Abstract

The pathogenesis of intraneural ganglia remains controversial. Only half of the reported cases of the most common type, the peroneal nerve at the fibular neck, have been found to have pedicles connecting the cysts to neighboring joints detected with preoperative imaging or intraoperatively. We believe that all intraneural ganglia arise from joints, and that radiologists and surgeons need to look closely preoperatively and intraoperatively for connections. Not identifying these connections with imaging and surgical exploration has led not only to skepticism about an articular origin of the cyst, but also to a high recurrence rate after surgery. We present a patient who had two recurrences of a peroneal intraneural ganglion in whom a joint connection was not detected on previous MRIs and operations. Reinterpretation of the original films and high-resolution MRI demonstrated an “occult” joint connection to the superior tibiofibular joint. MR arthrography performed after exercise and 1 h delay, however, clearly showed the connection and communication. The joint connection was then confirmed at surgery through an articular branch. Postoperatively the patient regained nearly normal neurologic function, and follow-up MRI showed no cyst recurrence. MR arthrography with delayed imaging should be considered in cases of intraneural ganglia when a joint connection is not obvious on MRI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

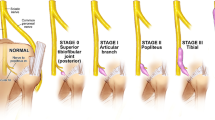

Intraneural ganglia are benign cysts that occur within the epineurium of nerves. They have been considered curious clinical entities because of their poorly understood pathogenesis. Various theories have been proposed, the most popular of which include a degenerative one in which cysts occur de novo due to degeneration of surrounding elements; and a synovial (articular) one in which cysts form directly from their joint relationship [1]. Lack of identification of a joint connection in approximately 50% of cases with imaging or surgery “supports” the degenerative theory and “disproves” the synovial theory[2]. While identification of a joint connection by itself lends support to the synovial theory, demonstration of a joint communication proves the synovial theory.

Recent evidence has shown a strong association of intraneural ganglia and joint connections if they are carefully looked for [3, 4]. Elucidating the pathogenesis of these cysts is necessary for us to understand this clinical entity but also to improve outcomes.[1] Not identifying and treating a joint connection risks recurrence after surgery. Ironically, joint connections are often identified after recurrences; in these cases, retrospective review of the initial images can typically reveal the connections.

Increased awareness and improved imaging can improve the preoperative evaluation and reveal a joint connection, even when it is not obvious. We present a case of a peroneal intraneural ganglion that had an “occult” connection to the superior tibiofibular joint which was not identified on two previous MRIs and at two operations. High-resolution MR arthrography performed with delayed imaging and after exercise documented a connection and communication, which helped guide surgeons to perform successful surgery.

Case Report

A 40-year-old man presented in December 2003 with a several-year history of a left foot drop due to a recurrent peroneal intraneural ganglion cyst despite two operations (Fig. 1). Prior imaging and surgical exploration specifically did not reveal any evidence of a joint connection. The patient also had a long history of injuries to his left lower limb. He sustained a left anterior cruciate ligament rupture and a medial meniscal tear in 1982, following a soccer injury, and had undergone open partial meniscectomy at that time. He had also suffered several left-sided ankle sprains in the past.

In September 2002, the patient began experiencing some discomfort in the leg and dorsum of his foot. Rather precipitously he developed severe pain, accompanied by a foot drop, in February 2003 after skiing. Physical examination revealed a dense deep peroneal nerve lesion affecting tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus and extensor hallucis longus. Peronei function was preserved. Decreased sensation was noted in the first dorsal web space only. MRI at that time revealed an intraneural ganglion cyst extending along the course of the peroneal nerve over a 7.5 cm segment (Fig. 2). There were also degenerative changes in the superior tibiofibular joint, and tricompartmental knee arthritis. There was full-thickness cartilage loss in the medial compartment with reactive subchondral edema, tearing of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus from the posterior tibial attachment and a 4-mm calcified loose body in the anterolateral recess of the knee joint. Postoperative changes from the medial meniscectomy were noted, as was a chronic complete proximal tear of the anterior cruciate ligament. A small knee effusion was present. No denervational changes were noted. That same month, decompression of the cyst was performed.

Initial preoperative MRI (February 2003). a Sagittal FSE T2 (TR=3750/40.6 ms) image with fat saturation shows cyst extending from the superior tibiofibular joint (arrow) down (dashed arrow) into the articular branch (arrowhead). b Sagittal FSE T2 (TR=3750/TE=40.6 ms) image with fat saturation shows fluid in the joint (arrow), along the course of the articular branch (arrowhead) and into (dashed arrow) the deep and common peroneal nerves (*). Note the prominent knee effusion (+). c and d Serial axial FSE T2 (TR=3,750/TE=39.2 ms) image with fat saturation shows cyst in superior tibiofibular joint (arrow), articular branch (arrowhead) and common peroneal nerve (*) in c. In d, the course of the articular branch of the peroneal nerve is shown better (arrowhead)

Over the next several months, the patient regained some function in his left foot, although he still had mildly-reduced foot dorsiflexion and moderate loss of toe extension, with persistent sensory loss in the great toe. In late September 2003, he felt a mass behind his knee, and developed dysesthesias in the foot. Ultrasound showed recurrence of the intraneural cyst (maximal dimensions 1.5×3.2×1.4 cm). That same week, he underwent microsurgical neurolysis and “complete” resection of the cyst from within the peroneal nerve at the level of the fibular head, maintaining the integrity of fascicles. Distally, normal nerve branches were seen. The histological appearances confirmed an intraneural ganglion cyst.

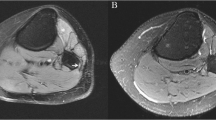

Immediately after the second surgery, he regained some additional motor strength and sensation, with only mild to moderate residual functional deficit. Three months later, however, he began experiencing similar prodromal symptoms of painful dysesthesias in the foot. Repeat ultrasound showed a 1.4×0.7×1.1 cm cyst in the same location. MRI confirmed the recurrence of a peroneal intraneural cyst at the level of the fibular neck region, which extended 3.5 cm proximally. No communication with the superior tibiofibular joint was noted by an experienced musculoskeletal radiologist (Fig. 3).

Postoperative MR images with recurrent peroneal intraneural cyst (December 2003). a Axial FSE T2 (TR=5100/TE=39.2 ms) image with fat saturation shows the intraneural cyst within the common peroneal nerve (*). There is cyst fluid in the superior tibiofibular joint (arrow) suggesting an occult connection not visualized in this image and the articular branch (arrowhead). b Axial FSE T2 (TR=5,100/TE=39.2 ms) image with fat saturation shows the cyst fluid tracking from the superior tibiofibular joint (arrow) along the course of the articular branch (arrowhead) and into the peroneal nerve (*). c Sagittal FSE T2 (TR=3516/TE=40.6 ms) image with fat saturation shows the cyst in the common peroneal nerve (*). There is fluid extending from the superior tibiofibular joint (arrow) along a portion of the articular branch (dashed arrow). Note the large knee effusion (+)

At the end of December 2003, the patient was referred to our institution for surgical intervention. Percussion over and proximal to the visible mass (Fig. 1) produced paresthesias in the dorsomedial aspect of the foot. Tibialis anterior was 3+/5; extensor digitorum longus and extensor hallucis longus 2/5; and peronei 5/5. Sensation was absent in the first dorsal web space, but was preserved in the dorsum of the foot. He was unable to walk on his heels. He had varus deformity of his knee with changes of moderate degenerative joint disease. He had full range of knee motion. Retrospective review of the previous MRI’s (Figs. 2 and 3) and ultrasounds (not shown) performed and interpreted elsewhere showed a characteristic “tail” sign connection to the superior tibiofibular joint.

To confirm joint communication, an MR arthrogram was performed (Fig. 4). Thirty cc of 1:200 dilute gadolinium in normal saline with 0.2 cc of 1:10,000 epinephrine were injected into the knee joint. Post contrast T1-weighted images with fat saturation were obtained in all three planes in addition to T2-weighted images with and without fat suppression. Initial images showed contrast within the knee and superior tibiofibular joint. The initial images demonstrated fluid but not contrast within the cyst. Delayed images were then performed 1 h later and immediately following multiple knee squats. MR images showed contrast material extending into the superior tibiofibular joint, around the neck of the fibula and then into the complex cyst. These images were reformatted using three-dimensional techniques to illustrate the communication of the knee joint and the superior tibiofibular joint with the peroneal intraneural ganglion after gadolinium administration (Fig. 5).

MR arthrography was performed in order to document joint communication. (December 2003) a T1-weighted (TR=566/TE=18 ms) image with fat saturation with intraarticular gadolinium shows extensive degeneration in knee and superior tibiofibular joint. There is no contrast within CPN. b T1-weighted (TR=566/TE=18 ms) image with fat saturation with intraarticular gadolinium shows small amount of contrast seen in superior tibiofibular joint (arrow). Initially, there is no contrast within the intraneural cyst. c FSE T2-weighted (TR=3,000/TE=68 ms) image with fat saturation at the same level as in a shows the peroneal intraneural cyst (*) and fluid in the superior tibiofibular joint. d FSE T2-weighted (TR=3,000/TE=68 ms) image with fat saturation at the same level as b shows fluid in the superior tibiofibular joint (arrow). Cyst fluid, seen along the course of the articular branch (arrowhead) of this image, is not visualized in the T1-weighted image (b), as this is not yet opacified with gadolinium. e Delayed oblique coronal T1-weighted (TR=700/TE=17 ms) image with fat saturation 1 h after exercise now shows opacification of the articular branch (closed arrowhead), confirming the connection to the superior tibiofibular joint (small arrow). There is a small amount of contrast in the common peroneal nerve (open arrowhead). Also, one can see the connection of knee and superior tibiofibular joint (open arrow)

Three-dimensional reconstructed image (post gadolinium administration) shows the communications between the knee joint, the superior tibiofibular joint and the course of the cyst (yellow) within the articular branch and into the common peroneal nerve itself. The common peroneal nerve and its articular, deep and superficial branches are depicted in green

Repeat surgery was performed. An intraneural ganglion involving the common peroneal nerve was identified proximal to the fibular neck region (Fig. 6). The cyst extended to a point 2 cm proximal to the peroneal tunnel region. There the common peroneal nerve appeared normal on its external surface. The dissection continued more distally into a previously unoperated region. The terminal branches were identified beneath the peroneus longus. The small articular branch was identified and traced to the superior tibiofibular joint, where the nerve branch had a cystic enlargement near its capsular insertion. The joint was opened up and cyst fluid was evacuated. The articular branch was ligated and disconnected from the joint. The articular branch appeared hollow with displaced fascicles. The superior tibiofibular joint was resected. A small longitudinal incision was made in the cystic region of the common peroneal nerve between fascicles (Fig. 6). Thick gelatinous material was evacuated from the nerve. Intraneural dissection was not performed and the cyst wall itself was not resected. Pathology confirmed an intraneural ganglion within the distal articular branch specimen.

Operative findings. a The intraneural cyst is seen within the common peroneal nerve (on background). The articular branch (red vasoloop within square box) appears normal on its exterior surface. Distally, the deep and superficial branches are within blue vasoloops. b The articular branch (red loop) extension of the cyst (*) has been traced to the superior tibiofibular joint (black spatula). c The articular branch itself seen in a above was ligated. Its distal most connection is shown. It appears hollow. This branch serves as a conduit between the superior tibiofibular joint and the cyst. The fascicles are displaced eccentrically. d The cyst is being incised longitudinally without disruption of individual fascicles. The superior tibiofibular joint (arrow) has been resected. e Gelatinous material is expressed from within the cyst. f The cyst wall is decompressed but not resected

Postoperatively the patient regained nearly complete function in the tibialis anterior and toe extensors over 6 months, and in the extensor hallucis longus by 15 months. He resumed his athletic lifestyle without limitations. MRI done 10 months postoperatively documented no recurrence of the cyst (Fig. 7).

Postoperative MR images after successful surgery (October 2004). a Axial T2-weighted FSE (TR=4,200/TE=38.5 ms) image with fat saturation shows postoperative changes of resection of superior tibiofibular joint without evidence of recurrent cyst. Some minor signal changes remain in the anterior compartment musculature. b T2-weighted (TR=600 ms/TE=12.5 ms) gradient echo image with fat saturation shows degenerative changes in the lateral compartment of the knee. The postoperative changes at the superior tibiofibular joint are exaggerated by the gradient echo technique. No recurrent or residual cyst is seen

Discussion

This case is consistent with the unified synovial theory that we have proposed for intraneural ganglia [1]. We believe that intraneural ganglia derive from joints, penetrate through a capsular rent, and dissect via the path of least resistance up the epineurium of nerves via articular branches. Increased intraarticular pressure increases the likelihood of cyst dissection through a one-way valve. By understanding the pathophysiology of these cysts, we feel that MRI techniques need to be exploited in order to best reveal these joint connections, especially when the latter appear not to exist.

This case also illustrates how easy it is for radiologists and surgeons to refute the synovial theory when an articular connection is not immediately obvious. In this particular case, the joint connection was not identified on routine imaging studies performed by experienced radiologists at other institutions (Figs. 2 and 3). While the joint connection was not immediately apparent, subtle suggestions of a connection could be established on our retrospective review of the MRIs and ultrasound studies. Surgeons on two occasions did not dissect distally enough to examine the articular branch sufficiently.

Various imaging modalities have been used to diagnose intraneural ganglia and establish a joint connection, including ultrasound [5–8], CT [9–12], and MRI [3, 13–15], routine arthrography and CT-arthrography have been used successfully in revealing joint communications with neighboring joints and intraneural ganglia [1, 16–21]. We believe that MR arthrography is the procedure of choice to reveal “occult” joint connections and communications in cases of intraneural ganglia. Similar to Malghem’s experience with CT-arthrography, first-pass imaging frequently does not reveal a joint communication. Delayed imaging seems to be beneficial in allowing contrast extravasation from the joint into para-articular cysts [22]. As observed by Hunt et al. [23] in a patient with an adventitial cyst of the popliteal artery that communicated with the knee joint, exercise also had an important effect, presumably by increasing intraarticular pressure. Because the visualization of the contrast medium within the cyst was relatively faint and the connection not easily visualized using standard imaging planes, three-dimensional imaging helped visualize the joint communication [24].

More experience is needed with MR arthrography and intraneural ganglia and the effects of varying time delays and amounts of exercise. One potential limitation of MR arthrography for peroneal intraneural ganglia is related to the difficulty in injecting the superior tibiofibular joint itself. Whilst injecting this joint can be accomplished with image guidance [25], injection of the knee joint is simpler and faster to perform, whenever this is feasible. The knee joint and the superior tibiofibular joints may only communicate with each other in 64% of cases [26]. Despite these data, we [1], like Malghem [19–21], have injected the knee and performed CT arthrography to delineate superior tibiofibular joint cysts. We wonder if a communication between the knee joint and the superior tibiofibular joint exists in a higher percentage of people than reported, or if patients with peroneal intraneural ganglia have a higher percentage of these communications. In fact, the communication between the knee joint and the superior tibiofibular joint may play a part in the underlying pathoanatomy; the patient in this paper, along with several others in our large series of peroneal intraneural ganglia [3], had knee effusions, which may contribute to distribution of higher intraarticular pressures.

Just as MR arthrographic techniques have proven to be the most sensitive technique for establishing joint communications with extraneural ganglia at other sites [27–31], we believe that this imaging modality can be applied to intraneural ganglia occurring elsewhere as well. We recently established a communication between the glenohumeral joint via a posterior labral tear in a patient with a recurrent suprascapular intraneural ganglion [32]. We believe that MR arthrography can be incorporated into a diagnostic algorithm to document joint communications when MRI or other imaging modalities do not adequately reveal joint connections.

Abbreviations

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- CT:

-

computerized tomography

- FSE:

-

fast spin echo

References

Spinner RJ, Atkinson JLD, Tiel RL. Peroneal intraneural ganglia: the importance of the articular branch. A unifying theory. J Neurosurg 2003;99:330–343

Spinner RJ. Lettre à redaction. Rev Chir Orthop 2005;91:492–494

Spinner RJ, Atkinson JLD, Scheithauer BW et al. Peroneal intraneural ganglia: the importance of the articular branch. Clinical series. J Neurosurg 2003;99:319–329

Rezzouk J, Durandeau A. Nerve compression by mucoid pseudocysts: arguments favoring an articular cause in 23 patients. Rev Chir Orthop 2004;90:143–146

Dubuisson AS, Stevenaert A. Recurrent ganglion cyst of the peroneal nerve: radiological and operative observations. Case report. J Neurosurg 1996;84:280–283

Lang CJG, Neubauer U, Qaiyumi S, Fahlbusch R. Intraneural ganglion of the sciatic nerve: detection by ultrasound. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 1994;57:870–871

Leijten FSS, Arts WF, Puylaert JBCM. Ultrasound diagnosis of an intraneural ganglion cyst of the peroneal nerve. Case report. J Neurosurg 1992;76:538–540

Prevot J, Goudot B, Aymard B, Gagneux E. Pseudo-kyste mucoide des nerfs peripheriques. A propos d’un cas opere. Chir Pediatr 1990;31: 181–184

Antonini G, Bastinanello S, Nucci F et al. Ganglion of deep peroneal nerve: electrophysiology and CT scan in the diagnosis. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1991;31:9–13

Firooznia H, Golimu C, Rafii M, Chapnick J. Computerized tomography in diagnosis of compression of the common peroneal nerve by ganglion cysts. Comput Radiol 1983;7:343–345

Gambari PI, Giuliania G, Poppi M, Pozzati E. Ganglionic cysts of the peroneal nerve at the knee: CT and surgical correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1990;14:801–803

Pazzaglia UE, Pedrotti L, Finardi E. Kyste synovial intranerveux du nerf sciatique poplite exeterne. Acta Orthop Belg 1989;55:253–256

Coakley FV, Finlay DB, Harper WM, Allen MJ. Direct and indirect MRI findings in ganglion cysts of the common peroneal nerve. Clin Radiol 1995;50:168–169

Leon J, Marano G. MRI of peroneal nerve entrapment due to a ganglion cyst. Magn Reson Imaging 1987;5:307–309

Uetani M, Hashmi R, Hayashi K, Nagatani Y, Narabayashi Y, Imamura K. Peripheral nerve intraneural ganglion cyst: MR findings in three cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1998;22:629–632

Godin V, Huaux JP, Knoops PH, Noël H, Rombouts JJ, Stasse P. Une cause rare de paralysie des muscle releveurs du pied: le kyste synovial intraneural du nerf sciatique poplite externe. Louvain Med 1985;104:281–286

Huaux JP, Malghem J, Maldague B, et al. La pathologie de l’articulartion peroneo-tibiale superiere. Histoires de kystes. A propos de quatre observations. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 1986;53:723–726

Lagarrigue J, Robert R, Resche F, Sindou M, Lazzerini P. Kystes synoviaux intranerveux du sciatique poplite externe. Neurochirurgie 1982;28:131–134

Malghem J, Vande Berg B, Lecouvet F, Lebon CH, Maldeague B. Atypical ganglion cysts. JBR-BTR 2002;85:34–42

Malghem J, Vande Berg BC, Lebon C, Lecouvet FE, Maldague BE. Ganglion cysts of the knee : articular communication revealed by delayed radiography and CT after arthrography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;170:1579–1583

Malghem J, Lecouvet FE, Vande Berg BC, Lebon CH, Maldague BE. Intraneural mucoid pseudocysts: a report of ten cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003;85:776–777

De Maesseneer M, De Boeck H, Shahabpour M, Hoorens A, Oosterlinck D, Van Tiggelen R. Subperiosteal ganglion cyst of the tibia. A communication with the knee demonstrated by delayed arthrography. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1999;81:643–646

Hunt BP, Harrington MG, Goode JJ, Galloway JM. Cystic adventitial disease of the popliteal artery. Br J Surg 1980;67:811–812

Spinner RJ, Edwards PK, Amrami KK. The application of three-dimensional rendering to joint-related ganglia. Clin Anat 2005;18:641

De Schrijver F, Simon JP, De Smet L, Fabry G. Ganglia of the superior tibiofibular joint: report of three cases and review of the literature. Acta Orthop Belg 1998;64:233–241

Bozkurt M, Yilmaz E, Atlihan D, Tekdemir I, Havitcioglu H, Gunal I. The proximal tibiofibular joint: an anatomic study. Clin Orthop 2003;406:136–140

Chandnani VP, Yeager TD, DeBerardino T et al. Glenoid labral tears: prospective evaluation with MR imaging, MR arthrography, and CT arthrography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;161:1229–1235

Lektrakul N, Chung CB, Lai Y-M et al. Tarsal sinus: arthrographic, MR imaging, MR arthrographic, and pathologic findings in cadavers and in cadavers and retrospective study data in patients with sinus tarsi syndrome. Radiology 2001;219:802–810

Magee T, Williams D, Mani N. Shoulder MR arthrography: which patient group benefits most? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:969–974

Tirman PF, Feller JF, Janzen DL, Peterfy CG, Bergman AG. Association of glenoid labral cysts with labral tears and glenohumeral instability: radiologic findings and clinical significance. Radiology 1994;190:653–658

Waldt S, Burkart A, Lange P, Imhoff AB, Rummeny EF, Woertler K. Diagnostic performance of MR arthrography in the assessment of superior labral anteroposterior lesions of the shoulder. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;182:1271–1278

Spinner RJ, Amrami KK, Kliot M, Johnson SP, Casañas J. Suprascapular intraneural ganglia and glenohumeral joint connections. J Neurosurg 2006 (in press)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spinner, R.J., Amrami, K.K. & Rock, M.G. The use of MR arthrography to document an occult joint communication in a recurrent peroneal intraneural ganglion. Skeletal Radiol 35, 172–179 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-005-0036-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-005-0036-6