Abstract

Purpose

To assess the methodological quality of Orphan Medicinal Product (OMP) dossiers and discuss possible reasons for the small number of products licensed.

Methods

Information about orphan drug designation, approval, refusal or withdrawal was obtained from the website of the European Medicines Agency and from the European Public Assessment Reports.

Results

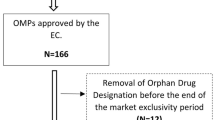

From 2000 up to 2010, 80.9 % of the 845 candidate orphan drug designations received a positive opinion from the European Medicines Agency (EMA)’s Committee on Orphan Medicinal Products. Of the 108 OMP marketing authorizations applied for, 63 were granted. Randomised clinical trials were done for 38 OMPs and placebo was used as comparator for nearly half the licensed drugs. One third of the OMPs were tested in trials involving fewer than 100 patients and more than half in trials with 100–200 cases. The clinical trials lasted less than one year for 42.9 % of the approved OMPs.

Conclusion

Although there may have been some small improvements over time in the methods for developing OMPs, in our opinion, the number of patients studied, the use of placebo as control, the type of outcome measure and the follow-up have often been inadequate. The present system should be changed to find better ways of fostering the development of effective and sustainable treatments for patients with orphan diseases. Public funds supporting independent clinical research on OMPs could bridge the gap between designation and approval. More stringent criteria to assess OMPs’ efficacy and cost/effectiveness would improve the clinical value and the affordability of products allowed onto the market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are about 7,000 rare diseases [1] and they affect 30–40 million people in the European Union (EU). The EU legislation encourages pharmaceutical companies to develop drugs for rare diseases, so-called “orphan drugs” [2]. The Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) is responsible for reviewing applications from persons or companies seeking ‘orphan medicinal product designation’ for products they intend to develop for the diagnosis, prevention or treatment of life-threatening or very serious conditions that affect not more than 5 in 10,000 persons in the EU. The COMP recognizes orphan drug status mainly on the basis of epidemiological data (prevalence of the disease ≤ 5/10,000), and potential benefit [2]. For officially designated Orphan Medicinal Products (OMP) the centralized procedure is compulsory when an EU-wide marketing authorization is sought. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is responsible for the initial assessment of the dossier and for deciding whether the medicines meet the necessary quality, safety and efficacy requirements [3].

Orphan status implies incentives for pharmaceutical companies, including 10 years of market exclusivity, protocol assistance, fee reductions for the European Medicines Agency (EMA) centralized procedures, and specific grants for OMP trials. However, only a small number of OMPs have been developed, and even fewer are the diseases they target, with sometimes scantily documented efficacy and poor cost-effectiveness.

How many orphan drugs have been approved?—And how?

Since 2000, when the OMP legislation [2] came into force, up to 2010, 80.9 % of the 845 candidate orphan drug designations [4] have received a positive opinion on their designation by the EMA’s COMP (Table 1). Of the 108 OMP marketing authorizations applied for, 63 were granted, after a mean of 20.5 months from the designation date to the marketing authorization date (range 2–82 months). In the end, of the 684 designated orphan conditions, 73 indications were licensed [5]. Data from two previous reports [6, 7] show that there were no major changes in 2005–2007 compared to 2000–2004, so the two periods can be taken as a whole. Compared to 2000–2007 [7], in 2008–2010, the rate of positive opinions on orphan designation increased, while negative opinions and withdrawals dropped steeply (Table 1). These figures might reflect a better quality of applications for orphan designation in the last few years.

Looking at the marketing authorizations, the proportions of withdrawals and rejections increased, and there were fewer approvals under exceptional circumstances and conditional approvals (Table 1). These figures possibly reflect greater severity in the assessment of OMPs or less complete applications than in the past, and the general attitude of the EMA: 22.1 % of the applications for all drugs, orphan and non-orphan, are withdrawn or rejected, in comparison to 50 % of OMPs; 3.7 % of the overall authorizations are under exceptional circumstances or conditional, in comparison to 21.1 % for OMPs.

To what extent is OMP toxicity assessed?

Preclinical data in the dossiers were fairly satisfactory (Table 2A). Table 3 (see web extra) reports details on preclinical development of authorized OMPs in 2000–2010. Contrary to the requirements established by the EMA itself [8], toxicity studies were not done in two animal species for 11 of the 63 licensed OMPs, including only one from the period 2008–2010. The duration of toxicity studies was also not in line with the EMA requirements [8] for 34 OMPs, including ten from 2008 to 2010. Lack of genotoxicity, carcinogenicity or reproduction toxicity studies is acceptable, or they are not even required [9], for recombinant anticancer agents, or drugs already on the market for more common indications (e.g. busulfan, hydrocarbamide, and mitotane). This is not the case for 5-aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride, aztreonam lysine, dexrazoxane, pegvisomant, and porfimer (the last was withdrawn in May 2012).

Are the OMP clinical profiles evidence-based?

Table 2B summarises the main features of the clinical trials in the OMP dossiers (for details, see Table 4, web extra). Nearly two-thirds of the dossiers included dose-finding studies and the proportion rose in 2008–2010. Similarly, randomized clinical trials were done for 38 OMPs, with a higher proportion in the later period. Placebo was used as a comparator for nearly half the drugs, with no substantial difference in the two periods.

The inappropriate use of placebo in trials with OMPs authorized in 2000–2007 has been discussed [7]. Briefly, in our opinion, placebo was used inappropriately in the case of anagrelide (in place of hydroxyurea), arsenic trioxide (retinoic acid being an adequate control), bosentan, sidenafil and sitaxentan (epoprostenol), cladribine and imatinib (IFN-alpha), ibuprofen (indomethacin), lenalidomide (bortezomib), miglustat (imiglucerase), pegvisomant (somatostatin), rufinamide (benzodiazepines or newer anti-epileptic drugs such as lamotrigine, topiramate or felbamate alone or as add-on to valproate), zinc acetate (tetrathiomolybdate, penicillamine, or trientine), and ziconotide (morphine).

In trials with the molecules licensed in 2008–2010, the use of placebo was questionable in the case of amifampridine (3,4-diaminopyridine), [10] ambrisentan (epoprosternol, bosentan or sitaxentan), [11] romiplostim and eltrombopag (rituximab, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, danazol or dapsone), [12] rilonacept and canakinumab (anakinra) [13].

We are aware that several of the active comparators suggested are not licensed for the indication in question. However, these drugs are commonly employed in clinical practice and should not be ignored.

Ofatumumab was licensed in 2010 only on the basis of an uncontrolled Phase II trial. This follows ten other drugs authorized in 2000–2007 [7]: aglucosidase alpha, anagrelide, dexazoxane, nitisinone and zinc acetate were authorized on the basis of open-label uncontrolled trials; carglumic acid was approved on the basis of a retrospective study; mitotane, betaine and the pediatric indication of hydroxylcarbamide were only supported by a literature analysis. Velaglucerase alfa was approved in 2010 on the basis of its non-inferiority to imiglucerase in Gaucher’s disease.

The adoption of a non-inferiority approach to test OMP efficacy is surprising. By definition, medicines aimed at unmet needs should be tested for their superiority over available treatment, if any, or placebo.

One third of the OMPs (21) were tested in trials involving fewer than 100 patients, more than half (36) in trials with 100–200, only three in trials with more than 1,000 (Table 2C; for details, see Table 4, see web extra). As previously discussed for neralabine, miglustat, clofarabine, algasidase alpha and beta [7], for several OMPs approved in 2008–2010, the small number of patients in the trials is not justifiable (Table 4, see web extra). This was the case with eltrombopag and romiplostim, icatibant, and sapropterin, which were investigated in about 150 patients out of at least 50,000 potential European cases of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura, hereditary angioedema, and hyperphenylalaninemia, and for velaglucerase tested in 35 of the 15,000 potential European cases of type 1 Gaucher disease.

As stated for the OMPs licensed in 2000–2007 [7], the primary end-points were surrogate for drugs authorized in 2008–2010 too. Biochemical parameters (eltrombopag, romiplostim, sapropterin, velaglucerase), scores (amifampridine, icatibant, rilonacept), improvement in walking (ambrisentan), and tumour responses or progression-free survival (all but two anticancer drugs) were adopted, whose clinical importance is questionable.

The clinical trials supporting the marketing authorization applications lasted less than 1 year for 27 out of 63 approved OMPs (42.9 %), 1–2 years for 16 products (25.4 %), and more than 2 years for only ten drugs (15.9 %); for 11 OMPs, the information was not available. Therefore, several OMPs were studied for only short periods in relation to the natural history of the target disease. This holds true not only for algasidase-alpha and beta, pegvisomant, anagrelide and sodium oxybate, and drugs active in pulmonary arterial hypertension or epilepsy, all authorized in 2000–2007 [7], but also for some OMPs licensed between 2008 and 2010, including rilonacept and canakinumab in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, histamine dihydrochloride for maintainance therapy in acute myeloid leukemia, romiplostim and eltrombopag in chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and velaglucerase alpha in type 1 Gaucher disease (Table 4, see web extra).

Are OMPs only for orphan indications?

The 63 OMPs approved in EU have 73 indications, covering 46 diseases. This is because some have multiple indications, but mainly because many were developed for the same disease, e.g. five for pulmonary hypertension, three for chronic myeloid leukemia, and two for Gaucher’s disease. By law [2], these “duplicates” should not be allowed onto the market unless proved “not similar to” and more effective or safer than OMPs for the same indications.

In other cases, pharmaceutical companies purposely seek a licence for a niche indication, e.g. an expressly identified subgroup of patients. As was pointed out in the EMA European Public Assessment Reports [5], once the product is authorized as an OMP, they then try to broaden its use to a larger setting. This applies, for instance, to some anticancer drugs, which make up a significant proportion of the approved OMPs: 22 anticancer OMPs (13 for hematological cancers) have been authorized overall (34.9 %). These include histamine hydrochloride as maintenance therapy for adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission concomitantly treated with interleukin-2; sorafenib and sunitinib in advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma; trabectidin in advanced soft tissue sarcoma and relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Non-antineoplastic OMPs with questionable selective indications include, for instance, pegvisomant intended for resistant acromegaly and aztreonam lysine for chronic pulmonary infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which was selectively studied in patients with cystic fibrosis. Everolimus took the opposite route: first approved for the prophylaxis of organ rejection, it is now also intended for an orphan indication: advanced renal cell carcinoma progressing on after VEGF-targeted therapy.

Another questionable approach is to use slightly modified versions of old products that are already licensed for common diseases or are used off-label to treat a rare disease. The former is the case, for instance, with the anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen, subsequently proposed as treatment for patent ductus arteriosus, or hydroxycarbamide (the antineoplastic hydroxyurea), and more recently also indicated for pain relief in the sickle cell syndrome [5]. The latter is the case with amifampridine in the treatment of Lambert Eaton myasthenic syndrome [14] and caffeine citrate for primary apnea of premature newborns.

Final remarks

Orphan drug legislation in the United States and Europe is intended to encourage drug companies to develop drugs whose development costs would not otherwise be economic due to the small number of target patients. In the 25 years since the introduction of the US legislation, the FDA has approved 250 drugs for roughly 200 diseases, corresponding to 363 products (15.8 %) of the 2,299 designated [15]. In the decade following adoption of the EU regulation, the EMA approved 63 OMPs for 46 diseases. The higher absolute figures and rate of approvals in US may result from the longer-lasting experience, since the Orphan Drug Act was adopted in 1983. Despite the improved trend in EU approvals, which has paralleled the US authorizations [16, 17], nearly all the currently estimated 7,000 rare diseases, with approximately 250 new diseases described annually, [18] still await treatments. Only a few of these orphans have been tackled, and then not necessarily cured or even effectively treated.

It is a cause for concern that the efficacy and safety profiles of orphan drugs are so lacking. There may have been some small improvements over time in the methods for developing OMPs: toxicology studies in rodents and non-rodents, dose-finding studies and randomized clinical trials have been done for more drugs. However, the number of patients studied, the use of placebo as control, the type of outcome measure and the length of follow-up have often been inadequate. So was the adoption of non-inferiority designs, since the market exclusivity rule [2] implies that no similar competitive product is to be placed on the market unless it proves clinically superior to licensed OMPs. It is conceivable that the information from short-term, small-number trials addressing surrogate endpoints cannot prevent regulatory bodies from approving treatments for orphan conditions. However, this is only acceptable as an interim attitude. The regulatory authorities should take the opportunities of the conditional approval granted to OMPs to foster independent research on the open methodological issues as specific post-marketing obligations.

Many drug companies seem merely to aim their efforts at extending the indications for drugs that are already available rather than developing new treatments. This reflects a marketing strategy that is not necessarily in the best interests of patients or National Health Services (NHS), but is, of course, favorable to the drug companies: the conditions of the marketing authorization and price agreed with regulatory authorities are those acknowledged for OMPs, but revenues are often as high as or even higher than any generic treatment for common diseases. [14, 19]

There is a need to reflect on these findings and consider whether the present system should be changed. A specific European fund might possibly bridge the persistent gap between designations and approvals by supporting the preclinical and clinical steps along the road from discovery to the medicinal product. The EMA should require better evidence of the clinical efficacy of OMPs before they are allowed onto the market, and should consider the possibility of withdrawing the orphan status and the relative incentives when new, broader indications are approved for OMPs. The threshold for orphan status should be lowered to concentrate the efforts on really rare diseases, also considering the expansion of the EU to 27 member states [20]. NHS reimbursement schemes should only allow OMPs with affordable cost-effectiveness and renegotiate the prices when new indications are authorized.

Probably, in the light of the experience gained so far, it is time to review the current rules and find better ways of fostering the development of effective and sustainable treatments for patients with orphan diseases.

References

Orphanet. The portal for rare diseases and orphan drugs. Available at: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/index.php?lng=EN. Accessed 19.07.2012

Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1999 on orphan medicinal products. (2000) Off J Eur Communities. 22.01.2000. L18: 1–5

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:2001L0083:20070126:en:PDF Accessed 19.07.2012

European Medicines Agency. Rare disease (orphan) designations. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/orphan_search.jsp&murl=menus/medicines/medicines.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d12b Accessed 19.07.2012

European Medicines Agency Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed 19.07.2012

Joppi R, Bertele’ V, Garattini S (2006) Orphan drug development is progressing too slowly. Br J Clin Pharmacol 61(3):355–360

Joppi R, Bertele’ V, Garattini S (2009) Orphan drug development is not taking off. Br J Clin Pharmacol 67:494–502

Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Note for guidance on duration of chronic toxicity testing in animals (rodent and non rodent toxicity testing). May (1999). Available at: http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ich/ 030095en.pdf Accessed 19.07.2012

Committee for Medicinal Products for human use. ICH guideline S6 (R1)—preclinical safety evaluation of biotechnology-derived pharmaceuticals. March (1998). Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002828.pdf. Accessed 19.07.2012

Keogh M, Sedehizadeh S, Maddison P. Treatment for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. The Cochrane Collaboration (2011) Issue 2. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003279/frame.html Accessed 19.07.2012

Anonymous. Treatment for pulmonary arterial hypertension. DynaMed. Available at: http://web.ebscohost.com/dynamed/detail?vid=7&hid=123&sid=1edbca12-c7a5-4663-8308-fa9135beb6de%40sessionmgr113&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZHluYW1lZC1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#db=dme&AN=115043 Accessed 19.07.2012

Anonymous. Treatment for immune thrombocytopenia. DynaMed. Available at: http://web.ebscohost.com/dynamed/detail?vid=9&hid=123&sid=1edbca12-c7a5-4663-8308-fa9135beb6de%40sessionmgr113&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZHluYW1lZC1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#db=dme&AN=114263 Accessed 19.07.2012

Kubota T, Koike R (2010) Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: background and therapeutics. Mod Rheumatol 20:213–221

Hawkes N, Cohen D (2010) What makes an orphan drug? BMJ 341:c6459

http://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/DevelopingProductsforRareDiseasesConditions/HowtoapplyforOrphanProductDesignation/ucm216147.htm Accessed 19.07.2012

Bashaw ED, Fang L (2012) Clinical pharmacology and orphan drugs: an informational inventory 2006–2010. Clin Pharmacol Ther 91:932–936

Thorat C, Xu K, Freeman SN et al (2012) What the Orphan Drug Act has done lately for children with rare diseases: a 10-year analysis. Pediatrics 129:516–521

European Commission. Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions on rare diseases: Europe’s challenges. 2008 Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_threats/non_com/docs/rare_com_en.pdf Accessed 19.07.2012

Dear JW, Lilitkarntakul P, Webb DJ (2006) Are rare diseases still orphans or happily adopted? The challenges of developing and using orphan medicinal products. Br J Clin Pharmacol 62:264–271

Garattini S (2012) Time to revisit the orphan drug law. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 68(2):113

Acknowledgment

We thank J.D. Baggott for editing.

Conflict of interests

We have no conflict of interests that may be relevant to this work.

Funding

This study was supported by internal institutional funds from the Mario Negri Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joppi, R., Bertele’, V. & Garattini, S. Orphan drugs, orphan diseases. The first decade of orphan drug legislation in the EU. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69, 1009–1024 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1423-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1423-2