Abstract

Purpose

The multiplicity in terms and definitions of medication-related harm has been a long-standing challenge for health researchers, clinicians, and regulatory bodies. The purpose of this narrative review was to report the diversity of terms; compare definitions, classifications, and models describing medication harm; and suggest which may be useful in both clinical practice and the research setting.

Methods

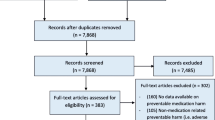

A narrative review of key studies defining and/or classifying medication harm terminology was undertaken.

Results

This review found that numerous terms are used to describe medication harm, and that there is a lack of consistency in current definitions, classifications, and applications. This lack of consistency applied across clinical jurisdictions and regulatory terminologies. A number of limitations in current definitions and classifications were identified. These included the exclusion of key types of medication harm events, ambiguous wording, and a lack of clarity and consensus on subclassifications. In general, there was some overlap in key models from the literature and these were presented to describe similarities and differences.

Conclusion

Without uniformity quantifying, comparing, combining, or extrapolating medication harm data, such as a rate of harm in a specific population, is a challenge for those involved in medication safety and pharmacovigilance. There is a pressing need for further discussion and international consensus on this topic. Adoption of standard descriptors by practitioner groups, regulatory and policy organisations would foster quality improvement and patient safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the most common interventions in healthcare is the use of medications. It is estimated that up to one third of adults in the United States (US) take five or more medications [1]. The decision to use a medication relies on the clinician and patient accepting the risk between effectiveness and toxicity. The clinician must then choose a dose that balances this risk to ensure the desired drug response. This is challenging with medications such as cytotoxic agents, anticoagulants, and immunosuppressants, where the desired therapeutic target is difficult to achieve. In addition, there are responses to medications that are unpredictable even at “typical” doses.

Patient harm from medicines poses a significant burden to the healthcare system. Globally, medication harm results in hospitalisations, increased length of inpatient admissions, and considerable morbidity and mortality [2,3,4]. Medication-related mortality rates range from 0.14 to 4.7% [3,4,5], with medication harm rates ranging between 3 and 35% [3, 6]. The wide range in reported harm is unlikely to be solely due to the variation between patient types and health systems. We suspect this could also be a consequence of inconsistent terminology or descriptors of harm as currently there are multiple terms and definitions used.

In the literature, terms such as adverse drug events (ADEs), adverse drug reactions (ADRs), potential ADEs, medication errors (MEs), and drug-related problems (DRPs) are often used interchangeably based on researcher preference. Whilst conducting a systematic review of predictive risk scores for inpatient ADEs, we encountered a major challenge with the heterogeneity of terms used as the main outcome of studies [7]. Some studies measured ADEs, others measured ADRs, and some referred to MEs or DRPs as their main outcome.

In addition to the diverse terminology, there are also numerous definitions and classifications for each term. For example, in our systematic review, the six studies that measured ADRs used three different definitions [8, 9]. There were similar issues with definitions for ADEs and DRPs. This lack of homogeneity suggests a need for clarification of widely used terms and definitions.

The inconsistencies in medication safety terminology are widespread and have been previously identified as a challenge [10]. As a result, patient safety bodies revert to multiple terms when describing safety outcomes. After searching 116 websites, Yu et al. identified 25 different terms with 119 definitions. These included adverse event, error, near miss, and adverse reaction. The authors concluded that accurate analysis of incidence data requires standardisation of nomenclature [11]. Another systematic review of definitions of MEs found that in the 203 studies that measured MEs as a primary outcome, 26 different definitions were used [12]. These studies reinforce that incongruous terminology is an obstacle to reporting and comparing research findings.

Medication harm requires uniform terminology and definitions. This would not only enable precise comparison of event rates but also help clinicians better interpret reports evaluating the prevalence and severity of harm. Furthermore, standardisation would improve communication between patients, clinicians, researchers, and policy makers to help raise awareness of the true extent of medication harm.

Purpose

The purpose of this narrative review is to report the diversity of terms related to medication harm; describe widely used terms, their definitions, classifications, and models where presented; and suggest which may be useful in clinical practice and research settings.

Definitions and discussion

There are a number of key terms related to medication harm that are commonly used in the literature and by medication safety and pharmacovigilance bodies. Widely used terms and definitions and respective models are described in Table 1.

As described in Table 1, some models have expanded on the works of others, with an evolution of the content and construct of terms. For example, the models by Morimoto, the American Society of Health-system Pharmacists, and Nebeker et al. appear to be inspired by earlier work by Bates (although there are differences in interpretation), or the DRP definition by the Pharmaceutical Care Network of Europe (PCNE) clearly aligns with the original definition proposed by Hepler and Strand.

Key terms

Medication harm

Medication harm is used in this manuscript to describe any negative patient outcomes or injury, related to medication use, irrespective of severity or preventability.

Medication errors

Medication errors (MEs) are a widely used term which feature as a subset of many definitions for medication harm. MEs can be divided into two groups based on outcome. The first group includes MEs which are identified and corrected before reaching the patient or are clinically insignificant and reach the patient but do not cause harm. The second group is those that reach the patient, are clinically significant, and result in an undesirable patient response. Multiple definitions have been proposed for MEs [14, 20, 32]. Bates defines MEs as “errors in the process of ordering or delivering a medication” [14]. Aronson and Ferner use a similar definition [32]. They imply that therapy has fallen “short of some standard in care” and that harm includes treatment failure from a “lack of benefit” [32]. Another frequently used definition is by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP), who advocate an outcome-based classification system, dividing MEs into nine categories (A to I), where A–D are no harm and E to I are errors resulting in harm [20].

Adverse drug events and adverse drug reactions

The WHO definitions

An early definition of adverse drug events (ADEs) by the World Health Organization (WHO) is “any untoward medical occurrence that may present during treatment with a pharmaceutical product but that does not necessarily have a causal relation to the treatment” [8]. This definition includes adverse drug reactions (ADRs), as well as harm from MEs.

ADRs according to the WHO are “a response to a drug which is noxious and unintended and which occurs at doses normally used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or the modification of physiological function” [8]. According to this definition, if a patient experiences harm where there is a causal relationship between the medication and the reaction, this should be referred to as an ADR rather than as an ADE. However, this term is often used interchangeably with ADEs. Causality, in the context of ADR detection, has been described as establishing a relationship between a patient’s response and a medication when used at normal doses. Causality can be assessed using a number of tools [33,34,35].

There are two key aspects to applying the WHO ADR definition: establishing causality and ascertaining if a suspected medication was used appropriately, in that it was prescribed at normal dosages, frequencies, and routes and administered at the correct time to the correct patient [36]. The WHO definition of ADRs excludes harm from MEs, for example where a medication for patient X is incorrectly given to patient Y, resulting in harm. This is a potential limitation of this definition as distinguishing between the two types of events is not always clear. Some ADRs arise as a result of errors, and what is considered a “normal” dose in one individual can be toxic for another, for example a patient who is administered a high dose of an anticoagulant and experiences bleeding. Is this interpreted as an ADR, an ME-related ADE (a lower dose should have been used), or both? Clear classification of event types can be a challenge. Unlike the WHO definition for an ADR, some definitions discussed later show an overlap in the relationship between ADRs and MEs and may be more appropriate.

Adverse drug reactions and their classification

In 1977, Rawlins and Thompson suggested two types of adverse drug reactions (ADRs): type A reactions which are common, expected, and dose dependant and type B reactions which are uncommon and not expected from the normal pharmacological properties of the drug, such as hypersensitivity reactions [16]. As early definitions were deemed too simplistic, Edwards and Aronson described ADRs as “An appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction, resulting from an intervention related to the use of a medicinal product, which predicts hazard from future administration and warrants prevention or specific treatment, or alteration of the dosage regimen, or withdrawal of the product” [9]. Here, ADRs are described as “appreciably harmful” reactions, to deliberately exclude minor harm which is not viewed as useful in ADR surveillance. They expanded ADR classification by adding four types of reactions (Supplementary Table 1). In later work, type G for genomic-related ADRs was added [37]. Whilst comprehensive, these definitions can be challenging to apply, as there is overlap between some types of reactions. For example, a dose-related ADR could also be a genomic-related ADR. Furthermore, there can be uncertainty assigning a reaction to one ADR type, for example, is the diarrhoea secondary to the antibiotic erythromycin a type A or type B reaction? [37].

Aronson and Ferner argue that the term ADE is superfluous [23]. Their model refers only to ADRs and harm caused by MEs which could include harm from non-adherence, untreated indications and unintentional omissions. These latter events causing harm are often excluded from definitions of ADRs but included as part of the broader term ADE.

Adverse drug events

Adverse drug events (ADEs) have been defined by Bates as “injuries resulting from medical intervention related to a drug” [14]. This definition originates from the Harvard Medical Practice Study and has been adopted by the Institute of Medicine [38, 39]. Bates’ definition includes potential ADEs, or MEs which have potential for harm, but are intercepted before reaching a patient. These MEs have been termed “near misses” or “close calls”. The ADE definition also includes MEs that cause patient harm (Table 1). Although widely used, this definition has been criticised as vague [10], as it is unclear which other events make up the remaining ADEs.

Morimoto et al. later expanded this definition, and similar to the WHO ADE definition separated harm into MEs (one third of ADEs) and ADRs (two thirds of ADEs) [19]. Morimoto describes ADRs as non-preventable events, in contrast to harm from MEs which are considered preventable [18]. ADRs are defined as side effects of medications or allergic reactions. Morimoto’s definition also separates ADRs from MEs that cause harm, as illustrated in Table 1.

Terms and definitions used by safety and regulatory bodies

Terms and definitions for medication harm, used by seven international medication safety bodies and regulation agencies, are shown in Table 2. A clear theme is that safety bodies prefer ADEs, whereas regulatory agencies use the term ADRs. For safety bodies, this is likely influenced by a focus on the identification of causes and prevention of harm due to system failures. Regulatory agencies are primarily concerned with post marketing surveillance of medications and previously unknown reactions and prefer the term ADRs.

In order to standardise the scientific and technical aspects of drug regulation, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) developed the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) as a multilingual tool for standardised communication of clinical data [40]. They define ADRs using the WHO definition but modified it to include harmful reactions at any dose [28].

Do medication errors and adverse drug reactions overlap?

With the continued debate, Nebeker defined an ADE as “any physical or mental harm resulting from medication use, be it misuse, under-dosing or overdosing” [18]. This definition divides ADEs into the following five groups: adverse drug reactions (ADRs), medication errors (MEs) that result in harm, therapeutic failures, withdrawals, and overdoses.

In contrast to earlier definitions, Nebeker’s model shows a clear overlap between ADRs and MEs that cause harm [18]. This has been criticised by those who believe that ADRs should not overlap with harm from MEs [22]. In keeping with Morimoto’s earlier work, Otero and colleagues argue that because all ADRs are due to an intrinsic property of a drug they cannot be prevented. This is in contrast to MEs which are always preventable and generally a result of poorly designed systems. By this definition of preventability, no ME-related harm can also be an ADR. This is debatable, as it has been argued that not all MEs are preventable [18, 41]. More importantly, irrespective of whether an error is involved, harm from medications is usually, at least to some degree, due to a medication’s pharmacological properties (except for type B or immune-mediated reactions). For example, if a patient receives a high dose of gentamicin causing nephrotoxicity, this could be classified as a type A ADR (supplementary Table 1). However, it may also be classified as a ME-related ADE, due to poor prescribing and/or a lack of patient monitoring. This illustrates how an ADE may be both an ADR and also a ME [37].

A more recent model for ADEs also distinguishes between harm from MEs and harm from ADRs as distinct entities which are related but not identical. Burkel’s model describes MEs as part of the medication management pathway (Table 1). ADEs, which can result from MEs or ADRs (but not both simultaneously), are clinical events related to medication use. This model also separates ADRs from MEs that cause harm. The authors give a case example which they classify as an ADR but not a ME: a drug interaction in a patient prescribed both diltiazem and simvastatin, causing creatinine kinase elevation. Again, this could be classified as both a ME-related ADE and also an ADR.

What is missing from these definitions?

A limitation of these definitions is the lack of clarity of harm resulting from medication non-adherence, misuse, untreated indications, and omissions of therapy, for example where a patient is unintentionally not prescribed warfarin and consequently suffers a cerebrovascular event. As there is no causal relationship with a drug, they often remain undefined [10]. As suggested by Aronson and Ferner [23], the term “adverse events” could be used to describe such harm where a drug is not directly implicated. Burkel’s model explicitly includes a category for harm from omission errors, separate to ADEs (Table 1), which is useful for a commonly encountered clinical problem.

Drug-related problems

Drug-related problems (DRPs) have been defined as “an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with the patient experiencing an optimum outcome of medical care” [42]. The term DRP can refer to both processes that may result in harm (MEs or potential harm) and outcomes (observed harm). Strand et al. divided DRPs into eight groups (Table 3) [13]. Similar to issues with classifying ADRs, there is overlap. For example, co-administration of citalopram and tramadol causing serotonin syndrome could be classified as both an ADR (type 6) and also a drug interaction (type 7) (Table 3).

An advantage of this classification is the patient-centric interpretation of the different groups of DRPs. Conceptualising potential or actual harm with the patient in mind is helpful for identifying interventions that can prevent such problems, for example deprescribing where there is no valid indication. Hepler and Strand’s philosophy of pharmaceutical care, which helped define DRPs, aimed to describe how pharmacists could improve therapeutic outcomes in a patient-centred manner [42]. Their early work forms the basis for later definitions and classifications of DRPs [10, 17, 24]. In 2006, Akroyd-Stolarz proposed a new DRP model (Table 1), to help describe the relationship of existing medication harm terminology [10]. These include medication misadventure, drug-related morbidity (a term describing serious harm events), and drug therapy problems (or latent medication harm) [10]. The PCNE Classification of DRPs, which has undergone multiple iterations, also uses the definition by Hepler [42]. According to the PCNE, DRPs comprise of causes (or MEs) and problems (actual patient harm) [24].

Why should we standardise?

The limitations in current terminology mean that quantifying, comparing, or extrapolating medication harm data at a clinical level is challenging. For example, in hospitals, medication harm might be detected by a doctor, reported by a different clinician, and coded by non-clinical staff, all of whom may use different terms to document the event. A focus group study of “Barriers to reporting adverse drug events in hospitals” found that healthcare professionals could not provide a definition for ADEs, ADRs, and MEs in accordance with their own local or national reporting guidelines. The lack of consistency of the terms and a validation of patient-incident data is thought to contribute to low reporting rates [43, 44]. A lack of reporting can have implications for policy, funding, and implementation of safety measures.

There is also an increasing need for standardisation with the growing availability of electronic health record data. This data is being used for meta-analytics and machine learning, methods that create new solutions to existing health problems. In addition, risk prediction algorithms will help with identification of patients at high risk of harm but these need reliable data, which can only be assured with consistent terminology and definitions.

Currently, coding of patient medical records is used to classify medication harm in hospitals (International Classification of Diseases (ICD)). Studies have utilised ICD-10 codes as a practical means to identify and evaluate the impact of serious and rare ADRs at a population level [45]. However, as described in a systematic review of ICD-10 codes, “the inconsistency in operational definition of adverse drug events needs to be addressed before being able to achieve consensus on a common code set(s)” [46].

Where to next?

This narrative has highlighted the diversity in terms and definitions to describe medication harm. We suspect that a root cause of this issue is that the terminology has evolved from two paradigms – a quality and safety perspective and a pharmacovigilance approach. Whilst over time there has been an evolution of our understanding, attempts to merge these approaches have resulted in marked diversity of terms, definitions and models.

What is now needed is consensus, with a standard set of terms and definitions that can be used across settings, including healthcare, research, and regulatory institutions. One step towards international consensus would be for leading health agencies, such as the WHO or the International Union of Pharmacologists, to revisit terminology, and develop a framework to evaluate existing taxonomy.

A suggested starting point could be to stipulate a “base model” that uses constant parameters to describe harm. To ensure consistency, researchers and clinicians must report data based on this model. Whilst it may be difficult to reduce to one initial model given the complexity of terms, we envisage a user-friendly model that focusses on patient outcomes (versus processes), such as the model by Aronson et al. could serve as a suitable starting point from which terminology could flow. Further work on standardisation should be undertaken using systematic methods, versus current descriptive definitions which seem to be based on opinion, for example through use of a theoretical framework and consensus methods, where the terms, definitions, and classifications are examined critically and debated amongst experts.

Limitations

We did not set out to conduct a systematic review. Our narrative review has included definitions from key studies.

Conclusion

Current medication harm terminology and definitions which are inconsistent do not allow clinicians and researchers to describe or compare data with confidence. We urge consensus from leading regulatory and research bodies regarding terms, definitions, and classifications of events.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medication Errors 2017. Available from: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/23/medication-errors

Davies EC, Green CF, Taylor S, Williamson PR, Mottram DR, Pirmohamed M (2009) Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: a prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes. PLoS One 4(2):e4439

Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN (1998) Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 279:1200–1205

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ et al (2004) Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18820 patients. BMJ 329(3)

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL (2011) Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 365(21):2002–2012

Trivalle C, Burlaud A, Ducimetière P (2011) Risk factors for adverse drug events in hospitalized elderly patients: a geriatric score. European Geriatric Medicine 2(5):284–289

Falconer N, Barras MA, Cottrell WN (2018) Systematic review of predictive risk models for adverse drug events in hospitalised patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 84(5):846–864

World Health Organisation. Glossary of Patient Safety Concepts and References 2009

Edwards IR, Aronson JK (2000) Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis and management. Lancet 356(9237):1255–1259

Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Hartnell N, McKinnon NJ (2006) Demystifying medication safety: making sense of the terminology. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2:280–289

Yu KH, Nation RL, Dooley MJ (2005) Multiplicity of medication safety terms, definitions and functional meanings: when is enough enough? Qual Saf Health Care 14:358–363

Lisby M, Nielsen LP, Brock B, Mainz J (2010) How are medication errors defined? A systematic literature review of definitions and characteristics. Int J Qual Health Care 22:507–518

Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ, Ramsey R, Lamsam GD (1990) Drug-related problems: their structure and function. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 24:1093–1097

Bates DW, Boyle DL, Vander Vliet MB, Schneider J, Leape L (1995b) Relationship between medication errors and adverse drug events. J Gen Intern Med 10:199–205

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (1998) Suggested definitions and relationships among medication misadventures, medication errors, adverse drug events and adverse drug reactions. Am J Health Syst Pharm 55:165–166

Rawlins M, Thompson JW (1977) Pathogenesis of adverse drug reactions: textbook of adverse drug reactions. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Meyboom RH, Lindquist M, Egberts AC (2000) An ABC of drug-related problems. Drug Saf 22(6):415–423

Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH (2004) Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician’s guide to terminology, documentation and reporting. Ann Intern Med 140:795–801

Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Seger AC, Hsieh TC, Bates DW (2004) Adverse drug events and medication errors: detection and classification methods. Qual Saf Health Care. 13(4):306–314

National Coordinating Centre for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP). Taxonomy for Medication Errors 2005 [cited 2018 5 Jan]. Available from: http://www.nccmerp.org/taxonomy-medication-errors-now-available

Otero López MJ, Dominguez-Gil A (2000) Adverse drug events: an emerging pathology. Pharm Hosp 24(4):258–266

Otero MJ, Schmitt E (2005) Comments and responses: Clarifying terminology for adverse drug events. Ann Intern Med 142:77

Aronson JK, Ferner RE (2005) Classification of terminology in drug safety. Drug Saf 28(10):851–870

The PCNE Classification V 7.0 [Internet]. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe Foundation. 2016 [cited 19th March 2017]. Available from: http://www.pcne.org/working-groups/2/drug-related-problems

Bürkle T, Müller F, Patapovas A, Sonst A, Pfistermeister B, Plank-Kiegele B, Dormann H, Maas R (2013) A new approach to identify, classify and count drug-related events. Br J Clin Pharmacol 76:56–58

Canadian Patient Safety Institute. The Economics of Patient Safety in Acute Care - Technical Report 2018. Available from: http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/search/pages/results.aspx?k=adverse%20drug%20events

European Medicines Agency. Question and answer document on the European database of adverse drug reaction reports website London2012. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2012/05/WC500127958.pdf

International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH). Post-Approval Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting 2003. Available from: http://www.ich.org/home.html

Institute For Healthcare Improvement (IHI). Adverse Drug Events per 1000 2018. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Measures/ADEsper1000Doses.aspx

Institute for Safe Medication Practices. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Adverse drug reactions: documentation is important but communication is critical Horsham, PA.2018. Available from: http://www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20000906.asp

Therapeutic Goods Administration. Reporting adverse drug reactions 2014. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/publication/reporting-adverse-drug-reactions#whattoreport

Aronson JK (2009) Medication errors: definitions and classification. Br J Clin Pharmacol 67(6):599–603

The use of the WHO-UMC system for standardised case causality assessment [Internet]. Uppsala Monitoring Centre. [cited 2 Jan 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/WHOcausality_assessment.pdf

Naranjo CA, Busto U, SE M, Sandor P, Ruiz I (1981) A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 30:239–245

Hallas J, Harvald B, Gram LF, GRODUM E, BROSEN K, HAGHFELT T et al (1990) Drug related hospital admissions: the role of definitions and intensity of data collection, and the possibility of prevention. J Intern Med 228(2):83–90

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Peterson LA, Small SD, Servi D et al (1995a) Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 274:29–34

Aronson JK, Ferner RE (2003) Joining the DoTS: new approach to classifying adverse drug reactions. BMJ 327(7425):1222–1225

Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Barnes BA, Hebert L, Newhouse JP, Weiler PC, Hiatt H (1991) The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med 324(6):377–384

Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS (1999) To err is human - building a safer health system. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH). Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities MedDRA - version 20.0 2017. Available from: https://www.meddra.org/how-to-use/support-documentation?current

Aronson JK, Ferner RE (2010) Preventability of drug-related harms — part II. Drug Saf 33(11):995–1002

Hepler CD, Strand LM (1990) Oppurtunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 47:533–543

Mirbaha F, Shalviri G, Yazdizadeh B, Gholami K, Majdzadeh R (2015) Perceived barriers to reporting adverse drug events in hospitals: a qualitative study using theoretical domains framework approach. Implement Sci 10:110

Evans SM, Berry JG, Smith BJ, Esterman A, Selim P, O’Shaughnessy J, DeWit M (2006) Attitudes and barriers to incident reporting: a collaborative hospital study. Qual Saf Health Care 15(1):39–43

Walter SR, Day RO, Gallego B, Westbrook JI (2017) The impact of serious adverse drug reactions: a population-based study of a decade of hospital admissions in New South Wales, Australia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 83:416–426

Hohl C, Karpov A, Reddekopp L, Stausberg J (2014) ICD-10 codes used to identify adverse drug events in administrative data: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 21:547–557

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Key points

• Multiple terms and definitions are used to describe medication harm in research and clinical practice.

• The lack of consistency makes it challenging to quantify the true burden of medication-harm, or to make meaningful extrapolations from harm data.

• There is a pressing need for adoption of standard terms and definitions for medication harm.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Falconer, N., Barras, M., Martin, J. et al. Defining and classifying terminology for medication harm: a call for consensus. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75, 137–145 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-2567-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-2567-5