Abstract

Rationale

Impulsivity has been strongly linked to addictive behaviors, but can be operationalized in a number of ways that vary considerably in overlap, suggesting multidimensionality.

Objective

This study tested the hypothesis that the latent structure among multiple measures of impulsivity would reflect the following three broad categories: impulsive choice, reflecting discounting of delayed rewards; impulsive action, reflecting ability to inhibit a prepotent motor response; and impulsive personality traits, reflecting self-reported attributions of self-regulatory capacity.

Methods

The study used a cross-sectional confirmatory factor analysis of multiple impulsivity assessments. Participants were 1252 young adults (62 % female) with low levels of addictive behavior, who were assessed in individual laboratory rooms at the University of Chicago and the University of Georgia. The battery comprised a Delay (replace hyphen with space) Discounting Task, Monetary Choice Questionnaire, Conners’ Continuous Performance Test, Go/NoGo Task, Stop Signal Task, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, and the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale.

Results

The hypothesized three-factor model provided the best fit to the data, although sensation seeking was excluded from the final model. The three latent factors were largely unrelated to each other and were variably associated with substance use.

Conclusions

These findings support the hypothesis that diverse measures of impulsivity can broadly be organized into three categories that are largely distinct from one another. These findings warrant investigation among individuals with clinical levels of addictive behavior and may be applied to understanding the underlying biological mechanisms of these categories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Individuals who have addictive disorders are often characterized as being “impulsive,” but impulsivity can be measured in a number of ways and is increasingly understood to be a multidimensional construct. One index is delay discounting (DD) (Ainslie 1975; Green and Myerson 2004; Bickel et al. 2014), a behavioral economic measure of preference for smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards and is also referred to as impulsive choice. A second form of impulsivity measures the capacity to inhibit a prepotent motor response, often referred to as impulsive action, and is assessed using measures such as the Go/NoGo and Stop Signal Tasks (Fillmore and Weafer 2013). A third form of impulsivity is as a personality trait, assessed using self-reported inventories, such as the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (Patton et al. 1995) and the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Whiteside and Lynam 2001; Cyders et al. 2007). These forms of impulsivity have each been consistently linked to addictive behavior (Stanford et al. 2009; MacKillop et al. 2011; Fillmore and Weafer 2013; Coskunpinar et al. 2013) but, in relation to each other, the associations vary considerably (Petry 2001; Cyders and Coskunpinar 2011; Murphy and MacKillop 2012; Courtney et al. 2012), ranging from moderate links to no association at all. These findings suggest that there is no single underlying construct of impulsivity but a number of different facets or dimensions. This, in turn, is problematic for a number of reasons. The use of a catch-all term impulsivity to refer to distinct characteristics may foster ambiguity and confusion in the literature. Furthermore, definitional ambiguities may undermine efforts to understand the biological basis of self-regulatory processes.

Given the evidence of multidimensionality, several studies have examined the relationships among measures of impulsivity to identify their underlying latent structure (Reynolds et al. 2006; Sharma et al. 2013; Sharma et al. 2014; MacKillop et al. 2014; Stahl et al. 2014; Caswell et al. 2015), revealing some meaningful patterns. However, the factor solutions have varied, potentially because the specific measures used vary across studies and the studies often also include other constructs such as reward sensitivity, risk taking, cognitive interference, or memory. In addition, few studies have included multiple indicators of more lengthy task-based assessments of impulsive choice and impulsive action, making it difficult to identify the underlying latent factors. An exception to this was a recent study disentangling interrelationships putatively involved in impulsive action, which found several elemental cognitive processes aggregated together and behavioral measures of impulsivity were not significantly related to self-reported measures of impulsivity (Stahl et al. 2014).

A broader issue that complicates the assessment of impulsivity is that the processes may recursively change over the course of addiction. On one hand, there is empirical support for impulsivity being a relatively stable trait that predicts the onset and progression of drug use (Doran and Trim 2013; Audrain-McGovern et al. 2009; Settles et al. 2010; Moffitt et al. 2011; Odum 2011; Quinn and Harden 2013; Fernie et al. 2013). On the other hand, there is also evidence that repeated use of drugs makes individuals more impulsive (Elkins et al. 2006; Simon et al. 2007; Mendez et al. 2010; Quinn et al. 2011; Quinn and Harden 2013), a change that apparently returns to normal after recovery (Yi et al. 2008; Bankston et al. 2009; Blonigen et al. 2013; Cicolini et al. 2014; Littlefield et al. 2015; Hulka et al. 2015). Thus, impulsivity can both predate and result from the drug use, serving as both a cause and consequence, and making it difficult to interpret cross-sectional studies of impulsivity in individuals with addictive disorders. A final complication is that measures of impulsivity also change across the life span (Green et al. 1999; Stanford et al. 2009), and many previous studies have used very broad age ranges, adding a further source of variability to the behaviors and their interrelationships.

To summarize, impulsivity is a multidimensional construct and latent aggregations among measures suggest a smaller number of underlying processes. The current study sought to test the hypothesis that the three broad domains of impulsivity described above—impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality traits—reflect meaningful and quantitatively discrete latent domains. Rather than a descriptive exploratory factor analytic approach, the study used a hypothesis-testing confirmatory factor analysis approach. To address a number of methodological issues noted above, the study included an array of widely used assessments reflecting the three domains and intentionally focused on the latent interrelationships in a sample with relatively low substance use to avoid influences of recent or persistent use. Finally, to avoid conceptual and quantitative imprecision, the study did not include assessments that measured related but nonetheless different constructs (e.g., reward sensitivity, risk taking).

Methods

Participants

Participants were enrolled at two sites, the University of Chicago and the University of Georgia. Eligibility criteria included verification of sobriety via breathalyzer (Alco-Sensor III or IV, Intoximeters, St. Louis, MO), no evidence of recent drug use via urine drug screen (ToxCup, Branan Medical Co., Irvine, CA, and iCup, Alere North America, LLC, Orlando, FL; amphetamine, cocaine, methamphetamine, opiates, and tetrahydrocannabinol), and scores of 11 or below on the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor et al. 2001) and Drug Use Disorder Identification Test (DUDIT) (Berman et al. 2005). The AUDIT and DUDIT criteria were not intended as stringent criteria for entirely excluding substance use but to screen out individuals with heavy levels of use or substance use disorders. Given the high normative prevalence of substance use among young adults (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014), excessively low AUDIT/DUDIT criteria were considered a threat to the external validity of the study. A criterion of 11 was selected to optimize specificity (i.e., to minimize inclusion of individuals with active substance use disorders) (Aertgeerts et al. 2000; Aertgeerts et al. 2001). In addition, participants were required to be between 18 and 30 years old. The sample comprised 1252 young adults (62 % female), described in Table 1 (sample characteristics by site are in Supplementary Table S1). In general, the sample can be characterized as individuals of European ancestry in their early 20s reporting low levels of alcohol and other drug use.

Assessments

Impulsive choice (discounting of delayed rewards)

Impulsive choice was assessed using four indices of monetary DD that were generated from two measures, a full iterative permuted Delay-Discounting Task (Amlung et al. 2013) and an abbreviated set of preconfigured items, the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ) (Kirby et al. 1999). The task used a 80-item task, comprising choices between smaller immediate rewards (i.e., $10.00, $20.00, $30.00, $40.00, $50.00, $60.00, $70.00, $80.00, $90.00, or $99.00) and a larger delayed reward ($100) with a delay of 1, 7, 14, 30, 60, 90, 180, or 365 days (Amlung et al. 2013). Discounted amounts and time delays were randomly admixed throughout the task. The MCQ consists of 27 randomized choices between smaller immediate rewards and larger delayed rewards (Kirby et al. 1999), with the latter ranging from $11 to $85 at varying intervals of delay from 1 week to 186 days. The items generate k values for three magnitude of reward: small (mean = $25), medium (mean = $55), and large (mean = $85) magnitude rewards. Hyperbolic temporal discounting functions (k) (Mazur 1987) were generated from both measures, although the iterative task used empirical derivation for each participant and the MCQ used inferred k values from preconfigured items relating to a finite set of values. Ten control items were included, assessing smaller versus larger rewards that were both immediately available. Invalid performance was defined as three or more erroneous selections on the delay-discounting control trials (i.e., larger amount versus smaller amount, both available immediately, selection of larger amount reflecting a valid response). To maximize validity, DD performance was incentivized for participants to potentially receive an outcome from their choices (Kirby et al. 1999).

Impulsive action (inhibition of a prepotent response)

Impulsive action was assessed using the following three behavioral tasks: a Go/NoGo Task (GNG), a Stop Signal Task (SST), and a Conner’s Continuous Performance Test (CPT); all of which measure capacity to inhibit a dominant arising response. Specifically, in the GNG (Kiehl et al. 2001), participants viewed two different kinds of visual stimuli and were instructed to either press a key in recognition or to withhold a response. The “Go” stimulus requiring an emitted response was an “X” (85 % of stimuli, 68 trials), and the NoGo stimulus requiring an inhibited response was a “K” (15 %, 12 trials). The primary index of response inhibition was errors of commission (i.e., providing a positive Go behavior in response to a NoGo stimulus). Second, the SST (Verbruggen and Logan 2008) also measured the ability of participants to inhibit prepotent responses but in a somewhat different way. Participants were instructed to press a keyboard button to make a shape discrimination as quickly as possible when a square or circle was presented. However, on a minority of trials, an auditory signal to inhibit their response (“Stop”) was presented just following shape presentation (i.e., 50–250 ms). In total, the task included 150 Go trials (requiring a button press corresponding to the square or circle presented) and 50 Stop trials (requiring interruption of the initiated response); the first eight trials were practice trials (six Go, two Stop). The primary index of response inhibition was percent inhibition errors. Third, the CPT (Beck et al. 1956) assessed capacity to inhibit prepotent responses by presenting visual stimuli to which the dominant response is to provide a motor response (button press), and in a minority of instances, a stimulus is presented to which no response should be provided. Specifically, participants were instructed to press the space bar when any alphabetic letter is presented (90 %; 324 trials), except for an X (10 %; 36 trials). The primary index of response inhibition was errors of commission. The measure is highly similar in format to the Go/NoGo Task but uses more varied Go stimuli and has a considerably larger number of trials.

Impulsive personality traits

The UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale is 59-item measure of impulsive personality traits (IPTs) (Whiteside and Lynam 2001; Cyders et al. 2007). The scale includes the following five subscales: (lack of) premeditation, a propensity to act without considering potential consequences (α = 0.85); negative urgency, a proclivity for acting on immediate cues when experiencing negative affect (α = 0.87); positive urgency, a proclivity for acting on immediate cues when experiencing positive affect (α = 0.93); (lack of) perseverance, an inability to follow through on tasks (α = 0.85); and sensation seeking, an orientation toward engaging in high energy and thrill behaviors (α = 0.86). The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) version 11 is a 30-item measure of IPTs (Patton et al. 1995). The responses were examined using the second-order factors (i.e., attentional, motor, and nonplanning). The attentional subscale reflects the ability to focus on the task at hand and the amount of thought insertions and racing thoughts one has (e.g., “I often have extraneous thoughts when thinking”; α = 0.70). The motor subscale reflects the tendency to act on the spur of the moment and consistency of lifestyle (e.g., “I do things without thinking”; α = 0.64). The nonplanning subscale reflects the ability to plan and think carefully and one’s enjoyment of challenging mental tasks (e.g., “I am a careful thinker”; α = 0.68).

Substance use

As noted above, the AUDIT and DUDIT were used as measures of alcohol and overall drug use. Smoker status was defined by self-reported frequency of smoking.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the general community at both sites and also from the Department of Psychology undergraduate human subject research pool at the University of Georgia site (n = 426; 34 % of the total sample). Participants were screened by telephone or over the internet to assess their eligibility, followed by in-person breath tests (subjects with BAC >0.00 were excluded) and urine drug screens (subjects with any positive results were excluded). During the assessment session, participants first underwent informed consent and then were administered the assessments via computer in individual private assessment rooms. The assessments were delivered via EPrime (PST Technology) or Inquisit software (Millisecond Inc.), and all measures were counterbalanced by participant to avoid order effects. Biological samples, not discussed here, were collected following the task-based and self-reported measures. After completion of the study, participants were debriefed and compensated for their time. Participants were either paid $40 or received research participation credits and also had a one in six chance of receiving an outcome from the delay discounting assessments (Kirby et al. 1999). All procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards.

Data analysis

Participant data were initially examined for missing values, misunderstanding of instructions, and adequate task attention/effort. For the DD assessments, a criterion of 80 % correct on the control items was used to define valid performance. For the behavioral inhibition tasks, invalid performance was defined ≤80 % accuracy on Go trials or ≥90 % inhibitory errors, putatively reflecting misunderstanding of the correct response keys or very low task effort. Temporal discounting functions were derived using nonlinear regression to fit Mazur’s hyperbolic discounting equation, v d = V/(1 + kd), where v d = discounted value of the future reward, V = value of the future reward, d = delay in days, and k is the derived temporal discounting function. This was implemented using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All manifest variables were examined for distributions and modified as necessary using transformations. Structural equation modeling was conducted via Mplus 7.11 software (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015). To evaluate a measurement model and the dimensionality of impulsivity, a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with continuous factor indicators were conducted (Brown 2015), estimating continuous latent varaibles and their factor structure. A maximum likelihood model estimator was used to evaluate model fit. The following recommended statistical fit criteria from Hu and Bentler (1999) were utilized to assess model fit: comparative fit index (CFI) >0.90, the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) <0.08, and the root-mean-square residual and standardized index (SRMR) <0.08. Lastly, despite the deliberately restricted range of the sample, path analyses in the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework were used to examine the associations of the factor solution with substance use variables.

Results

Preliminary analyses

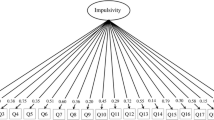

A small amount of data was missing or invalid due to failed data logging, premature task termination, or invalid performance (CPT = 0.006 %, GNG = 0.02 % and 0.008 %, DD tasks = 0.005 %). After testing missing data patterns, data met criteria for missing at random (Little and Rubin 2002); therefore, full information maximum likelihood approach was employed to handle missing data optimally. Average performance on the ten DD control items was very high (mean = 9.8; SD = 0.5). The hyperbolic temporal discounting function provided a very good fit to the DD task data (median R 2 = 0.86 [IQR = 0.66–0.93]). Consistency of preferences across the DD tasks was high (means = 97–98 %, SDs = 3–4 %). The DD k values were skewed and were logarithmically transformed, which substantially improved the distributions. Zero-order correlations among the measures are in Fig 1.

Bivariate correlation associations among the manifest indicators. Correlations of ≥|0.06| meet the traditional statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.05 and correlations of ≥|.10| the statistical threshold of p < 0.001. CPT Continuous Performance Task, GNG Go/NoGo Task, SST Stop Signal Task, DDT Delay-Discounting Task, MCQ Monetary Choice Questionnaire

Test of latent measurement models

Latent structural solutions were evaluated hierarchically within a CFA framework, standardizing all items to allow common scaling across measures (Table 2). First, a single latent factor of impulsivity was evaluated, using the four indicators of impulsive choice, three indicators of impulsive action, and eight indicators of IPTs, resulting in a poor model fit. In addition, multiple factor loadings were below the recommended criteria (λ > 0.4).

Second, a two-factor model was evaluated, separating IPTs from the behavioral tasks (combining impulsive choice and impulsive action indices together). The two-factor model showed a significant improvement in model fit compared to a unidimensional model (∆χ 2 (1) = 10.37). However, the overall model fit was still poor.

Third, the hypothesized three-factor model was evaluated (Fig. 2). The three-factor model showed a significant improvement in model fit compared to the two-factor model of impulsivity (∆χ 2 (2) = 4533.02), although suggested modifications to ascertain a stable and valid factor solution. Factor loading, factor covariance, and manifest variable estimates were examined, and the loading coefficient of sensation seeking was identified as low (λ < 0.2). A modified model, dropping sensation seeking, showed a significant improvement in the trait loading coefficients and the model fit. Finally, several modification indices (MIs) were >10, suggesting further modifications to improve the model. Model corrections were conducted hierarchically based on substantive and statistical criteria (Brown 2015). Specifically, MIs favored freeing error covariances between positive and negative urgencies on the UPPS and perseverance and motor on the BIS. This resulted in a significantly improved model fit (∆χ 2 (1) = 311.52) according to all indices, with statistically significant variable loadings and satisfactorily large standardized factor loadings (>0.4; Fig. 2), signifying that the latent variables were effectively measured by their indicators (Table 3). Last, tests of measurement invariance by sex were pursued (Meade and Lautenschlager 2004). Using criterion χ 2∆ < 0.05 or CFI∆ < 0.01 (Brown 2015), the results revealed support for configural, metric, and scalar measurement invariance (Supplementary Table S2).

Structural model of the three latent domains of impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality traits with the associated manifest indicators. Note that the delay discounting variables were base-10 logarithmically transformed and sensation seeking was initially considered as part of impulsive personality traits but was not included in the final model

Given that freeing residual error to covary could suggest the presence of another unspecified latent factor, an exploratory four-factor model was pursued to evaluate whether the BIS and UPPS subscales reflect distinct latent factors. Although the model fit was satisfactory for this model (Table 2), the BIS and UPPS latent factor covariance was 0.995, suggesting structual redundancy between the two and that the three-factor solution was more parsimonious.

Associations with substance use

An SEM model evaluated the associations between the latent factors and substance use behaviors as outcome variables. In addition, gender, income, age, education, and site were entered as covariates to control for their potential effect on paths tested in the structural model (Table 2). The results revealed that the AUDIT was significantly associated with impulsive choice and IPT factor, but not with not impulsive action, whereas the DUDIT was exclusively associated with the IPT factor. Using the same covariates, sensation seeking was significantly correlated with AUDIT (r = 0.15, p < 0.001), DUDIT (r = 0.15, p < 0.001), and smoking behavior (r = 0.08, p = 0.004; Table 4).

Discussion

This study tested the hypothesis that the construct of impulsivity could be empirically separated into three discrete domains using an array of standardized tasks and questionnaires in a large sample of young adults with relatively low levels of substance use. In general, the hypothesis was supported: three latent domains were identified, and these corresponded to impulsive choice, impulsive action, and IPTs. The three-factor model exhibited superior structural fit compared to the control models and revealed a robust internal factor structure. Loadings within each of the three domains were statistically significant and of moderate to very large magnitude, but the associations between domains were modest. Although there was a statistically significant relationship between IPTs and both impulsive choice and impulsive action, the effect sizes were small and there was a virtually nil relationship between impulsive choice and impulsive action. Notably, this latter dissociation is generally consistent with a recent meta-analysis of self-reported and task-based measures (Cyders and Coskunpinar 2011) and a recent SEM-based examination of elemental processes related to impulsive action (Stahl et al. 2014). More significantly, though, these findings provide further evidence that the notion of a singular psychological construct of impulsivity is not a valid one. Instead, the current data support the idea that the diverse tools for measuring impulsivity fall into three meaningful and relatively distinct categories and suggest a sound organizing framework for studying self-regulatory capacities. In doing so, these findings also provide empirical support for the terms of impulsive choice and impulsive action, which are increasingly used to describe delay discounting and behavioral inhibition, and suggest that using the singular term impulsivity is not a useful scientific practice. Although it may be desirable for expediency or heuristic value, the term’s implication that there is an overarching trait of impulsivity is simply not borne out empirically, here or in other recent work (Cyders and Coskunpinar 2011; MacKillop et al. 2014; Stahl et al. 2014).

An important caveat, however, is that the assessment modality varied substantially across the measures. Impulsive choice was measured via behavioral choices on decision-making tasks, impulsive action was measured via motor responses on inhibitory control tasks, and IPTs were ascertained via self-report on the BIS and the UPPS. These modality differences parallel the hypothesized three-factor structure, but extracting possible influences on the latent interrelationships is not possible. This is because the impulsivity constructs were in their standard assessment formats that are embedded within these modalities. The measures are the prism through which the underlying constructs are refracted and cannot be dissociated from them. As a result, some caution is warranted regarding the findings and the need for new tools that avoid the overlap between construct and modality is clear. However, there are also reasons to think assessment modality was not a major contributor. The study used two categories of behavioral tasks (impulsive choice and impulsive action), and the final model was superior to the control model that aggregated the two domains of behavioral tasks together. Nonetheless, the evidence for three separate factors would be more definitive if the ascertainment methods were identical or highly similar across measures.

Several notable additional findings emerged from the study. For example, one candidate index was not implicated in any of the three domains. The personality dimension of sensation seeking did not cohere within the IPT factor as predicted and did not exhibit meaningful associations with impulsive action or impulsive choice. Although sensation seeking is considered an impulsivity-related trait within the UPPS measure, these data suggest that the preference for exciting or highly stimulating experiences is quantitatively distinct from the other self-reported indices. This suggests that sensation seeking represents a trait that is independent of self-regulation, and this makes conceptual sense in the context of the other measures. For impulsive choice, an individual regulates the impulse to choose an immediate reward; for impulsive action, an individual regulates the impulse to emit the prepotent motor response; and for the other indicators of IPTs, an individual regulates various forms of more dominant preference (e.g., to act without deliberation, to give up on tasks). In contrast, sensation seeking refers to a certain set of predilections but not attempts to rein in those preferences. Also notable was the very high magnitude loadings of the impulsive choice indicators relative to the other indicators and their respective domains. This suggests that monetary delay-discounting preferences are very highly consistent across measures, even in the presence of differing delayed reward magnitudes.

The study design deliberately excluded heavy drug or alcohol users to minimize the possibility that individual differences were a result, rather than a possible cause, of drug use. Nonetheless, the associations between the latent indicators and alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use were examined for exploratory purposes. This revealed highly variable relationships, further attesting to the discriminant validity among the domains. Substance use of all three forms was significantly associated with IPTs, whereas only alcohol use (and smoking to an extent) was significantly associated with impulsive choice, and none of the three were associated with impulsive action. These relationships are tentative, given the narrow range of drug use, but provide some evidence that IPTs and impulsive choice are relevant even at low levels of substance involvement. With regard to associations with other variables, age was a robust predictor of impulsive action and education was robustly, inversely associated with impulsive choice and IPTs, but no significant associations were present with sex or income.

Part of the rationale for clarifying the interrelationships among impulsivity variables is to improve the measurement of these characteristics to clarify their biological foundations, especially genetic influences. Candidate gene studies have reported significant associations between a number of loci and measures of impulsive choice, impulsive action, and IPTs (Eisenberg et al. 2007; Benko et al. 2010; Filbey et al. 2012), and there is increasing evidence of substantial heritability for impulsive choice from twin studies and preclinical models (Anokhin et al. 2011; Crosbie et al. 2013; Richards et al. 2013; Anokhin et al. 2014). Given limited overlap, the current study suggests that genetic associations with a phenotype in one of the three domains might be predicted to extend to others within the domain but not to the other two.

The current findings should be interpreted in the context of a number of considerations. The study used a hypothesis-driven approach to characterize the latent structure of 13 impulsivity indicators but cannot speak to other related constructs or measures. For example, risk taking and reward sensitivity are often considered to be similar to self-regulatory processes, but the current study cannot address the extent to which measures from those domains may selectively cohere with the three domains characterized. This is a natural next step in this line of inquiry. Similarly, this study with low-severity participants cannot speak to the latent structure of impulsivity measures among clinically diagnosed individuals. A logical hypothesis is that the same tripartite structure would be present, but it is possible that active addiction could affect the domains in different ways and affect the latent structure. Methodologically, it was notable that the final model freed two error covariances, both on subscales within the two IPT questionnaires, which may be attributable to response styles on the respective measures, although that is necessarily conjecture. Finally, a generalizability consideration is that the sample was largely of European ancestry. Again, a logical hypothesis is that these processes will be consistent across races, but that cannot be addressed here. Fundamentally, these are empirical questions and priorities for future studies investigating the nature and categorizations of self-regulatory processes in drug addiction.

In sum, this study conducted a high-resolution analysis of the interrelationships among diverse measures of impulsivity, suggesting that no single overarching impulsivity trait was present but that there were three meaningful latent categories. The results set the stage for future investigations refining the nature of impulsive choice, impulsive action, and IPTs in at-risk and clinical samples; investigating the influences of genetic variation and environmental exposures; and contextualizing these processes in relation to other pertinent traits, such as risk tolerance or reward sensitivity.

References

Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Bande-Knops J, et al. (2000) The value of CAGE, CUGE, and AUDIT in screening for alcohol abuse and dependence among college freshmen. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:53–57

Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Ansoms S, Fevery J (2001) Screening properties of questionnaires and laboratory tests for the detection of alcohol abuse or dependence in a general practice population. Br J Gen Pract 51:206–217

Ainslie G (1975) Specious reward: a behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychol Bull 82:463–496

Amlung M, Sweet LH, Acker J, et al. (2013) Dissociable brain signatures of choice conflict and immediate reward preferences in alcohol use disorders. Addict Biol. doi:10.1111/adb.12017

Anokhin AP, Golosheykin S, Grant JD, Heath AC (2011) Heritability of delay discounting in adolescence: a longitudinal twin study. Behav Genet 41:175–183. doi:10.1007/s10519-010-9384-7

Anokhin AP, Grant JD, Mulligan RC, Heath AC (2014) The genetics of impulsivity: evidence for the heritability of delay discounting. Biol Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.10.022

Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Epstein LH, et al. (2009) Does delay discounting play an etiological role in smoking or is it a consequence of smoking? Drug Alcohol Depend 103:99–106. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019

Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001) AUDIT: the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary health care. World Health Organization, Geneva

Bankston SM, Carroll DD, Cron SG, et al. (2009) Substance abuser impulsivity decreases with a nine-month stay in a therapeutic community. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 35:417–420. doi:10.3109/00952990903410707

Beck LH, Bransome ED, Mirsky AF, et al. (1956) A continuous performance test of brain damage. J Consult Psychol 20:343–350

Benko A, Lazary J, Molnar E, et al. (2010) Significant association between the C(−1019)G functional polymorphism of the HTR1A gene and impulsivity. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 153B:592–599. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.31025

Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, Schlyter F (2005) Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur Addict Res 11:22–31. doi:10.1159/000081413

Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, et al. (2014) The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 10:641–677. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724

Blonigen DM, Timko C, Moos RH (2013) Alcoholics anonymous and reduced impulsivity: a novel mechanism of change. Subst Abus 34:4–12. doi:10.1080/08897077.2012.691448

Brown TA (2015) Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press, New York, NY, US

Caswell AJ, Bond R, Duka T, Morgan MJ (2015) Further evidence of the heterogeneous nature of impulsivity. Personal Individ Differ 76:68–74. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.059

Cicolini G, Simonetti V, Comparcini D, et al. (2014) Impulsivity in inpatient substance abusers: an exploratory study. J Clin Nurs 23:896–899. doi:10.1111/jocn.12373

Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA (2013) Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:1441–1450. doi:10.1111/acer.12131

Courtney KE, Arellano R, Barkley-Levenson E, et al. (2012) The relationship between measures of impulsivity and alcohol misuse: an integrative structural equation modeling approach. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36:923–931. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01635.x

Crosbie J, Arnold P, Paterson A, et al. (2013) Response inhibition and ADHD traits: correlates and heritability in a community sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41:497–507. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9693-9

Cyders MA, Coskunpinar A (2011) Measurement of constructs using self-report and behavioral lab tasks: is there overlap in nomothetic span and construct representation for impulsivity? Clin Psychol Rev 31:965–982. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.001

Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, et al. (2007) Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess 19:107–118

Doran N, Trim RS (2013) The prospective effects of impulsivity on alcohol and tobacco use in a college sample. J Psychoactive Drugs 45:379–385. doi:10.1080/02791072.2013.844380

Eisenberg DT, Mackillop J, Modi M, et al. (2007) Examining impulsivity as an endophenotype using a behavioral approach: a DRD2 TaqI a and DRD4 48-bp VNTR association study. Behav Brain Funct 3:–2. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-3-2

Elkins IJ, King SM, McGue M, Iacono WG (2006) Personality traits and the development of nicotine, alcohol, and illicit drug disorders: prospective links from adolescence to young adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol 115:26–39. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.26

Fernie G, Peeters M, Gullo MJ, et al. (2013) Multiple behavioural impulsivity tasks predict prospective alcohol involvement in adolescents. Addiction 108:1916–1923. doi:10.1111/add.12283

Filbey FM, Claus ED, Morgan M, et al. (2012) Dopaminergic genes modulate response inhibition in alcohol abusing adults. Addict Biol 17:1046–1056. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00328.x

Fillmore MT, Weafer J (2013) Behavioral inhibition and addiction. In: MacKillop J, de Wit H (eds) The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of addiction psychopharmacology. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, pp. 135–164

Green L, Myerson J (2004) A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychol Bull 130:769–792. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769

Green L, Myerson J, Ostaszewski P (1999) Discounting of delayed rewards across the life span: age differences in individual discounting functions. Behav Process 46:89–96. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(99)00021-2

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J 6:1–55

Hulka LM, Vonmoos M, Preller KH, et al. (2015) Changes in cocaine consumption are associated with fluctuations in self-reported impulsivity and gambling decision-making. Psychol Med 45:3097–3110. doi:10.1017/S0033291715001063

Kiehl KA, Laurens KR, Duty TL, et al. (2001) Neural sources involved in auditory target detection and novelty processing: an event-related fMRI study. Psychophysiology 38:133–142

Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK (1999) Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J Exp Psychol Gen 128:78–87. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.128.1.78

Little R, Rubin DB (2002) Statistical analysis with missing values. Wiley, New York, NY US

Littlefield AK, Stevens AK, Cunningham S, et al. (2015) Stability and change in multi-method measures of impulsivity across residential addictions treatment. Addict Behav 42:126–129. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.002

MacKillop J, Amlung M, Few L, et al. (2011) Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology 216:305–321. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0

Mackillop J, Miller JD, Fortune E, et al. (2014) Multidimensional examination of impulsivity in relation to disordered gambling. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 22:176–185. doi:10.1037/a0035874

Mazur JE (1987) An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons ML, Mazur JE, Nevin JA, Rachlin H (eds) Quantitative analysis of behavior. The effect of delay and of intervening events of reinforcement value, vol 5. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, pp 55–73

Meade AW, Lautenschlager GJ (2004) A comparison of item response theory and confirmatory factor analytic methodologies for establishing measurement equivalence/invariance. Organ Res Methods 7:361–388

Mendez IA, Simon NW, Hart N, et al. (2010) Self-administered cocaine causes long-lasting increases in impulsive choice in a delay discounting task. Behav Neurosci 124:470–477. doi:10.1037/a0020458

Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, et al. (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:2693–2698. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010076108

Murphy CM, MacKillop J (2012) Living in the here and now: interrelationships between impulsivity, mindfulness, and alcohol misuse. Psychopharmacology 219:527–536. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2573-0

Muthén, L.K. and Muthén, B.O. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén

Odum AL (2011) Delay discounting: I’m a k, you’re a k. J Exp Anal Behav 96:427–439. doi:10.1901/jeab.2011.96-423

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES (1995) Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol 51:768–774

Petry NM (2001) Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology 154:243–250. doi:10.1007/s002130000638

Quinn PD, Harden KP (2013) Differential changes in impulsivity and sensation seeking and the escalation of substance use from adolescence to early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol 25:223–239. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000284

Quinn PD, Stappenbeck CA, Fromme K (2011) Collegiate heavy drinking prospectively predicts change in sensation seeking and impulsivity. J Abnorm Psychol 120:543–556. doi:10.1037/a0023159

Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H (2006) Dimensions of impulsive behavior: personality and behavioral measures. Personal Individ Differ 40:305–315. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.03.024

Richards JB, Lloyd DR, Kuehlewind B, et al. (2013) Strong genetic influences on measures of behavioral-regulation among inbred rat strains. Genes Brain Behav 12:490–502. doi:10.1111/gbb.12050

Settles RF, Cyders M, Smith GT (2010) Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychol Addict Behav 24:198–208. doi:10.1037/a0017631

Sharma L, Kohl K, Morgan TA, Clark LA (2013) “Impulsivity”: relations between self-report and behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 104:559–575. doi:10.1037/a0031181

Sharma L, Markon KE, Clark LA (2014) Toward a theory of distinct types of “impulsive” behaviors: a meta-analysis of self-report and behavioral measures. Psychol Bull 140:374–408. doi:10.1037/a0034418

Simon NW, Mendez IA, Setlow B (2007) Cocaine exposure causes long-term increases in impulsive choice. Behav Neurosci 121:543–549. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.121.3.543

Stahl C, Voss A, Schmitz F, et al. (2014) Behavioral components of impulsivity. J Exp Psychol Gen 143:850–886. doi:10.1037/a0033981

Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM, et al. (2009) Fifty years of the Barratt impulsiveness scale: an update and review. Personal Individ Differ 47:385–395

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville, MD

Verbruggen F, Logan GD (2008) Response inhibition in the stop-signal paradigm. Trends Cogn Sci 12:418–424. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.005

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR (2001) The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personal Individ Differ 30:669–689. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7

Yi R, Johnson MW, Giordano LA, et al. (2008) The effects of reduced cigarette smoking on discounting future rewards: an initial evaluation. Psychol Rec 58:163–174

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding sources

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DA032015 (de Wit, Palmer, MacKillop) and the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research (MacKillop).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacKillop, J., Weafer, J., C. Gray, J. et al. The latent structure of impulsivity: impulsive choice, impulsive action, and impulsive personality traits. Psychopharmacology 233, 3361–3370 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-016-4372-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-016-4372-0