Abstract

Background

The diffusion of innovations model proposes that early adopters of innovation influence others. This study was undertaken to determine if early prescribers and users of newly marketed drugs had different sociodemographic and professional characteristics as compared to majority and late users and prescribers.

Methods

After market availability in Manitoba, Canada, of celecoxib, alendronate, clopiodogrel and pantoprazole, time to first prescriptions was determined. Early, majority and late adopters of the new drug were characterized by this diffusion time. The prescription, health and prescriber records were compared across adopter categories. The likelihood of being an early or late prescriber or user of the new medications according to patient demographic characteristics, physician factors (specialty and place of training) and neighborhood income was determined with polytomous logistic regression.

Results

Celecoxib demonstrated a much more rapid uptake into routine use than the other drugs. More than 300 Manitoba physicians prescribed celecoxib within two weeks of market availability. Early prescribers of celecoxib were more likely than majority prescribers to be general practitioners (OR = 1.81, 95%CI: 1.40–2.35) and have hospital affiliations (OR = 1.35, 95%CI: 1.03–1.77). Early users of celecoxib were more likely than the majority to have arthritic conditions, have a high income and have paid out-of-pocket for their prescription. For alendronate, clopidogrel and pantoprazole, only prescription drug coverage predicted adopter category. Early prescribers of one new drug were not early prescribers of the other new drugs.

Conclusion

No common group of patients or physicians who were early prescribers or users of all four medications was described.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

An understanding of physician and patient behavior associated with prescribing is essential to predict the utilization of newly marketed drugs [1]. The use of newly marketed drugs contributes to escalating expenditures on pharmaceuticals, and little is known about prescriber or patient characteristics associated with early use of new drugs. Although newly marketed drugs play an important role in expanding treatments for many indications, oftentimes, fully published randomized controlled trials are lacking at the time of marketing, and the risk to benefit ratio of new drugs has not been fully evaluated [2]. Factors influencing new prescribing of COX-2 anti-inflammatory drugs, bisphosphonates, antiplatelets, and proton pump inhibitors are not well described [3–12]. The diffusion of innovations model describes the “process by which an innovation is disseminated over time among members of a social system” [13]. This theory proposes early, majority and late adopters of an innovation, and characterizes early adopters as idea champions who influence colleagues through example or direct communication [14–19]. The diffusion of innovations model has applications to drug prescribing, but has been used in population-based studies to a limited extent. Steffensen at al observed that diffusion of prescribing was highly drug dependent [20]. Tamblyn et al. observed an 8–17 fold difference in new drug utilization rates by Quebec physicians [21]. Dybdahl et al. noted that early adoption of one group of drugs did not predict early adoption of other new drugs in Denmark [22].

The goal of this study was to test a model which could predict utilization of newly marketed drugs. The primary objective was to determine whether early or late prescribing was related to user and prescriber characteristics, and whether these characteristics were constant across individual drugs. This study sought to evaluate if early users and prescribers of new drugs had different sociodemographic and professional characteristics from majority or late users and prescribers, and may provide further information about an early adopter or user of newly marked medications [23].

Methods

Design

A comparative analysis of four newly marketed drugs over the time period 1995–2000 was conducted: these included celecoxib, alendronate, clopidogrel and pantoprazole. These drugs were selected for analysis because they were newly marketed brand name drugs used broadly in the population. The diffusion of prescribing of each drug (time between date of market availability and first prescription for each physician in the province) was described over a one-year period, and early, majority and late prescribers were identified [18, 20].

Setting

Data were obtained from the population-based health care databases of the Manitoba Health Services Insurance Plan (MHSIP) in Manitoba, Canada, which included the registration file, physician reimbursement claims, hospital discharge abstracts and prescription records. The MHSIP registration file contains a record (birthdate, sex, geographic location) for every individual eligible to receive insured health services. Physician reimbursement claims for care contain information on diagnosis at the 3-digit level of the ICD-9-CM classification system and physician specialty. Discharge abstracts for hospital services include information on up to 16 ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes. Prescription records from retail pharmacies contain date, drug name and identification number, dosage form, and quantity dispensed as well as patient and prescriber identifiers. Prescription records for all prescriptions dispensed in retail pharmacies in Manitoba are captured, and were the source of information about drug prescribed, prescription drug users and prescribers for this study. The Manitoba Physician Practice database and 1996 Census public-use files were also accessed. The reliability and validity of the MHSIP databases is high for describing population drug use and health care contact [23, 24]. Record linkages through anonymized personal identifiers created longitudinal histories of health care utilization. Ethics approval was obtained through the University of Manitoba. The reliability and validity of the MHSIP databases to describe health services utilization has been well described [24–26].

Population

The study population included all Manitobans receiving at least one prescription for study drug within one year of availability. Both patients who initiated therapy with one of the new drugs without having been on an alternative medication to treat the same medical condition, and patients who switched from an alternative medication to the medication of interest to treat the same medical condition comprised the study population. Manitoba is a Canadian province with approximately 1.2 million and 2000 physicians [26].

Main outcome measures

The study outcome measure was the status of early, majority or late prescriber for each study drug. All first prescriptions written by physicians were identified and the ‘diffusion time’ (date of first prescription minus date of market availability) was calculated. Physicians with prescriptions within the lowest 10% of diffusion times were define as early prescribers, and those in the highest 10% as late prescribers. Majority prescribers had prescriptions which fell inbetween these limits. Although others have used 16% as the cutoff for early adopters [20], we chose 10% due to the rapid uptake of celecoxib as compared to other newly marketed drugs. Patients linked to early, majority or late prescribers were early, majority or late users. If users had prescriptions in multiple adopter categories, the first prescription was selected.

Patient characteristics included: age, gender, neighborhood income quintile (20% of the population residing in the lowest income to 20% of the population residing in the highest income neighborhoods), and prescription reimbursement status (by provincial drug program, Pharmacare or Income Assistance). Physician measures included: age, gender, location of training (Canada/US versus not), specialty [general practitioner (GP), or specialist], years since licensure (<20 years versus more), hospital affiliation (treating physician in the hospital database), and type of practice (solo versus group). A solo practitioner was identified with reimbursement claims from one location without claims from other physicians at this location [27]. For celecoxib prescriptions, presence of a chronic arthritic condition was defined as at least one physician visit for rheumatoid arthritis (ICD9 code = 714) or osteoarthritis (ICD9 code = 715), at least one prescription for a gold preparation, or intermittent or continuous prescriptions for NSAIDs in the year prior to the first celecoxib prescription [26]. Without evidence of a chronic arthritic condition, the prescription was classified as being dispensed for an acute condition.

Analysis

The diffusion of prescribing curve for each drug was compared and the extent of overlap in the categories of early, majority and late prescribers was determined with the kappa statistic. The characteristics of physicians and patients were compared among early and later prescribers, using descriptive statistics. Polytomous logistic regression was used to identify a multivariate model of patient and physician measures which determined the likelihood (odds ratio) of being an early or late prescriber, relative to a majority prescriber (reference category). Polytomous logistic regression was employed in the multivariate analysis, with the majority prescribers as the reference group. The unit of analysis was the physician. Clustering of patients by physician in our analysis was too infrequent to necessitate the use of multi-level analysis. Variables were retained in models at the 95% level of confidence.

Results

In the year following market availability (1999–2000), 1,302 physicians wrote a first prescription for celecoxib in Manitoba. For clopidogrel and alendronate, 594 and 425 physicians, respectively, wrote first prescriptions in the year following availability. Half of physicians wrote their first prescription by the time clopidogrel and alendronate were listed on the Pharmacare formulary (Table 1). Half of pantoprazole prescriptions (n = 447 physicians) were dispensed 87 days after formulary listing. In contrast, 50% of first prescriptions for celecoxib were dispensed 51 days after market availability and 187 days before reimbursement by Pharmacare. Close to 90% of first prescriptions for celecoxib were dispensed before its addition to the provincial formulary.

Celecoxib and alendronate had the most rapid uptake into use (Fig. 1). Ten percent of first prescriptions for alendronate and 25% of prescriptions for celecoxib (>300 physicians) were dispensed within two weeks of availability. Three hundred more physicians wrote a celecoxib prescription in the second month after availability. The number of physicians writing a first prescription for celecoxib declined to a rate of 70 per month four months later, then a rate of 40 per month 10 months after the first introduction of celecoxib. The number of new physicians prescribing alendronate per month also tapered over time, but the rates for pantoprazole and clopidogrel remained steady at 40–50 new physicians per month.

There was little agreement between the percent of prescriptions that fell into the same categories for all drugs (Table 2). Physicians prescribing alendronate or pantoprazole may have not been in practice at the time that celecoxib was released, but this does not explain poor agreement with clopidogrel.

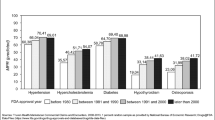

Early users of celecoxib were more often seniors and females (Table 1). Low income persons were less likely to have early access to celecoxib, but use became increasingly more prevalent in the majority and late recipient group (p < 0.0005). Most prescriptions for early users of celecoxib were not reimbursed, but paid out-of-pocket or by private insurance. The reverse was observed for late users of celecoxib. A similar trend was observed for alendronate, clopidogrel and pantoprazole (p < 0.0005 for all), but one quarter of late users of pantoprazole were not reimbursed.

Early prescribers of celecoxib wrote a prescription within 7 days of market availability (Table 1). There was a decreasing trend for age from early to late prescriber (p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Early prescribers of celecoxib were more likely than majority and late prescribers to be general practitioners (GPs), to have a hospital affiliation or to not be trained in Canada/US (p < 0.005) (Table 4). Early prescribers of clopidogrel were more likely to be specialists. Similar to celecoxib, early prescribers of pantoprazole were more likely than the majority and late adopters be hospital affiliated.

In the multivariate model (Table 5), early adopters were more likely than the majority to prescribe celecoxib if individuals had an arthritic condition, were high income or paid out-of-pocket for their prescription. Independent of user characteristics, early prescribers of celecoxib were more likely than the majority to be GPs and to have hospital affiliations. Late prescribers of celecoxib were more likely to be specialists, not to have hospital affiliations and to be in practice for <20 yrs. For alendronate, clopidogrel and pantoprazole, only drug plan status was retained in the multivariate model; late adopters were more likely to prescribe to patients that had Pharmacare coverage for the medication. For clopidogrel, late prescribers were more likely than the majority to be group practitioners.

Discussion

In comparison to alendronate, clopidogrel and pantoprazole, celecoxib enjoyed a dramatically higher uptake. The next highest uptake was by alendronate, followed by clopidogrel and then pantoprazole. Early celecoxib adopters were not the same physicians who were first prescribers of alendronate, clopidogrel and pantoprazole. Early users of all four new drugs were more likely to have paid out-of-pocket for their prescription then to have received reimbursement by the provincial plan. While early prescribers of celecoxib were more likely than later prescribers to be GPs or to have a hospital affiliation, these associations were not found for the other drugs. Our findings are consistent with other studies which have failed to characterize the ‘early prescriber’ across different drugs [21, 22].

Attributes of a drug, such as perceived efficacy and improvement over existing alternatives, have shown to impact early use [28–33]. Attributes of celecoxib that resulted in such a rapid uptake potentially include perception of safety compared to other NSAIDs [12], and its use for an easily recognizable, treatable symptom. Advertising both to physicians and patients may have influenced the uptake of celecoxib. Cost is another important attribute of an innovation. Low income persons were less likely to first receive celecoxib, consistent with the need to pay out-of-pocket for this drug before it achieved drug plan status. The fact that only 12% of first recipients of celecoxib were low income highlights the effect of cost as a barrier to access to prescription drugs [34].

While professional contact between physicians serves as an important communication channel for new drugs [14, 28, 30, 31, 35, 36], information from pharmaceutical representatives is often a first source of drug information [28, 30, 32, 37, 38] and promotional activity influences adoption of new evidence, such as randomized controlled trials [39]. Commercial information is important to GPs and specialists, although more so to GPs [30, 40]. At the time of market availability, there were no published peer reviewed studies evaluating celecoxib [2], and celecoxib was second only to rofecoxib for promotional dollars spent in Canada in 2000 [41]. These events suggest a role of the GP who was identified as an early prescriber in our study in the rapid uptake of celecoxib. Furthermore, promotion of celecoxib was heavily marketed to patients at the time of marketing, and it is known that direct to consumer advertising influences prescriptions for newly marketed drugs [42].

Aspects of the physician’s social system such as location, size and type of physician practice [13, 20, 36, 43] and opinion leader availability [14, 30, 44] also affect new prescribing. Group practice predicts new drug use in some [20, 28, 36], but not other studies [31]. While we observed that late clopidogrel adopters were more likely to work in group practice, this may be a function of increasing use by GPs. Hospital prescribing may influence choice of a new drug [45] via the influence of hospital opinion leaders, increased awareness, or exposure to new drugs through clinical trials [32, 37, 46]. Although only noted to be a significant association in celecoxib use, early prescribers of each study drug were more likely than late prescribers to have hospital affiliations.

Attempts to characterize early prescribers by professional characteristics have yielded mixed results. Our finding that early prescribers of celecoxib were more likely to be GPs is consistent with some, but not all, of the published literature [21, 30, 39, 40, 47, 48]. Early prescribers have also been described as being more professionally oriented [36], different from mainstream medicine [14], and younger than the majority [21, 31, 36], but these factors were not measured or were not significant in our study.

Limitations of this evaluation include the inability of health care data to capture factors that may have influenced prescribing such as patient requests, pharmaceutical industry visits, advertising, physician samples, or perception of the efficacy and safety.

However, we have tested the diffusions of innovation model on population-based data and have identified characteristics of early prescribers, such as hospital affiliation and GP status, which are helpful in the development of targeted educational strategies to promote the appropriate use of newly-marketed drugs. A further limitation includes the use of first prescription to classify early adopters. This definition of early adopters may not have been as sensitive to capturing early adopters, as for example, a measure of the density of prescriptions for new medications after market availability. Additionally, a physician’s first prescription for a newly marketed drug may have been a repeat prescription for a drug initiated by another doctor. This would misclassify the prescription as first use in the patient, but would not misclassify first prescribing of the drug by that physician.

Following availability, celecoxib demonstrated a faster uptake then alendronate, pantoprazole and clopidogrel. No common group of patients or physicians who were early prescribers or users of all four medications emerged.

References

Britten N, Ukoumunne O (6-12-1997) The influence of patients’ hopes of receiving a prescription on doctors’ perceptions and the decision to prescribe: a questionnaire survey. BMJ 315:1506–1510

Therapeutics Initiative (1999) Celecoxib (Celebrex) Is it a breakthrough drug? Therapeutics Letter August/September:1–2

Bull SA, Conell C, Campen DH (2002) Relationship of clinical factors to the use of Cox-2 selective NSAIDs within an arthritis population in a large HMO. J Manag Care Pharm 8:252–258

Cox ER, Motheral B, Frisse M, Behm A, Mager D (2003) Prescribing COX-2s for patients new to cyclo-oxygenase inhibition therapy. Am J Manag Care 9:735–742

Fitt NS, Mitchell SL, Cranney A, Gulenchyn K, Huang M, Tugwell P (20-3-2001) Influence of bone densitometry results on the treatment of osteoporosis. CMAJ 164:777–781

Goldstein LB, Bonito AJ, Matchar DB, Duncan PW, DeFriese GH, Oddone EZ, Paul JE, Akin DR, Samsa GP (1995) US national survey of physician practices for the secondary and tertiary prevention of ischemic stroke. Design, service availability, and common practices. Stroke 26:1607–1615

Hungin AP, Rubin GP, O’Flanagan H (1999) Long-term prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 49:451–453

Jaglal SB, McIsaac WJ, Hawker G, Jaakkimainen L, Cadarette SM, Chan BT (31-10-2000) Patterns of use of the bone mineral density test in Ontario, 1992–1998. CMAJ 163:1139–1143

Quartero AO, Smeets HM, de Wit NJ (2003) Trends and determinants of pharmacotherapy for dyspepsia: analysis of 3-year prescription data in The Netherlands. Scand J Gastroenterol 38:676–677

Solomon CG, Connelly MT, Collins K, Okamura K, Seely EW (2000) Provider characteristics: impact on bone density utilization at a health maintenance organization. Menopause 7:391–394

Solomon DH, Levin E, Helfgott SM (2000) Patterns of medication use before and after bone densitometry: factors associated with appropriate treatment. J Rheumatol 27:1496–1500

Solomon DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Avorn J (15-12-2003) Determinants of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor prescribing: are patient or physician characteristics more important? Am J Med 115:715–720

Rogers EM (1995) Diffusion of innovations

Greer AL (1988) The state of the art versus the state of the science. The diffusion of new medical technologies into practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 4:5–26

Hayward RS, Guyatt GH, Moore KA, McKibbon KA, Carter AO (1997) Canadian physicians’ attitudes about and preferences regarding clinical practice guidelines. Can Med Assoc J 156:1715–1723

Kanouse DE, Jacoby I (1988) When does information change practitioners’ behavior? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 4:27–33

McKinlay JB (1981) From “promising report” to “standard procedure”: seven stages in the career of a medical innovation. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly/Health and Society 59:374–411

Miké V, Krauss AN, Ross GS (1998) Responsibility for clinical innovation: a case study in neonatal medicine. Eval Health Prof 21:3–26

Robert G, Gabbay J, Stevens A (1998) Which are the best information sources for identifying emerging health care technologies? An international Delphi survey. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 14:636–643

Steffensen FH, Sorensen HT, Olesen F (1999) Diffusion of new drugs in Danish general practice. Fam Pract 16:407–413

Tamblyn R, McLeod P, Hanley JA, Girard N, Hurley J (2003) Physician and practice characteristics associated with the early utilization of new prescription drugs. Med Care 41:895–908

Dybdahl T, Andersen M, Sondergaard J, Kragstrup J, Kristiansen IS (2004) Does the early adopter of drugs exist? A population-based study of general practitioners’ prescribing of new drugs. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 60: 667–672

Anderson DM, Needle RH, Mosow SR (1986) Diffusion of innovations in health promotion: a microcomputer-enhanced program for children. Fam Commu Health 9:27–36

Kozyrskyj AL, Mustard CA (1998) Validation of an electronic, population-based prescription database. Ann Pharmacother 32:1152–1157

Robinson JR, Young TK, Roos LL, Gelskey DE (1997) Estimating the burden of disease. Comparing administrative data and self-reports. Med Care 35:932–947

Lix LM, Yogendran M, Burchill C et al (2006) Defining and validating chronic diseases: an administrative data approach. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Winnipeg

Menec VH, Black C, Roos NP, Bogdanovic B, Reid R (1999) Defining practice populations for primary care: methods and issues. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Winnipeg

Buban GM, Link BK, Doucette WR (15-2-2001) Influences on oncologists’ adoption of new agents in adjuvant chemotherapy of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 19:954–959

Groves KEM, Flanagan PS, MacKinnon NJ (2002) Why physicians start or stop prescribing a drug: literature review and formulary implications. Formulary 37:186–194

Jones MI, Greenfield SM, Bradley CP (18-8-2001) Prescribing new drugs: qualitative study of influences on consultants and general practitioners. BMJ 323:378–381

Peay MY, Peay ER (1994) Innovation in high risk drug therapy. Soc Sci Med 39:39–52

Prosser H, Walley T (2003) New drug uptake: qualitative comparison of high and low prescribing GPs’ attitudes and approach. Fam Pract 20:583–591

Wieringa NF, Denig P, de Graeff PA, Vos R (2001) Assessment of new cardiovascular drugs. Relationships between considerations, professional characteristics, and prescribing. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 17:559–570

Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, Abrahamowicz M, Scott S, Mayo N, Hurley J, Grad R, Latimer E, Perreault R, McLeod P, Huang A, Larochelle P, Mallet L (24-1-2001) Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA 285:421–429

Coleman J, Menzel H, Katz E (1966) Medical innovation–a diffusion study. Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis

Weiss R, Charney E, Baumgardner RA, German PS, Mellits ED, Skinner EA, Williamson JW (1990) Changing patient management: what influences the practicing pediatrician? Pediatrics 85:791–795

Prosser H, Almond S, Walley T (2003) Influences on GPs’ decision to prescribe new drugs-the importance of who says what. Fam Pract 20:61–68

Pugh MJ, Anderson J, Pogach LM, Berlowitz DR (2003) Differential adoption of pharmacotherapy recommendations for type 2 diabetes by generalists and specialists. Med Care Res Rev 60:178–200

Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Soumerai SB (15-10-2003) Synergy between publication and promotion: comparing adoption of new evidence in Canada and the United States. Am J Med 115:467–472

Fendrick AM, Hirth RA, Chernew ME (1996) Differences between generalist and specialist physicians regarding Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol 91:1544–1548

CBC News (2002) Targeting doctors. http://www.cbc.ca/disclosure/archives/0103_pharm/docs/totalpromodollars.pdf

Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, Kazanjian A, Bassett K, Lexchin J, Evans RG, Pan R, Marion SA (2002) Influence of direct to consumer pharmaceutical advertising and patients’ requests on prescribing decisions: two site cross sectional survey. Br Med J 324:278–279

Behan K, Cutts C, Tett SE (2005) Uptake of new drugs in rural and urban areas of Queensland, Australia: the example of COX-2 inhibitors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 61:55–58

Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Gurwitz JH, Guadagnoli E, Hauptman PJ, Borbas C, Morris N, McLaughlin B, Gao X, Willison DJ, Asinger R, Gobel F (6-5-1998) Effect of local medical opinion leaders on quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 279:1358–1363

Jones MI, Greenfield SM, Jowett S, Bradley CP, Seal R (2001) Proton pump inhibitors: a study of GPs’ prescribing. Fam Pract 18:333–338

McGettigan P, Golden J, Fryer J, Chan R, Feely J (2001) Prescribers prefer people: the sources of information used by doctors for prescribing suggest that the medium is more important than the message. Br J Clin Pharmacol 51:184–189

Ruof J, Mittendorf T, Pirk O, der Schulenburg JM (2002) Diffusion of innovations: treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in Germany. Health Policy 60:59–66

Helin-Salmivaara A, Huupponen R, Virtanen A, Klaukka T (2005) Adoption of celecoxib and rofecoxib: a nationwide database study. J Clin Pharm Ther 30:145–152

Acknowledgement

Data for this research were accessed from the Population Health Research Data Repository at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. The research was funded through an unrestricted grant from Pfizer (formerly Pharmacia) Inc. Pfizer Inc did not contribute to the research design, data analysis or manuscript writing, and was unaware of the results until they were presented publicly. The manuscript may not reflect Pfizer’s opinion or beliefs. Further, the results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by Manitoba Health was intended or should be inferred.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kozyrskyj, A., Raymond, C. & Racher, A. Characterizing early prescribers of newly marketed drugs in Canada: a population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 63, 597–604 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-007-0277-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-007-0277-5