Abstract

Introduction

Scarce information about comparative diagnostic and therapeutic patterns in paediatric outpatients of different countries is found in the literature.

Objective

To describe the similarities and differences observed in diagnosis and therapeutic patterns of paediatric patients of seven locations in different countries.

Design

Cross-sectional, prospective, international comparative, descriptive study.

Patients and methods

A randomly selected sample of 12,264 paediatric outpatients seen in consultation rooms of urban and rural areas and attended by paediatricians or general practitioners of the participating locations. Data on patient demographic information, diagnosis and pharmacological treatment were collected using pre-designed forms. Diagnoses were coded using the ICD-9 and drugs according to the ATC classification.

Results

Among the ten most common diagnoses, upper respiratory tract infections are in the first position in all locations; asthma prevalence is highest in Tenerife (8.4%). Tonsillitis, otitis, bronchitis and dermatological affections are the most common diagnoses in all locations. Pneumonia is only reported in Sofia (3.8%) and Smolensk (2.3%). The average number of drugs prescribed per child varied from 1.3 in Barcelona to 2.9 in Smolensk. There are no great differences in the profile of pharmacological groups prescribed, but a considerable range of variations in antibiotic therapy is observed: prescription of cephalosporins is low in Smolensk (0.7%) and higher in the other locations, from 16.5% (Bratislava) to 28% (Tenerife). Macrolides prescriptions range from 12.6% (Toulouse) to 24.7% (Smolensk), except in Sofia where they drop to 5.6%. Trimethoprim and its combinations are used in Smolensk (23.3%), Sofia (11.8%) and Bratislava (8.7%). Check-up consultations are not recorded in Smolensk and Bratislava, whereas in Toulouse these visits account for 16.2% of all consultations and in the other locations the percentage varies from 6.1% (Tenerife) to 1.9% (Sofia). Homeopathic treatments are registered only in Toulouse.

Conclusion

Except in asthma prevalence, there are no great differences in diagnostic maps among locations. Significant variations in the number of drugs prescribed per child and antibiotic therapies are observed. Areas for improvement have been identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The study of drug use in paediatric outpatients has always been associated with difficulties resulting from the limited number of drug utilisation studies investigating therapeutic patterns in relation to clinical diagnosis in paediatrics. Comparable diagnostic maps are not easily available in the different countries and several drug utilisation studies in children previously published are based only on the availability of drug-sales data [1] or focused on antibiotic prescriptions in general [2, 3], for a group of infectious conditions [4, 5] or are reviews for a concrete diagnosis specifically [6, 7]. Most of the available studies are based on data collected from only one country, without comparisons with other locations [8, 9, 10, 11]. The use of population-based databases is yielding promising results [12, 13, 14] but sometimes they lack the link between diagnosis and indication, data that are difficult to collect due to technical and ethical issues in global databases.

There are significant differences in primary health care organisation among different countries, based on geographical, epidemiological, economical and political considerations. At this moment, the access to scientific evidence is easy, but the prevalence and geographical distribution of the different clinical entities, diagnostic criteria and guidelines, therapeutic habits, possibilities of clinical up-to-date and influences of the market forces vary from one country to another. The real weight of these aspects in the children’s medical care seems to be evident nowadays [15].

Different diagnostic patterns, a drug’s over prescription, early antibiotic therapy in viral infections or inadequate use of second- and third-choice antibiotics are some of the frequent results observed in single-country publications [16]. However, if the samples are not homogeneous and the methodology of the studies are not comparable, as is the case for most of the published studies, the similarities or differences between countries can only be suspected.

The possibility of obtaining a wider range of knowledge about diagnoses and therapeutic patterns among different countries, which could be compared, prompted the DURG (Drug Utilisation Research Group) to start in 1997, a project called CHILDURG, based on positive experiences published previously [17, 18]. From a descriptive angle, the CHILDURG project pretends to detect possible areas of improvement in the therapeutics of outpatient children’s diseases by analysing different variables associated with prescription.

This project has several strengths and limitations. Among the first, the project is one of the first intending to do an international comparative study on drug prescription in children among countries in Europe that are within the EU and others than might become members in the near future, having very different health care settings and economical development. The project is prospective and naturalistic, collecting information as generated in primary care settings and it has been done in places in which no administrative database for collection of health data is at work, linking the diagnoses and indications given to the children with actual therapeutic behaviour.

However, the project has also several limitations. The size of the sample is not enough to assure a complete representation of the whole of each country or even the locations included; nor was it designed to explore the differences among the participating centres or doctors. Nevertheless, it could represent a range of variations within a location or country on the treatment of outpatient children. Second, there was no attempt to measure the accurateness of the diagnoses given by the doctors: they were taken as they were given by them to the children.

In any case, the comparison of diagnoses and treatment patterns might be useful to have local practitioners see the differences with their peers in other countries. The results of this project might constitute the beginning of a new series of investigations or a guide to start measures to improve drug prescription patterns. In this paper, seven locations in Spain, France, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Russia are compared using the same sample collection and methodology.

Patients and methods

The CHILDURG project is based on data collected from outpatient paediatric consultation rooms in the participating locations.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, prospective, descriptive, international study. A local co-ordinator in each location selected the participating doctors, acting as a contact person with the co-ordinating centre and responsible for the surveillance of the data collection in her/his location. The co-ordinating Centre is located at the Department of Pharmacology of the University of La Laguna (Tenerife, Spain). This centre supervised the standardisation of data collection, created a common database and assured the comparability of sources and data. The national centres performed the data entry locally, and the co-ordinating centre applies a quality checking of data upon reception.

Selection of participating doctors

Paediatricians or general practitioners attending outpatient consultation rooms, preferably not located in hospitals, were considered for selection. Participating physicians were those who, in the first instance, take care of ill children in a general practice setting. They were randomly chosen by each national co-ordinator among the candidates list obtained after personal interviews with practitioners. A booklet guideline with the project description and methodological procedures for the data collection was produced to each of the participants. In Russia the local co-ordinator in Smolensk collected data from five different locations (St-Petersburg, Ekaterinburg, Kazan, Kaliningrad and Smolensk). These five locations are referred in the study with the name of the place were the national co-ordinator was located, Smolensk. In Slovakia, data collected from 28 centres are pooled together, and referred to again by the name of the place where the national co-ordinator was located—Bratislava.

Sample

Patients were selected by random systematic sampling and represented between 10% and 30% of daily consultations of children (below the age of 14 years), during a 4- to 7-month period for each participating doctor. In order to avoid seasonal variations, data were collected from April–June to November–December in all locations, except in Valencia (November–March). Data were registered in a pre-designed form (available from the co-ordinating centre) including demographic data, main diagnoses and pharmacological treatment (drug name, dosage and route of administration). If an adverse drug reaction (ADR) was suspected or detected by the doctors, it was also registered in the ADR form (available from the co-ordinating centre), in order to send it to the ADR National or Regional Centre of pharmacovigilance. A summary of the sample collected is shown in Table 1. Data entry and analysis was performed by a specific application based on “File Maker Pro” Database program. Data coding was performed with ICD-9 simplified (3 digits) for diagnoses and ATC (levels 1–4) for drugs.

Results

The average number of registered diagnoses per child was very similar in all locations, from 1.1 in Smolensk to 1.5 in Bratislava. A comparative view of the ten more frequent diagnoses (comprising 72.6–87.7% of total diagnoses) is shown in Table 2, where upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) was in the first position in all locations, ranging from 46% (Smolensk) to 18.3% (Tenerife). Asthma prevalence was higher in Tenerife (8.4%), whereas it accounted for only 2.8% in Toulouse and 1.6% in Sofia. Tonsillitis was a common diagnosis in the top-positions of all locations, but was higher in Sofia (20.7%) than in the other countries (from 12.7% in Bratislava to 4.7% in Toulouse). Otitis, bronchitis and dermatological affections were also common diagnoses in all locations. Pneumonia was only reported in Sofia (3.8%) and Smolensk (2.3%) in the top-10 positions. Gastroenteritis was present in all locations, except in Bratislava, where gastritis and other digestive affections were mainly diagnosed instead. There were no significant differences among locations in the remaining diagnoses.

The average number of drugs prescribed per child experiments significant variations, ranging from 1.3 in Barcelona to 2.9 in Smolensk. Whereas in Tenerife, Barcelona and Valencia only one or two drugs per patient were prescribed (73.7%, 82.5% and 83.8% of total drugs respectively), in Sofia and Smolensk, the trend moved from two to four drugs per patient (75.8% and 69% of total drugs respectively); Bratislava and Toulouse maintained an intermediate position (one to three drugs were prescribed to 76.9% and 73.2% of the patients, respectively, Table 3).

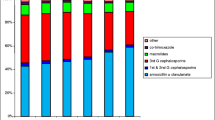

There were not great differences in the pattern of pharmacological groups prescribed in the different locations (Fig. 1). In Toulouse, homeopathic preparations were registered with 1.7% of total drugs prescribed, but were not present in the other locations.

Total number of drugs prescribed to the children in each location, classified according to its ATC group. ATC groups: A alimentary tract and metabolism, B blood and blood forming organs, C cardiovascular system, D dermatologicals, G genito urinary system and sex hormones, H systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulins, J anti-infectives for systemic use, L antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents, M musculo-skeletal system, N nervous system, P antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents, R respiratory system, S sensory organs, V various

Although global use of antibiotics was similar (from 16.2% of all prescriptions in Toulouse to 30% in Barcelona), important differences in the actual antibiotic groups prescribed among locations were observed (Table 4). Global use of penicillins was quite similar in all locations, ranging from 39.7% (Toulouse) to 57.9% (Valencia). The prescription of cephalosporins was low in Bratislava (16.5%) and much reduced in Smolensk (0.72%) but much higher in the other locations, ranging from 19.5% (Barcelona) to 28% (Tenerife). Macrolides were commonly prescribed, from 12.6% (Toulouse) to 24.7% (Smolensk), except in Sofia where they dropped to 5.6%. Trimethoprim and its combinations were used in Smolensk (23.3%), Sofia (11.8%) and Bratislava (8.7%); whereas, in other places, such as Barcelona (2.4%), Tenerife (2.1%) and Toulouse (1.6%), the use was negligible. Aminoglycosides were prescribed only in Smolensk (2.6%) and Sofia (1%). Tetracyclines have a very low prescription (Sofia 3%), not appearing in Barcelona and Tenerife. In Toulouse, the group J01X (including fusidic acid and fosfomycin) comprised 17% of total antibiotics used. In fact this group included a rectal formulation, containing clofoctol (Octofene), which is coded as “other antibacterials”, only used in France, and that is frequently prescribed for children with rhinitis and pharyngitis.

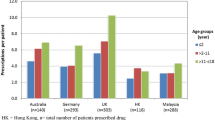

Three frequent diagnoses (common cold when coded as single diagnosis or together with “check-up” visit, tonsillitis and bronchitis) were selected to analyse the antibiotic therapy. The number of children treated with antibiotics is shown in Fig. 2. Patients with common cold received no antibiotics in Bratislava, a little amount of the children were prescribed with them in Tenerife (5.4%) and Valencia (10.8%) and higher rates in Toulouse (31.7%), Smolensk (33.9%), Sofia (37.8%) and Barcelona (39.8%). Antibiotics used were mainly penicillins in Tenerife (83.3%), Barcelona (62.9%) and Sofia (43.5%), cephalosporins in Valencia (50%), Trimethoprim and combinations in Smolensk (53.3%) and the ATC group J01X (mentioned above) in Toulouse (61.5%).

Acute tonsillitis is treated in most cases with antibiotics (ranging from 87.9% of total cases in Sofia and Tenerife to 99.3% in Bratislava), with a slight diminution in Valencia (73%). Antibiotics used are mainly penicillins (>52% in all locations), with a significant prescription of macrolides in Smolensk (44.6%) and cephalosporins in Toulouse (28%), Sofia (19.3%) and Tenerife (19.2%).

Antibiotic therapy on acute bronchitis varies from a moderate prescription in the “western” locations (from 32.3% of children treated with antibiotics in Valencia to 55.9% in Toulouse), to higher rates of antibiotic therapies in Eastern Europe (from 79.5% in Sofia to 87.4% in Bratislava). Similitudes and differences in the groups of antibiotic used are showed in Table 5: in Smolensk, cephalosporins are not used for this diagnosis, with low prescription in Barcelona (12.3% of total antibiotics prescribed for bronchitis) and increasing its use in the other locations (from 19% in Toulouse to 40.6% in Sofia). Macrolides usage in acute bronchitis is maximum in Barcelona (38.6%) and minimum in Sofia (8.1%). Trimethoprim is prescribed mainly in Smolensk (22.4%), and not at all in Tenerife, Valencia and Barcelona.

If we consider the check-up consultations for healthy children, Smolensk’s and Bratislava’s patients were not reported to receive check-up consultations, whereas in Toulouse these visits were frequent (16.2%) and in the other locations the percentage varied from 6.1% (Tenerife) to 1.9% (Sofia). In those check-up visits, children were prescribed occasionally in Barcelona and Sofia (only vitamins and minerals), more frequently in Tenerife, where vitamin D (or A&D) and iron supplements were prescribed to 10.6% of patients in check-up, and very frequently in Toulouse, where 68.1% and 32.1% of the children received vitamin D (or A&D) and fluor supplements, respectively.

Discussion

This study was a prospective naturalistic one. There was no attempt whatsoever to confirm the reliability of the clinical diagnoses stated by the practitioners. This would have been both impossible and not advisable. In fact, the study tried to analyse the prescription patterns for clinical conditions to which different doctors apply the same clinical label. The criteria to establish these diagnoses might be slightly different from one country to another, but it is assumed a substantial similarity on the clinical conditions presented by (otherwise) “healthy” children, and the ability of practitioners to follow general international guidelines. This study relies on the diagnoses and clinical experience of the participating doctors, even if differences at that level might account for a substantial amount of the unexplained differences in the results. Diagnostic patterns are very similar, as well as the global pharmacological groups prescribed, in the different locations, which is in agreement with the similarities on the diagnosis maps. These patterns are also consistent with similar reported findings elsewhere [10, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20].

The trend to prescribe a low number of drugs per child changes from western to eastern locations. A study published in 1988 reported an average number of 2.3 drugs per child in Tenerife [17], dropping to 1.4 drugs per child in the present study, so that a significant improvement in this area was naturally observed in a relatively short period of time.

Antibiotics were over-prescribed also in this sample of general practice [15, 16, 21]. Analysing antibiotic therapies, and considering specific diagnosis, the differences among patterns and locations appeared immediately. Three frequent acute infections have been selected to show the gaps existing between locations: common cold, tonsillitis and bronchitis. It is an undeniable fact that common cold must not be treated with antibiotics in the first instance, but the observed high rates of antibiotics prescribed (including second-line drugs, such as cephalosporins and macrolides) (except in Bratislava) are not in agreement with this scientific evidence.

Although the prevalence of viral (as opposed to bacterial) tonsillitis is expected to be high, these infections are treated with antibiotics in most cases (>87% in all locations, except in Valencia). Penicillin is the first-choice antibiotic for bacterial acute tonsillitis in up-to-date recommendations [22], but high rates of macrolides and cephalosporins are prescribed in the studied locations. Other published studies in particular locations refer to a lower use of antibiotics [23] for the same indication.

The American Academy of Pediatrics [22] discourages the antibiotic treatment of the acute bronchitis, except in specific cases, such as cough with a duration of over 10–14 days or infection caused by Bordetella Pertussis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Recent meta-analysis [6, 24] only found a modest benefit of the antibiotic therapy in a minority of patients, highlighting the fact that the subgroups that could be treated are not clearly identified. In our sample, high rates of antibiotic prescription for bronchitis are observed in all locations studied, especially in the Eastern ones (>79% of children treated); similar rates are reported in other studies [25, 26, 27]. A wide range of first-choice antibiotics including cephalosporins (mainly in Tenerife and Sofia) and macrolides (especially in Barcelona) are observed. There is no single explanation for these prescription patterns for acute bronchitis and there is a controversy in the literature about its treatment: whereas in one study some physical signs seems to play an important role in the clinician decision to prescribe antibiotics for respiratory infections [28], another study [29] showed that symptoms and signs were poor predictors of antibiotic use in acute bronchitis.

Homeopathic medicine is not considered as a scientific or alternative therapy by most “traditional” physicians. Some causes for concern on the use of these alternative medicines are the recommendation for not-immunising children and the possible failure to recognise potentially serious illnesses [30]. However, although physicians demand scientific evidence, in most cases they are ignorant about homeopathy and alternative medicines, and are at risk of not understanding patient’s expectations [31]. In a Norwegian study [32], 50% of doctors tended to be inclined towards homeopathic treatment for some specific conditions, mainly anxiety, migraine and hay-fever. The fact that these therapies were only registered in Toulouse seems to indicate an underestimation or a rejection of this type of treatment by the doctors in the other locations.

In conclusion, diagnosis maps and global pharmacological groups prescribed are very similar in all locations. The number of drugs prescribed per child presents a wide variation between locations, and should be decreased in most of them. Important differences are observed in the antibiotic therapies, with a general over prescription and a significant use of broad-spectrum antibiotics instead of the recommended first-choice for infectious conditions.

How to apply the results of this study to health-care decisions is not a direct consequence of it. The clinical decision treating a child is based on a series of multiple interacting factors: the clinical setting, the expectation of both the parents and the physicians, the diagnosis, the availability of drugs, academic and therapeutic traditions, and the clinical judgement of the physician after discussing with the parents and the child [15, 33]. This paper shows how decisions that should be deemed initially as correct and adequate can be very different from one location to another. The study shows that big differences occurred, despite the general agreement of clinical guidelines and “consensus conferences”.

Reference

Hong SH, Shepherd MD (1996) Outpatient prescription drug use by children enrolled in five drug benefit plans. Clin Ther 18:528–545

McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM (2002) Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents. JAMA 287:3096–3102

Vaccheri A, Castelvetri C, Esaka E, Del Favero A, Montanaro N (2000) Pattern of antibiotic use in primary health care in Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 56:417–425

Nyquist AC, Gonzales R, Steiner JF, Sande MA (1998) Antibiotic prescribing for children with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis. JAMA 279:875–877

Dowell SF, Schwartz B, Phillips WR (1998) Appropriate use of antibiotics for URIs in children. Part I. Otitis media and acute sinusitis. The Pediatric URI Consensus Team. Am Fam Physician 58:1113–1123

Smucny J, Fahey T, Becker L, Glazier R, McIsaac W (2003) Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD000245

Glasziou PP, Hayem M, Del Mar CB (2003) Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD000219

Cazzato T, Pandolfini C, Campi R, Bonati M (2001) Drug prescribing in out-patient children in Southern Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 57:611–616

Wessling A, Soderman P, Boethius G (1991) Monitoring of drug prescriptions for children in the county of Jamtland and Sweden as a whole in 1977–1987. Acta Paediatr Scand 80:944–952

Collet JP, Bossard N, Floret D, Gillet J, Honegger D, Boissel JP (1991) Drug prescription in young children: results of a survey in France. Epicreche Research Group. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 41:489–491

Niclasen BV, Moller SM, Christensen RB (1995) Drug prescription to children living in the Arctic. An investigation from Nuuk, Greenland. Arctic Med Res 54[Suppl 1]:95–100

Thrane N, Sorensen HT (1999) A one-year population-based study of drug prescriptions for Danish children. Acta Paediatr 88:1131–1136

Madsen H, Andersen M, Hallas J (2001) Drug prescribing among Danish children: a population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 57:159–165

McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM (2002) Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents. JAMA 287:3096–3102

Sanz EJ (1998) Drug prescribing for children in general practice. Acta Paediatr 87:489–490

Sanz E (2001) Are antibiotics overprescribed in primary care? Acta Paediatr 90:1223–1225

Sanz EJ, Boada JN (1988) Drug utilization by children in Tenerife Island. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 34:495–499

Sanz EJ, Bergman U, Dahlstrom M (1989) Paediatric drug prescribing. A comparison of Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain) and Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 37:65–68

Schindler C, Krappweis J, Morgenstern I, Kirch W (2003) Prescriptions of systemic antibiotics for children in Germany aged between 0 and 6 years. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 12:113–120

Cazzato T, Pandolfini C, Campi R, Bonati M (2001) Drug prescribing in out-patient children in Southern Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 57:611–616

Pichichero ME (2002) Dynamics of antibiotic prescribing for children. JAMA 287:3133–3135

Pickering L, Georges P, Baker C, Gerber M, MacDonald N, Orenstein W et al (2000) Red book: report of the committee on infectious diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics, Illinois, p 25

Boccazzi A, Noviello S, Tonelli P, Coi P, Esposito S, Carnelli V (2002) The decision-making process in antibacterial treatment of pediatric upper respiratory infections: a national prospective office-based observational study. Int J Infect Dis 6:103–107

Chandran R (2001) Should we prescribe antibiotics for acute bronchitis? Am Fam Physician 64:135–138

Rautakorpi UM, Lumio J, Huovinen P, Klaukka T (1999) Indication-based use of antimicrobials in Finnish primary health care. Description of a method for data collection and results of its application. Scand J Prim Health Care 17:93–99

Kawamoto R, Asai Y, Nago N, Okayama M, Mise J, Igarashi M (1998) A study of clinical features and treatment of acute bronchitis by Japanese primary care physicians. Fam Pract 15:244–251

Straand J, Rokstad KS, Sandvik H (1998) Prescribing systemic antibiotics in general practice. A report from the More and Romsdal prescription study. Scand J Prim Health Care 16:121–127

Dosh SA, Hickner JM, Mainous AG III, Ebell MH (2000) Predictors of antibiotic prescribing for nonspecific upper respiratory infections, acute bronchitis, and acute sinusitis. An UPRNet study. Upper peninsula research network. J Fam Pract 49:407–414

Hueston WJ, Hopper JE, Dacus EN, Mainous AG III (2000) Why are antibiotics prescribed for patients with acute bronchitis? A postintervention analysis. J Am Board Fam Pract 13:398–402

Lee AC, Kemper KJ (2000) Homeopathy and naturopathy: practice characteristics and pediatric care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 154:75–80

Calderon C (1998) Homeopathic and primary care doctors: how they see each other and how they see their patients: results of a qualitative investigation. Aten Primaria 21:367–375

Pedersen EJ, Norheim AJ, Fonnebe V (1996) Attitudes of Norwegian physicians to homeopathy. A questionnaire among 2019 physicians on their cooperation with homeopathy specialists. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 116:2186–2189

Sanz E (2003) Concordance and children’s use of medicines. BMJ 327:858–860

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanz, E., Hernández, M.A., Ratchina, S. et al. Drug utilisation in outpatient children. A comparison among Tenerife, Valencia, and Barcelona (Spain), Toulouse (France), Sofia (Bulgaria), Bratislava (Slovakia) and Smolensk (Russia). Eur J Clin Pharmacol 60, 127–134 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-004-0739-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-004-0739-y