Abstract

Introduction

Tinnitus is hypothesized to be an auditory phantom phenomenon resulting from spontaneous neuronal activity somewhere along the auditory pathway. We performed fMRI of the entire auditory pathway, including the inferior colliculus (IC), the medial geniculate body (MGB) and the auditory cortex (AC), in 42 patients with tinnitus and 10 healthy volunteers to assess lateralization of fMRI activation.

Methods

Subjects were scanned on a 3T MRI scanner. A T2*-weighted EPI silent gap sequence was used during the stimulation paradigm, which consisted of a blocked design of 12 epochs in which music presented binaurally through headphones, which was switched on and off for periods of 50 s. Using SPM2 software, single subject and group statistical parametric maps were calculated. Lateralization of activation was assessed qualitatively and quantitatively.

Results

Tinnitus was lateralized in 35 patients (83%, 13 right-sided and 22 left-sided). Significant signal change (P corrected < 0.05) was found bilaterally in the primary and secondary AC, the IC and the MGB. Signal change was symmetrical in patients with bilateral tinnitus. In patients with lateralized tinnitus, fMRI activation was lateralized towards the side of perceived tinnitus in the primary AC and IC in patients with right-sided tinnitus, and in the MGB in patients with left-sided tinnitus. In healthy volunteers, activation in the primary AC was left-lateralized.

Conclusion

Our paradigm adequately visualized the auditory pathways in tinnitus patients. In lateralized tinnitus fMRI activation was also lateralized, supporting the hypothesis that tinnitus is an auditory phantom phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tinnitus is the perception of sound occurring without an external stimulus. It is a chronic disease with a reported prevalence of 10–15% [1–5]. The effect of tinnitus on quality of life in patients suffering from this disease should not be underestimated: an estimated 20% of patients indicate that their quality of life is significantly diminished. Many patients experience insomnia and depression, and in 1% of the population tinnitus seriously interferes with their life [4–6]. Diagnostic and imaging guidelines are aimed at diagnosing causes for which adequate treatment may be available, but failing that, there is no systematic and proven approach for treating tinnitus [3].

The neural abnormalities underlying tinnitus are largely unknown, despite numerous animal and human studies. In some patients tinnitus can be traced to an internally generated sound (such as vascular structures in pulsatile tinnitus), but in the vast majority no obvious sound source can be established. It has been proposed that tinnitus results from abnormal neuronal activity arising at some point along the auditory pathways which is interpreted as sound at a cortical level [7–9]. This abnormal neuronal activity is hypothesized to be the neural correlate of tinnitus, which is considered to be an auditory phantom phenomenon, similar to central neuropathic pain, due to neural plasticity in response to total or partial deafferentation somewhere along the auditory tract [7, 10–12]. Animal and human studies have provided some evidence for this theory [5, 9, 10, 13–19]. Functional MRI has been applied in a few studies, mainly case studies [20–22]. The most important fMRI study shows an abnormally low percent signal change in the inferior colliculus (IC) contralateral to the side of the perceived tinnitus [23]. This was a study of 13 subjects, only 4 of whom had lateralized tinnitus, which was right-sided in all of them. Although lateralization of abnormally low signal change was therefore suspected to be related to the side of perceived tinnitus, this could not be proven. Also, since the functional imaging was focused on the IC only, nothing is known about the auditory cortex.

The purpose of our study was to visualize the entire central auditory pathway in patients with lateralized tinnitus and in patients with bilateral tinnitus to evaluate lateralization of fMRI signal change and activation clusters.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Between 16 December 2002 and 29 January 2004, 42 patients with refractory, continuous nonpulsatile tinnitus were referred for imaging and localization of the auditory cortex as part of a preoperative work-up for transcranial magnetic stimulation of the auditory cortex. All patients were scanned as part of a clinical protocol that was approved by the participating centers’ medical ethical committees. All patients were classified according to tinnitus sidedness, presence of hearing loss and tinnitus frequencies as established by the referring neurosurgeon. Details of these subgroups are shown in Table 1. In addition, ten healthy volunteers were scanned using the same imaging protocol.

Paradigm

The fMRI paradigm consisted of a blocked design of 12 epochs of 50 s in which lyrical pop music was binaurally presented through headphones. The music was alternatingly switched on and off for 50 s (i.e. per epoch). The subject was instructed to listen to the music attentively. The headphones were dedicated for use in an MRI scanner, attenuating scanner noise by approximately 30 dB. A test run was performed before the start of the actual paradigm, to make sure that the patient was able to hear the music well despite the background scanner noise.

Scan parameters

All imaging was performed on a 3T MRI scanner (INTERA, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) with a six-channel phased-array dedicated head coil.

For functional imaging, a T2*-weighted gradient echo (GE) echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence was used with an echo time (TE) and repetition time (TR) of 33 and 5,000 ms respectively (acquisition matrix 80 × 80, field of view 230 × 230 mm2). We used a clustered volume acquisition technique, in which the acquisition time (AT) was shorter than the TR, namely 2,000 ms, leaving a 3,000 ms silent gap in between each EPI volume acquisition. A sensitivity encoding (SENSE) reduction factor of 2.5 was used. Total scan time per session was 10 min 10 s.

For anatomical reference a high-resolution 3-D T1-weighted turbo field echo (TFE) sequence was used with a TE/TR of 4.60/9.70 ms and an acquired voxel size of 0.98 × 0.98 × 1.20 mm3 (acquisition matrix 256 × 256, field of view 250 × 250 mm2, SENSE reduction factor 3.0; 128 TFE shots). Total scan time was 6 min 25 s. No contrast agent was administered.

Analysis

All data were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping version 2 (SPM2) software (Wellcome Department, University College of London, London, UK).

The functional EPI images were realigned using SPM2’s motion correction algorithm and coregistered with the individual’s T1-weighted scan [24]. All images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) brain template using affine and nonlinear transformation. The normalized EPI images were subsampled to a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 and spatially smoothed with a 3-D gaussian kernel of 6 × 6 × 6 mm3 full-width half-maximum (FWHM) for single subject and group analysis purposes [25].

First-level single subject analysis consisted of modeling the “on” and “off” conditions using a boxcar function convolved with the hemodynamic response function (HRF) using the general linear model (GLM) [26]. Global changes of the signal were adjusted by applying a high-pass filter of 128s to remove low-frequency drifts. Individual statistical parametric maps were generated, that were then used for a second-level random effects (RFX) group analysis after correction for the number of scanning sessions [27]. For qualitative and quantitative analysis we used a significance threshold of P < 0.05 with family-wise error (FWE) correction (P corrected) that is used to correct for the multiple comparisons that are made when simultaneously testing all of the voxels for activation. We used FWE correction for areas of activation in the primary auditory cortex (A1, Heschl’s gyrus) and the secondary auditory cortex (A2, planum polare and planum temporale). For activation in the small subcortical auditory structures (IC and medial geniculate body, MGB), we applied a small volume correction technique (SVC), that only corrects for the multiple comparisons within a specific region of interest. The regions of interest for the IC and the MGB were identified on the mean high-resolution anatomical image and drawn using MarsBar version 0.35 software (Fig. 1) [28]. Anatomical labeling of significantly activated clusters was performed using the MNI space utility (http://www.ihb.spb.ru/~pet_lab/MSU/MSUMain.html) [29, 30].

Regions of interest (ROIs) that were used for the quantitative analysis of activation in (a) the primary auditory cortex, (b) the secondary auditory cortex, (c) the MGB, and (d) the IC. An activation ratio was calculated for each ROI by dividing the number of significantly activated voxels in the ROI on one side by the total number of significantly activated voxels in both ROIs of both sides. The activation ratio for the left primary auditory cortex, for instance, would be the number of activated voxels in the left primary auditory cortex (leftA1) divided by the total number of activated voxels in the left and in the right primary auditory cortex (leftA1+rightA1): leftA1/(leftA1+rightA1)

For qualitative analysis we performed a one-sample t-test for all subjects combined as well as ANOVA to compare the areas of activation in the four different groups of subjects (patients with left-sided, right-sided and symmetrical tinnitus, and healthy volunteers). For quantitative analysis we used the number of activated voxels, with the significance thresholds as mentioned above, and the maximum signal intensity change in the ROIs of the A1 and A2, the IC and the MGB, that were anatomically defined on the mean high-resolution anatomical image. These ROIs were drawn unilaterally and then copied and mirrored to the contralateral side. An activation ratio was then calculated for each ROI, by dividing the number of significantly activated voxels in the ROI on one side by the total number of significantly activated voxels in both ROIs of both sides. Ratios for maximum signal intensity change were calculated similarly. A combination of activation and signal intensity change ratio was calculated by multiplying both ratios. Differences between the left and right side for each ROI were tested for significance (P < 0.05) using a paired-samples t-test (Microsoft Excel 2000).

Results

Subjects

The subjects imaged comprised 42 tinnitus patients and 10 healthy volunteers. The mean age of the patients was 48.4 years (range 26–73 years); 52% of the patients were male. Tinnitus was continuously present in all patients. Tinnitus was lateralized in 35 of the 42 patients (83%), being purely left-sided in 18 patients and purely right-sided in 12. In 5 patients the tinnitus was bilateral but lateralized, being stronger on the left than on the right in 4 patients, and stronger on the right than on the left in 1 patient. For the quantitative and qualitative analyses, these patients were classified as having either left- or right-sided tinnitus according to the side that the tinnitus was lateralized to. Seven patients had bilateral symmetrical tinnitus. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The average age of the healthy volunteers was 29.6 years (range 21–35 years); 6 (60%) were male.

Single subject analysis

Significant activation (P corrected < 0.05) was found in the A1 and A2 in all but one subject. In this one tinnitus patient very little activation was seen in the left A1 and A2, and no activation was found in the right A1 and A2. In 29 patients (69.0%) and in 9 healthy volunteers (90.0%) significant activation (P corrected < 0.05 after SVC) in one of the IC was found; 16 patients (38.1%) and the 9 volunteers showed activation in both IC. Activation (P corrected < 0.05 after SVC) in either one of the MGB was seen in 23 patients (54.8%) and in 7 healthy volunteers (70.0%); 13 patients (31.0%) and 6 volunteers (60.0%) showed activation in both the left and the right MGB.

Qualitative random effects group analysis

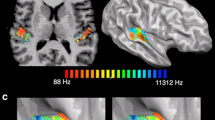

Second-level random effects group analysis of all subjects combined showed significant activation (one sample t-test; P corrected < 0.05) bilaterally in the A1 and A2 and the IC (Fig. 2). After SVC, significant activation at a corrected P value of <0.05 was also observed in the MGB bilaterally. MNI coordinates, anatomical locations, cluster volumes and T values are summarized in Table 2. Considering each group of subjects separately (ANOVA) asymmetrical activation was seen in the auditory cortices in the patient groups with lateralized tinnitus, whereas activation was symmetrical in patients with bilateral symmetrical tinnitus and in the healthy volunteers (Fig. 3). In patients with left-sided tinnitus, activation was less in the right auditory cortex than in the left; in patients with right-sided tinnitus the reverse was seen, with less activation in the left auditory cortex than in the right.

Quantitative group analysis

Activation and maximum signal intensity change ratios were calculated as described in the methods section. The results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 and shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

Activation ratios (error bars indicate the standard errors) in the three different patient groups (left-sided tinnitus, right-sided tinnitus, bilateral tinnitus) and the healthy controls in (a) the primary auditory cortex (A1), (b) the secondary auditory cortex (A2), (c) the medial geniculate body (MGB) and (d) the inferior colliculus (IC) (asterisk significant difference between the left and the right side, P < 0.05; dagger near-significant difference between the left and the right side, P<0.10)

Ratios of maximum signal intensity change (error bars indicate the standard errors) in the three different patient groups (left-sided tinnitus, right-sided tinnitus, bilateral tinnitus) and the healthy controls in (a) the primary auditory cortex (A1), (b) the secondary auditory cortex (A2), (c) the medial geniculate body (MGB), and (d) the inferior colliculus (IC) (asterisk significant difference between the left and the right side, P < 0.05; dagger near-significant difference between the left and the right side, P < 0.10)

A significantly lower activation ratio was seen in the left than in the right A1 in patients with right-sided tinnitus (Table 3; Fig. 4). In patients with left-sided tinnitus, a lower activation ratio was seen in the right than in the left A1, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.08). When combined with the maximum signal intensity change ratio, this difference was significant (0.29 on the left versus 0.23 on the right; P < 0.05). In the MGB a significantly lower activation ratio was seen on the right side in patients with left-sided tinnitus; in patients with right-sided tinnitus the reverse was seen, although this difference in activation ratios again did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.08). When combined with the maximum signal intensity change ratio, the significance level did not change (0.18 on the left versus 0.43 on the right; P = 0.08). A significantly lower activation ratio was seen in the left than in to the right IC in patients with right-sided tinnitus. This difference in activation ratios between the left and the right IC was not observed in patients with left-sided tinnitus. No differences in activation ratios were seen in the A2 in patients with lateralized tinnitus.

A similar lateralization pattern was seen for the maximum signal intensity change ratios (Table 4; Fig. 5). In patients with left-lateralized tinnitus, a significantly lower ratio was seen in the right A1 and A2, and in the A1 and A2 combined. In patients with right-sided tinnitus a significantly lower ratio of signal intensity change was seen in the left A1. In the A2, however, the maximum signal intensity change ratio was lower on the right side. In patients with bilateral, symmetrical tinnitus no differences were found in activation or maximum signal intensity change between the left and right A1 and A2, MGB and IC. In the healthy volunteers, the activation and maximum signal intensity change ratios were higher in the left than in the right A1; no differences were observed between the left and right A2, MGB and IC.

Discussion

In this study we successfully visualized fMRI activation in the cortical and subcortical areas of the auditory system of tinnitus patients using a simple blocked paradigm and an easy to use scanning sequence.

Functional MRI of the auditory system is particularly challenging due to an interaction between the experimental auditory stimuli and the extremely loud background scanner noise [31–33]. As well as being very loud (up to 110 dB), the MRI scanner sound is an amplitude-modulated periodic sound with a complex spectrum, that very likely interacts with the experimentally delivered stimuli [34, 35]. Subjects may also be engaged in processes different from simple auditory perception, because they have to extract the stimulus from the background MR-generated noise. Some attenuation (up to 30 dB) of the background scanner noise can be achieved by using special padded headphones, as used in our study, through which the stimuli are delivered. Silent fMRI techniques, such as the BURST sequence, are very effective in reducing acoustic noise [36], but most tend to be too slow for fMRI studies [37]. Longer noise-free periods—known as sparse temporal sampling—during acquisition are also useful in reducing the amount of scanner-generated noise and have been shown to improve fMRI activation of the auditory system, but the amount of information acquired is usually decreased and acquisition times are long [33, 35, 38]. In our study, we used a “clustered volume acquisition” technique [39–41]. This method has the advantage of a global increase in efficiency, while retaining sufficient silent gaps during which the subject can clearly perceive the auditory stimulus. In this study, our method allowed the successful detection of fMRI activation in both the cortical and subcortical structures without the need for lengthy acquisition times, which makes it easily applicable in clinical practice.

In healthy volunteers, we found a left-lateralized activation of the A1, and symmetrical activation in the other auditory areas. A leftward lateralization of the A1 in healthy subjects has been described previously, both for linguistic and nonlinguistic stimuli [42, 43]. This is thought to be due to the A1’s involvement in language processing, which is also left-lateralized in the majority of people, by screening incoming sounds for speech [44].

In patients with tinnitus, very different patterns of activation were seen. In patients with lateralized tinnitus, we found a lateralization of activation cluster size and/or in maximum signal intensity change in the A1 and in the MGB towards the side of perceived tinnitus. No differences in activation or signal intensity change between the left and the right side were found in patients with symmetrical tinnitus. This lateralization may be due to an increase in activation on the side of the perceived tinnitus, or a decrease in activation on the side contralateral to the side of perceived tinnitus. The latter interpretation would indicate an increased spontaneous neural activity of the affected brain area, such as has been postulated in patients with tinnitus. Since fMRI activation always represents a difference in neural activity, instead of absolute neural activity, an increase in spontaneous neural activity would mean that the affected brain area during the rest condition is more active than the unaffected side, and that the active condition will only give rise to a limited increase in activity (saturation model) [23]. This results in a lower activity on the affected side, which would be the side contralateral to the side of the perceived tinnitus. An alternative explanation would be that the sound of the tinnitus itself is masking the sound of the stimulus (music), which would also lead to less activity on the affected side than on the unaffected side (physiological masking model) [23]. From earlier PET studies, showing increased metabolic activity in the auditory system of patients with tinnitus on the side contralateral to the side of perceived tinnitus compared with healthy volunteers, the saturation model seems more likely, although the results are not conclusive [9, 17, 18]. Our results suggest that the A1 is affected in patients with tinnitus, with a lower fMRI activity on the side contralateral to the side of perceived tinnitus.

In the A2 no significant differences were found between the left and the right side in patients with lateralized or in patients with symmetrical tinnitus. Maximum signal intensity change, however, was significantly higher on the left side in patients with lateralized tinnitus, independent of the side of the tinnitus. This was also seen in patients with symmetrical tinnitus, although this difference was not statistically significant. The A2 is specialized in high-order processing including internal sound representation. In an earlier PET study, increased metabolic activity was found predominantly in the right hemisphere, irrespective of the side of tinnitus [15]. It was postulated that not only simple auditory processing, but also specific higher order cognitive elaboration may be involved in tinnitus perception. Disabling and distressing tinnitus may be associated with activity in functionally linked cortical areas that are predominantly right-hemispheric, subserving the processing of auditory signals, memory and attention [1, 16, 45–47]. This would also account for the discrepancy between the severe adverse effect on patients’ lives compared to the acoustically relatively weak tinnitus sound (>85% does not exceed 10 dB). If there is indeed a spontaneous hyperactivity associated with emotionally modified sound processing in the right A2, listening to music attentively would lead to limited fMRI activity in the right A2 (as explained by the saturation model). The left-lateralized fMRI activity in the A2 that we found may therefore be the result of a higher state of attention and emotional sound processing in tinnitus patients, irrespective of the tinnitus side. Alternatively, it may be due to a physiological left-lateralized activity in the secondary auditory cortex in response to sound, irrespective of the presence of tinnitus, but since no leftward lateralization in the A2 was seen in healthy volunteers, this seems unlikely.

In agreement with Melcher et al., we found less fMRI activation in the left than in the right IC in patients with right-sided tinnitus, which would support the saturation and physiological masking models [23]. We did not, however, find this lateralization of activity in the IC in patients with left-sided tinnitus, in whom we did find a lateralization of activity in another subcortical auditory structure, the MGB. Since our study population was rather heterogeneous, it is difficult to interpret this lack of lateralization in the IC in patients with left-sided tinnitus.

Unfortunately, not all of our results reached the desirable significance threshold of P < 0.05. This is very likely also due to the heterogeneity of our patient group, which forms the main limitation of our study. Our patient group included patients with all degrees of hearing loss, as well as patients with normal hearing. Tinnitus pitch was also varied, as was the quality of tinnitus, including both white noise and purely tonal tinnitus. Unfortunately, our patient population was too small to account for all of these factors by stratifying patients into different subgroups. The main focus of our ongoing research is therefore to expand our study population to be able to account for hearing loss, tinnitus pitch and tinnitus quality, thereby increasing homogeneity of our patient groups and improving the statistical power of our results. Another possible approach to assess brain activity in relation to tinnitus would be to study patients who are able to voluntarily adjust or even provoke tinnitus [21, 22, 48]. In these patients, tinnitus itself could then be used as the stimulus, providing the unique opportunity to directly study tinnitus in relation to brain activity. Unfortunately, these patients are rare, and none of the patients included in our study was suitable for this kind of experiment.

Conclusion

Using a simple fMRI paradigm, we have been able to visualize fMRI activation in both the cortical and the subcortical structures of the auditory pathway, which makes fMRI of the auditory system available for clinical practice. We have demonstrated (near-)significant lateralization of activity in the A1 and in the MGB in patients with lateralized tinnitus, supporting the hypothesis that tinnitus may be considered a phantom auditory sensation with an abnormal neuronal activity. Not only do our results contribute to an increased insight in the neuropathophysiology of tinnitus, but our findings may also be used as a means of objectifying tinnitus in, for instance, animal studies.

References

Axelsson A, Ringdahl A (1989) Tinnitus – a study of its prevalence and characteristics. Br J Audiol 23:53–62

Heller AJ (2003) Classification and epidemiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 36:239–248

Weissman JL, Hirsch BE (2000) Imaging of tinnitus: a review. Radiology 2:342–349

De Ridder D, De Mulder G, Walsh V, Muggleton N, Sunaert S, Moller A (2004) Magnetic and electrical stimulation of the auditory cortex for intractable tinnitus. Case report. J Neurosurg 100:560–564

Muhlnickel W, Lutzenberger W, Flor H (1999) Localization of somatosensory evoked potentials in primary somatosensory cortex: a comparison between PCA and MUSIC. Brain Topogr 11:185–191

Meyershoff W (1992) Tinnitus. In: Meyershoff W, Ria D (eds) Otolaryngology head and neck surgery. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 435–446

Eggermont JJ (2003) Central tinnitus. Auris Nasus Larynx 30 [Suppl]:S7–S12

Jastreboff PJ (1990) Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res 8:221–254

Giraud AL, Chery-Croze S, Fischer G, Fischer C, Vighetto A, Gregoire MC, Lavenne F, Collet L (1999) A selective imaging of tinnitus. Neuroreport 10:1–5

Muhlnickel W, Elbert T, Taub E, Flor H (1998) Reorganization of auditory cortex in tinnitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:10340–10343

Kaltenbach JA (2000) Neurophysiologic mechanisms of tinnitus. J Am Acad Audiol 11:125–137

De Ridder D, Ryu H, Moller AR, Nowe V, Van de Heyning P, Verlooy J (2004) Functional anatomy of the human cochlear nerve and its role in microvascular decompressions for tinnitus. Neurosurgery 54:381–388; discussion 388–390

Chowdhury SA, Suga N (2000) Reorganization of the frequency map of the auditory cortex evoked by cortical electrical stimulation in the big brown bat. J Neurophysiol 83:1856–1863

Robertson D, Irvine DR (1989) Plasticity of frequency organization in auditory cortex of guinea pigs with partial unilateral deafness. J Comp Neurol 282:456–471

Mirz F, Pedersen B, Ishizu K, Johannsen P, Ovesen T, Stodkilde-Jorgensen H, Gjedde A (1999) Positron emission tomography of cortical centers of tinnitus. Hear Res 134:133–144

Mirz F, Gjedde A, Ishizu K, Pedersen CB (2000) Cortical networks subserving the perception of tinnitus – a PET study. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 543:241–243

Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Coad ML, Towsley ML, Wack DS, Murphy BW (1998) The functional neuroanatomy of tinnitus: evidence for limbic system links and neural plasticity. Neurology 50:114–120

Arnold W, Bartenstein P, Oestreicher E, Romer W, Schwaiger M (1996) Focal metabolic activation in the predominant left auditory cortex in patients suffering from tinnitus: a PET study with [18F]deoxyglucose. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 58:195–199

Gardner A, Pagani M, Jacobsson H, Lindberg G, Larsson SA, Wagner A, Hallstrom T (2002) Differences in resting state regional cerebral blood flow assessed with 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT and brain atlas matching between depressed patients with and without tinnitus. Nucl Med Commun 23:429–439

Cacace AT (2003) Expanding the biological basis of tinnitus: crossmodal origins and the role of neuroplasticity. Hear Res 175:112–132

Cacace AT, Cousins JP, Parnes SM, Semenoff D, Holmes T, McFarland DJ, Davenport C, Stegbauer K, Lovely TJ (1999) Cutaneous-evoked tinnitus. I. Phenomenology, pschychophysics and functional imaging. Audiol Neurootol 4:247–257

Ballester M, Lovblad KO, Nirkko AC, Vibert D, Romanet P, Schroth G, Hausler R (2001) Functional MRI of tinnitus – preliminary results using echo-planar imaging (abstract). Neuroimage 13:379

Melcher JR, Sigalovsky IS, Guinan JJ, Levine RA (2000) Lateralized tinnitus studied with functional magnetic resonance imaging: abnormal inferior colliculus activation. J Neurophysiol 83:1058–1072

Friston KJ, Williams S, Howard R, Frackowiak RS, Turner R (1996) Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn Reson Med 35:346–355

Friston KJ, Josephs O, Zarahn E, Holmes AP, Rouquette S, Poline J (2000) To smooth or not to smooth? Bias and efficiency in fMRI time-series analysis. Neuroimage 12:196–208

Worsley KJ, Friston KJ (1995) Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited – again. Neuroimage 2:173–181

Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Price CJ, Buchel C, Worsley KJ (1999) Multisubject fMRI studies and conjunction analyses. Neuroimage 10:385–396

Brett M, Anton J-L, Valabregue R, Poline J-B (2002) Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox (abstract). Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain, vol 16. 2–6 June, Sendai, Japan, p 497

Duncan J, Seitz RJ, Kolodny J, Bor D, Herzog H, Ahmed A, Newell FN, Emslie H (2000) A neural basis for general intelligence. Science 289:457–460

Calder AJ, Lawrence AD, Young AW (2001) Neuropsychology of fear and loathing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2:352–363

Cacace AT, Tasciyan T, Cousins JP (2000) Principles of functional magnetic resonance imaging: application to auditory neuroscience. J Am Acad Audiol 11:239–272

Bernal B, Altman NR (2001) Auditory functional MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 176:1009–1015

Johnsrude IS, Giraud AL, Frackowiak RS (2002) Functional imaging of the auditory system: the use of positron emission tomography. Audiol Neurootol 7:251–276

Cho ZH, Chung SC, Lim DW, Wong EK (1998) Effects of the acoustic noise of the gradient systems on fMRI: a study on auditory, motor, and visual cortices. Magn Reson Med 39:331–335

Elliott MR, Bowtell RW, Morris PG (1999) The effect of scanner sound in visual, motor, and auditory functional MRI. Magn Reson Med 41:1230–1235

Lovblad KO, Thomas R, Jakob PM, Scammell T, Bassetti C, Griswold M, Ives J, Matheson J, Edelman RR, Warach S (1999) Silent functional magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates focal activation in rapid eye movement sleep. Neurology 53:2193–2195

Amaro E Jr, Williams SC, Shergill SS, Fu CH, MacSweeney M, Picchioni MM, Brammer MJ, McGuire PK (2002) Acoustic noise and functional magnetic resonance imaging: current strategies and future prospects. J Magn Reson Imaging 16:497–510

Hall DA, Haggard MP, Akeroyd MA, Palmer AR, Summerfield AQ, Elliott MR, Gurney EM, Bowtell RW (1999) “Sparse” temporal sampling in auditory fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 7:213–223

Edmister WB, Talavage TM, Ledden PJ, Weisskoff RM (1999) Improved auditory cortex imaging using clustered volume acquisitions. Hum Brain Mapp 7:89–97

Yetkin FZ, Roland PS, Purdy PD, Christensen WF (2003) Evaluation of auditory cortex activation by using silent fMRI. Am J Otolaryngol 24:281–289

Kovacs S, Peeters R, Smits M, De Ridder D, Van Hecke P, Sunaert S (2006) Activation of cortical and subcortical auditory structures at 3 T by means of a functional magnetic resonance imaging paradigm suitable for clinical use. Invest Radiol 41:87–96

Yoo SS, O’Leary HM, Dickey CC, Wei XC, Guttmann CR, Park HW, Panych LP (2005) Functional asymmetry in human primary auditory cortex: identified from longitudinal fMRI study. Neurosci Lett 383:1–6

Devlin JT, Raley J, Tunbridge E, Lanary K, Floyer-Lea A, Narain C, Cohen I, Behrens T, Jezzard P, Matthews PM, Moore DR (2003) Functional asymmetry for auditory processing in human primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci 23:11516–11522

Lurito JT, Dzemidzic M (2001) Determination of cerebral hemisphere language dominance with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 11:355–363, x

Gainotti G (1972) Emotional behavior and hemispheric side of the lesion. Cortex 8:41–55

Hallberg LR, Erlandsson SI (1993) Tinnitus characteristics in tinnitus complainers and noncomplainers. Br J Audiol 27:19–27

Mirz F, Gjedde A, Sodkilde-Jrgensen H, Pedersen CB (2000) Functional brain imaging of tinnitus-like perception induced by aversive auditory stimuli. Neuroreport 11:633–637

Cacace AT, Cousins JP, Parnes SM, McFarland DJ, Semenoff D, Holmes T, Davenport C, Stegbauer K, Lovely TJ (1999) Cutaneous-evoked tinnitus. II. Review of neuroanatomical, physiological and functional imaging studies. Audiol Neurootol 4:258–268

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible with funding from a European Union Marie-Curie Fellowship and from “Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO)-Flanders Wetenschappelijke Onderzoeksgemeenschap (WOG) on Advanced Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)”. The authors wish to thank Mr. P. Hamaekers, Senior Research Nurse, for technical support.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

The principal author (M.S.) received funding through a European Marie-Curie Fellowship and from FWO-Flanders WOG on Advanced NMR. The authors’ work was independent of the funding organizations. The funding organizations had no involvement in the study design, data collection and analysis, writing the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smits, M., Kovacs, S., de Ridder, D. et al. Lateralization of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) activation in the auditory pathway of patients with lateralized tinnitus. Neuroradiology 49, 669–679 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-007-0231-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-007-0231-3