F, Doni A, Bianchi P, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P, Mantovani A, Marchesi F (2014) Occurrence of tertiary lymphoid tissue is associated with T-cell infiltration and predicts better prognosis in early-stage colorectal cancers. Clin Cancer Res 20(8):2147–2158. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2590

Ladanyi A, Sebestyen T, Mohos A, Liszkay G, Somlai B, Toth E, Timar J (2014) Ectopic lymphoid structures in primary cutaneous melanoma. Pathol Oncol Res 20(4):981–985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-014-9784-8

Schweiger T, Berghoff AS, Glogner C, Glueck O, Rajky O, Traxler D, Birner P, Preusser M, Klepetko W, Hoetzenecker K (2016) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte subsets and tertiary lymphoid structures in pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 33(7):727–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-016-9813-y

Lin L, Hu X, Zhang H, Hu H (2019) Tertiary lymphoid organs in cancer immunology: mechanisms and the new strategy for immunotherapy. Front Immunol 10:1398. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01398

Dieu-Nosjean MC, Goc J, Giraldo NA, Sautes-Fridman C, Fridman WH (2014) Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol 35(11):571–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2014.09.006

Fridman WH, Zitvogel L, Sautes-Fridman C, Kroemer G (2017) The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14(12):717–734. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.101

Lee HJ, Kim JY, Park IA, Song IH, Yu JH, Ahn JH, Gong G (2015) Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and the tertiary lymphoid structures in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with adjuvant trastuzumab. Am J Clin Pathol 144(2):278–288. https://doi.org/10.1309/AJCPIXUYDVZ0RZ3G

Lee HJ, Park IA, Song IH, Shin SJ, Kim JY, Yu JH, Gong G (2016) Tertiary lymphoid structures: prognostic significance and relationship with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Pathol 69(5):422–430. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203089

Liu X, Tsang JYS, Hlaing T, Hu J, Ni YB, Chan SK, Cheung SY, Tse GM (2017) Distinct tertiary lymphoid structure associations and their prognostic relevance in HER2 positive and negative breast cancers. Oncologist 22(11):1316–1324. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0029

Figenschau SL, Fismen S, Fenton KA, Fenton C, Mortensen ES (2015) Tertiary lymphoid structures are associated with higher tumor grade in primary operable breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 15:101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1116-1

Joshi NS, Akama-Garren EH, Lu Y, Lee DY, Chang GP, Li A, DuPage M, Tammela T, Kerper NR, Farago AF, Robbins R, Crowley DM, Bronson RT, Jacks T (2015) Regulatory T cells in tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures suppress anti-tumor T cell responses. Immunity 43(3):579–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.006

Finkin S, Yuan D, Stein I, Taniguchi K, Weber A, Unger K, Browning JL, Goossens N, Nakagawa S, Gunasekaran G, Schwartz ME, Kobayashi M, Kumada H, Berger M, Pappo O, Rajewsky K, Hoshida Y, Karin M, Heikenwalder M, Ben-Neriah Y, Pikarsky E (2015) Ectopic lymphoid structures function as microniches for tumor progenitor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol 16(12):1235–1244. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3290

Pages F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Asslaber M, Tosolini M, Bindea G, Lagorce C, Wind P, Marliot F, Bruneval P, Zatloukal K, Trajanoski Z, Berger A, Fridman WH, Galon J (2009) In situ cytotoxic and memory T cells predict outcome in patients with early-stage colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(35):5944–5951. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6147

Vingiani A, Viale G (2017) The pathology report. In: Veronesi U, Goldhirsch A, Veronesi P, Gentilini OD, Leonardi MC (eds) Breast cancer: innovations in research and management. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48848-6_16

Buisseret L, Desmedt C, Garaud S, Fornili M, Wang X, Van den Eyden G, de Wind A, Duquenne S, Boisson A, Naveaux C, Rothe F, Rorive S, Decaestecker C, Larsimont D, Piccart-Gebhart M, Biganzoli E, Sotiriou C, Willard-Gallo K (2017) Reliability of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte and tertiary lymphoid structure assessment in human breast cancer. Mod Pathol 30(9):1204–1212. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.43

Pedersen L, Gunnarsdottir KA, Rasmussen BB, Moeller S, Lanng C (2004) The prognostic influence of multifocality in breast cancer patients. Breast 13(3):188–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2003.11.004

Engelhard VH, Rodriguez AB, Mauldin IS, Woods AN, Peske JD, Slingluff CL Jr (2018) Immune cell infiltration and tertiary lymphoid structures as determinants of antitumor immunity. J Immunol 200(2):432–442. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1701269

Goc J, Germain C, Vo-Bourgais TK, Lupo A, Klein C, Knockaert S, de Chaisemartin L, Ouakrim H, Becht E, Alifano M, Validire P, Remark R, Hammond SA, Cremer I, Damotte D, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C, Dieu-Nosjean MC (2014) Dendritic cells in tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures signal a Th1 cytotoxic immune contexture and license the positive prognostic value of infiltrating CD8 + T cells. Cancer Res 74(3):705–715. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1342

Nerviani A, Pitzalis C (2018) Role of chemokines in ectopic lymphoid structures formation in autoimmunity and cancer. J Leukoc Biol 104(2):333–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/JLB.3MR0218-062R

de Chaisemartin L, Goc J, Damotte D, Validire P, Magdeleinat P, Alifano M, Cremer I, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C, Dieu-Nosjean MC (2011) Characterization of chemokines and adhesion molecules associated with T cell presence in tertiary lymphoid structures in human lung cancer. Cancer Res 71(20):6391–6399. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0952

Shalapour S, Font-Burgada J, Di Caro G, Zhong Z, Sanchez-Lopez E, Dhar D, Willimsky G, Ammirante M, Strasner A, Hansel DE, Jamieson C, Kane CJ, Klatte T, Birner P, Kenner L, Karin M (2015) Immunosuppressive plasma cells impede T-cell-dependent immunogenic chemotherapy. Nature 521(7550):94–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14395

Koti M, Xu AS, Ren KYM, Visram K, Ren R, Berman DM, Siemens DR (2017) Tertiary lymphoid structures associate with tumour stage in urothelial bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer 3(4):259–267. https://doi.org/10.3233/BLC-170120

Bento DC, Jones E, Junaid S, Tull J, Williams GT, Godkin A, Ager A, Gallimore A (2015) High endothelial venules are rare in colorectal cancers but accumulate in extra-tumoral areas with disease progression. Oncoimmunology 4(3):e974374. https://doi.org/10.4161/2162402X.2014.974374

Calderaro J, Petitprez F, Becht E, Laurent A, Hirsch TZ, Rousseau B, Luciani A, Amaddeo G, Derman J, Charpy C, Zucman-Rossi J, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C (2019) Intra-tumoral tertiary lymphoid structures are associated with a low risk of early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 70(1):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.003

Butterfield LH, Kaufman HL, Marincola FM (2017) Cancer immunotherapy principles and practice. Demos Medical Publishing, New York

Posch F, Silina K, Leibl S, Mundlein A, Moch H, Siebenhuner A, Samaras P, Riedl J, Stotz M, Szkandera J, Stoger H, Pichler M, Stupp R, van den Broek M, Schraml P, Gerger A, Petrausch U, Winder T (2018) Maturation of tertiary lymphoid structures and recurrence of stage II and III colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 7(2):e1378844. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2017.1378844

Gobert M, Treilleux I, Bendriss-Vermare N, Bachelot T, Goddard-Leon S, Arfi V, Biota C, Doffin AC, Durand I, Olive D, Perez S, Pasqual N, Faure C, Ray-Coquard I, Puisieux A, Caux C, Blay JY, Menetrier-Caux C (2009) Regulatory T cells recruited through CCL22/CCR42 are selectively activated in lymphoid infiltrates surrounding primary breast tumors and lead to an adverse clinical outcome. Cancer Res 69(5):2000–2009. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2360

Funding

This study was supported by Grant GER_1968 (acronym ISPEBREAST) to Constantin N. Baxevanis from the Greek–German bilateral cooperation for research and innovation, funded by the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (GSRT) of the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs of the Hellenic Republic and the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), and by a donation to Sonia Perez from the Haegeman-Goossens family, Netherlands. We would like to acknowledge the Haegeman-Goossens family for their support to our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and SPF equally contributed to study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and the writing the manuscript; CKV contributed to the study design, data collection, and interpretation of results; NNS contributed to data collection and analysis; AA and NA were responsible for the collection of patient material and clinical follow-up; DV contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript; SAP and CNB supervised the study, contributed to experimental design, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and ethical standards

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Savas Cancer Hospital, Study code: IRB-ID 6079/448/10-6-13. Date of approval: 10/06/2013; retrospective study (2000–2010); first patient prospectively enrolled: 14/2/2014.

Informed consent

Retrospectively analyzed (2000–2010) and prospectively enrolled patients (2014–2015) who signed the same informed consent. Individual participants provided written informed consent for the use of their specimens. In cases where retrospectively analyzed patients could not visit the hospital to provide signed informed consent, they were informed orally via telephone calls by their oncologists. Clinical data were obtained from all patients anonymously. Patients were assured that confidentiality of their records will be protected according to the Greek regulations and laws.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sofopoulos, M., Fortis, S.P., Vaxevanis, C.K. et al. The prognostic significance of peritumoral tertiary lymphoid structures in breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 68, 1733–1745 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-019-02407-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-019-02407-8