Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to assess the reproducibility in healthy volunteers of α-[11C]methyl-l-tryptophan (α[11C]MT) brain trapping imaging with positron emission tomography (PET), using volumes of interest (VOIs) and voxel-based image analysis.

Methods

Six right-handed healthy male volunteers (34.3±10.9 years) with a negative family history for psychiatric disorders were scanned twice in the resting condition, 22±17 days apart. An unbiased semiautomatic segmentation of the brain was used to define VOIs. The trapping constant K* (ml g−1 min−1) for α[11C]MT was calculated for the whole brain and seven brain regions using the graphical method for irreversible tracers. In addition, parametric maps of K* were obtained from dynamic scans using the same method. Comparison of test and retest K* functional images was performed using SPM99. Student’s paired t statistic was applied for comparisons of α[11C]MT brain trapping in a priori selected VOIs.

Results

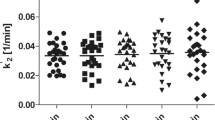

α[11C]MT brain trapping in VOIs showed a mean variability 2.6±1.8% (0.3–5%) for absolute and 1.5±2.1% (1.4–4.1%) for normalized K*. Intraclass correlations between test and retest conditions were 0.61±0.34 for absolute K* values and 0.73±0.20 for K* values normalized by global mean. SPM99 analysis using a height threshold of p=0.05 (two tailed) and an extent threshold of 100 voxels showed no significant differences between scans.

Conclusion

Rest measurements in healthy male volunteers of the trapping constant for α[11C]MT, using PET, appeared to be stable during an average interval of 3 weeks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The in vivo measurement of biochemical parameters of the serotonin (5-HT) system may reveal important aspects of 5-HT pharmacology in health and disease. Although several aspects of 5-HT neurotransmission have been described using positron emission tomography (PET) receptor ligand techniques, little information is available concerning in vivo 5-HT biosynthetic pathways. The aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) substrate [11C]-5-hydroxy-l-tryptophan was initially proposed as a probe for 5-HT synthesis [1]; however, among other limitations, this tracer lacks specificity for 5-HT fibers since the enzyme AAAD is present in all monoaminergic terminals [2]. Recently, a PET method designed to estimate 5-HT synthesis rate in vivo in the human brain, using the tracer α-[11C]methyl-l-tryptophan (α[11C]MT), has been developed [3, 4]. The method is based on in vivo measurements of the α[11C]MT plasma to brain trapping constant (K*, ml g−1 min−1) and, with some assumptions [5], provides a conversion into regional rates of brain 5-HT synthesis. αMT is a synthetic analog of the essential amino acid precursor of serotonin, L-tryptophan. Unlike L-tryptophan, αMT is not incorporated into protein [5]. Similarly to L-tryptophan, αMT crosses the blood–brain barrier, is taken up into serotonin neurons [6], and is metabolized into α-M-serotonin by tryptophan hydroxylase [7]; however, only a small fraction of the tracer will be metabolized during PET scan.

Hence, the assessment of time-dependent changes in brain serotonin synthesis, as a result of physiological and/or pharmacological interventions, is now deemed possible using repeated α[11C]MT/PET measurements . However, intraindividual variability in α[11C]MT brain trapping may hamper interpretation of such experiments, particularly when there are long interscan intervals. Indeed, several nonspecific factors are known to influence various aspects of serotonergic neurotransmission (i.e., tryptophan hydroxylase activity) across repeat measurements, including age, circadian and seasonal rhythms, diet, sleep, motor activity, and level of stress. Intraindividual variability in α[11C]MT brain trapping under rest conditions is not known.

The primary goal of the present study was to estimate the within-subject stability for the α[11C]MT brain trapping constant during repeat measurements carried out in healthy volunteers at an average interval of 3 weeks. The comparison of test and retest conditions was performed using automatically generated volumes of interest (VOIs) and statistical parametric mapping (SPM).

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [8] and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University. Six male, right-handed, healthy volunteers were selected via advertisements in a local newspaper. The study was restricted to one gender (male) because of recent reports of gender-related differences in α[11C]MT brain trapping [9]. All subjects were physically healthy and drug free, as determined by a physical examination and standard laboratory tests, together with urine drug screens obtained on the morning preceding each PET measurement (Biosite Diagnosis, San Diego, CA, USA). Personal and family history of psychopathology was assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Non-Patient Edition [10], the Hamilton Depression Rate Scale (HDRS), and the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies [11]. Exclusion criteria included a personal or first-degree relative history of psychiatric disorders, a Beck Depression Inventory score >10, and a urine drug screen positive for illicit drugs. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Imaging acquisition protocol

All subjects underwent two α[11C]MT brain PET studies, 22±17 days apart, under strictly identical conditions (dim light, open eyes, and ears unplugged); both scans were performed between 11:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m., using an ECAT EXACT HR+ PET camera (Siemens, CTI). Each α[11C]MT brain trapping measurement was preceded by a 24-h low protein diet in order to minimize intersubject variability of plasma concentrations of tryptophan and possibly other amino acids due to differences in diet. Each α[11C]MT dynamic PET acquisition had a duration of 60 min and was preceded by a 15-min 68Ga transmission scan. Dynamic acquisition was started concomitantly with the venous injection of 370 MBq (10 mCi; specific activity >500 Ci/μmol) of α[11C]MT, administered over a 2-min period. Images were acquired in the three-dimensional mode and reconstructed using filtered back-projection [Hanning filter, full-width at half-maximum (FWHM)=8 mm] with 24 frames, each with 128×128 voxels and 63 slices and a voxel size of 2.4×2×2 mm. During acquisition, 13 blood samples were drawn from the antecubital vein, at progressively longer time intervals, in order to provide plasma radioactive counts as well as plasma samples for the determination of concentrations of total and free tryptophan by means of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Input function was estimated from a combination of the brain venous sinus activity (first 20 min) and the venous plasma curve from 20 to 60 min [9].

All subjects underwent an MRI scan to provide an anatomical framework for VOIs and special normalization of α[11C]MT K* images. MRI was performed on a Philips Gyroscan 1.5-T superconducting magnet system (Philips Medical System, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). Images were collected using a three-dimensional volume acquisition, T1-weighted (3D fast field echo scan, TR=18 ms, TE=10 ms, flip angle=30°), over the whole brain. MRI data were stored in a 256×256×160 mm matrix with 1-mm cubic isotropic voxels.

Imaging analysis protocol and statistics

The α[11C]MT brain trapping constant (K*, ml g−1 min−1) was calculated using the arterial input graphical method for irreversible tracers [12], using dynamic data acquired between 20 and 60 min after the injection of α[11C]MT. The assumptions (and limitations) underlying this analysis and α[11C]MT kinetics are discussed in detail elsewhere [13–16]. K* was calculated at the voxel level, in VOIs and in the whole gray matter including subcortical structures (global K*). In VOIs the test–retest variability (Eq. 1), reliability (Eq. 2) [17], and coefficient of variation (Eq. 3) were defined as follows:

where MSBS and MSWS are the mean sum of squares between and within subjects, respectively, n is the number of within subject measurements, and μ K* and σK* refer to the mean and standard deviation of K* of VOIs.

α[11C]MT K* parametric images were generated following the method developed and validated by Okazawa and Diksic [18, 19], and analyzed voxel by voxel using SPM99. K* images were resampled to the International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) 2 mm isotropic stereotaxic space (spatial normalization) using a standard linear automatic algorithm [20]; subsequently these images were smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian filter to a final resolution of 14 mm FWHM, and normalized using proportional scaling in order to cancel out global effects on regional K* values. Voxelwise comparison of K* between scans 1 and 2 was performed using SPM99 [16], assuming a cut-off level of p<0.05 (height threshold), two tailed, and an extent threshold of 100 voxels [19, 21, 22].

Regional assessment of the stability of α[11C]MT was performed using 16 VOIs generated with an automatic algorithm. K* values were calculated using VOI time–activity curves obtained from dynamic PET scans resampled to the stereotaxic space. VOIs were determined on each subject’s MRI scan using an automatic segmentation method [23, 24] summarized in the Fig. 1. Briefly, individual MRI data were corrected for field inhomogeneities and resampled in a standard stereotaxic space [20, 25]. Subsequently, a tissue classification algorithm (INSECT) was used to classify MR images into gray and white matter and cerebrospinal fluid [26]. Finally, these data were submitted to Automatic Nonlinear Imaging Matching and Anatomical Labelling (ANIMAL) for segmentation into 16 anatomical volumes [20, 24]. All VOIs were visually inspected and errors corrected manually when necessary. PET dynamic scans were then resampled to MRI standard stereotaxic space, in order to calculate time–activity curves. K* values obtained with VOIs were compared using two-tailed paired t test with p<0.05 set as the level of significance (without multiple correction).

Summary of the automatic determination of VOIs using axial planes. Each individual MRI in native space (A1) was corrected for non-uniformities and resampled (A2) in the ICBM 305 1-mm stereotaxic space in order to be classified (A3) and segmented into VOIs (A4, A5). Seven VOIs were selected a priori and incorporated into an MRI volume (A5). Dynamic PET scans were resampled from the native (B1) to the standard ICBM 2-mm stereotaxic space (B2). Tissue radioactivity maps were obtained using individual anatomical VOIs applied to the dynamic PET scans

Results

Six male subjects aged 34.3±10.9 years (range 25–56 years) were selected for this study. Subjective mood scores and plasma concentrations of total and free tryptophan obtained during the two PET sessions did not differ between test and retest (Table 1). SPM99 comparison of K* functional images obtained during both PET measurements of α[11C]MT trapping showed no significant differences (Fig. 2). Likewise, VOI-based comparisons between test and retest conditions showed no significant difference for global (p=0.64) or regional absolute and normalized K* values for any of the selected VOIs (Tables 1, 2).

Overall, test–retest variability averaged about 3.8±1.2% (1–4.6%) for global absolute K* values and less than 1% for normalised K*. The average regional test–retest difference between the two measurements was 2.3±1.2 % (1.3–3.0%). Intraclass correlations between test and retest conditions were 0.61±0.34 for absolute K* values and 0.73±0.20 for normalized K* values. Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Discussion

In this study, the test–retest variability for α[11C]MT brain trapping in healthy male volunteers studied twice at an interval of 3 weeks averaged 2.6±1.8% for absolute and 1.55±2.1% for normalized regional K* values (Table 3). This is well within the range of the test–retest variability observed in studies with FDG [27] and amino acid PET tracers such as FDOPA [28], [11C]-5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan [1], and [11C]aminocyclohexanecarboxylate [29]; it is also within the range of values previously reported for α[11C]MT in anesthetized rhesus monkeys [30]. Furthermore, the variability observed in the present study is approximately one-third to one-half of that observed during repeat measurements carried out in psychiatric patients studied once at an index episode and once several weeks later, at the time of recovery and/or treatment (unpublished data).

All subjects were studied under controlled conditions, at rest, in a nonstressful environment, at approximately the same time of the day, under a standard diet, and after a good night of sleep; in this way it was ensured that none of these factors had a significant influence on α[11C]MT brain trapping [9]. Likewise, the reported variability in α[11C]MT brain trapping could not be accounted for solely by differences in free or total tryptophan plasma concentrations, since they did not differ significantly between the two PET measurements. It may be argued that part of the variability reported in this study could be accounted for by differences in cerebral blood flow between times 1 and 2; however, this interpretation is unlikely to explain the findings since (1) test–retest variability for CBF measurements usually exceeds the 10–15% range, and (2) the trapping of α[11C]MT is not flow dependent [5]. Finally, the variability in α[11C]MT brain trapping reported here applies only to male volunteers; since previous findings suggest that brain serotonergic function may differ between males and females, in particular with respect to the influence of nonspecific factors such as diet or stress, studies of test–retest variability probably also need to be conducted in healthy female volunteers. However, it is unlikely that test–retest measurements would be less stable in females than in males.

Overall, α[11C]MT brain trapping did not differ significantly between test and retest in any of the brain regions examined. However, mean change for α[11C]MT brain trapping varied considerably across VOIs; thus, while some cortical (frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cortices), limbic (cingulate cortex), and subcortical (striatum, thalamus) measurements were very stable across time, others varied by a margin of 5% or more (temporal cortex, precentral gyrus). Whether these regional differences in variability, though not statistically significant, reflect biological variability needs to be further examined in a larger sample. The reduced variability obtained after global normalization indicates that a global effect is present in this sample.

In conclusion, α[11C]MT brain trapping appears to be a stable and reproducible measure in healthy male volunteers studied at rest, ca. 3 weeks apart. The stability was consistent in both voxelwise and VOI comparisons. These conclusions, if replicated in female volunteers and confirmed in a larger sample, support the use of this method to assess dynamic changes in brain 5-HT metabolism, i.e., 5-HT synthesis, in response to therapeutic interventions.

References

Hagberg GE, Torstenson R, Marteinsdottir I, Fredrikson M, Langstrom B, Blomqvist G. Kinetic compartment modeling of [11C]-5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan for positron emission tomography assessment of serotonin synthesis in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2002;22:1352–66

Frazer A, Hensler J. Serotonin. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, et al., eds. Basic neurochemistry, 5th edn. Vol. 3. New York: Raven Press; 1995

Diksic M, Nagahiro S, Sourkes TL, Yamamoto YL. A new method to measure brain serotonin synthesis in vivo. I. Theory and basic data for a biological model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1990;10:1–12

Muzik O, Chugani DC, Chakraborty P, Mangner T, Chugani HT. Analysis of [C-11]alpha-methyl-tryptophan kinetics for the estimation of serotonin synthesis rate in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997;17:659–69

Diksic M, Young SN. Study of the brain serotonergic system with labeled alpha-methyl-L-tryptophan. J Neurochem 2001;78:1185–200

Cohen Z, Tsuiki K, Takada A, Beaudet A, Diksic M, Hamel E. In vivo-synthesized radioactively labelled alpha-methyl serotonin as a selective tracer for visualization of brain serotonin neurons. Synapse 1995;21:21–8

Missala K, Sourkes TL. Functional cerebral activity of an analogue of serotonin formed in situ. Neurochem Int 1988;12:209–14

WHO. Declaration of Helsinki: recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. In: 18th World Medical Assembly. Helsinki: World Medical Association; 1964

Nishizawa S, Leyton M, Okazawa H, Benkelfat C, Mzengeza S, Diksic M. Validation of a less-invasive method for measurement of serotonin synthesis rate with alpha-[11C]methyl-tryptophan. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998;18:1121–9

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, William JBW. Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders—patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1998

Nurnberger JI Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:849–59; discussion 863–864

Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1983;3:1–7

Diksic M, Tohyama Y, Takada A. Brain net unidirectional uptake of alpha-[14C]methyl-L-tryptophan (alpha-MTrp) and its correlation with regional serotonin synthesis, tryptophan incorporation into proteins, and permeability surface area products of tryptophan and alpha-MTrp. Neurochem Res 2000;25:1537–46

Chugani DC, Chugani HT. PET: mapping of serotonin synthesis. Adv Neurol 2000;83:165–71

Shoaf SE, Carson RE, Hommer D, Williams WA, Higley JD, Schmall B, et al. The suitability of [11C]-alpha-methyl-L-tryptophan as a tracer for serotonin synthesis: studies with dual administration of [11C] and [14C] labeled tracer. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000;20:244–52

Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline JB, Frith CD, Frackoviak RS. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach. Hum Brain Mapp 1995;2:189–210

Seibyl JP, Laruelle M, van Dyck CH, Wallace E, Baldwin RM, Zoghbi S, et al. Reproducibility of iodine-123-beta-CIT SPECT brain measurement of dopamine transporters. J Nucl Med 1996;37:222–8

Okazawa H, Diksic M. Image generation of serotonin synthesis rates using alpha-methyltryptophan and PET. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1998;22:777–85

Okazawa H, Leyton M, Benkelfat C, Mzengeza S, Diksic M. Statistical mapping analysis of serotonin synthesis images generated in healthy volunteers using positron-emission tomography and alpha-[11C]methyl-L-tryptophan. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2000;25:359–70

Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM, Evans AC. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1994;18:192–205

Okazawa H, Diksic M. Image generation of serotonin synthesis rates using alpha-methyltryptophan and PET. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1998;22 5:777–85

Leyton M, Okazawa H, Diksic M, Paris J, Rosa P, Mzengeza S, et al. Brain regional [11C]methyl-L-tryptophan trapping in impulsive subjects with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:775–82

Collins LG, Evans AC. Animal: validation and applications of non-linear registration-based segmentation. Int J Pattern Recogn Art Intell 1997;11:1271–94

Collins DL, Zijdenbos AP, Barré WFC, Evans AC. ANIMAL+INSECT: inproved cortical structure segmentation. In: Kuba A, Samal M, Todd-Pokropek A, eds. Proc. of the annual symposium on information processing in medical imaging. Vol. 1613. Springer, 1999;210–23

Sled JG, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans Med Imag 1998;17:87–97

Zijdenbos A, Forghani R, Evans A. Automatic quantification of MS lesions in 3D MRI brain data sets: validation of INSECT. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 1998

Maquet P, Dive D, Salmon E, von Frenckel R, Franck G. Reproducibility of cerebral glucose utilization measured by PET and the [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose method in resting, healthy human subjects. Eur J Nucl Med 1990;16:267–73

Melega WP, Raleigh MJ, Stout DB, DeSalles AA, Cherry SR, Blurton-Jones M, et al. Longitudinal behavioral and 6-[18F]fluoro-L-DOPA-PET assessment in MPTP-hemiparkinsonian monkeys. Exp Neurol 1996;141:318–29

Koeppe RA, Mangner T, Betz AL, Shulkin BL, Allen R, Kollros P, et al. Use of [11C]aminocyclohexanecarboxylate for the measurement of amino acid uptake and distribution volume in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1990;10:727–39

Shoaf SE, Carson R, Hommer D, Williams W, Higley JD, Schmall B, et al. Brain serotonin synthesis rates in rhesus monkeys determined by [11C]alpha-methyl-L-tryptophan and positron emission tomography compared to CSF 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid concentrations. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998;19:345–53

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by grants from the NIH, CIHR, and FRSQ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosa-Neto, P., Diksic, M., Leyton, M. et al. Stability of α-[11C]methyl-l-tryptophan brain trapping in healthy male volunteers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 32, 1199–1204 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-005-1829-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-005-1829-5