Abstract

Purpose

Although specific positron emission tomography (PET) scanners have been developed for small animals, spatial resolution remains one of the most critical technical limitations, particularly in the evaluation of the rodent brain. The purpose of the present study was to examine the reliability of voxel-based statistical analysis (Statistical Parametric Mapping, SPM) applied to 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET images of the rat brain, acquired on a small animal PET not specifically designed for rodents. The gold standard for the validation of the PET results was the autoradiography of the same animals acquired under the same physiological conditions, reconstructed as a 3-D volume and analysed using SPM.

Methods

Eleven rats were studied under two different conditions: conscious or under inhalatory anaesthesia during 18F-FDG uptake. All animals were studied in vivo under both conditions in a dedicated small animal Philips MOSAIC PET scanner and magnetic resonance images were obtained for subsequent spatial processing. Then, rats were randomly assigned to a conscious or anaesthetized group for postmortem autoradiography, and slices from each animal were aligned and stacked to create a 3-D autoradiographic volume. Finally, differences in 18F-FDG uptake between conscious and anaesthetized states were assessed from PET and autoradiography data by SPM analysis and results were compared.

Results

SPM results of PET and 3-D autoradiography are in good agreement and led to the detection of consistent cortical differences between the conscious and anaesthetized groups, particularly in the bilateral somatosensory cortices. However, SPM analysis of 3-D autoradiography also highlighted differences in the thalamus that were not detected with PET.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that any difference detected with SPM analysis of MOSAIC PET images of rat brain is detected also by the gold standard autoradiographic technique, confirming that this methodology provides reliable results, although partial volume effects might make it difficult to detect slight differences in small regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) for in vivo imaging of metabolic processes is a powerful tool to study the aetiopathogenesis and progression of neurological diseases and to test the efficacy of new therapeutic agents [1]. Recently, specific PET scanners have been developed for small animals which provide smaller fields of view and higher spatial resolution than clinical tomographs. This allows longitudinal functional neuroimaging studies to be undertaken in animal models of various neurological conditions, including Parkinson’s disease [2, 3], Alzheimer’s disease [4] and epilepsy [5]. Moreover, due to the fact that the same imaging technique can be used for both animal and human studies, methodologies and results obtained from animal models may be easily translated to the clinical setting.

In PET studies of the human brain, voxel-based analysis is the most extensively used methodology for quantification. Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) is the most popular software for this purpose [6]. This software applies a general linear model to each voxel to perform statistical comparisons between images of different subjects. The result is a statistical image that can be used to spatially localize significant information. It should be noted that use of SPM requires that images from different individuals be spatially normalized, that is, mapped into a common stereotaxic space by using a template image as reference. In comparison to traditional analysis using regions of interest (ROIs), SPM is faster and includes the whole brain in the analysis, without any preconception about the structures involved in the investigated pathology. Recently, SPM analysis has also been applied to the study of animal models of different neurological diseases [7, 8], and various templates have been developed for spatial normalization of rodent brains [9, 10].

Although the resolution of small animal-dedicated tomographs has significantly improved, high-resolution autoradiography still represents a key reference tool for functional neuroimaging in small animal research. Autoradiography is a widely available low-cost technique with a spatial resolution approximately one order of magnitude better than even the best small animal PET devices (100–200 μm vs 1–2 mm, respectively) [11]. However, autoradiography requires the sacrifice of the animal, thus negating its use in longitudinal studies. These differences between in vivo small animal PET and autoradiography are widely known, and several studies have compared the results of these two techniques in detail [12–16]. Autoradiography is inherently a two-dimensional (2-D) sampling method in which slices are obtained independently without correspondence between neighbouring slices. Therefore, quantification is classically obtained by the labour-intensive procedure of manually drawing ROIs plane by plane. In order to avoid this drawback, several authors have described different methodologies for voxel-based analysis, all of them based on the creation of a three-dimensional (3-D) volume stack of aligned autoradiographic slices [17–19]. Moreover, these methodologies have been successfully applied in the study of different animal models of neurological pathologies [20, 21].

In this study, the primary objective was to validate statistical voxel-based analysis of PET rat brain studies performed in our Philips MOSAIC small animal PET tomograph, using high-resolution 3-D autoradiography as a reference. To this end, an automated procedure for voxel-based analysis of PET and autoradiography was designed and applied for comparison of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) metabolic studies of the rat brain. For comparative purposes, animals were studied under two different conditions during tracer uptake: conscious and under inhalatory anaesthesia (isoflurane), protocols that have been demonstrated to result in clear differences [22]. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to compare SPM results between 3-D autoradiographic volumes and PET images of the rat brain.

Materials and methods

Animals

Eleven male healthy Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Ibérica, Barcelona, Spain) weighing 253 ±14.5 g were individually housed under light-controlled (12:12 light/dark cycle, with lights on at 08:00 h) and temperature-controlled (22 ± 1°C) conditions. Animals had ad libitum access to food and tap water. Rats were deprived of food for 8 h before both PET and autoradiography studies. The research protocol was approved by the local Animal Ethics Committee (Universidad de Navarra Institutional Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals) and was designed according to European Ethics Committee guidelines (decree 86/609/EEC). All animals were studied with PET, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and autoradiography techniques.

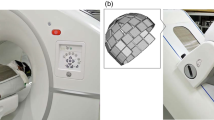

PET studies

18F-FDG PET imaging was performed at Clínica Universidad de Navarra in a dedicated small animal Philips MOSAIC tomograph (Cleveland, OH, USA). This system is based on 14,456 GSO crystals with dimensions of 2 × 2 × 10 mm, arranged in 52 rings of 278 crystals each [23]. The crystals are read out by an hexagonal array of 288 photomultiplier tubes. This gantry design leads to a transverse field of view (FOV) 12.8 cm in diameter and with an axial extent of 12.0 cm, designed to image rodents or larger animals such as primates [24]. The scanner operates exclusively in 3-D mode. A detailed description of this system can be found elsewhere [25]. The radial spatial resolution of this system is 2.7 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) in the radial direction and 3.4 mm FWHM in the axial direction at the centre of the FOV [23].

PET studies were conducted for two conditions in all rats (n = 11): conscious or under inhalatory anaesthesia (2% isoflurane in 100% O2 gas) during the 18F-FDG uptake period. For each animal, PET in the conscious state was performed first and all the studies were completed in a 1-week interval. In both conditions, animals were anaesthetized using isoflurane at the moment of the tracer injection and during the PET studies. Animals were placed prone on the PET scanner bed with their head positioned in the centre of the FOV 30 min after radiotracer administration via the tail vein (20.2 ± 0.3 MBq in 0.2 ml of saline solution) to perform a static acquisition of 15 min. Images were subsequently reconstructed using an iterative 3-D row action maximum likelihood algorithm (3-D RAMLA), with 2 iterations and a relaxation parameter of 0.024. Corrections for dead time, decay, random coincidences and scattering were applied. Images were reconstructed on a 128 × 128 × 120 matrix, where the voxel size equals 1 × 1 × 1 mm. PET images were normalized for the injected dose of 18F-FDG and the animal’s body weight, resulting in parametric images representing the standard uptake value (SUV).

MRI acquisition

MRI studies of the same population of rats were performed at Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) 15 days after PET images. MRI scans were acquired in a BIOSPEC BMT 47/40 scanner (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) operating at 4.7 T and equipped with a 12-cm actively shielded gradient system.

Rats were anaesthetized with the same mixture of oxygen and isoflurane, after which they were placed in a prone position inside a 7-cm birdcage radiofrequency probe head with their head maintained in a fixed position. A respiration sensor was used to control the animals during the scanning procedure. Global shimming was performed, followed by three fast spin-echo scout images in the axial, sagittal and coronal directions to localize the brain. The acquisition parameters for these acquisitions were: repetition time (TR) = 2,100 ms, effective echo time (TE) = 60 ms, FOV = 3.6 × 3.6 cm2 and matrix size = 256 × 128. The acquired data were zero-filled to obtain images of 256 × 256 pixels. The acquisition time for each experiment was 33 s. A 3-D fast spin-echo study was then performed using the following acquisition parameters: TR = 1,600 ms, effective TE = 80 ms, FOV = 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 cm3 and matrix size = 128 × 128 × 64. The reconstructed matrix size was 128 × 128 × 128 and the pixel size was 0.27 × 0.27 × 0.27 mm. The total acquisition time for this experiment was 14 min.

Autoradiography

The regional glucose metabolism of the same animals was evaluated ex vivo by autoradiography at the Brain Mapping Unit of Complutense University of Madrid. Autoradiographic measurements were performed after MRI and were completed in a 1-week interval. 18F-FDG was injected via the tail vein (54.5 ± 2.9 MBq in 0.2 ml of saline solution). The animals were then divided into two groups based on whether they were conscious (n = 5) or under isoflurane anaesthesia (2% in 100% O2; n = 6) during the 30-min tracer uptake period. At the end of the uptake period the animals were sacrificed and their brains were quickly and carefully removed and frozen by immersion in cold isopentane in dry ice. Serial coronal brain sections (40 μm thickness) from the olfactory bulb to the level of the cerebellum were cut at −20°C using a cryostat (Leica CM1850, Nussloch, Germany). One of every five sections was collected, yielding approximately 100 sections per animal, at a separation of 200 μm. The slices were thaw-mounted onto Superfrost Plus® microscope slides (Menzel-Gläser, Braunschweig, Germany), rapidly heat-dried and exposed to an autoradiographic film (Agfa Curix RP2 Plus, Mortsel, Belgium) for 1 h. The films were then manually developed and left to dry in a warm air stream. All the autoradiographically labelled brain slices were digitally captured at a resolution of 1,300 × 1,030 pixels (Leica DC300F, Nussloch, Germany).

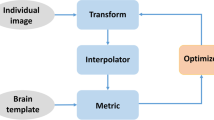

PET analysis

For whole-brain analysis, images from the different rats were spatially normalized into a standard stereotaxic space using the Paxinos and Watson [26] coordinate system (Fig. 1). Although a T2-weighted MRI template has previously been published [10], neither PET nor autoradiography templates were available. Hence, the normalization procedure required an initial step registering each image to the corresponding MRI scan in order to use the MRI rat template.

Taking into account the spatial resolution of our PET images, automatic registration between the PET and MRI scans was not feasible. Therefore, a manual registration process employing PMOD software (version 3.0; PMOD Technologies Ltd., Adliswil, Switzerland) was used, based on MRI including the skull and scalp and using anatomical structures such as the Harderian glands as reference points. Each MRI scan was normalized to Paxinos space (SPM, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK) and the transformation matrix was applied to each PET image and saved for future application. Prior to statistical analysis, a brain mask obtained from each MRI procedure was applied over the PET scan to exclude extracerebral areas. Each of the scans was also individually smoothed with a Gaussian kernel to reduce the impact of misregistration into template space and to improve the signal to noise ratio. The smoothing was performed with a 0.6 mm FWHM filter.

Differences in 18F-FDG uptake between the conscious and anaesthetized state were assessed using SPM8 software, including the 11 animals in the two acquisition conditions. A two-sample paired t test was used to account for the fact that both conditions were obtained from the same animal. To ensure that the analysis only included voxels mapping cerebral tissue, a default threshold of 80% of the mean uptake inside the brain was selected. Global uptake differences between brain scans were adjusted using the “proportional scaling” SPM option.

A significance level threshold of 0.005 (uncorrected for multiple comparisons) and a minimum cluster size of 200 voxels were selected. The size of the clusters exceeding the threshold and their corrected significance were evaluated and anatomically located using an ROI template [27] in Paxinos stereotaxic space.

Creation of a 3-D volume of autoradiography and SPM analysis

The autoradiographic brain images were preprocessed with ImageJ v 1.37 software (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). First, a rectangular bounding box (700 × 500 pixels) was defined around each section (Fig. 2a). The image grey scale was then inverted to conform to the conventions of human functional imaging data (Fig. 2b) and the background was subtracted using a rolling ball algorithm (Fig. 2c). A volume of interest was also drawn as an isocontour over the autoradiographic images to generate a mask of cerebral areas and to remove the possible contribution of adjacent sections (Fig. 2d)

Autoradiographic processing for 3-D volume construction. a Original digital slices. b Conversion of grey scale to inverted colour scale. c Background subtraction. d Application of a mask to eliminate adjacent sections. e Image stack creation. f Alignment and registration of the slices for definitive 3-D volume creation

In order to create a 3-D image, all slices from each animal were imported as an image stack using PMOD (Fig. 2e). Adjacent sections were aligned using the PMOD Image Fusion tool. Due to the fact that the central slices provide the best quality, an appropriately positioned artefact-free central slice was selected as reference. The alignment of the whole volume was then performed sequentially between adjacent slices. To preserve the shape of the sections, a rigid transformation was chosen and the squared difference sum was used as the dissimilarity metric for optimization. After the automatic registration and visual inspection, a slight manual alignment was performed on some slices if necessary. Thus, an autoradiographic 3-D volume was obtained for each animal (Fig. 2f). The fidelity of the alignment and 3-D reconstruction process was assessed by visual inspection of internal structures viewed in different orthogonal sections, as well as by inspection of the smoothness of the cortex after rendering the surface.

The resultant 3-D volume then had to be spatially normalized to a standard space (Fig. 1). As a specific template of autoradiography does not exist, an MRI template was used. For each animal, a mask was applied over its corresponding MRI scan to remove the skull and scalp. Registration between the skull-stripped MRI scan and the 3-D autoradiography image was performed automatically, followed by visual inspection and manual adjustment only if necessary. The previously calculated transformation matrix of MRI normalization was then applied to the autoradiographic 3-D volume of the same animal (SPM8).

As previously done with the PET data, 3-D autoradiographic volumes were smoothed with a Gaussian filter with FWHM of 1 mm. As each animal is only acquired in one condition, a two sample t test was performed in this case. Model parameters included global normalization, with proportional scaling and relative threshold masking at 80% of mean voxel value. Parameters were estimated and contrasts were generated to create statistical parametric maps of T values. The statistical threshold was set at p < 0.005 with an extent threshold of 100 contiguous voxels. Activated clusters were evaluated and anatomically located using an ROI template [27].

Results

PET studies and 3-D autoradiography

PET scans from a representative rat under conscious and anaesthetized conditions are shown in Fig. 3b and c, respectively, together with an MRI image (Fig. 3a). Widespread glucose hypometabolism can be seen when the animal was anaesthetized versus conscious during the period of 18F-FDG uptake.

Autoradiographic images were acquired, processed and successfully 3-D reconstructed using the described procedure. Visual inspection of axial slices showed continuity of the borders of internal structures, such as the thalamus and basal ganglia. Each 3-D-rendered surface also exhibited a consistent global shape of the whole-brain volume (Fig. 4). The procedure was therefore well designed and produced geometrically consistent volumes.

Figure 5 illustrates representative autoradiographic coronal brain slices of conscious (Fig. 5b) and isoflurane-anaesthetized animals (Fig. 5c). Under both conditions, glucose uptake was heterogeneously distributed according to regional differences in metabolic rate. As also noted with PET, a widespread decrease in glucose metabolism during anaesthesia was clearly observed in the cortex, with hypometabolism also being apparent in subcortical structures.

Statistical analysis of PET studies

The areas displaying significantly decreased metabolism in the anaesthetized versus the conscious condition are shown in Fig. 6. A statistical T map was overlaid on the canonical MRI [10] coronal slices. Volume of interest contours of some cortical areas and the thalamus were superimposed on these images to show the location of the activation, resulting in the illustrated 3-D volume-rendered image of the statistical T map.

An extensive cortical area showed significant differences with SPM analysis between the two acquisition conditions. SPM results are summarized in Table 1. One widespread cluster was detected, covering bilateral somatosensory cortex and other functional areas such as the auditory and visual cortices.

Statistical analysis of 3-D autoradiography

The results of the SPM analysis of the generated 3-D autoradiography are shown in Fig. 7. For visualization of the T score map, significant voxels were projected onto the 3-D-rendered high-resolution brain MRI scan, thus allowing anatomical identification. Based on a height threshold of p < 0.005, there was significant deactivation in extensive cortical areas and the thalamus of anaesthetized rats. Table 1 lists the activated clusters where significant differences were observed, together with the coordinates and significance level [Z and T scores and family-wise error (FWE)-corrected p] of the maximum peak and the areas covered by each cluster.

Discussion

In the present study, we explored the feasibility of using SPM for the analysis of 18F-FDG PET of the rat brain acquired in our MOSAIC Philips small animal PET. Voxel-based analysis is a widely applied technique in human studies and holds considerable promise for research using rodent models. Although several studies have performed SPM analysis in rats [28, 29], none of them has questioned the validity of the results taking into account the limitation in spatial resolution.

As our goal was to undertake a feasibility study, we chose the most widely used radiotracer, 18F-FDG, which measures glucose metabolism. The comparison selected was PET studies conducted in animals that were either conscious or maintained under isoflurane anaesthesia during the tracer uptake period, reflecting commonly encountered experimental protocols that have been reported to produce significantly different results. This issue has been investigated in several animal species [13, 22, 30], although, to the best of our knowledge, no study to date has based its analysis on statistical maps.

In order to validate the capacity of our tomograph combined with a voxel-based analysis to discriminate different conditions, results obtained from 18F-FDG PET studies were compared to the autoradiographic data acquired under the same physiological conditions, reconstructed as a 3-D volume and analysed using SPM. The use of a voxel-based technique to analyse PET images of rat brains would be validated if differences detected with 18F-FDG PET matched our autoradiography measurements, which were considered to represent the gold standard.

Very few studies have compared the performance of PET and autoradiography in rodent brains, but in all cases in which this has been attempted the analysis was based on manually drawn ROIs. Toyama et al. [13] reported a high correlation between regional cerebral glucose quantified with 18F-FDG PET and autoradiographic 2-14C-DG in normoglycaemic mice. Similarly, Mizuma et al. [30] found a clear correlation between regional uptake of 18F-FDG in mice measured by PET and ex vivo autoradiography. In another study, Strome et al. [14] reported a significant correlation between in vivo small animal PET images and in vitro autoradiography measurements of striatal 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) binding in the rat brain. However, none of these articles comparing PET and autoradiographic techniques performed voxel-based analysis. Therefore, the major novelty of this work is the validation of SPM analysis of rat brain PET by direct comparison to voxel-based analysis applied over high-resolution autoradiography.

Although the PET and autoradiography studies were carried out at different times, we rigorously applied the same protocols in relation to the animal’s condition. Given that autoradiography is a postmortem technique, each animal could only be studied under one condition, whereas both conditions were evaluated for each animal using PET. This difference required different statistical analysis, i.e. a paired t test for PET and an unpaired t test for autoradiography. The other crucial difference between autoradiography and PET is that the former is a 2-D technique whereas PET is a 3-D technique. However, this problem was solved with the construction of a 3-D volume from the autoradiographic slices. Although this procedure has already been reported in the literature, with high-quality results, the existing published images are mainly based on 14C autoradiography [17, 19], which yields better spatial resolution. Another noteworthy contribution of the present study is the demonstration that 3-D volume construction also works for PET radiotracers, with the advantage that the same tracer (18F-FDG) could be used for both techniques and a shorter film exposure was required for autoradiography (1 h vs several days).

The results obtained using SPM analysis of autoradiography revealed that rats anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane had dramatically lower 18F-FDG uptake in the cortex and the thalamus, compared with conscious animals, consistent with previous reports. Shimoji et al. [22] performed long-duration postmortem PET on only one rat per condition, conscious and under isoflurane anaesthesia during tracer uptake. Their images demonstrated visual heterogeneity between the grey matter and the white matter of the conscious rat, whereas the anaesthetized rat showed decreased activity and decreased heterogeneity in almost all regions. The same pattern was observed in our autoradiographic images, and similar results have also been published for mice. Mizuma et al. [30] quantitatively evaluated 18F-FDG PET results obtained under both conscious and anaesthetized (2% isoflurane) conditions in mice and demonstrated that anaesthesia lowered glucose consumption in the cerebral cortex, striatum and thalamus and, to a lesser extent, the cerebellum. We obtained similar results with regards to the cortex and thalamus, but did not observe any decrease in the striatum. We were also unable to analyse cerebellar uptake due to the fact that the autoradiographic slices at this level were of poor quality and therefore unsuitable for the 3-D volume construction. Consequently, we only analysed from the frontal association cortex (bregma 5.6 mm) to the vicinity of the inferior colliculus (bregma −8.0 mm). Another study [13] evaluated metabolic effects of anaesthesia in mice based on PET and autoradiography and found major quantitative differences in regional cerebral glucose utilization in the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital cortices. Both Mizuma et al. and Toyama et al. performed their analyses based on manually drawn ROIs.

Voxel-based analysis of our PET data revealed significantly decreased 18F-FDG metabolism in the anaesthetized versus conscious condition. This difference principally occurred in the sensorimotor cortex, reflecting the results obtained by autoradiography. However, autoradiography also revealed a significant deactivation in the thalamus that was not observed using PET. The reason for this may be the limited resolution of our PET tomograph which hindered analysis on a voxel basis. However, the volume of the rat brain is approximately 2 cm3 [31], meaning that even with the best dedicated PET tomograph with a spatial resolution of around 1.5 mm, the number of voxels inside the brain would be limited to a few hundred. Thus, the spatial resolution of current small animal PET systems imposes a major limitation for PET imaging studies of the rat brain. Despite this, the methodology still proved useful to highlight differences in the cortex, but was not sufficient to detect changes in deeper brain structures.

The limited resolution of our system produced partial volume effects, which means that the radioactive concentration of a structure spreads into the neighbouring tissues (spill-out), in addition to spread from these surrounding tissues into the structure under consideration (spill-in). These phenomena have been theoretically proven to prevent the correct quantification of 3-D spheres with diameters less than 2.7 times the resolution of the acquisition equipment, measured as the FWHM of the point spread function [32]. In this particular study, using the Philips MOSAIC small animal PET tomograph, accurate quantification of structures smaller than approximately 8 mm was not feasible, which is greater than the size of some structures in the rat brain. This fact can be observed visually over our PET images, in which it is almost impossible to differentiate inner structures. Although pixel-based partial volume correction could restore activity in small structures, and several algorithms have been developed to correct this effect in human brain imaging [33–35], they need to be optimized for their application in rodents.

Partial volume effect is especially important when using a nonspecific radiotracer such as 18F-FDG, which measures the metabolism of glucose, the metabolic substrate of most brain structures. However, when other tracers with spatially limited and specific uptake are used, it is possible to see and quantify the uptake in small regions such as the striatum [3, 36, 37]. In this case, analysis using ROIs or voxel-based techniques would be easier than with 18F-FDG, although accurate quantification would still be limited by partial volume effects.

Despite the limitations of the present study, SPM analysis of 18F-FDG PET acquired in our tomograph did prove useful for detecting major differences in extensive areas of the brain. It must be noted, however, that although a global decrease in cortical metabolism was apparent in our PET images, it was virtually impossible to anatomically localize the affected areas. Although the partial volume effect prevented detection of differences in smaller structures, SPM analysis of rat brain PET provides a good alternative to volume of interest analysis, particularly when taking into account that brain structures were visually indistinguishable over the PET image. The technique proposed in this paper can be useful to study several paradigms such as brain glucose metabolism in rat models of ischaemia or neurodegenerative diseases.

Conclusion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the feasibility of using 18F-FDG images of the rat brain acquired on a small animal PET tomograph that was not specifically designed for rodents in order to perform voxel-based analysis with SPM. Our results showed that regional differences identified by PET are in good agreement with those obtained using the standard reference technique, 3-D autoradiography, thereby confirming that any difference detected with PET actually exists. However, SPM analysis of 3-D autoradiography data also highlighted changes in other small areas not detected with PET. Based on these experiments, even using a tomograph with limited spatial resolution, SPM analysis of 18F-FDG PET of rat brain provides reliable results, although partial volume effects might make it difficult to detect slight differences in small regions. The procedures described in this study could also be applied to PET studies for other radiotracers and animal models.

References

Eidelberg D. Metabolic brain networks in neurodegenerative disorders: a functional imaging approach. Trends Neurosci 2009;32:548–57.

Blesa J, Juri C, Collantes M, Peñuelas I, Prieto E, Iglesias E, et al. Progression of dopaminergic depletion in a model of MPTP-induced Parkinsonism in non-human primates. An (18)F-DOPA and (11)C-DTBZ PET study. Neurobiol Dis 2010;38:456–63.

Casteels C, Lauwers E, Bormans G, Baekelandt V, Van Laere K. Metabolic-dopaminergic mapping of the 6-hydroxydopamine rat model for Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008;35:124–34.

Maeda J, Ji B, Irie T, Tomiyama T, Maruyama M, Okauchi T, et al. Longitudinal, quantitative assessment of amyloid, neuroinflammation, and anti-amyloid treatment in a living mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease enabled by positron emission tomography. J Neurosci 2007;27:10957–68.

Goffin K, Van Paesschen W, Dupont P, Van Laere K. Longitudinal microPET imaging of brain glucose metabolism in rat lithium-pilocarpine model of epilepsy. Exp Neurol 2009;217:205–9.

Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline J, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach. Hum Brain Mapp 1994;2:189–210.

Casteels C, Martinez E, Bormans G, Camon L, de Vera N, Baekelandt V, et al. Type 1 cannabinoid receptor mapping with [18F]MK-9470 PET in the rat brain after quinolinic acid lesion: a comparison to dopamine receptors and glucose metabolism. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010;37:2354–63.

Frumberg DB, Fernando MS, Lee DE, Biegon A, Schiffer WK. Metabolic and behavioral deficits following a routine surgical procedure in rats. Brain Res 2007;1144:209–18.

Casteels C, Vermaelen P, Nuyts J, Van Der Linden A, Baekelandt V, Mortelmans L, et al. Construction and evaluation of multitracer small-animal PET probabilistic atlases for voxel-based functional mapping of the rat brain. J Nucl Med 2006;47:1858–66.

Schweinhardt P, Fransson P, Olson L, Spenger C, Andersson JLR. A template for spatial normalisation of MR images of the rat brain. J Neurosci Methods 2003;129:105–13.

Schmidt KC, Smith CB. Resolution, sensitivity and precision with autoradiography and small animal positron emission tomography: implications for functional brain imaging in animal research. Nucl Med Biol 2005;32:719–25.

Nikolaus S, Larisch R, Beu M, Vosberg H, Müller-Gärtner HW. Imaging of striatal dopamine D(2) receptors with a PET system for small laboratory animals in comparison with storage phosphor autoradiography: a validation study with (18)F-(N-methyl)benperidol. J Nucl Med 2001;42:1691–6.

Toyama H, Ichise M, Liow JS, Modell KJ, Vines DC, Esaki T, et al. Absolute quantification of regional cerebral glucose utilization in mice by 18F-FDG small animal PET scanning and 2-14C-DG autoradiography. J Nucl Med 2004;45:1398–405.

Strome EM, Cepeda IL, Sossi V, Doudet DJ. Evaluation of the integrity of the dopamine system in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease: small animal positron emission tomography compared to behavioral assessment and autoradiography. Mol Imaging Biol 2006;8:292–9.

Wang JL, Oya S, Parhi AK, Lieberman BP, Ploessl K, Hou C, et al. In vivo studies of the SERT-selective [18F]FPBM and VMAT2-selective [18F]AV-133 radiotracers in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Nucl Med Biol 2010;37:479–86.

Ravasi L, Shimoji K, Soto-Montenegro ML, Esaki T, Seidel J, Sokoloff L, et al. Use of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose and the ATLAS small animal PET scanner to examine cerebral functional activation by whisker stimulation in unanesthetized rats. Nucl Med Commun 2011;32:336–42.

Nguyen P, Holschneider D, Maarek J, Yang J, Mandelkern M. Statistical parametric mapping applied to an autoradiographic study of cerebral activation during treadmill walking in rats. Neuroimage 2004;23:252–9.

Lee JS, Ahn SH, Lee DS, Oh SH, Kim CS, Jeong JM, et al. Voxel-based statistical analysis of cerebral glucose metabolism in the rat cortical deafness model by 3D reconstruction of brain from autoradiographic images. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005;32:696–701.

Dubois A, Dauguet J, Herard A, Besret L, Duchesnay E, Frouin V, et al. Automated three-dimensional analysis of histological and autoradiographic rat brain sections: application to an activation study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:1742–55.

Dubois A, Hérard A, Delatour B, Hantraye P, Bonvento G, Dhenain M, et al. Detection by voxel-wise statistical analysis of significant changes in regional cerebral glucose uptake in an APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 2010;51:586–98.

Nguyen PT, Selley DE, Sim-Selley LJ. Statistical Parametric Mapping reveals ligand and region-specific activation of G-proteins by CB1 receptors and non-CB1 sites in the 3D reconstructed mouse brain. Neuroimage 2010;52:1243–51.

Shimoji K, Ravasi L, Schmidt K, Soto-Montenegro ML, Esaki T, Seidel J, et al. Measurement of cerebral glucose metabolic rates in the anesthetized rat by dynamic scanning with 18F-FDG, the ATLAS small animal PET scanner, and arterial blood sampling. J Nucl Med 2004;45:665–72.

Huisman MC, Reder S, Weber AW, Ziegler SI, Schwaiger M. Performance evaluation of the Philips MOSAIC small animal PET scanner. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2007;34:532–40.

Collantes M, Prieto E, Peñuelas I, Blesa J, Juri C, Martí-Climent J, et al. New MRI, 18F-DOPA and 11C-(+)-α-dihydrotetrabenazine templates for Macaca fascicularis neuroimaging: advantages to improve PET quantification. Neuroimage 2009;47:533–9.

Surti S, Karp JS, Perkins AE, Cardi CA, Daube-Witherspoon ME, Kuhn A, et al. Imaging performance of A-PET: a small animal PET camera. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2005;24:844–52.

Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego, Elsevier; 2007.

Hooker JM, Patel V, Kothari S, Schiffer WK. Metabolic changes in the rodent brain after acute administration of salvinorin A. Mol Imaging Biol 2009;11:137–43.

Ahn SH, Oh SH, Lee JS, Jeong JM, Lim D, Lee DS, et al. Changes of 2-deoxyglucose uptake in the rat auditory pathway after bilateral ablation of the cochlea. Hear Res 2004;196:33–8.

Sung KK, Jang DP, Lee S, Kim M, Lee SY, Kim YB, et al. Neural responses in rat brain during acute immobilization stress: a [F-18]FDG micro PET imaging study. Neuroimage 2009;44:1074–80.

Mizuma H, Shukuri M, Hayashi T, Watanabe Y, Onoe H. Establishment of in vivo brain imaging method in conscious mice. J Nucl Med 2010;51:1068–75.

Kung MP, Kung HF. Mass effect of injected dose in small rodent imaging by SPECT and PET. Nucl Med Biol 2005;32:673–8.

Kessler RM, Ellis Jr JR, Eden M. Analysis of emission tomographic scan data: limitations imposed by resolution and background. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1984;8:514–22.

D’Ambrosio D, Marengo M, Boschi S, Fanti S,Spinelli AE. Post-reconstruction partial volume correction of PET images using iterative deconvolution algorithm and anatomical priors. IFMBE Proc 2010;25:257–60.

Rousset OG, Collins DL, Rahmim A, Wong DF. Design and implementation of an automated partial volume correction in PET: application to dopamine receptor quantification in the normal human striatum. J Nucl Med 2008;49:1097–106.

Tohka J, Reilhac A. Deconvolution-based partial volume correction in raclopride-PET and Monte Carlo comparison to MR-based method. Neuroimage 2008;39:1570–84.

Collantes M, Peñuelas I, Álvarez-Erviti L, Blesa J, Martí-Climent JM, Quincoces G, et al. Use of 11C-(+)-α-dihydrotetrabenazine for the assessment of dopaminergic innervation in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Rev Esp Med Nucl 2008;27:103–11.

Sossi V, Dinelle K, Topping GJ, Holden JE, Doudet D, Schulzer M, et al. Dopamine transporter relation to levodopa–derived synaptic dopamine in a rat model of Parkinson’s: an in vivo imaging study. J Neurochem 2009;109:85–92.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Margarita Ecay and Izaskun Bilbao for their excellent work in the animal preparation and acquisition of the PET studies, and also the cyclotron staff of the Nuclear Medicine Department of Clínica Universidad de Navarra for the radiotracer production.

The authors are also grateful to Ana Vegas and Rubén Fernández de la Rosa, from the FINNOVA program of the Community of Madrid for their assistance in the performance of the autoradiographic images, the Cyclotron Unit and Instituto Tecnológico PET (ITP).

This research was supported in part by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación grants SAF 2009–09020 and CENIT MIND. CJ is supported by the ALBAN Programme, the European Union Programme of High Level Scholarships for Latin America, scholarship No.E07D403507CL.

Dr. Michael Paterson kindly corrected and edited the article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prieto, E., Collantes, M., Delgado, M. et al. Statistical parametric maps of 18F-FDG PET and 3-D autoradiography in the rat brain: a cross-validation study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 38, 2228–2237 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-011-1905-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-011-1905-y