Abstract

Objective

In patients with schizophrenia, risperidone and olanzapine are the two most commonly used atypical anti-psychotics. A recent meta-analysis based on randomized trials suggests that, in the long term, olanzapine can have a lower frequency of treatment discontinuation (or dropout) in comparison with risperidone. To better test this hypothesis, our observational study was aimed at assessing whether or not this advantage of olanzapine versus risperidone could be confirmed in a patient series examined in an observational setting.

Methods

Our study was based on a retrospective multi-centre observational design. We collected the following information from each patient: demographic characteristics; current anti-psychotic treatment (olanzapine or risperidone, under the condition of a stable therapy over months −1 to −4); cumulative dose of the drug; previous anti-psychotic treatment (during months −5, −6, −7 and/or, when available, also before month −7); daily dose and treatment duration. Our primary analysis traced back the patient’s history from the date of enrollment retrospectively up to month −7. The secondary analysis followed-up the patient’s history prior to month −7, thus extending this retrospective recording as long as possible (depending on what information was actually available for individual patients).

Results

The patients were enrolled from 31 institutions. In our primary analysis (months −1 to −7), a total of 144 patients were included; in this subgroup treated with olanzapine or risperidone as initial drug (n=94), we observed 4 of 54 switches from olanzapine to risperidone and 11 of 40 switches from risperidone to olanzapine (P=0.01). A total of 454 patients were enrolled in our secondary analysis (from month −1 up to month −73); the same comparison showed 9 of 236 switches from olanzapine to risperidone and 17 of 150 switches from risperidone to olanzapine (P=0.004).

Conclusion

Our analysis confirms the results of a recent meta-analysis and shows that olanzapine might imply a lower risk of dropout than risperidone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Risperidone and olanzapine are the two most commonly used atypical anti-psychotics in patients with schizophrenia. These two drugs have been shown to be more effective and better tolerated than typical anti-psychotics [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Direct comparisons of the clinical effectiveness between olanzapine and risperidone have generated contrasting results; there is presently no proof that one drug is consistently superior to the other with regard to primary clinical end points (e.g. reduction of positive and negative symptoms, dropout rates, long-term side effects) [6, 7, 8]. Most of the present evidence about the relative effectiveness of these two drugs comes from randomized trials.

In general, observational studies are thought to contribute to improve the therapeutic picture based on phase-III randomized trials [9, 10]. Since this need to construct data from observational studies applies to the comparison between olanzapine and risperidone as well, we designed this multi-centre observational study. Its aim was to compare olanzapine versus risperidone using the end-point of treatment discontinuation.

In pharmacotherapy, dropout can be related to lack of efficacy, development of adverse effects, or non-compliance [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. When studying the outcome of drug treatments, randomized trials typically explore these three different causes of dropout and record the specific dropout cause for individual cases [13]. In epidemiological studies, the research design must be simpler and the following dichotomic interpretation of the clinical outcome is generally adopted [16]: when there is a continued treatment, the patient is considered a therapeutic success, whereas treatment discontinuation for any reason is considered a therapeutic failure. In this way, when comparing two treatments, the dropout data over time construct two actuarial curves of continued treatment (or freedom from dropout) that summarize the respective treatment outcomes. Some classes of drugs are particularly indicated for conducting these dropout analyses; for example, antiepileptic drugs [16, 17], antidepressants [11], and interferon in multiple sclerosis [19]. Although the area of anti-psychotics has not yet been fully explored using this analysis, the newer agents of this class are good candidates for dropout studies because continued treatments or drug discontinuations are an acceptable proxy of therapeutic success and therapeutic failure, respectively [17].

A recent meta-analysis based on randomized trials [20] suggests that, in the long term, olanzapine can have a lower frequency of treatment discontinuation in comparison with risperidone. To better test this hypothesis, our observational study was aimed at assessing whether or not this advantage of olanzapine versus risperidone could be confirmed in a patient series examined under a naturalistic (or observational) setting.

Methods

Design of the study

Our study was based on a retrospective multi-centre observational design. From 15 May 2002 to 20 August 2002, all consecutive subjects referred either as inpatients to a hospital Psychiatric Unit or as outpatients to a Psychiatric Ambulatory Clinic were eligible for our study.

The inclusion criteria were the following:

-

1.

Diagnosis of schizophrenia

-

2.

Age of at least 18 years

-

3.

Treatment with either olanzapine or risperidone at the date of enrollment (month=0)

-

4.

“Stable” therapy (see below) with this anti-psychotic over the previous 4 months (denoted as months −1, −2, −3 and −4 from the enrollment date)

-

5.

Cumulative dose in this period of at least 80% of the respective defined daily doses or DDD (DDD values: olanzapine, 10 mg/day; risperidone, 5 mg/day)

Data collection

The following information was collected from each of the patients included in the study:

-

1.

Demographic characteristics (sex, age)

-

2.

Mode of patient’s referral upon enrollment, i.e., (a) hospital ward, (b) day-hospital, (c) psychiatric outpatient clinic

-

3.

Information on the anti-psychotic treatment over the previous 4 months (olanzapine or risperidone) including cumulative drug dose and date of treatment initiation

-

4.

Information on the anti-psychotic treatment given before month −4 (i.e., during months −5, −6, −7 and/or, when available, also before month −7), including which drug (olanzapine or risperidone or other), daily dose and treatment duration

This information was obtained from a specific form filled in by the pharmacists of out-patients clinics (based on computerized prescription database) and/or by the hospital psychiatrists; each record was anonymous and was identified only by an alphanumeric code.

Primary analysis

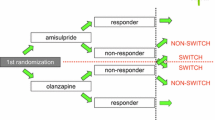

Our retrospective observational study assessed backwards the clinical history of the patients (starting from the date of enrollment with a retrospective follow-up over 7 months). The anti-psychotic being given on enrollment (final drug) was a stable treatment because, according to the inclusion criterion, it had been kept unchanged over the previous 4 months (months −4, −3, −2 and −1). With regard to the treatment given over months −5, −6 and −7, we tested whether or not this treatment was with the same drug given over months −4 to −1. Cases based on a single treatment from month −7 to month −1 were classified as “continued treatment”, whereas cases with a different drug over months −7 to −5 compared with the drug received upon enrollment were classified as “dropout” (with regard to the drug given over months −7 to −5).

In cases of dropout, the transition (i.e., the switch from one drug to another) was one of the following:

-

1.

Initial drug = risperidone; final drug = olanzapine

-

2.

Initial drug = olanzapine; final drug = risperidone

-

3.

Initial drug = any typical anti-psychotic; final drug = olanzapine

-

4.

Initial drug = any typical anti-psychotic; final drug = risperidone

-

5.

Initial drug = any atypical anti-psychotic other than olanzapine or risperidone; final drug = olanzapine

-

6.

Initial drug = any atypical anti-psychotic other than olanzapine or risperidone; final drug = risperidone

A descriptive analysis was planned to examine all of these transitions. A separate specific analysis (with statistical testing) was focused on switches from risperidone to olanzapine and on those from olanzapine to risperidone.

When patients were found to have received three or more different treatments over time in their therapeutic history, the analysis considered only the two most recent treatments and not the previous one(s).

Secondary analysis

In case where our patients’ database included retrospective information on the anti-psychotic treatment for a period longer than 7 months (maximum length of retrospective history = up to month −73), the additional data were examined through this secondary analysis. Compared with the primary analysis (where our dropout recordings were restricted from month −7 to month −5), the secondary analysis considered all dropouts that occurred from month −73 to month −5. Hence, the secondary analysis followed-up the patient’s history prior to month −7 and extended this retrospective recording as long as possible (depending on what information was actually available for individual patients). As in the primary analysis, we tested whether or not the anti-psychotic treatment was based on a single drug given from the beginning of the therapeutic follow-up until month −1. Cases based on a single treatment until month −1 were classified as “continued treatment”, whereas cases with two different drugs given in their therapeutic history (i.e., “initial drug” and “final drug”, respectively) were classified as “dropouts” (with the regard to the “initial drug”). Also in this analysis, dropouts were examined by recording which of the six possible transitions had occurred. An overall analysis was planned to describe all of these transitions. A separate specific analysis (with statistical testing) was focused on switches from risperidone to olanzapine and on those from olanzapine to risperidone. As in our primary analysis, when patients had been given three or more different treatments over time in their therapeutic history, the analysis considered only the two most recent treatments and not the previous one(s).

Statistical testing

Standard statistical methods were used including Fisher’s exact test for the assessment of 2×2 contingency tables.

Results

The study enrolled a total of 454 patients from 31 institutions (hospitals or outpatient clinics, see Appendix A). Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the patients.

Table 2 reports the results of our primary analysis that traced back the patient’s history from the date of enrollment retrospectively up to month −7. In this primary analysis, a total of 144 patients was included. As regards the initial drug, most patients were treated with olanzapine (n=54), risperidone (n=40) or haloperidol (n=24) over months −7 to −5. We observed 15 switches involving olanzapine or risperidone: 4 patients switched from olanzapine to risperidone (4 of 54, 7.4%) and 11 patients (11 of 40, 27.5%) switched from risperidone to olanzapine (P=0.01). The other changes of therapy are described in Table 2.

Table 3 reports the results of our secondary analysis that considered a retrospective period longer than 7 months (maximum length of retrospective history = up to −73 months; median =11.9 months). This analysis enrolled a total of 454 patients. Also in this case, olanzapine (n=236), risperidone (n=150) and the “typical” haloperidol (n=38) were the most frequent initial drugs. Table 3 shows the dropout rate for patients treated only with olanzapine or risperidone as initial drug in this extended period. Twenty-six patients changed therapy: 9 patients (9 of 236, 3.8%) switched from olanzapine to risperidone and 17 patients (17 of 150, 11.3%) switched from risperidone to olanzapine. Also in this secondary analysis the difference was significant in favor of olanzapine (P=0.004).

Discussion and conclusions

Our observational study evaluated olanzapine versus risperidone using the end-point of treatment discontinuation as an index of ineffectiveness. We selected these two drugs and we did not consider clozapine for a number of reasons: (a) there was no recent study comparing clozapine versus olanzapine or risperidone; (b) only one study had a duration of more than 12 weeks [21]; (c) its market in Italy is many-fold less than that of risperidone and olanzapine, and so we did not expect to enroll any substantial number of patients treated with this drug.

Regarding the most recent atypical agent quietapine, the literature does not provide enough material for such analysis; quietapine has in fact much less published information than olanzapine and risperidone.

The results of our two analyses show that, in the management of a psychotic patient, the interruption of treatment and the consequent switch to another drug is quite frequent (Table 2 and Table 3). We found a large number of switches from a typical agent (particularly haloperidol) to risperidone or olanzapine both in the primary (37 of 144, 25.7%) and in the secondary (54 of 454, 11.9%) analysis.

With regard to the two drugs targeted by our study, olanzapine was significantly superior to risperidone when the outcome was expressed as dropout rate both in the primary analysis (with a follow-up of 7 months: 4 switches from olanzapine to risperidone versus 11 switches from risperidone to olanzapine, P=0.01) and in the secondary analysis (with a follow-up longer than 7 months: 9 switches from olanzapine versus risperidone and 17 switches from risperidone to olanzapine; P=0.004).

Regarding the design of our study, it is well known that the value of observational studies is a matter of debate [22, 23, 24] and, of course, our study does not make an exception. Anyway, the scientific community continues to accept them, especially in cases where a strong evidence is lacking concerning the therapeutic question under examination.

A limitation of our study is that the interruption of treatment was not differentiated between cases of clinical ineffectiveness, non-compliance or adverse reactions; however, in the controlled studies published so far, there seems to be no information suggesting that one of these possible causes of treatment interruption is more frequent than another.

Another bias of our study is that when a new anti-psychotic agent is introduced into the market (in our case olanzapine), some patients (in particular, partial responders) might be switched to the new drug under marketing pressure and without any specific clinical need. Actually, our study relies on an (unproven) assumption of ethical prescribing by psychiatrists: without any clinical reason, switching to a new drug because of marketing pressure would in fact be highly unethical.

In conclusion, our observational study confirms the results of a recent meta-analysis based on randomized trials [20] and shows that olanzapine might imply a lower risk of dropout over time than risperidone.

References

Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tran PV, Street JS, Krueger JA, Tamura RN, Graffeo KA, Thieme ME (1997) Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. Am J Psychiatry 154:457–465

Tran PV, Dellva MA, Tollfeson GD, Wentley AL, Beasley CM (1998) Oral olanzapine versus oral haloperidol in the maitenance treatment of schizophrenia and related psychoses. Br J Psychiatry 172:499–505

Tran PV, Dellva MA, Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Potvin JH, Kiesler G (1997) Extrapyramidal symptoms and tolerability of olanzapine versus haloperidol in the acute treatment of schizophrenia J Clin Psychiatry 58:205–211

Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, et al (2002) Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 159:255–260

Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R (2002) The Risperidone-USA-79 Study Group. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 346:16–22

Tran PV, Hamilton SH, Kuntz AJ, Potvin JH, Andersen SW, Beasley C Jr, et al (1997) Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 17:407–418

Purdon SE, Jones BD, Stip E, Labelle A, Addington D, David SR, et al (2000) Neuropsychological change in early phase schizophrenia during 12 months of treatment with olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. The Canadian Collaborative Group for research in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:249–258

Conley RR, Mahmoud R (2001) A randomized double-blind study of risperidone and olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 158:765–774

Benson K, Hartz AJ (2000) A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med 342:1878–1886

Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI (2000) Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies and hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med 342:1887–1892

Anderson IM, Tomenson BM (1995) Treatment discontinuation with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants: an analysis. BMJ 310:1433–1438

Emery P, Zeidler H, Kvien TK, Guslandi M, Naudin R, Stead H, et al (1999) Celecoxib versus diclofenac in long-term management of rheumatoid arthritis: randomised double-blind comparison. Lancet 354:2106–2111

Hamilton SH, Edgell ET, Revicki DA, Breier A (2000) Functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a comparison of olanzapine and haloperidol in a European sample. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 15:245–255

Pope JE, Bellamy N, Seibold JR, Baron M, Ellman M, Carette S, et al (2001) A randomized, controlled trial of methotrexate versus placebo in early diffuse scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum 44:1351–1358

Sees KL, Delucchi KL, Masson C, Rosen A, Clark HW, Robillard H, et al (2000) Methadone maintenance vs. 180-day psychosocially enriched detoxification for treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:1303–1310

Walker MC, Li LM, Sander JW (1996) Long-term use of lamotrigine and vigabatrin in severe refractory epilepsy: audit of outcome. BMJ 313:1184–1185

Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, et al (1997) A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Clozapine in Refractory Schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 337: 809–815

Marson AG, Kadir ZA, Chadwick DW (1996) New antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review of their efficacy and tolerability. BMJ 313:1169–1174

IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group (1995) Interferon beta-1b in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: final outcome of the randomized controlled trial. Neurology 45:1277–1285

Santarlasci B, Messori A (2003) Clinical trail response and dropout rates with olanzapine and risperidone. Ann Pharmacother 4:556–563

Tuunainen A, Wahlbeck K, Gilbody SM (2000) Newer atypical antipsychotic medication versus clozapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2

Pocock SJ, Elbourne DR (2000) Randomized trials of observational tribulations. N Engl J Med 342:1907–1909

Benson K, Hartz AJ (2000) A comparison of observational studies and randomised, controlled trials. N Engl J Med 342:1878–1886

Concato J, Sha N, Horwitz RI (2000) Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med 342:1887–1892

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX A

The coordinators of the study: A Messori, F Pelagotti, B Santarlasci, M Vaiani, S Trippoli, F Vacca, Laboratorio SIFO di Farmacoeconomia, (c/o Azienda Ospedaliera Careggi, Firenze) and the following participants (all located in Italy): Alessandro Bernardini, Niccolini Patrizia, Enrica Bonadeo (Alessandria); Silvia Martinetti, Valeria Recanelga, Guglielmo Occhionero, Giuseppe Bonavolntà, Claudio Cardona (Asti); Italo Santin, Francesco Coppa (Belluno); Daniela Corsini, Boncompagni (Bologna); Marilisa Sebastiani, Angelo Malinconico, Nicola D’Erminio (Campobasso); Teresa Galdieri, Emilio Isu, Enrico Perra, (Cagliari); Vincenzo Inzirillo, Carmelo Florio (Catania); Valeria Scilla, Raffaele Di Lorenzo (Catanzaro); Vittorio Battaglia, Maria Avantaneo, Cecilia Dal cielo, Impallomeni (Cuneo); Piro Brunella, Liguori Giorgio, Giampiero Dramisio, Gina Volpintesta, Nella Felice, Carmela Altomare, Carmela Oriolo, Buccomico Domenico, Francesco Trotta, Giuseppina De Stefano, Nicotera Mario (Cosenza); Giuseppe Taurino, Cristina Martinelli, Stefania Bigini, Fabrizio Lazzerini (Massa Carrara); Erminia Taormina, Parisi (Enna); Roberta Barbaro, G. Raponi, Gastoni (Foligno-Pg); Chiara Cherubini, Ilo Rossi (Ravenna); Barbara Fazzi, Enrico Marchi (Lucca); Rocco Iacovino, Angela Montesano (Matera); Mariangela Dairaghi, Elio Zino (Novara); Giovanni Bologna, Paolo Cironi (Piacenza); Marina Pitton, Calogero Anzallo (Pordenone); Domenica Costantino, Antonio Numera (Reggio Calabria); Giusy Calì, Antonuccio Orazio, Giuseppina Muccio, Gaetano Bozzanca, Luisa Ballerini, Lucia Insiriello, Giuseppe Augello, Antonio Cappellani, Salvina Schiavone (Siracusa); Franco Molter, Renzo De stefani, C. Agostini (Trento); Giuliana Dossi, Puccio Giuseppe (Verbania); Mariella Conti (Viterbo).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pelagotti, F., Santarlasci, B., Vacca, F. et al. Dropout rates with olanzapine or risperidone: a multi-centre observational study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 59, 905–909 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-003-0705-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-003-0705-0