Abstract

Purpose

Breastfeeding women may suffer from migraine. While we have many drugs for its treatment and prophylaxis, the majority are poorly studied in breastfeeding women. We conducted a review of the most common anti-migraine drugs (AMDs) and we determined their lactation risk.

Methods

For each AMD, we collected all retrievable data from Hale’s Medications and Mother Milk (2012), from the LactMed database (2014) of the National Library of Medicine, and from a MedLine Search of relevant studies published in the last 10 years.

Results

According to our review, AMDs safe during breastfeeding are as follows: low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), ibuprofen, sumatriptan, metoprolol, propranolol, verapamil, amitriptyline, escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, acetaminophen, caffeine, and metoclopramide. AMDs compatible with breastfeeding but warranting caution are as follows: diclofenac, ketoprofen, naproxen, most new triptans, topiramate, valproate, venlafaxine, and cyproheptadine. Finally, high-dose ASA, atenolol, nadolol, cinnarizine, flunarizine, ergotamine, methysergide, and pizotifen are contraindicated.

Conclusions

According to our review, the majority of the revised AMDs were assessed to be compatible with breastfeeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Migraine is one of the most frequent form of headache. It is well known that its prevalence is higher among women (12–25 %) than men (5–9 %) [1], particularly in the reproductive age [2]. Most women experience remission during pregnancy [2]. It has been reported that compared to pregnancy, there may be a postpartum increase in the mean intensity and duration of headaches, as well as in the mean number of analgesics used [3]. Although breastfeeding women have a lower recurrence rate than bottle feeding women, more than half of breastfeeding women experience migraine recurrence within 1 month from delivery [4]. Thus, pharmacological treatment of migraine may be needed during lactation [5].

When treating migraine, it is important to identify the factors which can trigger or exacerbate migraine attacks, in order to choose the necessary precautions [6]. Anti-migraine drugs (AMDs) are hence divided into drugs used for acute attacks [7] and those for prophylaxis [8]. The first are subdivided into three major classes: (1) nonspecific agents such as non-steroidal analgesics (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen; (2) triptans, which act specifically on the underlying mechanisms of migraine pain; and (3) ergot alkaloids, such as ergotamine tartrate. Other nonspecific medications such as antiemetics (metoclopramide) are occasionally used to control acute symptoms of nausea and vomiting. Nowadays, ergot alkaloids, together with caffeine, are rarely prescribed because of the superior efficacy and safety of triptans. Prophylactic AMDs are indicated if a disabling attack occurs two or more times a month or in case of severe attacks lasting for several days [9]. Once considered first choice for prophylaxis, methysergide and pizotifen have been gradually replaced by beta blockers (propranolol, atenolol, metoprolol, timolol), calcium channel antagonists (flunarizine, cinnarizine, verapamil), and antidepressants (amitriptyline, escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine). In selected cases, some anticonvulsants (valproate sodium, topiramate) can also be used for prophylaxis.

Given the high prevalence of migraine among women, even in the postpartum period, the question of the choice of the most appropriate and safest AMD may arise during breastfeeding. The aim of this paper is to review the safety profile of AMDs during breastfeeding, helping clinicians to give a competent advice to nursing mothers.

Materials and methods

Drugs considered in the present review have been chosen as the most frequently used in the treatment and prophylaxis of migraine. Before assessing the lactation risk of each AMD, we have collected information on their main pharmacokinetic parameters: half-life (T½), maternal plasma protein binding (PB), milk-to-plasma ratio (M/P), oral bioavailability (see Box 1 for definitions). We decided to collect data on AMDs pharmacokinetic parameters as they represent the theoretical basis on which the lactation risk assessment is initially, although not exclusively, built-up. As an example, the maternal plasma level of a drug with a short half-life (e.g., <3 h) will be significantly lower in breast milk if the infant feeds after 2–3 h from maternal drug consumption. Moreover, a highly protein bound drug will be impeded to enter the milk compartment. Milk/plasma (M/P) ratio indicates the extent of drug transfer into milk; nevertheless, its use in assessing the lactation risk is limited, as drugs with a high M/P ratio might be safer for the nursing infant, than others with a low M/P ratio. Finally, medications used during breastfeeding should have a low oral bioavailability, as the result of either a poor gut absorption or liver sequestration prior to entering the plasma compartment.

Box 1: Definitions and clinical relevance of the pharmacokinetic parameters used to assess the lactation risk following maternal intake of medications (all definitions are drawn from ref 11)

Pharmacokinetic parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

Half-life or “T½” | It is the time it takes for a substance to halve its plasma concentration. If the half-life is long (>12–24 h), drugs may accumulate in breast milk. |

Maternal plasma protein binding (PB) | The higher the percentage of the drug bound to the maternal plasma proteins, the less the drug passes into breast milk. An ideal plasma protein binding should be >80 %. |

Milk-to-plasma ratio (M/P) | It denotes the ratio of the drug concentration in the mother’s milk (M) divided by its concentration in the mother’s plasma (P). A M/P ratio greater than 1.0 suggests that the drug may be present in breast milk in high concentrations. |

Oral availability | It describes the fraction of one orally administered dose of a drug that reaches the systemic circulation. |

Beyond presenting pharmacokinetic parameters on AMDs, we chose to collect some relevant clinical parameters such as the theoretical infant dose (TID), the therapeutic dose in the neonatal period, and the relative infant dose (RID). TID is the maximum estimated amount of ingested drug with breast milk, expressed in milligrams per kilogram per day (mg/kg/day). We calculated it by using the formula: TID = daily breast milk intake (150 ml/kg/day) × maximum breast milk concentration of the medication [9]. As some AMDs may be used in the neonatal period, we presented their therapeutic dose, expressed in milligram/kilogram/day in order to have a direct comparison with the TID. A neonatal therapeutic dose higher than its TID reassures of the drug safety during lactation.

RID is calculated by dividing the infant dose via milk in “mg/kg/day” by the maternal dose in “mg/kg/day,” assuming a 70-kg weight of the mother. Anything less than 10 % of the maternal dose is considered probably safe [10].

To review the lactation risk of AMDs, we consulted the following two most accredited English sources: Medications and Mother’s Milk 2012 [11] and Lactmed database (in TOXNET) [12] of the National Library of Medicine. In his textbook, which is updated every 2 years, Hale collects data on many current medications and their use during breastfeeding [11]. After evaluating information on drug-specific pharmacokinetics and what is currently published in the scientific literature for each drug, including its reported side effects, he makes a personal recommendation, using five categories of lactation risk: L1—safe drugs at the highest level; L2—safe drugs; L3—moderately safe drugs; L4—drugs possibly dangerous; L5—contraindicated drugs [9]. LactMed database is part of the National Library of Medicine’s Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET), and it includes information on the levels of drugs and other chemicals to which breastfeeding mothers may be exposed in breast milk and infant blood, together with the possible adverse effects in the nursing infant [12]. All data published in LactMed are derived from a review of the current scientific literature and fully referenced. LactMed is accessible from common personal computers or electronic devices, visiting TOXNET’s website (http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov), and then choosing LactMed section [12]. LactMed is free and updated regularly.

To complete our synopsis, we have performed a non-systematic Medline search of the literature with the keywords “migraine drug” and “breastfeeding,” retrieving studies from 2004 to 20 August 2014, including the most relevant and updated studies on lactation risk, which might have not included in LactMed and Hale’s textbook.

For each AMD, we organized the relevant data into small summaries.

As the result of the review of all the above information, we classified AMDs into three categories: safe, moderately safe, and contraindicated during breastfeeding. The category “safe” during breastfeeding includes medications of large use in breastfeeding mothers without any relevant, observed adverse effects. The “moderately safe” category has a less documented safety profile due to a short clinical experience and/or lack of studies. The moderately safe AMDs can be prescribed with caution; although the lowest dose of the drug should be better chosen, the nursing infant should be monitored and, when possible, his drug plasma level should be measured. The category “contraindicated” during breastfeeding refers to drugs for which there is a relevant and documented risk for the nursing infant that outweighs the known benefits for the mother–infant couple.

Results

We summarized the pharmacokinetic parameters of AMDs in Table 1. In Table 2, we have given an overview of the clinical relevant parameters for each AMD (TID, therapeutic dose, RID) together with the assessment of its lactation risk according to our study group.

NSAIDs

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)

Maternal ingestion of ASA is associated with the excretion of both salicylate and salicylate metabolites into breast milk. ASA is rapidly metabolized to salicylic acid within approximately 2 h in adults [13], whereas its metabolite, salicylic acid, has a much longer half-life. In a 9-day-old breastfed infant, serum level of salicylate was 6.5 mg/dL following a maternal intake of 2.4 g aspirin [14]. Following maternal intake of 975 mg, 1 mg/dL of salicylate has been reported [15].

Some pediatric concerns on the compatibility of high-dose maternal aspirin with breastfeeding are raised after the publication of two case reports many years ago. The first report documented the occurrence of thrombocytopenia in a 5-month-old breastfed infant possibly caused by salicylate in the breast milk of the febrile wet nurse treated with aspirin [16]. The second study described a case of metabolic acidosis in a 16-day-old whose mother was taking 3.9 g aspirin per day [17].

Prolonged use of anti-inflammatory dosages of acetylsalicylic acid should be avoided in breastfeeding mothers, as its risk is not well documented. Instead, the current practice of using 75–162 mg/daily acetylsalicylic acid to prevent clotting has not yet been reported to cause adverse infant outcomes, as breast milk drug levels would be presumably hardly detectable. According to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, low-dose ASA may be considered safe for use in breastfeeding women [18] as long as the infant has no viral infection or high temperature, as both these conditions may be potential triggers of Reye syndrome [19].

Nevertheless, ibuprofen and acetaminophen are considered preferable to ASA for the treatment of febrile illnesses in breastfeeding women (see below).

Hale classifies ASA as L3. LactMed advices not to breastfeed for 1–2 h after taking aspirin to minimize effect on platelets and to monitor infant salicylate serum levels especially in newborns [12].

Diclofenac

Diclofenac is poorly excreted in maternal milk [12]. In a study, which did not specifically evaluate risks of medication exposure in maternal milk, no adverse effects were observed in infants breastfed by mothers using diclofenac to control pain after cesarean section [20].

In summary, diclofenac is considered compatible with breastfeeding (L2 according to Hale), but other drugs with better lactation risk profile are preferable, especially in newborns or preterm infants [5, 12, 21].

Ibuprofen

Ibuprofen has a short half-life without active metabolites and a low excretion in maternal milk. In fact, it is found in low concentrations in maternal milk (<1 mg/L) of women who take up to 400 mg of ibuprofen every 6 h [22]. Consequently, the amount of ibuprofen possibly absorbed by the nursing infant is much lower then the dose used to treat fever and pain in children (5–10 mg/kg/dose) [23] and patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants (four consecutive 5–10 mg/kg/dose IV or oral) [24, 25]. The RID ranges from 0.1 to 0.7 % [11].

In summary, ibuprofen is considered safe during breastfeeding (L2 for Hale) [26] and it is the anti-inflammatory drug of choice in breastfeeding women [12, 21, 26].

Ketoprofen

In the maternal milk of 18 women receiving 200 mg/day ketoprofen IV postpartum, its concentration ranged between 20 and 177 μg/L; in 17 out of 61 milk samples analyzed, it was undetectable (<20 μg/L) [27]. Although ketoprofen has low levels in breast milk, adverse renal and gastrointestinal side effects have been reported in the nursed infants; consequently, LactMed advises to prefer other agents [12], while Hale classifies it as an L2 [11].

Naproxen

In their recent study on NSAID prescribing precautions, Risser et al. [28] suggested that naproxen was compatible with breastfeeding because of its minimal concentrations (approximately 2 mg/dL) in maternal milk [29]. However, naproxen has a long half-life (12–15 h). Prolonged bleeding time, hemorrhage, and anemia were reported in a 7-day-old baby breastfed by a mother taking naproxen in combination with bacampicillin [30]. Furthermore, in a prospective telephone follow-up of adverse reactions in breastfed infants exposed to maternal medications, 2 out of 20 newborns were reported to have experienced somnolence and vomiting following exposure to naproxen, which did not, however, require medical attention [31]. Therefore, other NSAIDs are preferable to naproxen in breastfeeding women, especially while nursing a newborn or preterm infant [12]. Hale considers its occasional use safe, but its chronic use less so (L4) [11].

Triptans

Triptans are serotonin receptor agonists. Generally well tolerated, these drugs have dose-dependent side effects including: dizziness, paresthesia, nausea, vomiting, somnolence and fatigue, dry mouth, facial flushing, and tightness in the chest, throat, and neck. All share a potential vasoconstrictor action on coronary vessels. Triptans are therefore contraindicated in patients with documented vasculopathy and coronary artery disease, as well as in those at risk of undiagnosed coronary disease (i.e., smoking, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, obesity, or a family history of coronary artery disease) [32].

Almotriptan

There are no data on its safety during breastfeeding. Although considered by Hale possibly compatible with breastfeeding (L3) [11], it has the highest oral bioavailability (70–80 %) among triptans. Because so little is known about this compound, according to LactMed, other drugs are preferable in breastfeeding mothers, especially while nursing a newborn or preterm infant [12].

Eletriptan

Studies on its use during breastfeeding do not contraindicate this drug, due to its low levels into breast milk, but data are scarce [33]. Its oral bioavailability is 50 % and its maternal milk concentration is reported to be low (1.7 μg/L) following doses of 80 mg/daily. The RID is only 0.02 % [11]. However, as far as we know, no studies have tried to measure the concentration of eletriptan active metabolites, whose plasma half-lives are longer [34]. No adverse effects are expected in breastfed infants, especially if older than 2 months [12]. Hale classifies eletriptan as L3 [11].

Frovatriptan

There are no data on its use during breastfeeding. Hale includes frovatriptan in the L3 category [11]. Other triptans are preferable, given its long half-life (25–30 h) [12].

Naratriptan

There are no data on its transfer into human milk. The few data on the safety of naratriptan during breastfeeding suggest it is safe, but, due to limited evidence, some caution is recommended (L3 Hale’s category) and alternative drugs are preferable [11, 12].

Rizatriptan

There are no data on its use during breastfeeding. In a study on rodents, the M/P ratio was 5, but some caution is recommended (L3 category) [11]. Until more is known about rizatriptan, it should not be preferentially used in breastfeeding mothers [12].

Sumatriptan

Sumatriptan is used in the treatment of moderate and severe migraine attacks in adults and in off-label regimen in children and adolescents [35, 36]. Orally, it is therapeutically active within 10–60 min, and it peaks after 2 h. It is also available in injections and intranasal preparations, which decrease its time of onset. If given subcutaneously, infants received between 3.5 and 13.5 % of maternal dose through breast milk. Since its oral bioavailability is less than the subcutaneous one, it is expected that the amount ingested during breastfeeding would be smaller [34]. It is the only triptan with a significant amount of data in breastfeeding mothers. It produces low levels in maternal milk (6.1–22.7 μg/L) [37]. A study of five lactating women showed no adverse effects on breastfed children [33]. It is considered safe [38], and therefore it is the triptan of first choice during breastfeeding [39]. It has been suggested, in selected cases (such as in the mother of a preterm infant), to wait 8 h after a single subcutaneous injection before breastfeeding [12]. Sumatriptan is classified as L3 [11].

Beta blockers

Beta blockers were initially reserved for the treatment of angina and hypertension but they are now frequently used as the initial drug for migraine prophylaxis. Beta blockers with proven efficacy in migraine prophylaxis include atenolol, metoprolol, nadolol, and propranolol.

Atenolol

Atenolol is found at higher concentrations in maternal milk than in plasma but its breast milk levels are low (<2 mg/L) [40–42]. It is estimated that breastfed infants receive between 5.7 and 19.2 % of the maternal weight-adjusted dosage of atenolol [9]. In the majority of nursing infants, plasma concentration of atenolol was too low (<10 ng/mL) to be clinically relevant [43]. Nonetheless, symptoms of beta blockade including hypotension, bradycardia, cyanosis, hypothermia, and lethargy have been reported in one breastfed infant [44]. Moreover, in nursing infants with inadequate renal function (preterm newborns or infants younger than 3 months or with kidney disease) or in case of high maternal dosage, symptoms of beta blockade may be even more frequent and eventually LactMed advises to prefer other beta blockers [12]. Because Tmax is unpredictable, timing feedings to avoid ingestion of the drug with maternal milk are not useful [12]. In summary, although it is considered as L3 [11], atenolol is not recommended during breastfeeding [33].

Metoprolol

It binds poorly to plasma proteins and has relatively high M/P. Nevertheless, its reported levels in milk are very low and its estimated RID is 1.4 % (L2 category) [11]. Metoprolol poses little risk to a breastfeeding infant [12, 45, 46].

Nadolol

Nadolol exemplifies how different bibliographic sources give conflicting advice on its use during breastfeeding. This beta blocker has an adult half-life of 20–24 h, it is only 30 % bound to plasma proteins, and it has a limited oral bioavailability (20–40 %). Its reported RID ranges from 4.4 to 6.9 % [11]. Its use is permitted during breastfeeding according to the American Academy of Pediatrics [38] while it is considered “possibly hazardous” by Hale (L4 category) [11] because of its long half-life and ability to concentrate in maternal milk (milk/plasma ratio = 4.6) [46]. LactMed recommends caution in using nadolol during breastfeeding [12]. Taken together, published data demonstrate a wide meta-variability of advice [47, 48]. Due to the relatively extensive excretion into breast milk, we hence decided to classify it as contraindicated and we recommend the use of other beta blockers during breastfeeding, especially in preterm infants (propanolol and metoprolol).

Propranolol

Propranolol is the first choice beta blocker during breastfeeding because of its elevated plasma protein binding, very low levels in milk, and its absence of side effects in the breastfed infants [40, 49]. Therefore, it can be considered safe for breastfeeding mothers (Hale’s L2) [11, 33].

Calcium channel antagonists

Cinnarizine

This piperazine derivative acts as a calcium channel blocker. In children, it may cause dizziness, epigastralgia, weight gain, and somnolence [50]. Cinnarizine intoxication was reported in a 30-month-old toddler and was accompanied by altered state of consciousness and convulsions [51]. Although Hale includes cinnarizine among L3 drugs [11], it use should be better avoided, as there are no data on its safety during breastfeeding. Cinnarizine is not reviewed by LactMed.

Flunarizine

There are no data on its use during breastfeeding; however, owing to its extremely long half-life (19 days in children), the risk of its accumulation is high. It is classified by Hale potentially hazardous [11] and should be prescribed only in case of lack of therapeutical alternatives, with extreme caution and monitoring the infant closely for hypotension. Flunarizine is not reported in LactMed. Its use in the breastfeeding woman should be better avoided.

Verapamil

When used at normal doses (240–360 mg/daily) in breastfeeding mothers, its levels in human milk are reported to be very low (<0.3 mg/L). Verapamil has been found in the serum of only one 5-day-old infant, while in other breastfed infants, it was not detectable [52–54]. Its RID is low, ranging from 0.15 to 0.2 %. No side effects in breastfed infants have been reported, especially after the first 2 months of life [12], although there may be a potential risk of hypotension, bradycardia, and peripheral edema. The clinical importance of verapamil-induced hyperprolactinemia and galactorrhea remains to be elucidated [54, 55]. Verapamil is rated as L2 by Hale [11].

Anticonvulsants

We have recently reviewed the use of antiepileptic drugs during breastfeeding [56]. Below, we report the information of the two anticonvulsants most frequently used for migraine attacks [56].

Topiramate

It is rapidly absorbed, it has a low plasma protein binding, a relatively long half-life, and a significant excretion into breast milk (M/P, 0.86) [11, 57] with a high RID (24.5 %) [11]. Despite these characteristics may raise some concerns on its use during breastfeeding, breastfed infants have very low serum levels (<2.8 μmol/L) in the first 3 months of life after maternal intakes of 150–200 mg/day of topiramate in association with carbamazepine (CBZ) [57]. These low serum levels seem to depend on the infant’s ability to eliminate topiramate, possibly facilitated by CBZ enzyme induction [57]. Moreover, infants who were breastfed by mothers treated with topiramate did not show side effects. Notwithstanding, their plasma level should be monitored [57, 58]. However, we are aware that there is no clear agreement on when to test them. We believe that 4 to 8 weeks is a reasonable time window, as, if the child is fully breastfed, breast milk would have reached its highest production and the consequent intake by the nursing infant would be at the maximum. Topiramate is rated by Hale as a L3 drug [11]. LactMed advises to monitor infants for diarrhea, somnolence, adequate weight gain, and psychomotor development, especially in younger, exclusively breastfed infants [12].

Valproic acid

Patients taking valproate may develop hepatotoxicity, thrombocytopenia, and anemia [59]. The limited passage of valproate into breast milk (the drug is almost completely bound to plasma proteins) would make it safe during lactation [60–63]. Serum levels in breastfed infants in fact are low [64]. However, there are some controversies on its safety profile. The teratogenic effect of valproate exposure in pregnancy [65], together with the decrease of methylation in the DNA extracted from the umbilical cord blood [66], induces a cautious use of this anticonvulsant during breastfeeding. A case report of a breastfed infant with thrombocytopenia, purpura, and anemia suggests to monitor the nursed infant for unusual bruising or bleeding [12, 67]. Hales rates valproic acid as L3 [11]. Although there is no clear indication to perform routine laboratory investigations, in case of late jaundice, it is reasonable to assess the hepatobiliary function and to test its plasma levels in the breastfed infant [12, 60, 65–70].

Antidepressants

Amitriptyline

Amitriptyline is poorly excreted in maternal milk and it is found at low concentrations in the plasma and urine of breastfed children [71]. No adverse side effects have been reported. It can be therefore considered safe (Hale’s L2) [11, 72–74]. LactMed suggests to prefer other drugs with fewer active metabolites, when large doses are required or while nursing a newborn or preterm infant [12].

Escitalopram

Escitalopram levels in breast milk are low or largely undetectable and it is well tolerated by breastfed infants (Hale’s L2) [11]. Lactmed recommends to monitor the infant for drowsiness if the infant is younger than 2 months, if he/she is exclusively breastfed, or if escitalopram is used in association with other psychotropic drugs [12, 73].

Paroxetine

Levels of paroxetine in breast milk are low and they have not been detected in the serum of most breastfed infants tested. Occasional mild side effects (irritability, eating and sleep disorders) have been reported especially when paroxetine was taken during the third trimester of pregnancy [12, 73]. However, paroxetine is an L2 drug [11] and is one of the preferred antidepressants during breastfeeding [12].

Sertraline

The transfer of sertraline to the breastfed infant is minimal and no significant adverse events have been reported. Sertraline is considered one of the antidepressants of choice during breastfeeding (Hale’s L2) [11, 12, 73].

Venlafaxine

Breastfed infants of mothers taking this drug, especially if newborn or preterm, should be monitored for excessive sedation and adequate weight gain [12]. To rule out its toxicity, measurement of serum desvenlafaxine is recommended in the breastfed infant [12]. Newborns of mothers who took the drug during pregnancy may experience neonatal abstinence syndrome. Hence, the use of venlafaxine during breastfeeding has been suggested in order to mitigate its withdrawal symptoms [12, 73]. It is classified as L3 [11].

Other drugs

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is considered safe during breastfeeding [19, 75] and it is the drug of choice for treating fever in breastfeeding mothers (Hale’s L1) [11, 12, 26]. In fact, according to studies carried out in the 1980s, its concentration in maternal milk ranges from 0.63 to 2.25 mg/kg/day [76, 77], lower than the doses normally administered intravenously in premature infants (10–15 mg/kg) [78]. Although multiple intravenous doses may cause hypotension in the newborn [79], the risk for the nursing infant appears negligible. We just found one report of a maculopapular rash on a 2-month-old infant, which was attributed to acetaminophen in breast milk [80].

Caffeine

Many over-the-counter analgesics contain caffeine. This xanthine has a stimulating effect on the central nervous system, and it is present in a vast range of beverages and foods. It appears in maternal milk about 1 h after oral ingestion [81, 82] and reach levels up to 15 mg/dL after major consumption of foods and beverages containing caffeine [81, 83, 84]. Theoretically, oral absorption by the nursing infant is good, although caffeine is not found in infant urine between 2 and 7 h after maternal ingestion [81]. Nursing children whose mothers consume caffeine-rich beverages have been noted to show agitation, sleep disturbance, and irritability [83, 85]. As a drug, caffeine has a good safety profile and it is used in the treatment and prevention of apnea in preterm infants (dose, 5–20 mg/kg/die) [85]. In preterm infants, it has a half-life of approximately 4 days, and in infants between 3 and 5 months of life, it can reach the adult half-life of 4–5 h [86]. Caffeine is considered compatible with breastfeeding (L2) [11, 38]. Nevertheless, a cohort study of mothers’ caffeine intake and its effect on nighttime awakening suggested that a daily limit of 300 mg of caffeine is reasonable; consequently, caffeine use by mothers should be generally restricted [12, 87–89].

Cyproheptadine

This antihistamine and serotonin agonist is used in the prophylaxis of vascular headache [90]. During breastfeeding, it should be used with caution because of its half-life (16 h), good intestinal absorption, and lack of data on its excretion in maternal milk (Hale’s L3) [11]. Owing to its serotonin receptor agonist effect, it is intended to lower prolactin production during treatment of amenorrhea-galactorrhea syndrome [91]. Cyproheptadine should be avoided in the nursing mother as it probably interferes with lactation [12] and its possible side effects on the breastfed infant include irritability and colic [31].

Ergotamine

It is an alkaloid produced by the ergot fungus; it exerts a vasoconstrictor action and it is found in medications for the treatment of acute migraine attacks, often in combination with caffeine. While it was commonly used in the past, it is now replaced by triptans. Its use should be considered contraindicated during breastfeeding (Hale’s L4) [11, 12, 89, 92] for two main reason. Firstly, it was found to cause vomiting and diarrhea by an old study dating from the 1930s, although these effects have not been substantiated [93]. Secondly, it can inhibit prolactin production and consequently lactation [94]. This latter was not, however, confirmed by Jolviet who reported that breastfed infants, whose mothers were taking ergotamine, ingested the same amount of maternal milk as the controls [93]. The level of ergotamine excreted in maternal milk is unknown.

Methysergide

It is a semisynthetic alkaloid ergot derivative, and it is rarely used as a migraine medication. It is administered only on an inpatient basis because of its major adverse events (retroperitoneal and heart valve fibrosis). There are no data on its use during breastfeeding, and being an ergot, it could potentially reduce plasma prolactin levels in mothers. Its use in breastfeeding women is contraindicated [95]. Neither Hale nor LactMed reviewed methysergide.

Metoclopramide

This antiemetic has been used in the treatment of acute migraine headache attacks by oral [96] and IV administration [97]. Its side effects include diarrhea, gastric disturbances, extrapyramidal symptoms, depression, and prolactin-induced galactorrhea. This last side effect has been exploited to induce lactation [98, 99], especially in mothers of preterm infants, without causing particular adverse effects on the child [100], and with no relevant differences compared to domperidone [98]. Metoclopramide is excreted in maternal milk with a RID ranging from 4.7 to 14.3 %, but intake by the infant is subclinical [101]. Although it is considered compatible with breastfeeding (L2 by Hale) [11], LactMed warns against using metoclopramide as galactogogue in women with a history of major depression [12].

Pizotifen

This antihistamine and serotonin receptor antagonist is structurally similar to tricyclic antidepressants and it is used in migraine prophylaxis in children [102, 103]. Though usually well tolerated, secondary effects such as somnolence, increased appetite, and weight gain have been reported in adults [104]. No studies on pizotifen therapy have been conducted in breastfeeding women. Hale and LactMed did not review pizotifen. The drug manufacturer advises to avoid its use during breastfeeding [95].

Discussion

Human milk provides the most complete form of nutrition for infants and carry beneficial effects on mothers [105] http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595230_eng.pdf. Nevertheless, on the basis of a case-by-case assessment, there are rare exceptions, when human milk is not recommended [http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/BFHI_2009_s1.pdf]. These exceptions include some medications used by the mother and possibly some AMDs. Doctors are often asked to give an opinion on the infant safety profile of medications taken by the breastfeeding mother. Available information are often scarce or non exhaustive and meta-variability of advice among different reference sources may further complicate the assessment [48].

As breastfeeding migraineurs mothers taking AMDs may be concerned about their baby’s health, and professional dilemmas may be encountered by physicians, we have completed the present review in order to facilitate the consultancy on the use of AMDs during breastfeeding.

We found that many AMDs can be safely used during breastfeeding and we have classified migraine medications according to their lactation risk profile into three groups:

-

1.

AMDs safe during lactation are as follows: low-dose ASA, ibuprofen, sumatriptan, metoprolol, propranolol, verapamil, amitriptyline, escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, acetaminophen, caffeine, and metoclopramide.

-

2.

AMDs moderately safe during lactation are as follows: diclofenac, ketoprofen, naproxen, most new triptans, topiramate, valproate, venlafaxine, and cyproheptadine.

-

3.

AMDs contraindicated during lactation are as follows: high-dose ASA, atenolol, nadolol, cinnarizine, flunarizine, ergotamine, methysergide, and pizotifen.

Our review is, however, not without limitations. The existing reports on the lactation risks of drugs in general [106] and of AMDs [5] are mostly anecdotal or based on case series and therefore of poor methodological quality. Moreover, any recorded side effect, while biologically and pharmacologically plausible in the nursing infant, is rarely attributable with certainty to a particular drug taken by her/his mother [107].

Consequently, although we took into account the most updated and authoritative sources (Hale and LactMed) on the use of drugs during breastfeeding, our approach in formulating the lactation risk for AMDs has been precautionary and, we are aware, somehow arbitrary.

Although most drugs transfer into human milk, most do so in subclinical amounts and, in principle, it is often (but not always) safe to breastfeed while using a medication. Consequently, evaluating the lactation risk of any drug has become a common and rather complex task for health professionals and should take into account several aspects.

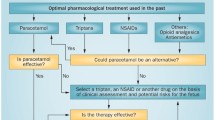

In order to treat migraine in breastfeeding women, drug choice should fall primarily on the medication found to be the most effective for the patient, evaluating the extent to which that drug enters milk and subsequently could affect the nursing infant.

When assessing AMD lactation risk, we should also consider the nursed infant age and the estimated total volume of breast milk consumed. A lower age, especially the first 2 months, implies a higher lactation risk for the nursed infant due to a reduced drug clearance. Moreover, an exclusively breastfed infant has a higher lactation risk than a partially weaned infant as the total amount of breast milk assumed is limited.

Regardless of whether a medication has been deemed safe, the breastfeeding woman should be better advised to take her AMD after feeding her infant, in order to minimize the amount of drug the child ingests with maternal milk.

Breastfeeding mothers need to be informed about the most common side effects of their migraine medications, in order to be able to promptly recognize them in their infants. Even if an AMD can be safely taken during lactation, it is a good clinical practice to call the mother’s attention on the behavior, sleep, feeding patterns, and growth of the nursing infant, especially in the first 2 months of life [79].

Finally, when indicated and feasible, we should recommend to monitor the infant AMD plasma levels.

Conclusions

According to our review, the majority of the revised AMDs were assessed to be compatible with breastfeeding. In most cases, migraineurs mothers can be advised to continue breastfeeding their babies safely, while treating their migraine attacks. In fact, only rarely there is a conflict of interest between keeping maternal and infant health.

References

Manzoni GC, Stovner LJ (2010). Epidemiology of headache. Handbook of clinical neurology 97:3–22

Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H et al (2013) The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache 53(3):427–436

Kvisvik EV, Stovner LJ, Helde G et al (2011) Headache and migraine during pregnancy and puerperium: the MIGRA-study. J Headache Pains 12(4):443–451

Hoshiyama E, Tatsumoto M, Iwanami H et al (2012) Postpartum migraines: a long-term prospective study. Intern Med 51(22):3119–3123

Hutchinson S, Marmuta MJ, Calhoun A et al (2013) Use of common migraine treatments in breastfeeding women: a summary of recommendations. Headache 53(4):614–627

Antonaci F, Dumitrache C, De Cillis I et al (2010) A review of current European treatment guidelines for migraine. J Headache Pain 11:13–19

Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F et al (2012) Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 78(17):1337–1345

Holland S, Silberstein SD, Freitag F et al (2012) Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Evidence-based guideline update: NSAIDs and other complementary treatments for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 78(17):1346–1353

Atkinson HC, Begg EJ, Darlow BA (1988) Drugs in human milk. Clinical pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinets 14:217–240

Bennett PN (1996) Drugs and human lactation. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Hale TW (2012) Medication and mothers’ milk. Hale Publishing, Amarillo

Voelker M, Hammer M (2012) Dissolution and pharmacokinetics of a novel micronized aspirin formulation. Inflammopharmacology 20(4):225–231

Unsworth J, D’Assis Fonseca A, Beswick DT (1987) Serum salicylate levels in a breast fed infants. Annals Rheum Diseases 46:638–639

Bailey DN, Weibert RT, Naylor AJ et al (1982) A study of salicylate and caffeine excretion in the breast milk of two nursing mothers. J Anal Toxicol 6:64–68

Terragna A, Spirito L (1967) Thrombocytopenic purpura in an infant after administration of acetylsalicylic acid to the wet-nurse. Minerva Pediatr 19(13):613–616

Clark JH, Wilson WG (1981) A 16-day-old breast-fed infant with metabolic acidosis caused by salicylate. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 20(1):53–54

Bell AD, Roussin A, Cartier R et al (2011) The use of antiplatelet therapy in the outpatient setting: Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines Executive Summary. Can J Cardiol 27(2):208–221

Spigset O, Hagg S (2000) Analgesics and breast-feeding: safety considerations. Paediatr drugs 2(3):223–238

Hirose M, Hara Y, Hosokawa T et al (1996) The effect of postoperative analgesia with continuous epidural bupivacaine after cesarean section on the amount of breast feeding and infant weight gain. Anesth Analg 82:1166–1169

Needs CJ, Brooks PM (1985) Antiirheumatic medication during lactation. Br J Rheumatol 24(3):291–297

Townsend RJ, Benedetti TJ, Erickson SH et al (1984) Excretion of ibuprofen into breast milk. Am J Obstet Gynecol 149:184–186

Perrott DA, Piira T, Goodenough B et al (2004) Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen vs ibuprofen for treating children’s pain or fever: a meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 158(6):521–526

Aranda JV, Thomas R (2006) Systematic review: intravenous ibuprofen in preterm newborns. Semin Perinatol 30:114–120

Ohlsson A, Walia R, Shah SS (2010). Ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm and/or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD003481

Davanzo R (2005) Farmaci ed allattamento al seno. In: Farmaci e gravidanza. La valutazione del rischio basata su prove di efficacia. Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) Ministero della Salute Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.A. Roma

Jacqz-Aigrain E, Serreau R, Boissinot C et al (2007) Excretion of ketoprofen and nalbuphine in human milk during treatment of maternal pain after delivery. Ther Drug Monit 29(6):815–818

Risser A, Donovan D, Heintzman J et al (2009) NSAID prescribing precautions. Am Fam Physician 80:1371–1378

Jamali F, Stevens DR (1983) Naproxen excretion in milk and its uptake by the infant. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 17:910–911

Fidalgo I, Correa R, Gomez Carrasco JA et al (1989) Acute anemia, rectorrhagia and hematuria caused by ingestion of naproxen. An Esp Pediatr 30:317–319

Ito S, Blajchman A, Stephenson M et al (1993) Prospective follow-up of adverse reactions in breast-fed infants exposed to maternal medication. Am J Obstet Gynecol 168:1393–1399

Goadsby PJ, Goldberg J, Silberstein SD (2008) Migraine in pregnancy. Br Med J 336:1502–1504

Silberstein SD, Goadsby PJ (2002) Migraine: preventive treatment. Cephalalgia 22(7):491–512

Duong S, Bozzo P, Nordeng H et al (2010) Safety of triptans for migraine headaches during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Can Fam Physician 56:537–539

Eiland LS, Hunt MO (2010) The use of triptans for pediatric migraines. Paediatr Drugs 12:379–389

O’Brien HL, Kabbouche MA, Hershey AD (2010) Treatment of acute migraine in the pediatric population. Curr Treat Options Neurol 12(3):178–185

Wojnar-Horton RE, Hackett LP, Yapp P et al (1996) Distribution and excretion of sumatriptan in human milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 41:217–221

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs (2001) The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 108(3):776–789

Jurgens TP, Schaefer C, May A (2009) Treatment of cluster headache in pregnancy and lactation. Cephalalgia 29(4):391–400

Thorley KJ, McAinsh J (1983) Levels of the beta-blockers atenolol and propranolol in the breast milk of women treated for hypertension in pregnancy. Biopharm Drug Dispos 4(3):299–301

Liedholm H, Melander A, Bitzen PO et al (1981) Accumulation of atenolol and metoprolol in human breast milk. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 20:229–231

White WB, Andreoli JW, Wong SH et al (1984) Atenolol in human plasma and breast milk. Obstet Gynecol 63(3 Suppl):42S–44S

Eyal S, Kim JD, Anderson GD et al (2010) Atenolol pharmacokinetics and excretion in breast milk during the first 6 to 8 months postpartum. J Clin Pharmacol 50:1301–1309

Schimmel MS, Eidelman AI, Wilschanski MA et al (1989) Toxic effects of atenolol consumed during breast feeding. J Pediatr 114:476–478

Sandstrom B, Regardh CG (1980) Metoprolol excretion into breast milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 9(5):518–519

Kulas J, Lunell NO, Rosing U et al (1984) Atenolol and metoprolol. A comparison of their excretion into human breast milk. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 118:65–69

Devlin RG, Duchin KL, Fleiss PM (1981) Nadolol in human serum and breast milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 12:393–396

Davanzo R, Rubert L, Oretti C (2008) Meta-variability of advice on drugs in the breastfeeding mother: the example of beta-blockers. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93:249–250

Anderson PO (1979) Propranolol in breast milk. Am J Psychiatry 136:466

Tosoni C, Lodi-Rizzini F, Bettoni L et al (2003) Cinnarizine is a useful and well-tolerated drug in the treatment of acquired cold urticaria (ACU). Eur J Dermatol 13:54–56

Turner D, Lurie Y, Finkelstein Y et al (2006) Pediatric cinnarizine overdose and toxicokinetics. Pediatrics 117:1067–1069

Andersen HJ (1983) Excretion of verapamil in human milk. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 25:279–280

Anderson P, Bondesson U, Mattiasson I et al (1987) Verapamil and norverapamil in plasma and breast milk during breast feeding. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 31:625–627

Gluskin LE, Strasberg B, Shah JH (1981) Verapamil-induced hyperprolactinemia and galactorrhea. Ann Intern Med 95:66–67

Fearrington EL, Rand CH, Rose JD (1983) Hyperprolactinemia-galactorrhea induced by verapamil. Am J Cardiol 51:1466–1467

Davanzo R, Dal Bo S, Bua J et al (2013) Antiepileptic drugs and breastfeeding. Ital J Pediatr 39:50

Ohman I, Vitols S, Luef G et al (2002) Topiramate kinetics during delivery, lactation, and in the neonate: preliminary observations. Epilepsia 43(10):1157–1160

Gentile S (2009) Topiramate in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Clin Drug Investig 29(2):139–141

Wyllie E, Wyllie R (1991) Routine laboratory monitoring for serious adverse effects of antiepileptic medications: the controversy. Epilepsia 32(Suppl 5):S74–S79

Chaudron LH, Jefferson JW (2000) Mood stabilizers during breastfeeding: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 61(2):79–90

Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N et al (2010) NEAD Study Group. Effects of breastfeeding in children of women taking antiepileptic drugs. Neurology 75(22):1954–1960

Bar-Oz B, Nulman I, Koren G et al (2000) Anticonvulsants and breast feeding: a critical review. Paediatr Drugs 2:113–126

Hagg S, Spigset O (2000) Anticonvulsant use during lactation. Drug Saf 22:425–440

Wisner KL, Perel J (1998) Serum levels of valproate and carbamazepine in breastfeeding mother-infant pairs. J Clin Psychopharmacol 18(2):167–169

Orny A (2009) Valporic acid in pregnancy: how much are we endangering the embryo and fetus? Reprod Toxicol 28(1):1–10

Smith AK, Conneely KN, Newport DJ et al (2012) Prenatal antiepileptic exposure associates with neonatal DNA methylation differences. Epigenetics 7(5):458–463

Stahl MM, Neiderud J, Vinge E (1997) Thrombocytopenic purpura and anemia in a breast-fed infant whose mother was treated with valproic acid. J Pediatr 130:1001–1003

Wallace SJ (1996) A comparative review of the adverse effects of anticonvulsants in children with epilepsy. Drug Saf 15(6):378–393

Perucca E (2002) Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of valproate: a summary after 35 years of clinical experience. CNS Drugs 16(10):695–714

Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Opjordsmoen S (2006) Use of psychotropic medications in treating mood disorders during lactation: practical recommendations. CNS Drugs 20(3):187–198

Yoshida K, Smith B, Craggs M et al (1997) Investigation of pharmacokinetics and of possible adverse effects in infants exposed to tricyclic antidepressants in breast-milk. J Affect Disord 43:225–237

Wisner KL, Perel JM, Findling RL (1996) Antidepressant treatment during breast-feeding. Am J Psychiatry 153:1132–1137

Davanzo R, Copertino M, De Cunto A et al (2011) Antidepressant drugs and breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed Med 6:89–98

Nielsen RE, Damkier P (2012) Pharmacological treatment of unipolar depression during pregnancy and breast-feeding—a clinical overview. Nord J Psychiatry 66(3):159–166

Bar-Oz B, Bulkowstein M, Benyamini L et al (2003) Use of antibiotic and analgesic drugs during lactation. Drug Saf 26:925–935

Berlin CM Jr, Yaffe SJ, Ragni M (1980) Disposition of acetaminophen in milk, saliva, and plasma of lactating women. Pediatr Pharmacol (New York) 1(2):135–141

Notarianni LJ, Oldham HG, Bennett PN (1987) Passage of paracetamol into breast milk and its subsequent metabolism by the neonate. Br J Clin Pharmacol 24:63–67

Palmer GM, Atkins M, Anderson BJ et al (2008) I.V. acetaminophen pharmacokinetics in neonates after multiple doses. Br J Anaesth 101:523–530

Allegaert K, Naulaers G (2010) Haemodynamics of intravenous paracetamol in neonates. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 66:855–858

Matheson I, Lunde PKM, Notarianni L (1985) Infant rash caused by paracetamol in breast milk? Pediatrics 76:651–652, Letter

Berlin CM, Denson HM, Daniel CH et al (1984) Disposition of dietary caffeine in milk, saliva, and plasma of lactating women. Pediatrics 73:59–63

Stavchansky S, Combs A, Sagraves R et al (1988) Pharmacokinetics of caffeine in breast milk and plasma after single oral administration of caffeine to lactating mothers. Biopharm Drug Dispos 9:285–299

Ryu JE (1985) Effect of maternal caffeine consumption on heart rate and sleep time of breast-fed infants. Dev Pharmacol Ther 8:355–363

Tyrala EE, Dodson WE (1979) Caffeine secretion into breast milk. Arch Dis Child 54:787–800

Gray PH, Flenady VJ, Charles BG et al (2011) Caffeine citrate for very preterm infants: effects on development, temperament and behaviour. J Paediatr Child Health 47:167–172

McNamara PJ, Abbassi M (2004) Neonatal exposure to drugs in breast milk. Pharm Res 21:555–566

Liston J (1998) Breastfeeding and the use of recreational drugs–alcohol, caffeine, nicotine and marijuana. Breastfeed Rev 6:27–30

Santos IS, Matijasevich A, Domingues MR (2012) Maternal caffeine consumption and infant nighttime waking: prospective cohort study. Pediatrics 129:860–868

Moretti ME, Lee A, Ito S (2000) Which drugs are contraindicated during breastfeeding? Practice guidelines. Can Fam Physician 46:1753–1757

Mahachoklertwattana P, Wanasuwankul S, Poomthavorn P et al (2009) Short-term cyproheptadine therapy in underweight children: effects on growth and serum insulin-like growth factor-I. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 22:425–432

Wortsman J, Soler NG, Hirschowitz J (1979) Cyproheptadine in the management of the galactorrhea-amenorrhea syndrome. Ann Intern Med 90:923–925

Fomina PI (1934) Untersuchungen uber den ubergang des aktiven Agens des Mutterkorns in die milch stillender Mutter. Arch Gynakol 157:275–285

Jolivet A, Robyn C, Huraux-Rendu C et al (1978) Effect of ergot alkaloid derivatives on milk secretion in the immediate postpartum period. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 7(1):129–134

Shane JM, Naftolin F (1974) Effect of ergonovine maleate on puerperal prolactin. Am J Obstet Gynecol 120:129–131

British National Formulary (BNF) (2010). British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, London

Azzopardi TD, Brooks NA (2008) Oral metoclopramide as an adjunct to analgesics for the outpatient treatment of acute migraine. Ann Pharmacother 42:397–402

Friedman BW, Mulvey L, Esses D et al (2011) Metoclopramide for acute migraine: a dose-finding randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med 57:475–482

Ingram J, Taylor H, Churchill C (2012) Metoclopramide or domperidone for increasing maternal breast milk output: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 97(4):F241–F245

Zuppa AA, Sindico P, Orchi C et al (2010) Safety and efficacy of galactogogues: substances that induce, maintain and increase breast milk production. J Pharm Pharm Sci 13:162–174

Ehrenkranz RA, Ackerman BA (1986) Metoclopramide effect on faltering milk production by mothers of premature infants. Pediatrics 78:614–620

Kauppila A, Arvela P, Koivisto M et al (1983) Metoclopramide and breast feeding: transfer into milk and the newborn. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 25:819–823

Barnes NP, James EK (2009). Migraine headache in children. Clin Evid (Online)

Silcocks P, Whitham D, Whitehouse WP (2010) P3MC: a double blind parallel group randomised placebo controlled trial of propranolol and pizotifen in preventing migraine in children. Trials 11:71

Briars GL, Travis SE, Anand B et al (2008) Weight gain with pizotifen therapy. Arch Dis Child 93(7):590–593

Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. (2007). Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). (153):1–186.

Schirm E, Schwagermann MP, Tobi H et al (2004) Drug use during breastfeeding. A survey from the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Nutr 58(2):386–390

Anderson A (2003) Breastfeeding: societal encouragement needed. J Hum Nutr Diet 16(4):217–218

Taketomo CK (2012–2013) Pediatric and neonatal dosage handbook. Lexi-Comp, Hudson, OH

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof Thomas Hale, Texas Tech University, School of Medicine, Amarillo, Texas, for helpful advice.

Conflict of interest

This study was performed without any funding or grants. All authors declare that they have no competing interest and do not have any financial relationships with any biotechnology and/or pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors’ contributions

RD: conception and design. All authors: collection, assembly and analysis and interpretation of the data. GP, GF, and RD: drafting of the article. RD and JB: critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors listed here have seen and approved the final version of the report.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davanzo, R., Bua, J., Paloni, G. et al. Breastfeeding and migraine drugs. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70, 1313–1324 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1748-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1748-0