Abstract

Purpose

Adherence to antidepressant therapy by patients with depressive disorders is essential not only to achieve a positive patient outcome but also to prevent a relapse. The aim of this study was to identify potential modelling factors influencing adherence to antidepressant treatment by patients with mood disorders in the community mental health care setting

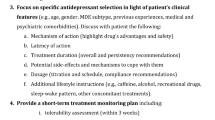

Methods

A total of 160 consecutive psychiatric outpatients attending two Community Mental Health Centres on Tenerife Island between September 2011 and May 2012 were asked to participate in the study; of these, 145 accepted. The Morisky self-report scale was used to assess adherence. The potential predictors examined included socio-demographic, clinical and therapeutic variables. The Clinical Global Impression-Severity and -Improvement scales and the Beck Depression Inventory were used for clinical assessment. Drug treatment side-effects were assessed using the “Self-report Antidepressant Side-Effect Checklist.” All participants were also asked to complete the "Drug Attitude Inventory" (DAI), "Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire" (BMQ), and "Leeds Attitude towards concordance Scale". Discriminant analyses were performed to predict non-adherence.

Results

There was no clear correlation between adherence and the socio-demographic variables examined, but adherence was related to a positive attitude of the patients towards his/her treatment (DAI) and low scores in the BMQ-Harm and -Concern subscales. Non-adherence was also related to an increasing severity of depression and to the presence and severity of side-effects.

Conclusions

Among our study cohort, the profiles of adherent patients to antidepressant treatment were more closely associated with each patient’s attitudes and beliefs than to objective socio-demographic variables. The severity of depression played a relevant role in adherence, but whether this role is direct or an interaction with several concurrent factors is not yet clear. Side-effects were also closely related to adherence, as conditioned by frequent polypharmacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depressive disorders have become a priority public health concern due to their high prevalence and global disease burden, mainly as a result of the disability caused to the individual. The total number of people with depression in Europe reached 21 million in 2004 [2], and the World Health Organization estimates that by 2020 depression will become the second most important cause of disability worldwide [53].

Since the 1960s, antidepressant drugs have relieved much human suffering and have become the most widely consumed drug family in the developed world. Although antidepressants were initially developed to treat depression, the utility of these drugs quickly expanded to include other conditions, and they are currently extensively used in psychiatric clinical practice [1, 20]. Many antidepressants also effectively treat anxiety disorders and have approved indications for the treatment of social phobia, post-traumatic stress, panic, obsessive–compulsive and general anxiety disorders. Antidepressants are also used to treat bulimia, the premenstrual dysphoric disorder and chronic pain associated with disorders such as diabetic and post-herpetic neuralgia [18].

Of course, medications will not work if patients refuse to take them. Research has shown that nearly 50 % of outpatients given an antidepressant discontinue medication treatment during the first month [11], and data indicate that as many as 68 % of patients discontinue treatment within the first 3 months, depending on the population and the specific antidepressant prescribed [9]. Adherence to antidepressant therapy in patients with depressive disorders is essential not only to achieve a positive patient outcome but also to prevent relapse [10]. A recent systematic review of the literature of observational studies on predictors of compliance with antidepressants prescribed for depressive disorders has shown the inconsistency of socio-demographic and clinical variables, including severity of depression, on predicting adherent behaviour and the role played by some comorbidities and substance abuse [42].

There is a clear need to identify determinants of non-adherence that could be addressed in interventions to facilitate optimal use of medicines. The aim of this study was to identify potential predictors of adherence to antidepressant treatment by patients with mood disorders in the community mental health care setting. We examined a wide range of potential predictors, including socio-demographic variables, clinical variables, such as severity of depression and adverse effects from medication used, beliefs and attitudes of psychiatric patients towards their prescribed treatment and attitudes towards partnership in medicine-taking.

Methods

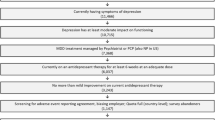

Sample

From September 2011 to May 2012, 160 consecutive psychiatric outpatients with mood disorders using antidepressants who were attending two Community Mental Health Centres at Tenerife Island (Canary Islands, Spain) were invited to participate in the study. Each participant received a full explanation of the study, after which he/she signed an informed consent document that had been approved by the local ethics committee. Each participant then filled out a brief socio-demographic survey and the other questionnaires.

Measures

Socio-demographic characteristics and clinical variables

Age, gender, educational level, history as a psychiatric patient (in years) and type of psychoactive drugs currently taken were assessed.

For evaluation purposes the drugs were divided into the common groups of psychotropics: antidepressants [tricyclics (N06AA); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (N06AB); serotonin and norepinephrine selective reuptake inhibitors (N06AX)]; benzodiazepines (N05BA); antipsychotics (N05A) (conventional and atypical); mood stabilizers [lithium (N05AN01); carbamazepine (N03AF01); valproate (N03AG01)]. We also recorded how long patients had been under their current psychiatric treatment (in months) and the number of different psychiatrists who have treated them during that time. The psychiatrist(s) responsible for the patient’s mental health care was asked about patient diagnosis and after consultation with the patient filled ind the Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI-S) and the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale (CGI-I) for that patient [23].

Self-reported adherence

Self-reported adherence to antidepressant medication was assessed using the Spanish version of the Morisky scale [36] which has been properly validated [50]. This is a simple four-item yes/no self-report instrument frequently used for assessing patient adherence to treatment across a variety of chronic medical and psychiatric conditions, including mood disorders [34, 46]. The Morisky scale includes items querying whether the patient ever forgot to take medications, was careless with medications, stopped taking medications when at times when feeling better or stopped taking medications when feeling worse. This scale allows patients to be classified as adherent or non-adherent. Patients are classified as non-adherent when they answer “yes” to at least one of the four questions. High adherence is defined as a “no” answer to every question. The scale has been shown to have moderate reliability (α = 0.62) and good concurrent and predictive validity in outpatient settings [35, 36].

Attitudes toward treatment

Drug Attitude Inventory

The Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI) [25] is a self-report scale developed to measure the subjective responses and attitudes of psychiatric patients towards their treatment by revealing whether the patients are satisfied with their medications and evaluating their understanding of how the treatment is affecting them. The original version of the scale consists of 30 items covering seven categories: subjective positive, subjective negative, health and illness, physician control, prevention and harm. A shorter, newer version consisting of ten key items has also been developed (DAI-10). This shorter version has ten highly specific items of subjective experience presented as self-report statements with which the patient agrees or disagrees. These are based on actual recorded and transcribed accounts of patients, and response options are true/false only. These items were selected for their capacity to discriminate between medication adherence levels in a way that can be analyzed statistically. Each response is scored as +1 if correct or −1 if incorrect. The final score is the grand total of the positive and negative points and ranges in value from −10 to 10, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude towards medication. A positive total score means a positive subjective response; a negative total score means a negative subjective response. The DAI-10 is concise and easy to administer, and its psychometric properties are well established. The scale has been shown to have test–retest reliability, high internal consistency and discriminant, predictive and concurrent validity [24]. Although the DAI was initially designed for schizophrenia, it has also been used to investigate treatment adherence in patients with mood disorders [51]. In our study, we used the Spanish version validated by García Cabeza et al. [19].

Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire

The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) was developed in the UK by Horne et al. [27] and validated for psychotropics into Spanish by De las Cuevas et al. [12, 13]. It comprises a general and a specific scale, and each scale has two subscales. The BMQ-General scale assesses more general beliefs or social representations of pharmaceuticals as a class of treatment and includes eight items in two subscales (four items each), namely, Overuse and Harm. The BMQ-Specific scale assesses patient’s beliefs about the medication he/she is prescribed for a specific illness in terms of the necessity and concern about taking it. This scale includes ten items in two subscales (5 items each), namely, Concern and Necessity. The degree of agreement with each statement is indicated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The BMQ has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure and to be able to discriminate between different groups of patients [5, 26, 33].

Leeds Attitude toward Concordance scale

The Leeds Attitude toward Concordance scale (LATCon) is a 12-item self-report scale developed by Raynor et al. [39] which assesses patients’ and health professionals’ attitudes towards concordance in medicine-taking. The respondent scores each item on a four-point Likert scale as strongly disagree (0), disagree (1), agree (2) or strongly agree (3), and the higher the score in the scale, the more positive the respondent's attitude towards concordance. To facilitate interpretation, the total score is divided by the number of items, leading to an average score per item. Raynor et al. [39] reported a reliability of 0.79 (Cronbach’s α). This instrument has been translated into Spanish and validated in psychiatric outpatients [12, 13], showing a monofactorial solution with good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

Self-report Antidepressant Side-Effect Checklist

The Antidepressant Side-Effect Checklist (ASEC) [49] is a self-report questionnaire that measures the presence and severity of 20 possible adverse reactions to antidepressants. For each item, the participants rated the severity of the specified symptom on a four-point scale (0, absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe) and specified whether a symptom (if present) was likely to be a side-effect of the antidepressant drug (yes or no). A space for comment is provided next to each item. Optional free-text entries provide the opportunity to list other complaints and explain the impact of adverse reactions. The original checklist was translated to Spanish using the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-reported measures as the methodological model for the Spanish translation. We defined three global indices to provide a means of communicating an individual’s side-effect profile with a single number, as follows:

-

1.

Global Adverse Reaction Severity Index (GARSI). This index was designed to measure overall side-effects and is probably the best single indicator of the current level of adverse reactions. GARSI shows the level of severity of side-effects and provides information on the number of adverse reactions and their severity since it is the average score of the 21 items of the questionnaire.

-

2.

Positive Side-Effect Distress Index (PSEDI). This index is a pure intensity measure since it is the average score of the items scored above zero. PSEDI probably also assesses the response style of the patient, i.e. whether the patient is “augmenting” or “attenuating” his/her adverse reactions.

-

3.

Positive Side-Effect, Total (PSET). This index simply measures the number of adverse reactions that are reported positive by the respondent, i.e. the number of items scored above zero.

Clinical status

Beck Depression Inventory

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses cognitive, behavioral, affective and somatic symptoms of depression. It has been developed to correspond to the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn.) criteria for depressive diagnoses [4]. Each item is scored by the subject on a four-point scale (0–3) according to the way the participant has been feeling in the previous 2 weeks. The 21 items are then summed to give a single total score for the BDI-II, for which cutoff scores have previously been established. The cutoffs used differ from the original: 0–13 indicates minimal depression; 14–19 indicates mild depression; 20–28 indicates moderate depression; 29–63 indicates severe depression. Higher total scores indicate more severe depression-related symptoms. The BDI-II is a reliable and well-validated measure when the aim is to screen for depression symptoms in adults, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.73 to 0.95. We used the Spanish version validated by Sanz et al. [45].

Data analysis

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed according to descriptive analyses. To contrast adherent and non-adherent patients in the different variables, we performed one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA). Finally, to predict adherence level we carried out a discriminant analysis to introduce together both nominal and continuous variables. A direct method was selected to identify the specific role of the different variables taken into account. These analyses were performed with SPSS ver. 19 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Of the 160 patients with mood disorders using antidepressants who were asked to participate in the study, 145 agreed, with is a high response rate of 90.6 %. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample according to the socio-demographic and clinical variables included in the study. Based on the Morisky Scale total scores, slightly more than half of the patients (78, 53.8 %) could be classified as adherent to the treatment prescribed.

To verify data on the self-report measures, we first analyzed mean differences (one-factor ANOVA) between adherent and non-adherent patients, who were categorized as such based on these self-report measures, , usually in association to treatment adherence. Table 2 presents the results of this analysis. Non-adherent patients were found to have significantly higher scores in the BMQ-Harm subscale, which assesses beliefs about the general harmfulness of psychiatric medicines, the BMQ-Concern subscale, which assesses the potential adverse effects of the patient’s prescribed treatment, such as dependence, side-effects, or accumulation effects, BDI-II, which assesses the severity of depression and GARSI, which provides information on the severity of the side-effects experienced, combining information on the number of adverse effects and their intensity. In contrast, based on the DAI scale, adherent patients were found to have a significantly higher positive attitude toward their medication.

We also carried out a statistical analysis in which we took into account the specific side-effects affecting the differences between complaint and non-compliant patients. Table 3 shows the prevalence of the different adverse reactions self-reported by the patients and the intensity of each secondary effect in those respondents experiencing them, both in the total sample and according to adherence. As can be seen in Table 3, dry mouth, insomnia (difficulty in sleeping), headache and weight gain were self-reported by more than one-half of the patients, and dry mouth, constipation, problems with sexual function, sweating and weight gain were the most severe adverse effects experienced by the patients.

According the ANOVA on the contrast between adherent and non-adherent patients, when individual side-effects were considered, adherent patients self-reported a higher frequency of dry mouth, drowsiness, problems with sexual function and tremor; the other adverse effects recorded were reported more frequently by non-adherent patients. Four side-effects were experienced with a significantly higher severity by non-adherent patients: dry mouth, diarrhoea and feeling like the room is spinning. On the other hand, weight gain was self-reported with a significantly higher severity by adherent patients.

A final analysis was carried out to determine the role of these self-reported measures in predicting treatment adherence, together with those socio-demographic variables traditionally associated with compliance. Since there were both nominal and continuous variables, a discriminant analysis (direct method) was performed as with this method we were able to identify the specific role of the different variables in the discriminant function. The variables introduced were gender (1 = male; 2 = female), age, educational level (1 = no formal education; 2 = primary studies; 3 = secondary studies; 4 = university degree), treatment duration (in months), the number of different psychiatrists, drug attitude (DAI-10), beliefs about medicines (both BMQ-Overuse and BMQ-Harm subecale scores), concordance (LATcon score), level of depression (BDI-II score), and CGI-S score. According to the Morisky scale, adherence patients were classified as compliant (0 value) and non-compliant (1 value). Since not all these variables met the criteria of normal distribution, the data must be interpreted with caution.

The discriminant function obtained reached a Wilks’ λ = 0.96, which is statistically relevant [X2(1) = 4.7; p = 0.03]. With this function, 62.8 % of patients were correctly classified. The function structure is summarized in Table 4.

We found four variables with coefficients that were ≥ 0.50. Concerns about the potential adverse consequences of their use as psychiatric drug treatment, the consideration of psychotropic drugs as harmful medicines, the severity of depression and the level of severity of side-effects of drugs used were more related to non-compliant patients. A second group of variables were the subjective responses and attitudes of psychiatric outpatients with mood disorders towards their treatment, the educational level and variables reported positive by the patient. In these cases, whereas a positive attitude to a drug and a higher level of education were related to higher adherence, the number of adverse reactions was related to non-adherence. The remaining variables played a relatively minor role in predicting adherence. In this case, the low coefficients of the variables number of different drugs used, patients’ age and patients’ gender are remarkable.

Discussion

Until about two decades ago, depression was considered to be an episodic disease. However, results from long-term naturalistic research studies have shown that depression is a lifelong disease, with a high tendency to recur, as found in 85 % of patients diagnosed with unipolar depression [28, 29]. Moreover, recurrence of depression, in turn, increases the likelihood that future episodes will be more severe, more frequent and more difficult to treat [31].

Although the long-term efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressants among real-world patients have been questioned [21], it is accepted that antidepressants can be efficacious for some patients by reducing depressive symptoms and preventing the risk of relapse [22, 32, 40, 41]. Therefore, antidepressant adherence in patients with depressive disorders is essential not only to facilitate a positive patient outcome but also to prevent relapse.

Adherence to prescribed psychotropic medication is relevant provided that the diagnosis of the mood disorders is well established and the indication for the prescription of the drug treatment is adequate. In these cases, treatment effectiveness is hampered by the lack of adherence to the prescribed regimen. Multiple co-prescription of psychotropics is common and a debatable practice [14, 15]. The concomitant use of psychiatric drugs is likely based more on experience than evidence [47] and is still hampered by a lack of systematic research and possibly by the pressures of the pharmaceutical industry [15]. Concerns with polypharmacy include the possibility of cumulative toxicity [38] and increased vulnerability to adverse events [48], as well as adherence issues that emerge with increasing regimen complexity [37]. Taken as a whole, patients and clinicians alike are facing more complicated treatment regimens that are not supported by solid scientific evidence and which aremore difficult to follow by the patient—with the additional problem of a higher probability of side-effects. The development of side-effects is one of the most commonly associated issues with the lack of adherence [3, 6, 30], and premature discontinuation of medication is usually associated with a poorer outcome in the treatment of mood disorders [7]. However, adherence, simplicity and efficacy usually go together.

There is an ample body of knowledge published on which factors could be the most important in determining poor adherence. According to one of the latest systematic reviews [42], there is no evidence of a substantial relationship between compliance with the medication ordered and socio-demographic factors such as age, race, educational level, socio-economic level or even gender. This review also reports that the severity of depression or co-morbidity also seems not to be closely related to adherence, whereas the use of illicit drugs might reduce the compliance

If there is no a clear socio-demographic or clinical profile that will help to identify the non-adherent patient, which other factors might be at works? What does our study add to knowledge already available?

Drug treatment side-effects

It is difficult to link the presence of side-effects with the patient’s adherence to the treatment. In fact, as Table 3 shows, those patients taking the medication (adherence) present frequent side-effects, most of which are clearly related to the pharmacological action of the drugs (dry mouth, diarrhea, feeling like the room is spinning, weight gain). Surprisingly enough, the non-adherent patients in our study cohort described more frequent and more intense side-effects than adherent patients. This experience was not directed related to the adequate intake of the treatment (because they were non-adherent) but with the perception of side-effects by these patients. In this context it is difficult to distinguish cause and effect.

Beliefs and attitudes

In our analysis, the measurement of adherence correlated with a higher DAI total score and lower scores for theBMQ subscales for perceived Harm and Concern (see Table 2) but it did not correlate with the subscales on Overuse or Necessity. This might imply that the adherent behaviour is more related to personalities that have a more positive view of the benefits of drugs, rather than non-adherence being related to an elevated perception of risks [16, 52]. The LATCon Scale showed no differences among adherent and non-adherent patients, but this scale is designed to analyze “concordance” which is an step beyond mere adherent behavior. Our results are in line with previous ones confirming that attitudes and beliefs about antidepressant medication predict adherence to treatment [8, 17, 44] .

Severity of depression

A relevant finding of our study is that adherence among our study cohort seemed to correlate well with the severity of depression. The depression of the adherent patients was less severe (BDI-II score: 18, mild) than that of non-adherent (BDI-II score: 22, moderate). However, it is unclear whether those patients who were more depressed were not taking the medication as prescribed because they were not inclined to accept the medication, or whether they were worse precisely because they were not taking the efficacious treatment. This ambiguity is in agreement with the systematic review performed by Rivero-Santana et al. [42], of the ten published studies examined in this review that assessed the influence of severity of depression, only those of Rusell et al. [44] and Roca et al. [43] found that the severity of depression was related to worse adherence. Rivero-Santana et al. [42] considered that the explanation of the only two cross-sectional studies which obtained statistically significant findings could be explained by an inverse causal association, i.e. that better adherence leads to improvements in the clinical course of the disease and that it is probably the course of symptoms, rather than the severity level at any moment of the treatment, which predicts non-adherence.

The results depicted in Table 4 may also throw light on the issue. The factors of the discriminant function that correlated with adherence are mainly scores and tests that explore the personal perception of the benefits and risks of drugs. Patients with low adherence were those with high scores on the BMQ-Concern (0.51) and BMQ-Harm (0.51) and who had severe depression (BDI-II: 0.51), whereas the other factors that correlated with low adherence were the DAI-10 (−0.47) and educational level (−0.43). The other set of factors that were significant in the discriminant function were mainly related to the presence of side effects.

In this way, a new profile of patients emerges when all of these scores are put together. This profile correlates the adherence to medication to a positive attitude towards medication and a higher cultural level and the lack of adherence to a higher personal perception of the risk and the presence of side-effects. As such, the results of our study may have clinical implications for health professionals treating mood disorders and provide a new vision of the factors that may influence adherence to medication. Most of the variables that have been studied in the literature (age, gender, socio-demographic characteristics, morbidity, among others) are not as important as the patient’s personal perception(s) of drugs. In addition, the variations in the way each individual perceives the value of drugs is the main factor that would influence their future adherence to the treatment. For these reasons, the debate should not be focused so much on the individual characteristics of the patients but on the perceptions and expectations of each patients towards the prescribed drug.

For whatever reason (scarcity of time, competing urgencies or perceived lack of importance, among others), mental health professionals do not often ask patients about their health beliefs concerning their condition, treatment efficacy or concerns about side-effects. When working with depressive patients physicians and psychiatrists need to work with the patient using a collaborative approach to “connect” and listen to the message the patient is sending and assist the patient in dealing with possibly overwhelming feelings related to the self-management of depressive disorders. Patients’ health beliefs and attitudes need to be assessed in order to improve adherence, and care and treatment must focus on the person through a partnership that facilitates the achievement of the greatest degree of positive depression outcomes. Depressive patients need to be assisted to internalize the degree of their susceptibility to the detrimental effects of their mood disorder and the benefits of adhering to the depression treatment regimen into their belief system.

References

Ables AZ, Baughman OL III (2003) Antidepressants: update on new agents and indications. Am Fam Physician 67:547–554

Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H et al (2004) Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 420:21–27

Baldessarini RJ, Perry R, Pike J (2008) Factors associated with treatment nonadherence among US bipolar disorder patients. Hum Psychopharmacol 23(2):95–105

Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W (1996) Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess 67(3):588–597

Beléndez M, Hernández A, Horne R, Weinman J (2007) Evaluación de las creencias sobre el tratamiento: Validez y fiabilidad de la versión española del Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire. Int J Health Clin Psychol 7:767–779

Blackwell B (1982) Antidepressant drugs: side effects and compliance. J Clin Psychiatry 43 (11 Pt 2):14–21

Bockting C, ten Doesschate MC, Spijker J, Spinhoven P, Koeter MW, Schene AH (2008) Continuation and maintenance use of antidepressants in recurrent depression. Psychother Psychosom 77(1):17–26

Brown C, Battista DR, Bruehlman R, Sereika SS, Thase ME, Dunbar-Jacob J (2005) Beliefs about antidepressant medications in primary care patients: relationship to self-reported adherence. Med Care 43(12):1203–1207

Bucci KK, Possidente CJ, Talbot KA (2003) Strategies to improve medication adherence in patients with depression. Am J Health Syst Pharm 60(24):2601–2605

Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM, Lee JY, Ming EE, Markson LE, Fireman B (2002) Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: influence of patient-physician communication. JAMA 288(11):1403–1409

Castle T, Cunningham MA, Marsh GM (2012) Antidepressant medication adherence via interactive voice response telephone calls. Am J Manage Care 18(9):e346–e355

De las Cuevas C, Rivero A, Perestelo-Perez L, Gonzalez M, Perez J, Peñate W (2011) Psychiatric patients’ attitudes towards concordance and shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 85:e245–e250

De las Cuevas C, Rivero-Santana A, Perestelo-Pérez L, González-Lorenzo M, Pérez-Ramos J, Sanz EJ (2011) Adaptation and validation study of the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire in psychiatric outpatients in a community mental health setting. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp 26:140–146

De las Cuevas C, Sanz EJ (2004) Polypharmacy In psychiatric practice in the Canary Islands. BMC Psychiatry 4:18

De las Cuevas C, Sanz EJ (2005) Polypsychopharmacy. A frequent and debatable practice in psychiatric inpatients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 25(5):510–512

Emilsson M, Berndtsson I, Lötvall J, Millqvist E, Lundgren J, Johansson A, Brink E (2011) The influence of personality traits and beliefs about medicines on adherence to asthma treatment. Prim Care Respir J 20(2):141–147

Fawzi W, Abdel Mohsen MY, Hashem AH, Moussa S, Coker E, Wilson KC (2012) Beliefs about medications predict adherence to antidepressants in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 24(1):159–169

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2012) Antidepressant use in children, adolescents, and adults. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM096273

García Cabeza I, Hormaechea Beldarrain JA, Mr SA, Arango López C, González de Chávez M (2000) Drug attitude inventory, spanish-adapted version. Euro Neuropsychopharm 10(3):298–299

Gardarsdottir H, Heerdink ER, van Dijk L, Egberts AC (2007) Indications for antidepressant drug prescribing in general practice in the Netherlands. J Affect Disord 98:109–115

Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, Thaler K, Lux L, Van Noord M, Mager U, Thieda P, Gaynes BN, Wilkins T, Strobelberger M, Lloyd S, Reichenpfader U, Lohr KN (2011) Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 155(11):772–785

Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, Furukawa TA, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Goodwin GM (2003) Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 361(9358):653–661

Guy W (1976) Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (ECDEU) Assessment manual for psychopharmacology. National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda

Hogan TP, Awad AG (1992) Subjective response to neuroleptics and outcome in schizophrenia: a re-examination comparing two measures. Psychol Med 22:347–352

Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R (1983) A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med 13:177–183

Horne R, Weinman J (1999) Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illnesss. J Psychosom Res 47:555–567

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M (1999) The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: The development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 14:1–24

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Keller MB (2003) A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:261–269

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB (2002) The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:530–537

Kelly K, Posternak M, Alpert JE (2008) Toward achieving optimal response: understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 10(4):409–418

Kessing LV, Hansen MG, Andersen PK (2004) Course of illness in depressive and bipolar disorders. Naturalistic study, 1994–1999. Br J Psychiatry 185:372–377

Levkovitz Y, Tedeschini E, Papakostas GI (2011) Efficacy of antidepressants for dysthymia: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry 72(4):509–514

Mahler C, Hermann K, Horne R, Jank S, Haefeli WE, Szecsenyi J (2012) Patients' beliefs about medicines in a primary care setting in Germany. J Eval Clin Pract 18(2):409–413

Miklowitz DJ, Simoneau TL, George EL, Richards JA, Kalbag A, Sachs-Ericsson N, Suddath R (2000) Family-focused treatment of bipolar disorder: 1-year effects of a psycho-educational program in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Biol Psychiatry 48:582–592

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ (2008) Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 10:348–354

Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM (1986) Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 24:67–74

Murray M, Kroenke K (2001) Polypharmacy and medication adherence: Small steps on a long road. J Gen Intern Med 16:137–139

Rascati K (1995) Drug utilization review of concomitant use of specific serotonine reuptake inhibitors or clomipramine and antianxiety/sleep medications. Clin Ther 17:786–790

Raynor DK, Thistlethwaite JE, Hart K, Knapp P (2001) Are health professionals ready for the new philosophy of concordance in medicine taking? Int J Pharm Pract 9:81–84

Reynolds CF, Butters MA, Lopez O, Pollock BG, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, Lenze EJ, Holm M, Rogers JC, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Begley A, Anderson S, Karp JF, Miller MD, Whyte EM, Stack J, Gildengers A, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kaufer DI, Kamboh MI, DeKosky ST (2011) Maintenance treatment of depression in old age: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the efficacy and safety of donepezil combined with antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68(1):51–60

Reynolds CF, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Frank E, Miller MD, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Butters MA, Stack JA, Schlernitzauer MA, Whyte EM, Gildengers A, Karp J, Lenze E, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kupfer DJ (2006) Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med 354(11):1130–1138

Rivero-Santana A, Perestelo-Perez L, Pérez-Ramos J, Serrano-Aguilar P, Cuevas CDl (2013) Sociodemographic and clinical predictors of compliance with antidepressants for depressive disorders. A systematic review of observational studies. Patient Prefer Adherence 7:151–169

Roca M, Armengol S, Monzón S, Salva J, Gili M (2011) Adherence to medication in depressive patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 31:541–543

Russell J, Kazantzis N (2008) Medication beliefs and adherence to antidepressants in primary care. N Z Med J 121(1286):14–20

Sanz J, García MP, Espinosa R, Fortún M, Vázquez C (2005) Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): 3. Propiedades psicométricas en pacientes con trastornos psicológicos. Clín Salud 16:121–142

Shalansky SJ, Levy AR, Ignaszewski AP (2004) Self-reported Morisky score for identifying nonadherence with cardiovascular medications. Ann Pharmacother 38:1363–1368

Stahl SM (2002) Antipsychotic polypharmacy: evidence based or eminence based? Acta Psychiatr Scand 106:321–322

Tanaka E, Hisawa S (1999) Clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with psychoactive drugs: antidepressants and antipsychotics and the cytochrome P450 system. J Clin Pharm Ther 24:7–16

Uher R, Farmer A, Henigsberg N, Rietschel M, Mors O, Maier W, Kozel D, Hauser J, Souery D, Placentino A, Strohmaier J, Perroud N, Zobel A, Rajewska-Rager A, Dernovsek MZ, Larsen ER, Kalember P, Giovannini C, Barreto M, McGuffin P, Aitchison KJ (2009) Adverse reactions to antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry 195(3):202–210

Val JA, Amorós BG, Martínez VP, Fernández Ferre ML, León SM (1992) Descriptive study of patient compliance in pharmacologic antihypertensive treatment and validation of the Morisky and Green test. Aten Primaria 10(5):767–770

Vieta E, Blasco-Colmenares E, Figueira ML, Langosch JM, Moreno-Manzanaro M, Medina E (2011) WAVE-bd Study Group. Clinical management and burden of bipolar disorder: a multinational longitudinal study (WAVE-bd study). BMC Psychiatry 11:58

Wheeler K, Wagaman A, McCord D (2012) Personality traits as predictors of adherence in adolescents with type I diabetes. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 25(2):66–74

World Health Organization (2003) Investing in mental health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, FEDER Unión Europea (PI10/00955).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De las Cuevas, C., Peñate, W. & Sanz, E.J. Risk factors for non-adherence to antidepressant treatment in patients with mood disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70, 89–98 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1582-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1582-9