Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the clinical and imaging outcome of patients with symptomatic eosinophilic granuloma of the spine treated with CT-guided intralesional methylprednisolone injection after biopsy.

Materials and methods

Patients (n =19) with symptomatic solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the spine treated by CT-guided intralesional methylprednisolone injection were retrospectively studied. There were 12 males and seven females with a mean age of 17 years (range, 3–43 years). The mean follow-up was 6 years (median, 4 years; range, 0.5–19 years). Spinal location included the cervical (two patients), thoracic (seven patients), lumbar spine (eight patients), and the sacrum (two patients). Vertebra plana was observed in two patients. All patients had biopsies before treatment.

Results

Complete resolution of pain and healing of the lesion was observed in 17 patients (89.5%); none of these patients had recurrence at the latest examination. Reconstitution of the T1 and L1 vertebra plana was observed in both patients. Two patients initially diagnosed and treated for a solitary eosinophilic granuloma had constant pain after the procedure; in these patients, 6 and 12 months after the procedure, respectively, imaging showed multifocal disease and systemic therapy was administered. Complications related to the procedure were not observed. General anesthesia was administered in two patients because of intolerable pain during the procedure.

Conclusions

In view of the benign clinical course of eosinophilic granuloma, in patients with symptomatic lesions, CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection is a safe and effective outpatient treatment with a low complication rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eosinophilic granuloma, a form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, is the most benign form of a group of diseases characterized by clonal proliferation of Langerhans-type histiocytes [1, 2]. It accounts for less than 1% of bone tumors and primarily involves the skull, mandible, spine, ribs, and long bones. In 80% of the cases it affects children and adolescents [3]. The etiology is unclear; viruses such as the Epstein–Barr virus and the human herpes virus-6, as well as bacteria and genetic factors have been implicated [4, 5]. An immunological dysfunction including an increase of certain cytokines such as the interleukin-1 and interleukin-10 in affected patients has also been reported; familial occurrence is very rare [2, 5, 6].

Eosinophilic granuloma of the spine accounts for 6.5–25% of total bone cases [7–14]. The most common location is the thoracic spine followed by the lumbar and the cervical spine [7, 12, 15–18]. No particular predilection for race, age, or gender has been reported for eosinophilic granuloma of the spine [6]; however, 80% of cases occur in children younger than 10 years of age [9, 11, 18]. In addition, although eosinophilic granuloma is said to be more common in males [18], results for gender distribution between studies has been contradictory [18]. Clinical symptoms are often severe and depend on spinal location [11, 12, 18]. The most common include back or neck pain, tenderness to spinal palpation and restricted range of motion, or torticollis; spinal instability and neurological symptoms are uncommon [12, 13, 19–23].

The rarity and the variable clinical course of spinal eosinophilic granuloma have resulted in a lack of management and therapeutic guidelines or clear evidence that treatment affects the natural history of this entity [17, 24–28]. Many authors have reported that observation and immobilization is adequate for most patients [19, 24, 28]. However, in patients with symptomatic eosinophilic granuloma, treatment other than simple observation is recommended [8, 10, 12, 17–19, 24–27].

In this study, 19 patients with symptomatic eosinophilic granuloma of the spine treated effectively by computed tomography (CT) guided intralesional injection of methylprednisolone after biopsy are presented, and their clinical and imaging outcome is discussed.

Patients and methods

The medical files of 19 patients with eosinophilic granuloma of the spine treated by CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection from January 1991 to December 2007 were retrospectively studied. There were 12 male and seven female patients with a mean age of 17 years (range, 3–43 years). Spinal location included the cervical spine (two patients), the thoracic spine (seven patients), the lumbar spine (eight patients), and the sacrum (two patients) (Table 1). All patients had solitary lesions as diagnosed prior to treatment by a skeletal survey and imaging studies of the lesion including standard radiography, conventional and three-dimensional CT scan in all patients, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium penta-acetate contrast medium in 15 patients. The mean follow-up of the patients of this series was 6 years (median, 4 years; range, 0.5–19 years). All patients gave written informed consent to be included in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of the authors’ institution.

At the same time period of this study, a total of 31 consecutive patients with solitary osteolytic spinal lesions and the presumptive imaging diagnosis of solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the spine were referred or admitted to the authors’ institution, as it is considered a tertiary tumor center. Nineteen of these patients had solitary lesions causing significant symptoms; these patients had biopsy for histological diagnosis followed by CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection and were included in this study. The remaining 12 patients had solitary lesions causing minor symptoms and were treated with observation alone or another type of treatment by their referring physician that is not known; these patients did not have CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection and were not included in this study.

The presenting clinical symptoms were constant, medium, or severe back or neck pain in all patients, local pain or tenderness in ten patients, torticollis in three patients, and dysphagia in one patient (Table 1). Radiography and CT scan showed an osteolytic lesion with ill-defined, permeated or moth-eaten margins and less commonly rounded, lobulated, thin, well-defined sclerotic rim. Vertebra plana was observed in two patients at T1 and L1 vertebra (patients 3 and 12). Magnetic resonance imaging showed low to intermediate signal intensity lesions on T1-weighted and high signal intensity lesions (higher than fat) in T2-weighted images.

Seventeen procedures were performed under local anesthesia using 5–15 ml of 2% mepivacaine cloridate; two procedures (patients 3 and 18) were performed under general anesthesia because of intolerable pain. The skin was prepared according to normal aseptical procedure. Under CT guidance, the lesion was located using a standard biopsy trocar or the trocar of the Bone Biopsy System (BONOPTY, RADI Medical Device, Sweden). The anterior lateral approach or the posterior transpedicular approach was used depending on the location of the lesions; in all cases, the biopsy/injection tract was positioned in line with the surgical incision for resection in case that histology would prove a malignancy of the spinal lesion. A tissue sample was retrieved and frozen sections were examined. In all cases, frozen sections showed eosinophilic granuloma. Contrast medium injection to evaluate for intravascular position of the lesion or the needle was considered not necessary and was not performed in any of the patients of this series since all lesions were intraosseous. After analysis of the frozen-section biopsy, CT-guided intralesional injection of methylprednisolone acetate (Depo-Medrol, 40 mg/ml) was done through the needle of the Bone Biopsy System or through an 18G spinal needle inserted through the biopsy trocar. We aimed at the middle of the lesion; if the lesion involved half or less of the vertebral body, 40 mg of methylprednisolone acetate were injected (eight patients); if the lesion involved more than half of the vertebral body, 80 mg of methylprednisolone acetate was injected (11 patients). In all patients, one intralesional corticosteroid injection was performed. Definite histological examination of the biopsy specimens confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma. Postoperatively, a cervical spine soft collar was applied in two patients (patients 3 and 18) for 5 and 10 days, respectively.

Post-procedural evaluation was performed at 2 and 4 months and then annually, and at the latest examination for the purpose of this study. Routine follow-up clinical evaluation included the presence of pain and restriction of spinal range of motion. Follow-up, imaging evaluation was done with CT scan; MRI was performed only if pain was present. The clinical and imaging data were recorded for each patient.

Results

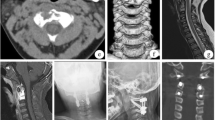

Complete resolution of pain and imaging healing of the lesion was observed in 17 patients (89.5%) (Figs. 1 and 2). Resolution of clinical symptoms was observed at 48–72 h after the procedure in 15 patients and in 7 days in two patients (patients 14 and 18); none of these patients had recurrence at the latest examination. Reconstitution of the T1 (patient 3) (Fig. 3) and L1 (patient 12) vertebra plana was observed in both patients. Two patients (patients 1 and 4) initially diagnosed and treated for a solitary eosinophilic granuloma did not respond to treatment and had continuous pain after the procedure; in these patients, 6 and 12 months after the procedure, respectively, imaging studies showed multifocal disease and systemic therapy was administered. One patient (patient 15) had low back and left leg pain at the latest evaluation. In this patient, L4-L5 degenerative disc disease and L5 spondylolisthesis was diagnosed. Another patient (patient 19) had upper extremity pain. In this patient, magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine showed bulging of the C5-C6 and C6-C7 intervertebral discs and cervical spondylosis; T2-weighted MRI showed signal intensity of a healed bone lesion similar to normal bone marrow.

a T1-weighted and b fat-suppression T2-weighted MRI of the cervical spine of a 43-year-old woman with pain, tenderness, and torticollis from a C7 lesion (patient 19). The lesion has low to intermediate signal intensity in T1-weighted and high signal intensity in T2-weigthed images. c Axial CT scan shows the osteolytic lesion at the vertebral body of C7. d Frozen-section biopsy showed eosinophilic granuloma and CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection was done. At 4 years, e T1-weighted, f fat-suppression T2-weighted MRI and g axial CT scan showed healing of the C7 lesion. The lesion has low-signal intensity in T2-weighted images

a T1-weighted and b T2-weighted MRI of the cervical spine of a 19-year-old woman with pain, tenderness, and torticollis from a C6 lesion (patient 18). The lesion is low to intermediate in T1 and hyper-intense in T2-weigthed images. c Axial CT scan shows the osteolytic lesion at the vertebral body of C6. d Frozen-section biopsy showed eosinophilic granuloma and CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection was done. e At 4 years after CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection, sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the cervical spine shows low-signal intensity of the C6 lesion

Complications related to the procedure were not observed. General anesthesia had to be administered in two patients (patients 3 and 18) during the procedure because of intolerable pain. These patients had to be admitted post-procedural for overnight medical evaluation and were discharged from the hospital the next day. All the remaining patients were discharged from the hospital the same day after the procedure.

Discussion

Case reports and small series have documented the role of direct intralesional corticosteroids injections for the treatment of patients with eosinophilic granuloma, showing a cure rate of up to 97% [29]. In the current study, a series of 19 patients with symptomatic eosinophilic granuloma of the spine was reviewed to evaluate treatment by CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection. At a mean follow-up of 6 years (median, 4 years), 17 patients (89.5%) had resolution of their lesions; in two patients that did not respond to treatment, multifocal disease was diagnosed at 6 and 12 months after treatment, respectively.

The present study did not compare with a group of patients that had observation alone or other type of treatment. In addition, the age of the patients varies widely. Eosinophilic granuloma of the spine in children is known to resolve spontaneously with time and treatment may not be recommended; these factors may be considered a limitation. However, in the present series, all patients had symptomatic lesions; in these patients, treatment other than simple observation or biopsy alone is required. We acknowledge that biopsy may have an effect on bone healing and lesion reconstitution [30]; this may also be considered a limitation since the results of this study cannot evaluate this effect because all patients had a biopsy. However, we believe that histological diagnosis is paramount for all bone lesions and disagree that patients, especially children with symptomatic bone lesions should be left alone and the disease take its natural course without a histological diagnosis. We recommend that these patients should undergo biopsy for histological diagnosis and then consider treatment; biopsy should not be considered as a strategy for treatment of eosinophilic granuloma [30] but rather as a step to confirm diagnosis. By using the technique presented herein, frozen-section histological diagnosis was obtained in all patients. After biopsy, intralesional injection of methylprednisolone was performed, which is considered beneficial [25, 27, 29], or at least not harmful. Even if the definite histological diagnosis was different, which was not the fact in any of the patients in this series, intralesional corticosteroid injection would not have resulted in any adverse effect, but rather it would have decreased intralesional edema and provided for pain relief. Theoretically, in case of infection, corticosteroid injection could worsen the disease. In line with the literature, a follow-up of at least 4 years is required for patients with eosinophilic granuloma [30, 31]. In the present study, the mean follow-up was 6 years (median, 4 years; range, 0.5–19 years); the long-term follow up in addition to the low incidence of this condition and the large sample size of our series increase the power of this study.

Diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma of the spine can be challenging. Imaging studies may reveal different degrees of vertebral involvement, ranging from isolated lytic lesions to a more significant vertebral collapse that involves pedicles and posterior vertebral elements (vertebra plana) [23], peridural spread, and paraspinal soft tissue components [18, 23]. Although eosinophilic granuloma is the most common cause of vertebra plana, this finding can also be found in Ewing’s sarcoma and other tumors, infections such as tuberculosis, and osteogenesis imperfecta [32, 33]. In favor of the eosinophilic granuloma are the isolated spinal disease, the lack of constitutional symptoms, and the minimal laboratory abnormalities [32]. In addition, cases of spinal eosinophilic granuloma without vertebra plana are also numerous [18, 23]; cervical spine eosinophilic granuloma more often manifests with osteolytic lesions, rather than vertebra plana [16, 18, 34]. Similar osteolytic lesions can result from plasmacytoma, multiple myeloma, osteochondritis, tuberculosis, or osteomyelitis [33]. Therefore, although in cases where typical clinical and imaging presentation tissue diagnosis may not be required [15, 16, 35], a biopsy is mandated to obtain accurate diagnosis when clinical and radiological manifestations are ambiguous [1, 13, 26]. As in the present series, CT-guided needle biopsy of spinal eosinophilic granulomas has been effective for histological diagnosis, with low morbidity and a diagnostic accuracy of 70–100% [13, 25, 27, 29, 31, 36].

A variety of treatments has been reported for solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the spine, including observation and immobilization [8, 10, 11, 26], intralesional corticosteroid injection, local excision and curettage with or without bone grafting, chemotherapy and irradiation, with a majority of satisfactory results and a recurrence rate of less than 20% [30, 31, 37, 38]. Generally, treatment of a typical vertebra plana with unique involvement of the vertebral body and absence of neurological deficit is conservative [14, 18, 23]. In patients with mild neurological deficits, immobilization and radiation has been reported [26]. Low-dose radiation is advocated by some authors to be effective in the healing of lytic lesions and limiting disease progression [22]; others argue that radiation may damage endochondral growth plates and limit vertebral reconstruction [24, 39] or lead to secondary morbidity from induced malignancy or myelitis [13, 40]. Although no clear correlation between the degree of vertebral collapse and the degree of neurological symptoms has been observed [23], in patients with severe pain and restriction of range of motion, and/or persistent spinal subluxation and neurological symptoms, surgical treatment is required [9, 10, 12, 17, 18]. Chemotherapy is not recommended for solitary lesions and should be reserved for systemic involvement [10, 18, 26] or as initial therapy in children with solitary eosinophilic granuloma in locations that preclude safe and complete surgical resection [41].

CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection, either as an adjunct to treatment or as primary treatment, as in the current series, has been reported safe and effective technique, with comparable results to other treatments [25, 27, 29]. Others reported that the administration of corticosteroids adds little in children [27, 30]. However, in patients with symptomatic lesions, as in the current series, treatment is required. In view of the usually benign clinical course of the disease, in these patients, a simple, minimally invasive, outpatient treatment with a low rate of complications such as CT-guided intralesional corticosteroid injection may be considered the treatment of choice. Depo-Medrol (40 mg/ml) was chosen because it is a microcrystalline suspension of acetate of methylprednisolone that is relatively insoluble and therefore has a prolonged pharmalogical effect [42]. Previous studies on the treatment of certain osteolytic lesions including bone cysts, aneurysmal cysts, eosinophilic granulomas, and nonossifying fibromas showed that the results obtained through the introduction of methylprednisolone acetate in crystals were better than those obtained by using other corticosteroids with topical action [42]. A particular dosage for eosinophilic granulomas of the spine cannot be recommended based on the results of the present series. The amount of methylprednisolone acetate injected was established empirically on the basis of the size of the vertebral lesion. A minimum of 40 mg for eight lesions involving less than half of the vertebral body and up to 80 mg for 11 lesions involving more than half of the vertebral body was injected. Some lesions may fail to respond or are unsuitable for treatment by injection because of their site, impending fracture, or soft-tissue invasion [27]. Although minimally invasive, complications such as obstructive hydrocephalus have been reported [27]. The ability of the involved vertebrae to reconstitute is believed to be due to the fact that the disease affects children before skeletal maturity so that the pubertal growth spurt provides sufficient time for adequate remodeling by the active growth plates that are spared by the disease process [13, 22, 31, 41]. Furthermore, it seems that incomplete vertebral remodeling usually does not lead to chronic pain or compromise structural integrity [1, 13, 22, 35].

In the present series, the practical experience of a single institution in a selected patient population has been described. All patients had frozen-section biopsy before the intralesional corticosteroid injection that was confirmed by the subsequent definite histological analysis of the biopsy specimens. Although this is not a controlled study, results of the present study support CT-guided intralesional methylprednisolone injection as a safe outpatient treatment for symptomatic eosinophilic granulomas of the spine with complete resolution of pain and imaging healing of the lesions.

References

Seimon LP. Eosinophil granuloma of the spine. J Pediatr Orthop. 1981;1:371–6.

Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee on Histiocytic/Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:157–66.

Puzzilli F, Mastronardi L, Farah JO, et al. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the calvaria. Tumori. 1998;84:712–6.

Glotzbecker MP, Carpentieri DF, Dormans JP. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. a primary viral infection of bone? Human herpes virus 6 latent protein detected in lymphocytes from tissue of children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:123–9.

Shimakage M, Sasagawa T, Kimura M, et al. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus in Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:862–8.

Hanapiah F, Yaacob H, Ghani KS, Hussin AS. Histiocytosis X: evidence for a genetic etiology. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1993;35:171–4.

Davidson RI, Shillito Jr J. Eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine in children. Pediatrics. 1970;45(5):746–52.

Sweasey TA, Dauser RC. Eosinophilic granuloma of the cervicothoracic junction. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:942–4.

Bilge T, Barut S, Yaymaci Y, Alatli C. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the lumbar spine in an adult. Case report. Paraplegia. 1995;33:485–7.

Scarpinati M, Artico M, Artizzu S. Spinal cord compression by eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 1995;18:209–12.

Brown CW, Jarvis JG, Letts M, Carpenter B. Treatment and outcome of vertebral Langerhans cell histiocytosis at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Can J Surg. 2005;48(3):230–6.

Tanaka N, Fujimoto Y, Okuda T, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the atlas. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(10):2313–7.

Greenlee JD, Fenoy AJ, Donovan KA, Menezes AH. Eosinophilic granuloma in the pediatric spine. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43(4):285–92.

Metellus P, Gana R, Fuentes S, et al. Spinal Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in a young adult: case report and therapeutic considerations. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21(2):228–30.

Robert H, Dubousset J, Miladi L. Histiocytosis X in the juvenile spine. Spine. 1987;12:167–72.

Sanchez RL, Llovet J, Moreno A, Galito E. Symptomatic eosinophilic granuloma of the spine: report of two cases and review of the literature. Orthopedics. 1984;7:1721–6.

Dickinson LD, Farhat SM. Eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1991;35:57–63.

Bertram C, Madert J, Eggers C. Eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. Spine. 2002;27:1408–13.

Kumar A. Eosinophilic granuloma of the spine with neurological deficit. Orthopedics. 1990;13:1310–2.

Villas C, Martínez-Peric R, Barrios RH, Beguiristain JL. Eosinophilic granuloma of the spine with and without vertebra plana: long-term follow-up of six cases. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6(3):260–8.

Maggi G, de Sanctis N, Aliberti F. Nunziata Rega A. Eosinophilic granuloma of C 4 causing spinal cord compression. Childs Nerv Syst. 1966;12(10):630–2.

Raab P, Hohmann F, Kuhl J, Krauspe R. Vertebral remodeling in eosinophilic granuloma of the spine: a long-term follow-up. Spine. 1998;23:1351–4.

Yeom JS, Lee CK, Shin HY, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the spine. Analysis of twenty-three cases. Spine. 1999;24:1740–9.

Nesbit ME, Kieffer S, D’Angio GJ. Reconstitution of vertebral height in histiocytosis X: a long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:1360–8.

Capanna R, Springfield DS, Ruggieri P, et al. Direct cortisone injection in eosinophilic granuloma of bone: a preliminary report on 11 patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5:339–42.

Osenbach RK, Youngblood LA, Menezes AH. Atlanto-axial instability secondary to solitary eosinophilic granuloma of C2 in a 12-year-old girl. J Spinal Disord. 1990;3:408–12.

Egeler RM, Thompson RC, Voute PA, Nesbit ME. Intralesional infiltration of corticosteroids in localized Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:811–4.

Beckstead JH, Wood GS, Turner RR. Histiocytosis X cells and Langerhans cells: enzyme histochemical and immunologic similarities. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:826–33.

Yasko AW, Fanning CV, Ayala AG, et al. Percutaneous techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of localized Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma of bone). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:219–28.

Plasschaert F, Craig C, Bell R, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma. A different behaviour in children than in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(6):870–2.

Sessa S, Sommelet D, Lascombes P, Prevot J. Treatment of Langerhans-cell histiocytosis in children. Experience at the Children’s Hospital of Nancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1513–25.

O’Donnell J, Brown L, Herkowitz H. Vertebra plana-like lesions in children: case report with special emphasis on the differential diagnosis and indications for biopsy. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:480–5.

Ferguson L, Shapiro CM. Eosinophilic granuloma of the second cervical vertebra. Surg Neurol. 1979;11:435–7.

Floman Y, Bar-On E, Mosheiff R, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the spine. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1997;6(4):260–5.

Ippolito E, Farsetti P, Tudisco C. Vertebra plana: long-term follow-up in five patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1364–8.

Elsheikh T, Silverman JF, Wakely Jr PE, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma) of bone in children. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7(3):261–6.

Ladisch S, Gadner H. Treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: evolution and current approaches. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1994;23:S41–6.

Geevasinga N, Jeremy R, Crombie CM, Manolios N. Histiocytosis and bone: experience from one major Sydney teaching hospital. Int Med J. 2005;35:622–5.

Green NE, Robertson Jr WW, Kilroy AW. Eosinophilic granuloma of the spine with associated neural deficit: report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:1198–202.

Johansson L, Larsson LG, Damber L. A cohort study with regard to the risk of haematological malignancies in patients treated with X-rays for benign lesions in the locomotor system. II. Estimation of absorbed dose in the red bone marrow. Acta Oncol. 1995;34:721–6.

Levy EI, Scarrow A, Hamilton RC, et al. Medical management of eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;31(3):159–62.

Scaglietti O, Marchetti PG, Bartolozzi P. The effects of methylprednisolone acetate in the treatment of bone cysts. Results of three years follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61:200–4.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rimondi, E., Mavrogenis, A.F., Rossi, G. et al. CT-guided corticosteroid injection for solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the spine. Skeletal Radiol 40, 757–764 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-010-1045-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-010-1045-7