Abstract

Recent studies have indicated that populations of gelatinous zooplankton may be increasing and expanding in geographic coverage, and these increases may in turn affect coastal fish populations. We conducted trawl surveys in the northern California Current and documented a substantial biomass of scyphomedusae consisting primarily of two species (Chrysaora fuscescens and Aurelia labiata). Spatial overlap of these jellyfish with most pelagic fishes, including salmon, was generally low, but there were regions of relatively high overlap where trophic interactions may have been occurring. We compared feeding ecology of jellyfish and pelagic fishes based on diet composition and found that trophic overlap was high with planktivorous species that consume copepods and euphausiid eggs such as Pacific sardines (Sardinops sagax), northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax), Pacific saury (Cololabis saira), and Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi). Moreover, isotope and diet analyses suggest that jellyfish occupy a trophic level similar to that of small pelagic fishes such as herring, sardines and northern anchovy. Thus jellyfish have the potential, given their substantial biomass, of competing with these species, especially in years with low ecosystem productivity where prey resources will be limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In various ecosystems of the world, evidence is accumulating that gelatinous zooplankton populations are trending upward (Mills 2001; Purcell et al. 2001a; Attrill et al. 2007), in sharp contrast to many commercially important fish stocks (Mullon et al. 2005). The mechanisms behind these increases in gelatinous populations are open to speculation but may include climate change (Brodeur et al. 1999; Atkinson et al. 2004; Lynam et al. 2004, 2005; Purcell and Decker 2005; Purcell 2005; Link and Ford 2006; Attrill et al. 2007), species introductions (Shiganova 1998; Mills 2001; Graham and Bayha 2007), eutrophication (Purcell et al. 1999; Arai 2001; Xian et al. 2005), removal of commercially important fish stocks (Parsons and Lalli 2002; Lynam et al. 2006), or some interaction of these factors (Purcell et al. 2007).

In a recent example from the northern Benguela Current off Namibia, Lynam et al. (2006) have suggested that the biomass of pelagic fish stocks was quite high relative to jellyfish biomass in the 1970s and 1980s but has since fallen to approximately one quarter of the jellyfish biomass in recent years. Regardless of whether this change was due to climatic events or overfishing, the outcome has serious implications for the ecosystem and fishing communities.

Because gelatinous zooplankton exhibit rapid growth rates and have the potential to dominate the pelagic biomass of marine ecosystems, several studies have examined potential interactions between fish and jellyfish [see reviews by Arai (1988) and Purcell and Arai (2001)]. Some interactions may benefit pelagic fishes (i.e., provisioning of food or shelter) and in some cases may actually increase survival of young fish (Lynam and Brierley 2007), but the impacts are more likely to be negative (predation on early life stages of fish or competition for limited planktonic food resources). Among the negative impacts, much of the attention has focused on predation effects, since many jellyfish are obligate planktivores and most fish species have planktonic early life stages (Möller 1984; Purcell 1985, 1989; Fancett and Jenkins 1988; Purcell et al. 1994; Shiganova and Bulgakova 2000; Brodeur et al. 2002). Alternatively, jellyfish may have similar trophic requirements as many pelagic fishes, and any reduction in these vertebrate competitors, whether due to climatic changes or overfishing, may allow jellyfish to take over the vacated trophic niche (Shiganova 1998; Lynam et al. 2006). Although the diets of many gelatinous predators have been examined, there are few examples (Purcell 1990; Purcell and Sturdevant 2001) where these diets were directly compared to co-occurring zooplanktivorous pelagic fishes.

Scientists working on marine fisheries and ecosystem issues are becoming increasingly aware of the potential effects of these gelatinous predators on the available prey resources of many coastal ecosystems. Sampling in the northern California Current off Oregon and Washington has indicated that biomass of gelatinous zooplankton (mainly scyphomedusae) can be extremely high (up to 28–64 gC m−3) in nearshore surface waters, especially in late summer (Shenker 1984; Suchman and Brodeur 2005; Suchman unpublished). A substantial spatial overlap between gelatinous macrozooplankton and pelagic fishes has been observed (Reese 2005), and recent independent diet analyses of both jellyfish and finfish (Miller and Brodeur 2007; Suchman et al. 2008) suggest some common shared food resources.

The purpose of our study was to examine in detail the spatial and trophic overlap between two dominant jellyfish and pelagic finfish collected during one cruise (August 2002) off Southern Oregon when substantial catch and diet information was available. Our goal was to determine whether there is a potential for resource competition between these two major trophic groups which comprise the majority of the zooplanktivore biomass of the northern California Current (Ruzicka et al. 2007).

Materials and methods

Field sampling

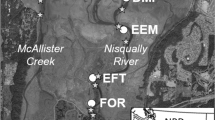

Catch data and pelagic nekton specimens for dietary analyses were taken during a GLOBEC Northeast Pacific Program cruise from 1 to 18 August, 2002. Sampling ranged from Newport, OR (44.6°N) to Crescent City, CA (41.7°N,) and took place at 101 stations located 3–30 nautical miles (5.6–55.6 km) from shore (Fig. 1). Most collections were made during daylight, although some stations were sampled over a diel cycle. Medusae and pelagic fishes were collected using a Nordic 264 rope trawl (30 m wide, 18 m deep) towed in surface waters for 30 min at 6 km h−1. Mesh size of the trawl ranged from 162.6 cm in the throat to 8.9 cm in the cod end, with a 6.1-m long, 0.8-cm mesh liner sewn into the cod end. All medusae and fish were identified to species, counted, and measured (bell diameters of jellyfish, total or fork lengths of fish measured to ±1.0 mm) immediately after capture at sea. Each species was weighed in aggregate (wet weight) using a platform scale. Details and potential biases of the abundance and biomass estimation were discussed by Suchman and Brodeur (2005) and Reese and Brodeur (2006).

Spatial analysis

To identify the spatial overlap associated with the dominant fish species relative to the distribution of the two dominant Scyphomedusae species (Aurelia labiata and Chrysaora fuscescens), we used geostatistical modeling techniques. This method of determining spatial distributions of species and various community characteristics has been used previously and is described in detail in Reese and Brodeur (2006). For each species, we collected and calculated the abundance and biomass at specified sample locations. The values obtained at sample stations were then used to interpolate predicted values at all other locations. Continuous coverage maps were then used to calculate the percent overlap of each dominant nekton species with the jellyfish species.

There are various interpolation methods capable of deriving continuous coverages based on predicted values. We employed a geostatistical method based on statistical models that included autocorrelation. A benefit of utilizing this technique was that in addition to producing continuous prediction surfaces, it provided a measure of the error associated with the predicted values. The initial step in the spatial analysis was to calculate the empirical semivariogram. Each spatial process consisted of observations measured at a location x, which is the sample station defined by latitude and longitude. Two types of directional components, global trends and anisotropy, were examined for their effect on surface predictions, and when present, were incorporated into the analyses (Johnston et al. 2001).

Large outliers can greatly influence interpolated predicted values. These outliers result in an increased nugget effect, which consequently results in higher predicted values with greater uncertainty (Chiles and Delfiner 1999). Chiles and Delfiner (1999) suggested that the extreme outlier values could be reduced to the value of the upper limit of the range, not including the outlier. This method maintains the overall spatial structure in the data and was used when necessary. Empirical semivariograms {γ(h)} were estimated by pooling pairs of observations following the equation given by Matheron (1971):

where Z(x i ) is the value of the variable at location x i , Z(x i + h) is the value separated from x i by distance h (measured in meters), and N(h) is the number of pairs of observations separated by distance h. Exponential and spherical models were fit to the empirical semivariograms to estimate the semivariogram values for each distance within the range of observations (Cressie 1993). Kriging was then used to determine the expected values of the nekton and jellyfish biomass. Kriging forms weights based on local measured values to predict values at unsampled locations such that the nearest measured values have the most influence (Johnston et al. 2001). Weights are derived from the modeled semivariogram which characterizes the spatial structure of the data. The predictor is then formed as the weighted sum of the data such that:

where Z(X i ) is the measured value at the ith location; λ i is an unknown weight for the measured value at the ith location that minimizes prediction error (Cressie 1993), and X 0 is the prediction location. The weighting factor, λ i , depends on the semivariogram, the distance to the prediction location, and the spatial relationships among the sampled values around the prediction location. Cross-validation was used to evaluate the geostatistical results. For each variable, multiple exponential and spherical models were evaluated and compared, and the best model was selected. We used ArcGIS v9.1 with the geostatistical analyst extension in the spatial analyses (ESRI, Redlands, CA).

In some instances there was a lack of autocorrelation in the data, therefore a deterministic interpolation method resulted in better predictions. In these cases, inverse distance weighting (IDW) was used to produce the coverage maps. This method is referred to as a deterministic interpolation method because values are assigned to locations based on the surrounding measured values, the distance between the measured points and the prediction location, and the specified mathematical formulas that determine the smoothness of the resulting surface (Johnston et al. 2001). The IDW method does not require a statistical model that includes autocorrelation as the geostatistical method does, but rather relies simply on the assumption that things that are close to one another are more similar than those that are farther apart. Predicted values for unsampled locations therefore rely on the measured values surrounding the prediction location (Johnston et al. 2001). Measured values closest to the prediction location thus have more influence on the predicted value than those that are farther away. Therefore, the IDW method assumes that each measured point has a local influence that diminishes with distance.

Given the distance between sample stations, coverage maps are not intended to represent small-scale processes but rather to elucidate broad-scale patterns in the spatial distributions of dominant nekton and jellyfish species. Although the data are not synoptic, geostatistically produced maps of sea surface temperature and chlorophyll were found to closely resemble both satellite-derived and in situ sampling maps of temperature and chlorophyll, thus supporting the assumption that the geostatistically produced maps are representative of ocean conditions (Reese et al. 2005).

To examine the amount of spatial overlap of the jellyfish species with the modeled distribution of a particular nekton species, we calculated the percent spatial overlap by dividing the number of overlapping 5 km2 grid cells (with mean or greater biomass values shared by a dominant nekton species and a specific jellyfish species) by the total number of grid cells in the given nekton species area (e.g., where nekton biomass was equal to the mean or greater value) as in the examples shown in Fig. 2. Complete coverage maps for the dominant nekton and jellyfish species were combined and analyzed with ArcGIS v9.1 Spatial Analyst (ESRI, Redlands, CA). For three nekton species, nonzero biomasses were observed at fewer than 15% of the total number of stations sampled. For these species we did not utilize an interpolation method but instead simply calculated the overlap as the number of sample stations where nekton biomass was present within the jellyfish areas (with mean or greater biomass values) divided by the total number of stations where the nekton species biomass was present.

In addition to calculating the percent spatial overlap using an interpolation method, we also calculated spatial overlap using only data collected from the sample stations. These values were calculated with the following equation: (number of stations with both a jellyfish species and a nekton species/number of stations with that nekton species) × 100%. This specifically provides the percentage of stations occupied by a given nekton species that is also occupied by a particular jellyfish species. This is comparable to the method used to calculate spatial overlap using geostatistics, however, the overlaps do not rely on interpolated values.

Diet analysis

Stomach analysis was conducted on a representative subsample of scyphomedusae and pelagic fishes. For their diet composition, scyphomedusae were sampled by dipnetting individuals from the side of the research vessel, thus avoiding regurgitation and cod-end feeding biases from trawl-caught specimens. Medusae were preserved in a 5% buffered formalin solution in separate containers, with individuals dissected in the laboratory within 6 months. Prey items were identified and counted in the surrounding preservative medium, gastric cavities, and oral arms (Suchman et al. 2008). Following collection in surface trawls, pelagic fishes were immediately frozen on ship (−20°C) and later taken to the laboratory for processing. Diet analysis of up to 30 fish per species per station was performed by opening the stomach, assessing fullness and digestive condition, and identifying and quantifying (number and weight) prey taxa (Miller 2006a). For species such as Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax), in which the stomach contents consisted of large amounts of phytoplankton mixed with small zooplankton and euphausiid eggs, the stomach contents were subsampled using a Stempel pipette (Emmett et al. 2005).

Numerical diet composition was summarized by the lowest identifiable taxa and the results of these detailed analyses were reported by Miller (2006a), Miller and Brodeur (2007), and Suchman et al. (2008). Dietary overlaps between each jellyfish species and every pelagic fish species/life history stage were calculated at these detailed taxonomic levels using the percent similarity index (PSI):

where p is the numerical proportion of the kth prey species consumed by predator species i and j. Values > 60% indicate high overlap (Wallace and Ramsay 1983).

Fresh tissue was extracted at sea from jellyfish and forage fishes for stable isotope analysis. For fish, a portion of the left anterior dorsal muscle tissue was extracted, and for jellyfish, part of the umbrella tissue was removed. Both carbon and nitrogen samples were dried in an oven for 24 h at 60°C, and then all samples were pulverized using a mortar and pestle, weighed, and processed on a stable isotope mass spectrometer. Stable isotope ratios are reported in standard δ notation in parts per thousand (‰) relative to PDB (carbon) and air (nitrogen) following a correction for lipid content (Miller 2006a).

Results

Spatial overlap

Distributions of the two jellyfish species differed during August 2002. C. fuscescens was more abundant in the northern part of the study region, whereas A. labiata was more abundant in the south (Suchman and Brodeur 2005). Comparing both the geostatistically produced spatial overlap values with the values obtained using only station data yielded similar overlaps for most fish species (Table 1). Differences between methods were apparent for some species, however, with the geostatistical method showing higher overlap values with C. fuscescens (7 of 9) whereas the opposite was true for A. labiata (all but surf smelt were lower). Since we are using the interpolations to predict if the biomass is simply equal to or greater than the overall mean biomass over the entire sampled area based on station-only data, this is a more conservative estimate for two reasons: (1) we eliminate very large outliers which will greatly increase the local predicted values near those few stations, and (2) we are using “mean or greater” biomass which will eliminate areas where biomass is still rather high, but not quite at the mean biomass. The following results are therefore based on the geostatistically determined spatial overlaps.

Several nekton species showed considerable spatial overlap with C. fuscescens (Table 1). Juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), juvenile coho salmon (O. kisutch), jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus), whitebait smelt (Allosmerus elongatus), and Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi) all had spatial overlap greater than 33%. Thus, considerable portions of the preferred habitat of these nekton species were also occupied by high abundances of C. fuscescens. Moderate spatial overlap was found with surf smelt (Hypomesus pretiosus), northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax), and Pacific sardine, with overlap values ranging from 21.6 to 27.3% (Table 1). Only Pacific saury (Cololabis saira) did not appear to overlap spatially with C. fuscescens. Fewer nekton species showed considerable spatial overlap with A. labiata (Table 1). Surf smelt and Pacific herring showed the greatest spatial overlap (75.0 and 38.0%, respectively), whereas whitebait smelt and Pacific sardine showed no spatial overlap with A. labiata. All other spatial overlaps were negligible.

Diet overlap

During August 2002, diets of C. fuscescens were composed primarily of euphausiid eggs, followed by copepods, euphausiid nauplii/calyptopes and other prey (Fig. 3). A. labiata diets were similar but contained more euphausiid nauplii/calyptopes, pteropods, and larvaceans and fewer copepods than C. fuscescens (Fig. 3). The diet overlap between these two jellyfish was 75.4%.

The diets of pelagic nekton fell into two broad categories. In the first, four species, Pacific sardine, northern anchovy, Pacific herring and Pacific saury had over half their diets comprised of euphausiid eggs by percent number, a proportion similar to that seen for the two jellyfish species (Fig. 3). Whitebait smelt consumed some euphausiid eggs but mostly copepods and to a lesser degree euphausiids. Surf smelt ate a variety of foods but showed relatively little similarity to the diets of either jellyfish. The second category included the remaining predators: juvenile coho salmon, juvenile Chinook salmon, and jack mackerel. These fed predominantly on older stages of euphausiids or fish prey (Fig. 3).

The PSI between each gelatinous species and the pelagic predators reflected similarities and differences observed in the two broad diet groupings described above. Herring, saury, anchovy, and sardines all showed high overlap with the two jellyfish species, with all values near or above the 60% PSI that indicates high overlap (Table 2). The two smelt species had low or intermediate diet overlaps (around 14–21%), whereas the salmon species and jack mackerel had very low (1–3%) PSI values, and therefore were not judged to be competing trophically.

Diet overlap as determined by PSI was similar to patterns observed in stable isotope analysis of multiple trophic levels (Fig. 4). C. fuscescens and A. labiata occupied the same general trophic level, with C. fuscescens deriving more of its food from inshore sources (higher δ13C), consistent with its inner-shelf spatial distribution (Suchman and Brodeur 2005). Herring, saury, anchovy and sardines fed at a higher level than the medusae, but were still considered at the same trophic level in the food web (i.e., <3.4 δ15 N value; Post 2002). The carbon isotope ratios further suggest some inshore-offshore partitioning of food resources, with herring and anchovy feeding further inshore than sardines and saury, again consistent with their spatial distributions (Fig. 4). The remaining fish species examined here were feeding at a higher trophic level than these four pelagic fishes and medusae.

Potential for competitive interactions

Among the species we examined for spatial and trophic overlap, we found several intermediate spatial overlaps and some high trophic overlaps. An overlap index (OI) was calculated for each species by taking the equally weighted arithmetic mean of the spatial and trophic indices, with relatively high values corresponding to the most potential for interspecific competition. Table 3 indicates the nekton species likely to be most affected by co-occurrence with each jellyfish species, and these are displayed graphically in Fig. 5. Perfect spatial and dietary overlap yields a value of one, which would likely lead to competitive exclusion, whereas no spatial nor dietary overlap yields a value of zero. Higher index values thus indicate greater potential for competition between the species.

Chrysaora fuscescens had considerable spatial and dietary overlap with whitebait smelt, Pacific herring, northern anchovy, and Pacific sardine, and consequently the greatest OI values for potential competitive interactions (Table 3). OI values were moderately high for juvenile Chinook salmon, juvenile coho salmon, and Pacific saury; however, given the low overlap for either diet or space with each species, it is unlikely that these species would be strong competitors. Similarly, several fish species had moderate to high OI values with A. labiata (Table 3). Nekton species with the greatest potential for being competitors with A. labiata were surf smelt, Pacific herring, and Pacific saury, which all showed substantial spatial and dietary overlaps. Northern anchovies and Pacific sardines also showed moderate OI values. However, the amount of spatial overlap with A. labiata was low for these two nekton species, indicating that during August 2002, strong competition between the species was unlikely. Although no species pairing had higher than 50% overlap for both measures (upper right quadrants in Fig. 5), Pacific herring are at the greatest risk of competition and likely to be affected most by increased biomass of these two jellyfish species.

Discussion

Although some effort has been expended to examine factors underlying the increased occurrence and magnitude of blooms of gelatinous zooplankton in recent years (Mills 2001; Parsons and Lalli 2002; Purcell 2005; Purcell et al. 2007), there have been few attempts to examine ecosystem consequences of the proliferation of jellyfish in many parts of the world. Purcell and Sturdevant (2001) analyzed the juvenile diets of four forage fish species and four gelatinous zooplankton species in a similar manner to our study. Unfortunately their fish and jellyfish samples were not collected in the same year so spatial overlap could not be assessed. They found that diet overlaps between the fish and jellyfish averaged around 50% overall, but some species pair overlaps were close to 80% (Purcell and Sturdevant 2001). Our comparisons of the food resources used by pelagic fish and the abundant jellyfish species were made from individuals collected in the same area and time frame and our results confirmed that there is a potential for trophic competition between fish and jellyfish in this system.

Based on what is known about feeding mechanisms in these species, it is not surprising that jellyfish and the more zooplanktivorous fishes had high dietary overlaps. Large scyphomedusae in this ecosystem swim continuously and capture prey that come in contact with nematocysts, which are either embedded in short tentacles fringing the bell margin (A. labiata) or trail up to several meters beyond the organism’s pulsing bell (C. fuscescens). For cruising, entangling predators such as medusae, the encounter zone vis a vis potential prey will depend upon tentacle placement and extent and bell size; thus this zone is dynamic and based upon medusan swimming rate (Madin 1988). Previous studies of interactions between scyphomedusae and zooplankton have suggested that in general, larger, slow-escaping prey will be most vulnerable (e.g. Suchman and Sullivan 2000) and are more readily entrained in the flow created by a swimming medusa (Costello and Colin 1994). Diets observed in this study support this hypothesis, with passively drifting or relatively slow-moving prey taxa (early stages of euphausiids, gelatinous zooplankton, cladocerans) making up a high proportion of prey ingested by medusae and fast-escaping prey such as copepods a smaller proportion of medusan diets. In contrast, pelagic fishes such as sardines and anchovies are generally cruising planktivores, ranging between nonvisual filter feeders and particulate microplanktonic feeders, while juvenile salmon and jack mackerel are selective planktivorous or piscivorous predators (Greene 1985; Schabetsberger et al. 2003).

Our available data were limited in space and time and therefore we cannot say with certainty that diets observed during August 2002 are typical. Although collections were available from four major surveys in this study region that quantified both jellyfish and pelagic fishes (Suchman and Brodeur 2005), we were not able to make collections for diet analysis of jellyfish during most of these. Because of the potential for net feeding and especially regurgitation in jellyfish caught in a trawl, we had to limit our stomach analysis to collections made with a dip net from the side of a vessel (Suchman et al. 2008). Stomach analyses of many pelagic fish predators that we examined from other cruises do show substantial interannual and seasonal variation, but none exhibited a high consumption of euphausiid eggs (Miller and Brodeur 2007).

The type and amount of prey eaten by these abundant jellyfish are likely to impact the critical prey resources that support the pelagic fishes of the California Current ecosystem. During August 2002, the jellyfish C. fuscescens alone was estimated to consume an average of 32% and up to 60% of the standing stock of euphausiid eggs daily in nearshore stations, where medusae are most abundant (Suchman et al. 2008). Collections at two stations in 2003 showed no euphausiid eggs in the prey field or diet, so interannual variability in feeding by medusae is likely as well (Suchman et al. 2008). Nevertheless, collections of euphausiid eggs with plankton nets from 1996 to 2005 off Newport, OR, suggested that 2002 was a typical year in terms of egg abundance (Peterson et al. 2006). In addition to factors such as advection, survival of early stage euphausiids may be related to predation pressure, which varies with size and location of predator and prey populations.

Despite the fact that our diet analyses were limited to one cruise, observed trophic overlaps were reinforced by the stable isotope analysis, which integrates over longer time periods [several months for δ15 N in adult Pacific herring (Miller 2006b)]. This provided some confidence that results regarding diet and habitat made during one cruise can be extended to other periods. However, a widespread hypoxic zone developed in one region of the Oregon shelf during summer 2002 (Grantham et al. 2004) and may have modified habitat suitability. Many scyphomedusae and other gelatinous zooplankton are highly tolerant of low oxygen conditions (Purcell et al. 2001b; Rutherford and Thuesen 2005; Thuesen et al. 2005) and may be at a competitive feeding advantage compared to pelagic fishes in hypoxic waters (Shoji et al. 2005). More recent sampling from the Oregon coast has shown that this hypoxic zone has broadened geographically, extended closer to the surface, and may be a recurring event in summer months (Chan et al. 2008), which would imply changing habitat dynamics that favor jellyfish over fish.

Station-only data is expected to yield low overlap values, especially if the nekton species are avoiding areas with jellyfish. Our data do not allow us to definitively state if the nekton are avoiding these locations because of the presence of jellyfish or because those locations are simply not preferred habitat. It is also possible that simply a patch of fish was not detected or missed by our sampling method. The geostatistical technique is therefore preferred because it is an ideal method when working with moderately patchy distributions. This method provided maps of the likely areas one could reasonably expect to find the nekton and jellyfish which allowed us to then examine the degree of spatial overlap of these predicted distributions.

Resource competition implies that the shared resource is in limited quantity. It is likely that both food and habitat are limiting during at least part of the year, so potential for competition is high. The intensity of competition may vary depending upon the distribution and quantity of the resources in space and time, in addition to the relative foraging and exclusion abilities of the competitors. An alternate form of competition is indirect or “interference” competition (Case and Gilpin 1974) where instead of directly utilizing food that a fish predator would otherwise consume, dense aggregations of the competitor, such as jellyfish, with their long extending tentacles, could totally occupy a particular suitable habitat. Thus many pelagic fishes may actively avoid these nearshore regions, thereby excluding themselves from that habitat and access to the food resources therein. Field and laboratory studies have shown that “interference” competition may be more prevalent than the widely assumed “exploitation” competition (Case and Gilpin 1974; Branch 1984). Based upon multivariate community analyses from this cruise (Reese 2005), the only fishes found more closely associated with A. labiata than the forage fishes examined here were those likely to be commensal with jellies, such as medusafish (Icichthys lockingtoni) and ragfish (Icosteus aenigmaticus); no adult fish were found in close association with C. fuscescens. Although these observations are strictly correlative and not direct evidence for “interference” competition, the potential exists for jellyfish blooms to displace pelagic fish from some suitable habitat areas due to their sheer biomass in coastal waters.

Although long-term data on biomass trends are not available for the Northern California Current, recent increases in other systems attributable to ocean warming, coupled with predicted long-term climate trends, suggest that some coastal ecosystems will see more jellyfish in the future (Attrill et al. 2007). Moreover, since gelatinous zooplankton are known to be major consumers of early life stages of many fish species, these systems are not likely to revert to being fish-dominated once again unless acted upon by another major perturbation that is less favorable for jellyfish recruitment (e.g., Bakun and Weeks 2006). Although our analyses of the diets of the dominant large jellyfish did not reveal substantial predation on early life stages of fish, the late summer period of our sampling is generally a time of minimal ichthyoplankton densities off Oregon (Brodeur RD, unpublished data) and jellyfish predation on fish, if occurring, is probably more important in the spring and early summer.

Our results suggest that an increase of jellyfish in this system could have profound negative impacts on several commercially and ecologically important components of the ecosystem. Such impacts are difficult to assess in field situations without the benefit of controlled experimentation. A mass-balance ecosystem model that has recently been developed specifically addressed the complex interactions among the key ecosystem components (Ruzicka et al. 2007). Results from model runs parameterized for early and late summer suggested that jellyfish have a lower impact on plankton populations than pelagic fishes in spring but by late summer, jellyfish became the dominant zooplankton consumers in the system consuming almost twice as much zooplankton production as forage fishes (Ruzicka et al. 2007). Moreover, relatively little of the jellyfish biomass is passed on to higher trophic levels compared with forage fishes, so jellyfish consumption of zooplankton could divert energy from more traditional fisheries. As marine fisheries serially deplete top predators in the world’s oceans and turn to exploiting resources much lower in the food web (Pauly et al. 1998; Essington et al. 2006), factors such as competition with increasing gelatinous zooplankton populations may affect the status of many forage species in the ecosystem limiting their overall production. Our findings support the premise that examination of alternative trophic pathways is needed in fisheries management.

References

Arai MN (1988) Interactions of fish and pelagic coelenterates. Can J Zool 66:1913–1927

Arai MN (2001) Pelagic coelenterates and eutrophication: a review. Hydrobiology 451:69–87

Atkinson A, Siegel V, Pakhomov E, Rothery P (2004) Long-term decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean. Nature 432:100–103

Attrill MJ, Wright J, Edwards M (2007) Climate-related increases in jellyfish frequency suggest a more gelatinous future for the North Sea. Limnol Oceanogr 52:480–485

Bakun A, Weeks SJ (2006) Adverse feedback sequences in exploited marine systems: are deliberate interruptive actions warranted? Fish Fish 7:316–333

Branch GM (1984) Competition between marine organisms: ecological and evolutionary implications. Oceanogr Mar Biol Ann Rev 22:429–593

Brodeur RD, Mills CE, Overland JE, Walters GE, Schumacher JD (1999) Substantial increase in gelatinous zooplankton in the Bering Sea, with possible links to climate change. Fish Oceanogr 8:296–306

Brodeur RD, Sugisaki H, Hunt GL Jr (2002) Increases in jellyfish biomass in the Bering Sea: implications for the ecosystem. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 233:89–103

Case TJ, Gilpin ME (1974) Interference competition and niche theory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71:3073–3077

Chan F, Barth JA, Lubchenco J, Kirincich A, Weeks H, Peterson WT, Menge BA (2008) Emergence of anoxia in the California Current large marine ecosystem. Science 319:920

Chiles J-P, Delfiner P (1999) Geostatistics: modeling spatial uncertainty. Wiley, New York

Costello JH, Colin SP (1994) Morphology, fluid motion, and predation by the scyphomedusa Aurelia aurita. Mar Biol 121:327–334

Cressie NAC (1993) Statistics for spatial data. Wiley, New York

Emmett RL, Brodeur RD, Miller TW, Pool SS, Bentley PJ, Krutzikowsky GK, McCrae J (2005) Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax) abundance, distribution and ecological relationships in the Pacific Northwest. Calif Coop Oceanic Fish Invest Rep 46:122–143

Essington TE, Beaudreau AH, Wiedenmann J (2006) Fishing through marine food webs. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103:3171–3175

Fancett MS, Jenkins GP (1988) Predatory impact of scyphomedusae on ichthyoplankton and other zooplankton in Port Phillip Bay. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 116:63–77

Graham WM, Bayha KM (2007) Biological invasions by marine jellyfish. In: Nentwig W (ed) Ecological studies, vol 193, biological invasions. Springer, Berlin, pp 240–255

Grantham BA, Chan F, Nielsen KJ, Fox DS, Barth JA, Huyer J, Lubchenco J, Menge BA (2004) Upwelling-driven nearshore hypoxia signals ecosystem and oceanographic changes in the northeast Pacific. Nature 429:749–754

Greene CH (1985) Planktivore functional groups and patterns of prey selection in pelagic communities. J Plankton Res 7:35–40

Johnston K, Ver Hoef JM, Krivoruchko K, Lucas N (2001) Using ArcGIS geostatistical analyst. ESRI, California

Link JS, Ford MD (2006) Widespread and persistent increase of Ctenophora in the northeast US shelf ecosystem. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 320:153–159

Lynam CP, Brierley AS (2007) Enhanced survival of 0-group gadoid fish under jellyfish umbrellas. Mar Biol 150:1397–1401

Lynam CP, Hay SJ, Brierley AS (2004) Interannual variability in abundance of North Sea jellyfish and links to the North Atlantic oscillation. Limnol Oceanog 49:637–643

Lynam CP, Hay SJ, Brierley AS (2005) Jellyfish abundance and climatic variation: contrasting responses in oceanographically distinct regions of the North Sea, and possible implications for fisheries. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 85:435–450

Lynam CP, Gibbons MJ, Axelsen BE, Sparks CAJ, Coetzee J, Heywood BG, Brierley AS (2006) Jellyfish overtake fish in a heavily fished ecosystem. Curr Biol 16:R492–R493

Madin LP (1988) Feeding behavior of tentaculate predators: in situ observations and a conceptual model. Bull Mar Sci 43:413–429

Matheron G (1971) The theory of regionalized variables and its applications. Les Cahiers du Centre de Morphologie Mathématique, Fascicule 5, Centre de Géostatistique, Fontainebleau

Miller TW (2006a) Trophic dynamics of marine nekton and zooplankton in the northern California Current pelagic ecosystem. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, 212 p

Miller TW (2006b) Tissue-specific response of δ15 N in adult Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi) following an isotopic shift in diet. Environ Biol Fish 76:177–189

Miller TW, Brodeur RD (2007) Diet of and trophic relationships among dominant marine nekton within the northern California Current ecosystem. Fish Bull 105:548–559

Mills CE (2001) Jellyfish blooms: are populations increasing globally in response to changing ocean conditions? Hydrobiologia 451:55–68

Möller H (1984) Reduction of a larval herring population by jellyfish predator. Science 224:621–622

Mullon C, Fréon P, Cury P (2005) The dynamics of collapse in world fisheries. Fish Fish 6:111–120

Parsons TR, Lalli CM (2002) Jellyfish population explosions: revisiting a hypothesis of possible causes. La Mer 40:111–121

Pauly D, Christensen V, Dalsgaard J, Froese R, Torres R Jr (1998) Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279:860–863

Peterson WT et al. (2006) The state of the California Current, 2005–2006: warm in the north, cool in the south. Calif Coop Oceanic Fish Invest Rep 47:30–74

Post DM (2002) Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 83:703–718

Purcell JE (1985) Predation on fish eggs and larvae by pelagic cnidarians and ctenophores. Bull Mar Sci 37:739–755

Purcell JE (1989) Predation on fish larvae and eggs by the hydromedusa Aequorea victoria at a herring spawning ground in British Columbia. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 46:1415–1427

Purcell JE (1990) Soft-bodied zooplankton predators and competitors of larval herring (Clupea harengus pallasi) at herring spawning grounds in British Columbia. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 47:505–515

Purcell JE (2005) Climate effects on formation of jellyfish and ctenophore blooms. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 85:461–476

Purcell JE, Arai MN (2001) Interactions of pelagic cnidarians and ctenophores with fish: a review. Hydrobiologia 451:27–44

Purcell JE, Decker MB (2005) Effects of climate on relative predation by schyphomedusae and ctenophores on copepods in Chesapeake Bay during 1987–2000. Limnol Oceanogr 50:376–387

Purcell JE, Sturdevant MV (2001) Prey selection and dietary overlap among zooplanktivorous jellyfish and juvenile fishes in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 210:67–83

Purcell JE, Nemazie DA, Dorsey SE, Houde ED, Gamble JC (1994) Predation mortality of bay anchovy Anchoa mitchelli eggs and larvae due to schyphomedusae and ctenophores in Chesapeake Bay. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 114:47–58

Purcell JE, Malej A, Benovi A (1999) Potential links of jellyfish to eutrophication and fisheries. In: Ecosystems at the land-sea margin: drainage basin to Coastal Sea. Coastal and Estuarine Studies 55:241–263

Purcell JE, Graham WM, Dumont HJ (2001a) Jellyfish blooms: ecological and societal importance. Developments in hydrobiology, vol 155. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Purcell JE, Breitburg DL, Decker MB, Graham WM, Youngbluth MJ, Raskoff KA (2001b) Pelagic cnidarians and ctenophores in low dissolved oxygen environments: a review. In: Rabalais NN, Turner RE (eds) Coastal hypoxia: consequences for living resources and ecosystems. American Geophysical Union, Washington DC, Coastal and Estuarine Studies 58:77–100

Purcell JE, Uye S, Lo W-T (2007) Anthropogenic causes of jellyfish blooms and their direct consequences for humans: a review. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 350:152–174

Reese DC (2005) Distribution, structure, and function of marine ecological communities in the northern California Current upwelling ecosystem. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, 258 p

Reese DC, Brodeur RD (2006) Identifying and characterizing biological hotspots in the Northern California Current. Deep Sea Res II 53:291–314

Reese DC, Miller TW, Brodeur RD (2005) Community structure of near-surface zooplankton in the northern California Current in relation to oceanographic conditions. Deep Sea Res II 52:29–50

Rutherford LD Jr, Thuesen EV (2005) Metabolic performance and survival of medusae in estuarine hypoxia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 294:189–200

Ruzicka JJ, Brodeur RD, Wainwright TC (2007) Seasonal food web models for the Oregon inner-shelf ecosystem: investigating the role of large jellyfish. Calif Coop Oceanic Fish Invest Rep 48:106–128

Schabetsberger R, Morgan CA, Brodeur RD, Potts CL, Peterson WT, Emmett RL (2003) Prey selectivity and diel feeding chronology of juvenile chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and coho (O. kisutch) salmon in the Columbia River plume. Fish Oceanogr 12:523–540

Shenker JM (1984) Scyphomedusae in surface waters near the Oregon coast, May–August 1981. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 19:619–632

Shiganova TA (1998) Invasion of the Black Sea by the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and recent changes in pelagic community structure. Fish Oceanogr 7:305–310

Shiganova TA, Bulgakova YV (2000) Effects of gelatinous plankton on Black Sea and Sea of Azov fish and their food resources. ICES J Mar Sci 57:641–648

Shoji J, Masuda R, Yamashita Y, Tanaka M (2005) Effect of low dissolved oxygen concentrations on behavior and predation rates of red sea bream Pagrus major larvae by the jellyfish Aurelia aurita and by juvenile Spanish mackerel Scomberomorus niphonius. Mar Biol 147:863–868

Suchman CL, Brodeur RD (2005) Abundance and distribution of large medusae in surface waters of the northern California Current. Deep Sea Res II 52:51–72

Suchman CL, Sullivan BK (2000) Effect of prey size on vulnerability of copepods to predation by the scyphomedusae Aurelia aurita and Cyanea sp. J Plankton Res 22:2289–2306

Suchman CL, Daly EA, Keister JE, Peterson WT, Brodeur RD (2008) Feeding patterns and predation potential of scyphomedusae in a highly productive upwelling region. Mar Ecol Prog Ser (in press)

Thuesen EV, Rutherford LD Jr, Brommer PL, Garrison K, Gutowska MA, Towanda T (2005) Intragel oxygen promotes hypoxia tolerance of scyphomedusae. J Exp Biol 208:2475–2482

Wallace HJ, Ramsay S (1983) Reliability in measuring diet overlap. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 40:347–351

Xian W, Kang B, Liu R (2005) Jellyfish blooms in the Yangtze Estuary. Science 307:41

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to S. Pool (Oregon State University) for help on the database management, Drs. Chris Harvey and Ed Casillas (NWFSC, NMFS), Jennifer Purcell (Sea Pen Scientific Writing LLC), and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. Funding was provided by the US GLOBEC Northeast Pacific Program and the Bonneville Power Administration. This is GLOBEC Contribution number 592.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by B.S. Stewart.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brodeur, R.D., Suchman, C.L., Reese, D.C. et al. Spatial overlap and trophic interactions between pelagic fish and large jellyfish in the northern California Current. Mar Biol 154, 649–659 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-008-0958-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-008-0958-3