Abstract

Discontinuation of denosumab (DMab) is associated with decline in bone density. Whether raloxifene can be effective to attenuate bone loss after DMab discontinuation in certain conditions when other antiresorptives cannot be used remains unclear. Data on postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who discontinued DMab treatment after short-term use (1-to-4 doses) at Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea, between 2017 and 2021 were reviewed. Changes in bone mineral density (BMD) at 12 months after DMab discontinuation was compared between sequential raloxifene users (DR) and those without any sequential antiresorptive (DD) after 1:1 propensity score matching. In matched cohort (66 patients; DR n = 33 vs. DD n = 33), mean age (69.3 ± 8.2 years) and T-score (lumbar spine − 2.2 ± 0.7; total hip − 1.6 ± 0.6) did not differ between two groups at the time of DMab discontinuation. Sequential treatment to raloxifene in DR group attenuated the bone loss in lumbar spine after DMab discontinuation compared to DD group (DR vs. DD; − 2.8% vs. − 5.8%, p = 0.013). The effect of raloxifene on lumbar spine BMD changes remained robust (adjusted β + 2.92 vs. DD, p = 0.009) after adjustment for covariates. BMD loss at femoral neck (− 1.70% vs. − 2.77%, p = 0.673) and total hip (− 1.42% vs. − 1.44%, p = 0.992) did not differ between two groups. Compared to BMD at DMab initiation, DR partially retained BMD gain by DMab treatment in lumbar spine (+ 3.7%, p = 0.003) and femoral neck (+ 2.8%, p = 0.010), whereas DD did not. Raloxifene use after DMab treatment attenuated lumbar spine BMD loss in postmenopausal women with short exposures (< 2 years) to DMab.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Denosumab (DMab), a humanized anti-RANKL monoclonal antibody, is a potent antiresorptive agent that reduces fracture risk effectively and exhibits long-term efficacy and safety [1, 2]. Recent clinical guidelines endorsed the use of DMab as one of the first-line anti-osteoporosis medication in patients with a high risk of fracture [3, 4]. However, unlike bisphosphonates, several studies have reported the reversal of DMab’s effect after its discontinuation, causing rapid bone loss and increasing immediate fracture risk [5,6,7]. To overcome this drawback, sequential administration of bisphosphonate or continuation of DMab is recommended currently as a standard treatment based on the data from randomized clinical trials [8,9,10].

Raloxifene is an antiresorptive agent recommended as second line treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis, particularly when drugs such as bisphosphonate and DMab are not suitable for use [3, 11, 12]. There is insufficient data on the effect of sequential raloxifene treatment after DMab discontinuation on changes in bone mineral density (BMD) or bone fracture [13]. We hypothesized that the partial attenuation of BMD loss facilitated by raloxifene therapy may provide an alternate approach in limited clinical circumstances when the sequential treatment with bisphosphonate or DMab continuation are not applicable in postmenopausal women. However, randomized trials to test this hypothesis might not be feasible due to practical and ethical issues.

In this propensity score-matched, observational, proof-of-concept study using real-world data, we examined the effect of raloxifene use after DMab discontinuation on changes in BMD compared to patients who discontinued DMab without a sequential antiresorptive therapy due to various reasons.

Methods

Study Subjects

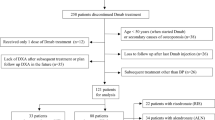

Data on postmenopausal women initiated with DMab therapy (60 mg subcutaneous injection for every 6 months) between 2017 and 2019, followed by raloxifene 60 mg daily or discontinuation of DMab without any treatment for 1 year at Severance Hospital, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea (n = 94), were retrieved from Severance Clinical Data Repository System (Fig. 1). All subjects received DMab injections (at least one dose, up to four doses) during the study period. After excluding data of subjects showing absence of BMD at baseline or follow-up (n = 2), DMab followed by raloxifene treatment group (DR; n = 51) and DMab discontinuation without any treatment group (DD; n = 41) were 1:1 matched using propensity score matching based on factors such as age, body mass index (BMI), lumbar spine and total hip BMD at the time of DMab discontinuation, total number of DMab injection, and the use bisphosphonate within 2 years prior to DMab initiation. After matching, a total of 66 subjects (DR, n = 33; DD, n = 33) were present in final cohort. This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, with a waiver of written consent since the study design was based on retrospective medical record review (IRB No. 4-2021-1346).

Bone Mineral Density Measurements

All BMD measurements of lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip were performed using a single dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Discovery W, Hologic, Inc.; NH, USA) at before DMab initiation, baseline (time of DMab discontinuation), and follow-up (1 year after DMab discontinuation; Supplementary Fig. 1) in the Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea. Coefficients of variation for lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip were 1.2%, 2.1%, and 1.7%, respectively. Changes in BMD at lumbar spine (%) between baseline and follow-up was the primary outcome of the study. BMD data at the time of DMab initiation were available in a subset of matched pairs of study subjects (DR, n = 27; DD, n = 27) for the extension analysis. T-score was calculated by third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, using data of young white female as reference [14].

Covariates

Height and weight were measured at DXA testing room using automated digital stadiometer. Previous fracture history was obtained using diagnosis codes and medical records with X-ray images review. Bisphosphonate exposure within 2 years prior to DMab initiation was defined by reviewing hospital drug claim database and medical records. Serum calcium, phosphate, and creatinine were measured using Hitachi chemistry autoanalyzer 7600-110 (Hitachi Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) at the central laboratory of Severance Hospital. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were determined using a radioimmunoassay (RIA; DiaSorin, Inc.; Stillwater, MN, USA; intraassay CV < 4.1%, interassay CV < 7.0%). Reasons of raloxifene sequential treatment or discontinuation of DMab were reviewed based on medical records, which was later grouped into four categories (recent or planned invasive dental procedure; ineligible to get financial reimbursement from national health insurance due to improved BMD after DMab treatment; refused sequential bisphosphonate due to fear of any acute or chronic complications; and other unknown reason). Serum C-terminal telopeptide (CTX; Elecsys β‐CrossLaps; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany; intraassay CV < 3.5%, interassay CV < 8.4%) and procollagen type 1N-terminal propeptide (P1NP; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany; intraassay CV < 3.6%, interassay CV < 3.9%) at baseline and follow-up were available in a subset of subjects (n = 32).

Vertebral Fracture Assessment

Vertebral fracture after DMab discontinuation was assessed in all patients using clinical investigation for newly developed back pain for each visit. Systemic spine X-ray or DXA vertebral fracture assessment at the time of DXA testing at baseline (time of DMab discontinuation) and follow-up (1 year after DMab discontinuation) were available in 40 subjects (40/66, 60.6%). Newly developed vertebral fracture after DMab discontinuation was defined as grade 2 or higher vertebral fracture using semiquantitative Genant method with newly developed back pain (clinical vertebral fracture) or without any documented clinical symptoms (morphometric vertebral fracture) based on review of medial record and spine images [15].

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range] for continuous variables and numerical value (%) for categorical variables. Independent two-sample t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and χ2 test were used to compare baseline characteristics of study subjects as appropriate. We performed PSM between DR and DD groups using nearest-neighbor algorithm within specified caliper width (0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score) on 1:1 basis without replacement. Propensity score was calculated based on age, BMI, BMD of lumbar and total hip, number of DMab injection, and bisphosphonate use prior to DMab treatment. Covariate balance was assessed using standardized bias with a threshold of 20% to determine substantial imbalance (Supplementary Fig. 2). Changes in BMD (%) at follow-up were compared between DR and DD groups using independent two-sample t-test. Differences in bone turnover markers at baseline and follow-up were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test within each group. Independent effect of raloxifene use on BMD changes of lumbar spine were estimated using multivariable linear regression analysis. In an extension subset to evaluate trajectory of BMD from DMab initiation to follow-up, effects of sequential raloxifene treatment after DMab discontinuation on BMD (%, BMD at DMab initiation as reference) at each time point were assessed using linear mixed model with adjustment for covariates. The study sample size (33 subjects for each DR and DD group) achieved 73% power to detect observed difference in BMD changes in the lumbar spine between the two groups at an α of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 16.1 (Stata Corp., TX, USA). Statistical significance level was set at two-sided p value < 0.05.

Results

Clinical Characteristics of Study Subjects

In propensity score-matched cohort (DR, n = 33; DD, n = 33; Fig. 1), the mean age was 69.3 ± 8.2 years and T-score of lumbar spine and total hip was − 2.2 ± 0.7 and − 1.6 ± 0.6, respectively, at the time of DMab discontinuation. In overall unmatched subjects, the DR group had lower BMI and T-scores at lumbar spine and total hip compared to those of the DD group (Supplementary Table 1). After PSM based on age, BMI, BMD of lumbar spine and total hip, DMab injection numbers, and prior bisphosphonate exposure, all matched variables did not show significant differences between DR and DD (Table 1) with the reduction of standardized bias to less than the prespecified imbalance threshold after matching (Supplementary Fig. 2). The most common reason for sequential raloxifene treatment was preplanned invasive dental surgery (n = 18, 55%), whereas the most common reason for DMab discontinuation without any sequential treatment was ineligibility to obtain insurance reimbursement in patients with BMD at non-osteoporotic range (n = 18, 55%), followed by refused bisphosphonate use due to fear of complications (n = 9, 27%).

Effect of Raloxifene on BMD After DMab Discontinuation

In overall matched cohort, BMD at 12 months follow-up after DMab discontinuation decreased significantly in all sites including lumbar spine (− 4.3%, 95% CI − 5.5 to − 3.0, p < 0.001), femoral neck (− 2.0%, 95% CI − 3.3 to − 0.7, p = 0.004), and total hip (− 1.4%, − 2.8 to − 1.0, p = 0.035). Sequential treatment of raloxifene in DR group attenuated the bone loss in lumbar spine after DMab discontinuation compared to that in DD group (DR vs. DD; − 2.8% vs. − 5.8%, p = 0.013; Fig. 2). Difference in BMD changes did not reach statistical significance at femoral neck (− 1.7% vs. − 2.3%, p = 0.673) and total hip (− 1.4% vs. − 1.4%, p = 0.992). The effect of raloxifene on BMD changes in lumbar spine remained independent (adjusted β + 2.92 vs. DD, 95% CI 0.75 to 5.10, p = 0.009) in multivariable model after adjustment for age, BMI, previous fracture, lumbar spine T-score, bisphosphonate use prior to DMab initiation, and DMab injection times (Table 2). Younger age (adjusted β − 0.21 per 1-year younger, p = 0.004) and previous history of fracture (adjusted β − 4.29, p = 0.003) were independent predictors of bone loss after DMab discontinuation. No incident clinical or morphometric vertebral fracture was noted during the follow-up period in all subjects in both DD and DR groups. However, one radius fracture in DD group was observed at 7 months after DMab discontinuation.

Changes in Bone Turnover Markers

Bone turnover markers were available at baseline and follow-up in a subset of study subjects (DD group, n = 8; DR group, n = 24). Bone turnover markers were measured simultaneously at the time of DXA testing (Supplementary Fig. 1). Serum CTx and P1NP significantly increased at follow-up in both DD group (CTx, median 0.144 to 0.379 ng/mL; P1NP, 24.6 to 50.9 ng/mL) and DR group (CTx, median 0.073 to 0.363 ng/mL; P1NP, 15.7 to 40.9 ng/mL; p < 0.05 for all; Supplementary Fig. 3). However, the magnitude of changes in CTx (+ 0.255 and + 0.251 ng/mL in DD and DR, p = 0.760) and P1NP (+ 25.8 and + 25.4 ng/mL, p = 0.761) did not differ between DD and DR groups.

BMD Changes from DMab Initiation to Follow-up

BMD measurements at the time of DMab initiation, discontinuation, and follow-up were available in 54 matched subjects (DR, n = 27 vs. DD, n = 27). Baseline BMD did not differ between DR and DD groups for lumbar spine (DR vs. DD; T-score − 2.7 vs. − 2.8), femoral neck (− 2.3 vs. − 2.2), and total hip (− 1.9 vs. − 1.8). When BMD at DMab initiation was set as reference value, BMD at all sites increased at the time of DMab discontinuation (DR vs. DD; lumbar spine + 6.7% vs. + 7.3%; femoral neck + 4.9% vs. + 2.9%; and total hip + 3.2% vs. + 3.7%; p < 0.05 compared to baseline in each group), without significant difference between groups (Fig. 3). At 12 months follow-up period after DMab discontinuation, sequential raloxifene treatment partially retained bone gain caused during DMab treatment for lumbar spine, whereas BMD level in the DD group decreased to the BMD level seen during DMab initiation with significant group differences in linear mixed model adjusted for covariates (DR vs. DD; BMD at follow-up compared to DMab initiation; + 3.7% vs. + 0.8%, p = 0.018). At femoral neck, DR group partially preserved gain in BMD obtained during DMab treatment as compared to DMab initiation (+ 2.8%, p = 0.010), whereas DD group did not (+ 0.6%, p = 0.454).

Discussion

Here, we found that sequential raloxifene treatment after DMab discontinuation partially attenuated BMD loss for lumbar spine compared to absence of treatment in propensity score-matched cohort of postmenopausal women. Although significant BMD loss was observed in both DR and DD groups after DMab discontinuation, DR group showed partial preservation of gain in BMD obtained during DMab treatment for lumbar spine and femoral neck. Raloxifene use was associated with BMD protection in lumbar spine in the multivariable regression model after adjustment for covariates.

BMD loss followed by DMab discontinuation was reported in a phase 2 trial for DMab [16]. For lumbar spine and total hip, 6.6% and 5.3% loss, respectively, were observed after DMab discontinuation in 51 postmenopausal women; this loss was reversed after DMab re-administration [16]. Similar to previous findings, we observed that DD group lost most of BMD (6.5% in lumbar spine, 1.4% in total hip) which was later gained during DMab treatment period at all measured sites.

Previous studies showed that bisphosphonate was effective in preserving BMD after DMab discontinuation [17, 18]. Oral alendronate showed a BMD gain of 0 to 1% in switching patients after one year of DMab use in DMab Adherence Preference Satisfaction study [17]. Zoledronic acid protected about 66% of the lumbar spine gain in BMD in patients switched after using DMab for an average of 3 years [18]. Significant bone loss was observed in long-term DMab users compared to short-term users (2.5 years or less) [19, 20]. Based on the evidence, European Society guideline endorsed the use of either oral alendronate or intravenous zoledronic acid for short-term users and zoledronic acid for long-term users to protect bone loss after DMab therapy [19]. In the case of raloxifene, a study compared the effect of use of bisphosphonate at the time of discontinuation of DMab. In this study, patients taking oral bisphosphonate or using teriparatide before DMab were included, and the average number of DMab doses was 2.6. After DMab discontinuation, the study was conducted with the raloxifene group (n = 13) and the bisphosphonate group (n = 40). BMD values were compared during the last date of DMab administration and 1.5 years after the final DMab therapy. In the raloxifene group, the bone loss occurred in 2.7% in the lumbar spine and 3.8% in the femur neck. Bisphosphonate showed better femur neck BMD preservation than raloxifene group [13]. Based on these results, the ECTS guideline stated selective estrogen receptor modulator as non-promising and warrants additional data [19]. Similar to prior study, we observed 2.8% bone loss in the lumbar spine. However, when compared to DMab initiation as reference time point, overall partial retainment of bone gain by DMab treatment was noted compared to non-treatment group in our findings. Rebound effect after DMab discontinuation in bone turnover markers was observed in both groups that serum CTx and P1NP significantly increased at follow-up in both DD and DR group. Despite the partial preservation of BMD at lumbar spine in DR group, raloxifene treatment after DMab discontinuation did not effectively suppress the elevation of bone turnover markers compared to non-treatment group in this study. However, given the relatively short-term use of DMab and limited sample size in this study, this finding needs to be examined in future studies.

Prior studies revealed anti-fracture efficacy and improvement in BMD by raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator with antiresorptive action, particularly for lumbar spine at trabecular-bone rich site [11, 21]. Although the gain in BMD by raloxifene in postmenopausal osteoporosis was smaller than that by other antiresorptive drugs such as bisphosphonate or DMab, reports suggest that robust decrease in vertebral fracture rate in raloxifene users compared to relatively small gain in BMD can be contributed to improvement in bone quality such as bone microstructure [22, 23]. Due to relatively weak antiresorptive properties and reversal action, better safety profile of raloxifene compared to bisphosphonate was proposed in previous studies. The safety profile was based on rare chronic complications of antiresorptive agents such as medication-related osteonecrosis of jaw or atypical femoral fracture [24, 25]. Although the efficacy to prevent bone loss might be lower than previously reported efficacy of bisphosphonate, these data support the use of raloxifene as second line agent to reduce fracture risk when bisphosphonate cannot be used due to various clinical or administrative causes in real-world clinical setting. Our data may provide a proof-of-concept level evidence to support the strategy for utilizing raloxifene as second line therapy following discontinuation of short-term DMab when bisphosphonate is not applicable. However, this hypothesis needs to be further validated in larger trials.

In our real-world data, common reasons to discontinue DMab without bisphosphonate treatment was invasive dental surgery, ineligible to obtain reimbursement in osteopenic range, and refusal to bisphosphonate due to fear of rare complications. Previous studies reported several reasons for DMab discontinuation. In a report summarizing several observational studies, the most common reason for discontinuing DMab was that the target T-score reached outside the region of osteoporosis [26]. Furthermore, although the risk is low, osteonecrosis of the jaw or atypical fracture may occur. Hence, the risk–benefit ratio can favor the decision to stop the treatment [27, 28]. In a recently published retrospective chart review analyzing 797 DMab users, the reasons for termination of treatment were a considerable increase in BMD (31.9%) and the occurrence of side effects (10%) [29]. The fear of rare complications of bisphosphonate remains in clinical practice, indicating the need for patient’s understanding to compare the risk and benefit ratio of bisphosphonate treatment based on evidence [30]. Because South Korea has universal, mandatory national insurance system to all Koreans, reimbursement policy of health insurance reimbursement agency has a huge impact on clinical practice at an individual level. Because current policy mandates BMD to be within osteoporosis range to reimburse bisphosphonate treatment, patients with improved BMD above this range after DMab treatment must continue bisphosphonate usage with high personal expenses. This acts as a drawback to implement standard-of-care [31]. Our observation suggests that proper actions are needed to improve patients’ education along with political approach to reshape reimbursement policy to support studies based on current evidence.

DMab discontinuation is associated with the substantial rapid increase of the risk of new and worsening vertebral fracture to the levels similar to the risk in untreated patients [6, 19, 32, 33]. Prior vertebral fracture, longer off-treatment duration, younger age, long-term use of DMab, lower hip BMD during and after DMab treatment, and concomitant use of bone-affecting drugs including aromatase inhibitors or glucocorticoids were reported as risk factors that increase the risk of rebound-associated fractures in previous literature [19, 29, 34]. Of note, there was a case report that showed spontaneous clinical vertebral fracture 12 months after discontinuation of 5 years of DMab treatment along with aromatase inhibitors in a 60-year-old woman with breast cancer despite the use of raloxifene initiated from 7 months after last DMab injection [35]. In this study, no incident morphometric or clinical vertebral fracture was observed during the follow-up period in both DD and DR groups. Given the reported predisposing factors for fracture associated with DMab discontinuation, this finding might be at least partly attributed to several factors including relatively short-term DMab use (median 2 doses), relatively higher hip BMD at the time of DMab discontinuation (average total hip T-score − 1.6 and − 1.7 in DR and DD group, respectively) and no concomitant use of aromatase inhibitors or glucocorticoids in this study population. However, it should be noted that this study lacks statistical power to compare fracture incidence between DD and DR groups considering the small sample size and short-term follow-up duration, with limited generalizability. In addition, although we did not detect any clinical vertebral fracture during follow-up in all study patients during follow-up after last DMab injection, morphometric assessment using spine X-ray or DXA vertebral fracture assessment were limited to 40 of 66 study subjects (60.6%), indicating the potential under-detection of morphometric vertebral fracture in the rest of study population (40%) who did not undergo any spine imaging during follow-up. We also observed one radius fracture in DD group that occurred 7 months after DMab discontinuation, in line with a prior study based on large healthcare claim database that showed increased nonvertebral fracture risk after DMab discontinuation compared to persistent users [33]. Taken together, it should be emphasized that in terms of prevention of rebound-associated fracture, strong antiresorptives such as bisphosphonates need to be implemented as the standard care after DMab discontinuation according to current clinical practice guidelines, particularly in patients with predisposing factors for rebound-associated fractures [19]. Although this study showed partial attenuation of bone loss at lumbar spine in raloxifene users compared to non-treatment after DMab discontinuation in relatively short-term DMab users in terms of BMD, this study may not be adequately powered to provide relevant information regarding fracture risk; this needs further validation in studies with larger sample size and adequate follow-up duration.

Our study has several limitations. Due to retrospective observational study design, residual bias cannot be excluded, although we tried to control potential confounders by PSM and by statistical adjustment in regression models. Because DMab became available in late 2016 in South Korea, our analysis was limited to patients who received DMab treatment less than 2 years. Use of raloxifene after DMab discontinuation in long-term DMab users need to be investigated in future. Since bisphosphonates were used as sequential treatment in the most patients in real-world setting following standard-of-care practice, relatively small number of DR and DD groups were inevitable; however, 33 subjects in each group in matched cohort yielded 73% statistical power at α of 0.05 to detect observed differences in BMD changes in lumbar spine between two groups in post hoc analysis. Further studies with larger sample size would be needed to validate our findings. Bone turnover markers were available in a subset of entire cohort, which may be insufficient to detect any differences in changes of bone markers between two groups. Although we decided to use propensity score matching to create a valid quasi-experimental comparison between DR and DD groups mainly due to imbalance in baseline BMD observed in unmatched cohort, propensity matching may lead to residual confounding in case of inexact matching [36, 37]. However, we observed that standardized bias reduced to prespecified imbalance threshold (< 0.2) after matching. Generalizability of study findings can be limited to those who excluded from the study during the matching process, which needs to be addressed in a larger, prospective cohort setting.

In conclusion, raloxifene treatment after short-term DMab use attenuated the BMD loss in lumbar spine after DMab discontinuation in postmenopausal women. These findings suggest that raloxifene treatment can be useful as an alternative to sequential therapy to partially preserve bone gain after DMab discontinuation. This result may be clinically useful when sequential treatment to bisphosphonate or DMab continuation is not applicable due to various reasons in postmenopausal women, which merits further investigation.

References

Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, Delmas P, Zoog HB, Austin M, Wang A, Kutilek S, Adami S, Zanchetta J, Libanati C, Siddhanti S, Christiansen C, FREEDOM Trial (2009) Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 361:756–765

Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, Brown JP, Chapurlat R, Cummings SR, Czerwinski E, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Kendler DL, Lippuner K, Reginster JY, Roux C, Malouf J, Bradley MN, Daizadeh NS, Wang A, Dakin P, Pannacciulli N, Dempster DW, Papapoulos S (2017) 10 Years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 5:513–523

Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D (2019) Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104:1595–1622

Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, Diab DL, Eldeiry LS, Farooki A, Harris ST, Hurley DL, Kelly J, Lewiecki EM, Pessah-Pollack R, McClung M, Wimalawansa SJ, Watts NB (2020) American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis—2020 update. Endocr Pract 26:1–46

Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, Kendler DL, Miller PD, Yang YC, Grazette L, San Martin J, Gallagher JC (2011) Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:972–980

Cummings SR, Ferrari S, Eastell R, Gilchrist N, Jensen JB, McClung M, Roux C, Törring O, Valter I, Wang AT, Brown JP (2018) Vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab: a post hoc analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled FREEDOM Trial and its extension. J Bone Miner Res 33:190–198

Grassi G, Chiodini I, Palmieri S, Cairoli E, Arosio M, Eller-Vainicher C (2021) Bisphosphonates after denosumab withdrawal reduce the vertebral fractures incidence. Eur J Endocrinol 185:387–396

Sølling AS, Harsløf T, Langdahl B (2021) Treatment with zoledronate subsequent to denosumab in osteoporosis: a 2-year randomized study. J Bone Miner Res 36:1245–1254

Anastasilakis AD, Papapoulos SE, Polyzos SA, Appelman-Dijkstra NM, Makras P (2019) Zoledronate for the prevention of bone loss in women discontinuing denosumab treatment. A prospective 2-year clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res 34:2220–2228

Kadaru T, Shibli-Rahhal A (2021) Zoledronic acid after treatment with denosumab is associated with bone loss within 1 year. J Bone Metab 28:51–58

Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, Knickerbocker RK, Nickelsen T, Genant HK, Christiansen C, Delmas PD, Zanchetta JR, Stakkestad J, Glüer CC, Krueger K, Cohen FJ, Eckert S, Ensrud KE, Avioli LV, Lips P, Cummings SR (1999) Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. JAMA 282:637–645

Michalská D, Stepan JJ, Basson BR, Pavo I (2006) The effect of raloxifene after discontinuation of long-term alendronate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:870–877

Ebina K, Hashimoto J, Kashii M, Hirao M, Miyama A, Nakaya H, Tsuji S, Takahi K, Tsuboi H, Okamura G, Etani Y, Takami K, Yoshikawa H (2021) Effects of follow-on therapy after denosumab discontinuation in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Mod Rheumatol 31:485–492

Hanson J (1997) Standardization of femur BMD. J Bone Miner Res 12:1316–1317

Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC (1993) Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 8:1137–1148

Miller PD, Bolognese MA, Lewiecki EM, McClung MR, Ding B, Austin M, Liu Y, San Martin J (2008) Effect of denosumab on bone density and turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass after long-term continued, discontinued, and restarting of therapy: a randomized blinded phase 2 clinical trial. Bone 43:222–229

Kendler D, Chines A, Clark P, Ebeling PR, McClung M, Rhee Y, Huang S, Stad RK (2020) Bone mineral density after transitioning from denosumab to alendronate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105:e255-264

Everts-Graber J, Reichenbach S, Ziswiler HR, Studer U, Lehmann T (2020) A single infusion of zoledronate in postmenopausal women following denosumab discontinuation results in partial conservation of bone mass gains. J Bone Miner Res 35:1207–1215

Tsourdi E, Zillikens MC, Meier C, Body JJ, Gonzalez Rodriguez E, Anastasilakis AD, Abrahamsen B, McCloskey E, Hofbauer LC, Guañabens N, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Ralston SH, Eastell R, Pepe J, Palermo A, Langdahl B (2020) Fracture risk and management of discontinuation of denosumab therapy: a systematic review and position statement by ECTS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa756

Makras P, Appelman-Dijkstra NM, Papapoulos SE, van Wissen S, Winter EM, Polyzos SA, Yavropoulou MP, Anastasilakis AD (2021) The duration of denosumab treatment and the efficacy of zoledronate to preserve bone mineral density after its discontinuation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 106:e4155–e4162

Seeman E, Crans GG, Diez-Perez A, Pinette KV, Delmas PD (2006) Anti-vertebral fracture efficacy of raloxifene: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 17:313–316

Barrionuevo P, Kapoor E, Asi N, Alahdab F, Mohammed K, Benkhadra K, Almasri J, Farah W, Sarigianni M, Muthusamy K, Al Nofal A, Haydour Q, Wang Z, Murad MH (2019) Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women: a network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104:1623–1630

Allen MR, Hogan HA, Hobbs WA, Koivuniemi AS, Koivuniemi MC, Burr DB (2007) Raloxifene enhances material-level mechanical properties of femoral cortical and trabecular bone. Endocrinology 148:3908–3913

Crandall CJ, Newberry SJ, Diamant A, Lim YW, Gellad WF, Booth MJ, Motala A, Shekelle PG (2014) Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments to prevent fractures: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 161:711–723

Chiu WY, Chien JY, Yang WS, Juang JM, Lee JJ, Tsai KS (2014) The risk of osteonecrosis of the jaws in Taiwanese osteoporotic patients treated with oral alendronate or raloxifene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:2729–2735

Lamy O, Stoll D, Aubry-Rozier B, Rodriguez EG (2019) Stopping denosumab. Curr Osteoporos Rep 17:8–15

Boquete-Castro A, Gómez-Moreno G, Calvo-Guirado JL, Aguilar-Salvatierra A, Delgado-Ruiz RA (2016) Denosumab and osteonecrosis of the jaw. A systematic analysis of events reported in clinical trials. Clin Oral Implants Res 27:367–375

Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, Adler RA, Brown TD, Cheung AM, Cosman F, Curtis JR, Dell R, Dempster DW, Ebeling PR, Einhorn TA, Genant HK, Geusens P, Klaushofer K, Lane JM, McKiernan F, McKinney R, Ng A, Nieves J, O’Keefe R, Papapoulos S, Howe TS, van der Meulen MC, Weinstein RS, Whyte MP (2014) Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: Second Report of a Task Force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 29:1–23

Burckhardt P, Faouzi M, Buclin T, Lamy O (2021) Fractures after denosumab discontinuation: a retrospective study of 797 cases. J Bone Miner Res 36:1717–1728

Swart KMA, van Vilsteren M, van Hout W, Draak E, van der Zwaard BC, van der Horst HE, Hugtenburg JG, Elders PJM (2018) Factors related to intentional non-initiation of bisphosphonate treatment in patients with a high fracture risk in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 19:141

Kim BK, Kim CH, Min YK (2021) Preventing rebound-associated fractures after discontinuation of denosumab therapy: a Position Statement from the Health Insurance Committee of the Korean Endocrine Society. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 36:909–911

McClung MR, Wagman RB, Miller PD, Wang A, Lewiecki EM (2017) Observations following discontinuation of long-term denosumab therapy. Osteoporos Int 28:1723–1732

Tripto-Shkolnik L, Fund N, Rouach V, Chodick G, Shalev V, Goldshtein I (2020) Fracture incidence after denosumab discontinuation: real-world data from a large healthcare provider. Bone 130:115150

Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A (2021) Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: a narrative review. J Clin Med 10:152

Gonzalez-Rodriguez E, Stoll D, Lamy O (2018) Raloxifene has no efficacy in reducing the high bone turnover and the risk of spontaneous vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation. Case Rep Rheumatol 2018:5432751

Austin PC (2009) Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 28:3083–3107

Sainani KL (2012) Propensity scores: uses and limitations. PM R 4:693–697

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the ‘SENTINEL (Severance ENdocrinology daTa scIeNcE pLatform)’ Program funded by the 2020 Research fund of Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea, and Sung-Kil Lim Research Award (4-2018-1215; DUCD000002) in statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Namki Hong, Sungjae Shin, Seunghyun Lee, Kyoung Jin Kim, and Yumie Rhee have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional and/or National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, with a waiver of written consent since the study design was based on retrospective medical record review (IRB No. 4-2021-1346).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, N., Shin, S., Lee, S. et al. Raloxifene Use After Denosumab Discontinuation Partially Attenuates Bone Loss in the Lumbar Spine in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 111, 47–55 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-022-00962-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-022-00962-4