Abstract

The objective of the present study was to determine whether an analysis of two-phase spiral computed tomographic (CT) features provides a sound basis for the differential diagnosis between gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis. Eighty-two patients, 35 with gallbladder carcinoma and 47 with chronic cholecystitis, underwent two-phase spiral CT. We reviewed the two-phase spiral CT features of thickness and enhancement pattern of the gallbladder wall seen during the arterial and venous phases. Mean wall thicknesses were 12.6 mm in the gallbladder carcinoma group and 6.9 mm in the chronic cholecystitis group. The common enhancement patterns seen in gallbladder carcinoma were (a) a highly enhanced thick inner wall layer during the arterial phase that showed isoattenuation with the adjacent hepatic parenchyma during the venous phase (16 of 35, 45.7%) and (b) a highly enhanced thick inner wall layer during both phases (eight of 35, 22.9%). The most common enhancement pattern of chronic cholecystitis was isoattenuation of the thin inner wall layer during both phases (42 of 47, 89.4%). In conclusion, awareness of the wall thickening and enhancement patterns in gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis on two-phase spiral CT appears to be valuable in differentiating these two different disease entities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Differentiation between gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis has been an important clinical issue because the procedures involved in the prognosis and management of gallbladder carcinoma and cholecystitis differ. Because the clinical manifestations of gallbladder carcinoma are nonspecific and often indistinguishable from those of chronic cholecystitis, the accurate preoperative diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma is difficult. Thus, it is important that the radiologist be able to differentiate gallbladder carcinoma from chronic cholecystitis [1 2 3 4 5 6 7]. Despite the efforts of many previous investigators [8 9], early diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma and differentiation between malignancy and an inflammatory process remain problematic.

Compared with incremental computed tomography (CT), spiral CT offers the advantages of faster scan times, smaller interscan intervals, and optimization of the use of contrast medium [10]. To our knowledge, no previously published investigation has focused on the differential diagnosis between gallbladder carcinoma and an inflammatory process of the gallbladder by means of two-phase spiral CT.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the two-phase spiral CT features of gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis and to determine whether the two diseases could be successfully differentiated through analysis of their two-phase spiral CT features.

Materials and Methods

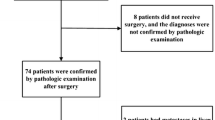

We obtained a computer-generated list of all contrast-enhanced examinations done at our institution between March 1997 and May 2000, with findings suggestive of pathologic conditions of the gallbladder. If diffuse gallbladder wall thickening had been detected by an ultrasound examination and patients complained of acute symptoms, acute cholecystitis might have been diagnosed in such patients and cholecystectomy performed before two-phase spiral CT was undertaken. These cases were excluded from our series. With findings of unusual wall thickening or a focal mass in the gallbladder on an ultrasound examination, two-phase spiral CT was recommended to differentiate the gallbladder carcinoma from the chronic cholecystitis. On the basis of categories established by previous investigators [3 7 9 10], lesions suggesting gallbladder carcinoma were classified as having diffuse or focal wall thickening, as a polypoid mass, or as a mass replacing the gallbladder. Cases of a mass replacing the gallbladder were excluded when subjects were selected using CT findings, because we wanted to pay special attention to the thickness and enhancement pattern of the gallbladder wall.

In 26 of the 41 patients with suspected carcinoma and 468 of the 482 with suspected cholecystitis, the respective conditions were confirmed by histopathologic examination after cholecystectomy; in the remaining 15 with suspected carcinoma, this was confirmed by biopsy. Thirty-five of the 41 with confirmed gallbladder carcinoma and 47 with chronic cholecystitis of the 468 with confirmed cholecystitis (42 males and 40 females, mean age ± standard deviation = 59 ± 12 years) underwent two-phase spiral CT, and these 82, in whom the respective conditions had been pathologically proven, were included in our series.

CT examinations were obtained with the Hi-Speed Advantage System (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Our protocol consisted of 120 mL of iohexol (300 mg I/mL; Omnipaque, Nycomed Ireland Ltd., Cork, Ireland) injected intravenously at a rate of 2–3 mL/s by power injector. The table increment speed was 5 mm/s, with 5-mm collimation. After data acquisition, contiguous axial reconstructions were obtained every 7 mm. Two-phase spiral CT scans were obtained at the arterial and venous phases, 35 and 65 s, respectively, after the initiation of contrast material injection. All patients fasted for at least 6 h before CT.

We retrospectively reviewed the two-phase spiral CT findings, paying special attention to the thickness of the gallbladder wall, the type of wall thickening, and the enhancement pattern seen on arterial and venous phase scans. Normal gallbladder wall was seen as isoattenuation in relation to that of the adjacent hepatic parenchyma in the arterial and venous phases. We also analyzed associated findings such as invasion of the liver, pericholecystic fat infiltration, dilatation of intrahepatic ducts, enlargement of lymph nodes to more than 1 cm in long diameter, the presence of gallstones and ascites, distant metastasis, and pericholecystic fluid collection. The thickness of the gallbladder wall was measured at its most hypertrophied portion, including all visible layers on the venous phase scans, manually at the operating console of CT. The enhancement pattern of wall thickening was classified by comparing the degree of enhancement of the thickened wall, as seen during the arterial and venous phases, with that of adjacent hepatic parenchyma.

Two-phase spiral CT scans were reviewed by two radiologists whose decisions were reached by consensus. For statistical analysis, Student’s t test and chi-square test were used, together with SPSS-PC 9.0 on a personal computer.

Results

The results of cases with gallbladder carcinoma in our series, excluding cases of a mass replacing the gallbladder, showed that focal or diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall was more frequent (22 of 35, 62.9%) than a polypoid mass originating in the gallbladder wall.

Mean wall thicknesses in the gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis groups were 12.6 mm and 6.9 mm in the arterial and venous phases, respectively. The thickness of the gallbladder wall measured in the arterial phase was not different from that in the venous phase. The greater thickness found in the former group was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Irregular wall thickening was more frequent in patients with gallbladder carcinoma (20 of 35, 57.1%) than in those with chronic cholecystitis (13 of 47, 27.7%).

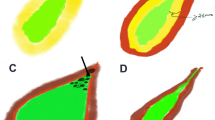

The various enhancement patterns of wall thickening seen in gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis are listed in Table 1. For gallbladder carcinoma, the most common enhancement patterns were (a) a highly enhanced thick inner wall layer seen during the arterial phase that showed isoattenuation with adjacent hepatic parenchyma during the venous phase (16 of 35, 45.7%; Fig. 1) and (b) a highly enhanced thick inner wall layer seen during the arterial and venous phases (eight of 35, 22.9%; Fig. 2). For chronic cholecystitis, the most common enhancement pattern was an isoattenuation of the thin inner wall layer during the arterial and venous phases (42 of 47, 89.4%; Fig. 3).

Findings of intrahepatic mass formation by direct invasion (nine of 35), lymph node enlargement (12 of 35), and metastasis to other organs (seven of 35) were demonstrated only in cases of gallbladder carcinoma, whereas dilatation of intrahepatic ducts was seen more frequently in cases of gallbladder carcinoma (18 of 35, 51.4%) than of chronic cholecystitis (10 of 47, 21.3%). The incidences of pericholecystic fat infiltration, pericholecystic fluid collection, and ascites did not differ significantly between the gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis groups. Gallstones were more frequent in patients with chronic cholecystitis than in those with gallbladder carcinoma (Table 2).

Discussion

A general awareness of the radiologic features of gallbladder carcinoma will enhance the preoperative diagnosis. Gallbladder carcinoma as seen on cross-sectional images may follow one of three major patterns: (a) a mass obscuring or replacing the gallbladder, (b) focal or diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall, and (c) a polypoid mass originating in the gallbladder wall and projecting into the lumen [3, 7, 9, 10]. Several previous investigators reported that focal or diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall among these three types was the least common presentation [3, 10, 11]. The results of cases with gallbladder carcinoma in our series, excluding cases of a mass replacing the gallbladder, showed that focal or diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall is more frequent (22 of 35, 62.9%) than is a polypoid mass originating in the gallbladder wall.

The differential diagnoses of infiltrating gallbladder carcinoma include complicated cholecystitis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastasis to the gallbladder fossa. Clinically and radiologically, gallbladder carcinoma may be difficult to differentiate from cholecystitis with pericholecystic fluid and abscess [10]. Diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall secondary to uniform infiltration by a tumor can be similar in appearance to chronic cholecystitis, and this appearance is nonspecific [3]. Focal thickening of the gallbladder wall may indicate the involvement of malignancy. Focal thickening is difficult to differentiate from an area of fibrosis associated with chronic cholecystitis or an area of adenomatous hyperplasia. However, a wall infiltrated by malignancy is typically thicker and more irregular than one thickened by inflammation, and the thicker and more irregular wall has suggested malignancy [11, 12]. The results of our study showed that thicker and more irregular wall thickening is more frequent in patients with gallbladder carcinoma (20 of 35, 57.1%) than in those with chronic cholecystitis (13 of 47, 27.7%).

Although ultrasound is widely accepted for imaging the gallbladder and CT is thought to complement its findings, awareness of the two-phase spiral CT features of gallbladder diseases is useful for diagnosis. In our study, the thickness of the gallbladder wall measured in the arterial phase did not differ from that in the venous phase. However, the enhancement patterns of the gallbladder wall thickening in the arterial phase did differ from those in the venous phase. The finding of highly enhanced thick inner wall layer seen during the arterial phase, which showed isoattenuation or high attenuation in relation to adjacent hepatic parenchyma during the venous phase, strongly suggested malignancy, and isoattenuation of the thin inner wall layer during the arterial and venous phases was a more frequent feature of chronic cholecystitis. Therefore, enhancement patterns of gallbladder wall thickening in the arterial and venous phases should be helpful in differentiating gallbladder carcinoma from chronic cholecystitis when using two-phase spiral CT. Two-phase spiral CT is more useful than conventional CT for the differential diagnosis between these two disease entities. Thus, awareness of the type of wall thickening and enhancement patterns in gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis on two-phase spiral CT appears to be valuable in differentiating these two entities.

The most common route of dissemination for gallbladder carcinoma is direct invasion of the liver, which can be explained by the fact that the hepatic surface of the gallbladder is drained by vessels that communicate with adjacent hepatic veins; spread through this route leads to involvement of the adjacent liver [13]. Spread to lymph nodes around the cystic and pericholedochal nodes is also common [14]. Other structures that may be involved are the lymph nodes (porta hepatis, hepatic and common bile ducts), pancreas, colon, and duodenum. In our series, direct invasion of the liver was apparent in nine of the 35 patients with gallbladder carcinoma (25.7%), and 12 of the 35 (34.3%) had demonstrated lymph node enlargement in cystic (n = 7), pericholedochal (n = 5), porta hepatic (n = 4), and pancreatoduodenal (n = 3) regions. Direct or lymphatic spread of malignancy to the porta hepatis results in obstruction of the biliary tree, which is manifested as jaundice. Although this is one of the earliest clinical manifestations of the disease, it unfortunately signifies an advanced stage of malignancy. In this study, 18 patients (51.4%) presented with dilatation of the biliary tree due to tumor invasion of the common bile duct (n = 5) and the intrahepatic duct (n = 4) at the bifurcation level and to lymph node enlargement in the porta hepatis (n = 8) and pericholedochal region (n = 1).

The risk of gallbladder carcinoma is greater in patients with gallstones. The prevalence of gallstone in cases of gallbladder carcinoma has been reported as approximately 73–98% [15]. In the present study, six cases (of 35, 17.1%) of gallstones were identified radiologically in the gallbladder carcinoma group. This low prevalence of associated gallstone is thought to be due to bias in the selection of patients.

In summary, the results of this study showed that, if a highly attenuated thick inner wall layer of gallbladder is seen during the arterial phase and this layer shows isoattenuation or high attenuation during the venous phase, malignancy is likely; conversely, if isoattenuation of the thin inner wall layer is seen during the arterial and venous phases, then chronic cholecystitis is more likely than gallbladder carcinoma. Findings of liver invasion, regional lymph node enlargement, and distant metastasis strongly suggest gallbladder carcinoma.

Gallbladder carcinoma with high isoattenuation relative to the focal thick inner wall layer of the gallbladder at two-phase spiral CT. A Image during the arterial phase of spiral CT shows that the focally thickened inner wall layer of gallbladder is strongly enhanced (arrow). B Image during the venous phase shows that the same lesion shows isoattenuation with the adjacent hepatic parenchyma (arrow).

References

RL Smathers JK Lee JP Heiken (1984) ArticleTitle Differentiation of complicated cholecystitis from gallbladder carcinoma by computed tomography AJR 143 255–259 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BiuB2Mzkt1Q%3D Occurrence Handle6611051

AH Dachman (1994) Benign and malignant tumors of the gallbladder. AC Friedman AH Dachman (Eds) Radiology of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas, 1st ed. Mosby-Year Book St Louis 555–576

SA Rooholamini NS Tehrani MK Razavi et al. (1994) ArticleTitle Imaging of gallbladder carcinoma Radiographics 14 291–306 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:ByuB2cfjvV0%3D Occurrence Handle8190955

R Maeyama K Yamaguchi H Noshiro et al. (1998) ArticleTitle A large inflammatory polyp of the gallbladder masquerading as gallbladder carcinoma J Gastroenterol 33 770–774 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s005350050172 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1cvksV2gsQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9773949

H Onoyama M Yamamoto M Takada et al. (1999) ArticleTitle Diagnostic imaging of early gallbladder cancer: retrospective study of 53 cases World J Surg 23 708–712 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1Mzit1agtA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10390591

KA Chun HK Ha ES Yu et al. (1997) ArticleTitle Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: CT features with emphasis on differentiation from gallbladder carcinoma Radiology 203 93–97 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:ByiB3s3ktVE%3D Occurrence Handle9122422

Y Tsuchiya (1991) ArticleTitle Early carcinoma of the gallbladder: Macroscopic features and US findings Radiology 179 171–175 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:By6C2s3pvFU%3D Occurrence Handle2006272

RK Zeman RL Baron RB Jeffrey Jr et al. (1998) ArticleTitleHelical body CT: evolution of scanning protocols AJR 170 1427–1438 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c3ntVeisA%3D%3D Occurrence Handle9609149

SN Weiner M Koenigsberg H Morehouse J Hoffman (1984) ArticleTitle Sonography and computed tomography in the diagnosis of carcinoma of the gallbladder AJR 142 735–739 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BiuC2M%2Fjt1c%3D Occurrence Handle6608233

RM Gore MS Levine (2000) Neoplasms of the gallbladder and biliary tract. EM Ward AS Fulcher FS Pereles RM Gore (Eds) Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology, 2nd ed. WB Saunders Philadelphia 1360–1374

J Lane JL Buck RK Zeman (1989) ArticleTitle Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder: a pictorial essay Radiographics 9 209–228 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BiaC1crnsV0%3D Occurrence Handle2648501

RB Jeffrey FC Laing W Wong PW Callen (1983) ArticleTitle Gangrenous cholecystitis: diagnosis by ultrasound Radiology 148 219–221 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BiyB383ivFM%3D Occurrence Handle6856839

PJ Fultz J Skucas SL Weiss (1988) ArticleTitle Comparative imaging of gallbladder cancer J Clin Gastroenterol 6 683–692

T Ohtani Y Shirai K Tsukada et al. (1993) ArticleTitle Carcinoma of the gallbladder: CT evaluation of lymphatic spread Radiology 189 875–880 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:ByuD2M3mt1c%3D Occurrence Handle8234719

RA Kane R Jacobs J Katz P Costello (1984) ArticleTitle Porcelain gallbladder: ultrasound and CT appearance Radiology 152 137–141 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BiuB383mvFY%3D Occurrence Handle6729103

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yun, E., Cho, S., Park, S. et al. Gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis: differentiation with two-phase spiral CT. Abdom Imaging 29, 102–108 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-003-0080-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-003-0080-4