Abstract

Rational

It has been suggested that phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors such as sildenafil may be effective in the treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Objective

This study was designed to investigate the effect of sildenafil added to risperidone as augmentation therapy in patients with chronic schizophrenia and prominent negative symptoms in a double-blind and randomized clinical trial.

Methods

Eligible participants in the study were 40 patients with chronic schizophrenia with ages ranging from 18 to 45 years. All patients were inpatients and were in the active phase of the illness and met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia. Patients were allocated in a random fashion: 20 to risperidone (6 mg/day) plus sildenafil (75 mg/day) and 20 to risperidone (6 mg/day) plus placebo. The principal measure of outcome was Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Results

Although both protocols significantly decreased the score of the positive, negative, and general psychopathological symptoms over the trial period, the combination of risperidone and sildenafil showed a significant superiority over risperidone alone in decreasing negative symptoms and PANSS total scores over the 8-week trial (between-subjects factor; F = 4.77, df = 1; P = 0.03; F = 5.91, df = 1, P = 0.02 respectively).

Conclusion

Therapy with 75 mg/day of sildenafil was well tolerated, and no clinically important side effects were observed. The present study indicates sildenafil as a potential adjunctive treatment strategy for treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. This trial is registered with the Iranian Clinical Trials Registry (IRCT1138901151556N11).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a debilitating illness, rating as one of the leading causes of lost years of quality of life since it affects general health, functioning, autonomy, subjective well being, and life satisfaction of those who suffer from it (Ueoka et al. 2010). The illness imposes a disproportionate burden on patients, their families, the healthcare systems, and the society (Mohammadi and Akhondzadeh 2001; Akhondzadeh 2006). Research suggests that the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, including problems with motivation, social withdrawal, diminished affective responsiveness, speech, and movement, contribute more to poor functional outcomes and quality of life for individuals with schizophrenia than the positive symptoms such as hallucination and delusion (Akhondzadeh 2001; Erhart et al. 2006; Buckley and Stahl 2007; Buchanan 2007). Treatment can also be difficult because none of the available antipsychotic medications have been consistently and reliably effective in controlling negative symptoms (Möller 2004; Murphy et al. 2006).

Theories bridging the dopamine and the NMDA hypotheses of schizophrenia into one conceptual framework argue that dopamine activity is under the control of NMDA inhibitory receptors (Akhondzadeh 1998; Noorbala et al. 1999; Laruelle et al. 2003; Carlsson et al. 2004; Coyle 2006). In schizophrenia, NMDA receptor hypofunction results in over activity of the dopaminergic system, leading to the suggestion that enhancing NMDA function may serve as an augmentation strategy or even possibly as a stand-alone therapy (Stahl 2007; Seeman 2009). Evidence that these agents have a primary effect on negative and cognitive symptoms is open to question and may be more closely related to improved side effect profiles Stahl 2007. Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors act to increase cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) without directly affecting NMDA receptors (Siuciak 2008; Reneerkens et al. 2009; Zhang 2010). Targeting PDE5 to increase cGMP might selectively correct deficits resulting from NMDA receptor hypofunction without the development of tachyphylaxis (Siuciak 2008; Reneerkens et al. 2009; Zhang 2010). Three PDE5 inhibitors are currently approved by FDA for the treatment of erectile dysfunction (sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil) (Gopalakrishnan et al. 2006). Sildenafil readily cross the blood–brain barrier, is relatively well tolerated, and recently have been found to have cognitive-enhancing and neuroprotective effects in rodents (Siuciak 2008; Reneerkens et al. 2009; Zhang 2010). Goff et al. treated 17 adult schizophrenia outpatients with a stable dose of antipsychotic (five subjects were treated with olanzapine, two with clozapine, two with aripiprazole, two with conventional antipsychotics, two with risperidone, one with quetiapine, and three with combination of antipsychotics) and a single oral dose of placebo, 50 mg sildenafil, or 100 mg sildenafil in random order with a 48-h interval between administrations (Goff et al. 2009). Despite evidence for cognitive-enhancing effects of sildenafil in animal models, the strategy for treating putative NMDA receptor-mediated memory deficits (short and long term) in schizophrenia with sildenafil 50 or 100 mg was not successful. Sildenafil did improve neither cognition nor symptoms of schizophrenia in that trial. Sildenafil was safe and effective when administered to male patients with schizophrenia for erectile dysfunction in two studies (Gopalakrishnan et al. 2006). Moreover, it has been suggested that PDE5 inhibitors may be effective in the treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Reneerkens et al. 2009; Zhang 2010). This study was designed to investigate the effect of sildenafil added to risperidone as augmentation therapy in patients with chronic schizophrenia and prominent negative symptoms in a double-blind and randomized clinical trial.

Methods

Trial setting

The trial was a prospective, 8-week, double-blind study of parallel groups of patients with chronic schizophrenia and was undertaken in three psychiatric hospitals in Iran, from December 2008 to May of 2010.

Participants

Eligible participants in the study were 40 patients with chronic schizophrenia (four women and 36 men) with ages ranging from 18 to 45 years (Table 1). All participants were inpatients, in the active phase of illness, and met DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000) criteria for schizophrenia. Minimum score of 60 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al. 1987) (range, 84–127) and ≥20 on the negative subscale (range, 20–35) was required for entry into the study. The patients did not receive neuroleptics for a week prior to entering the trial or long acting antipsychotics at least 2 months before the study. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a clinically significant organic and neurological disorder, serious psychotic disorders other than schizophrenia, use of any medications identified as contraindicated with sildenafil, treatment with antidepressant medication within 1 month of screening, and a current diagnosis of major mood or substance abuse disorder. The PANSS depression item score (exclusion level ≥4) was used to exclude patients with significant level of depression. Pregnant or lactating women and those of reproductive age without adequate contraception were also excluded. The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent revisions and approved by the ethics committee at Tehran University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 6551). Written informed consents were obtained before entering into the study.

Intervention

Twenty patients were randomly allocated to risperidone (6 mg/day) plus sildenafil (75 mg/day), and 20 patients were allocated to risperidone (6 mg/day) plus placebo for an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Starting dosage of risperidone was 2 mg/day and was increased in 2 mg increments daily to 6 mg/day. Patients were started on sildenafil 25 mg/day, and the dosage was increased to 75 mg/day at the end of the first week. The dose of sildenafil was selected based on a mean dose in the study of Goff et al. (2009). The patients in the placebo group received three identical tablets. The patients had a 1-week antipsychotic washout period before entering the study. During the washout period, the patients received benzodiazepine if necessary, and lorazepam was the drug of choice. Three patients dropped out of the study (one patient from the sildenafil group and two patients from the placebo group). Patients also received biperiden if they faced extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients were assessed by a psychiatrist at baseline and after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks after the start of medication.

Outcome

The principal measure of outcome was the PANSS that has been used in several studies in Iran (Akhondzadeh et al. 1999, 2006, 2007). PANSS total score was considered as primary efficacy and secondary efficacy parameters included the PANSS subscales. The PANSS includes 30 items on three subscales, seven items covering positive symptoms, seven items covering negative symptoms, and 16 covering general psychopathology. In addition, a total score presents all three parts (Kay et al. 1987). The raters used standardized instructions in the use of PANSS. The mean decrease in the PANSS score from baseline was used as the main outcome measure of patient response to treatment. Treatment response was defined as at least 50% improvement in the PANSS total score (Abbasi et al. 2010). Inter-rater reliability for the PANSS was greater than 0.80. The extrapyramidal symptoms were assessed using the Extrapyramidal Symptoms Rating Scale (ESRS) (part one: Parkinsonism, dystonia, dyskinesia—sum of 11 items) (Chouinard et al. 1980). Side effects were systematically recorded throughout the study and were assessed using a checklist administered by a psychiatrist on days 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56 (Table 3). The side effect checklist was a 25-item somatic complaint questionnaire. The checklist included a range of somatic complaints: nausea, headache, drowsiness, dizziness, tremor, change in weight, etc. Patients were randomized to receive sildenafil or placebo in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated code, and the randomization was stratified by on site. The assignments were kept in sealed opaque envelopes until data analysis. Throughout the study, the person who administered the medications, the rater, and the patients were blind to assignments.

Statistical analysis

A two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (time–treatment interaction) was used. The two groups as a between-subjects factor (group) and the five measurements during treatment as the within-subjects factor (time) were considered. This was done for positive, negative, and general psychopathology subscale, and PANSS total scores. A Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used for sphericity. To compare the two groups at baseline and at outcome of two groups at the end of the trial, an unpaired Student’s t test with a two-sided P value was used. To compare the demographic data and the frequency of side effects between the protocols, Fisher’s exact test was performed. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Differences were considered significant with P < 0.05. To consider α = 0.05 and β = 0.2, the final difference between the two groups was calculated to be at least a score of 5 on the Negative subscale of PANSS rating scale, S = 5 and power = 0.8 (based on a pilot study for this project). The sample size was calculated to be at least 15 in each group. Intention to treat (ITT) analysis with last observation carried forward procedure (that is a conservative approach for ITT) was performed. Data were analyzed by using commercially available statistical packages (SPSS 13.00. Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient disposition and characteristics

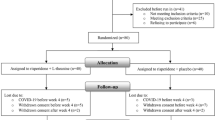

Sixty-two patients were screened for the study, and 40 were randomized to groups for trial medication (20 patients in each group) (Fig. 1). Twelve patients from Kuidistan University of Medical Sciences, 12 patients from Arak University of Medical Sciences, and 16 patients from Roozbeh psychiatric hospital were recruited to this study. No significant difference was identified between patients randomly assigned to the group 1 or 2 condition with regard to basic demographic data including age, age of first onset of illness, gender, marital status, level of education, and mean duration of illness (Table 1). During the washout period, five patients from the sildenafil group and seven patients from the placebo group received lorazapam.

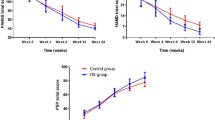

PANSS total scores

The mean ± SD scores of the two groups of patients are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups at week 0 (baseline) on the PANSS (t = 0.16, df = 38, P = 0.86). The difference between the two treatments was significant as indicated by the effect of group, the between-subjects factor (F = 5.91, df = 1, P = 0.02). The behavior of the two treatment groups was not similar across time (groups-by-time interaction, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected: F = 10.18, df = 1.74, P = 0.001). The difference between the two treatments was significant at the endpoint (week 8) (t = 4.22, df = 38, P < 0.001). The changes at endpoint compared with baseline were −59.15 ± 12.79 (mean ± SD) and −42.90 ± 12.90 for sildenafil and placebo, respectively. A significant difference was observed on PANSS total score at week 8 compared with baseline in the two groups (t = 3.95, df = 38, P < 0.001). In the sildenafil group 60% and in the placebo group 25% of the patients responded to treatment (at least 50% reductions in the PANSS total score).

Positive symptoms

The mean ± SD scores of two groups of patients are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups at week 0 (baseline) on the PANSS (t = 0.16, df = 38, P = 0.86). The difference between the two treatments was not significant as indicated by the effect of group, the between-subjects factor (F = 0.42, df = 1, P = 0.51). The behavior of the two treatment groups was similar across time (groups-by-time interaction, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected: F = 0.99, df = 1.79; P = 0.36). The difference between the two treatments was not significant at the endpoint (week 8) (t = 1.32, df = 38, P = 0.19).

Negative symptoms

The mean ± SD scores of two groups of patients are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups at week 0 (baseline) on the PANSS (t = 0.44, df = 38, P = 0.66). The difference between the two treatments was significant as indicated by the effect of group, the between-subjects factor (F = 4.77, df = 1; P = 0.03). The behavior of the two treatment groups was not similar across time (groups-by-time interaction, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected: F = 9.80, df = 1.50, P < 0.001). The difference between the two treatments was significant at the endpoint (week 8) (t = 4.17, df = 38, P < 0.001). The changes at the endpoint compared with baseline were −12.20 ± 3.44 (mean ± SD) and −6.26 ± 4.41 for sildenafil and placebo, respectively. A significant difference was observed on the negative subscale of PANSS at week 8 compared with baseline in the two groups (t = 4.77, df = 38, P < 0.001).

General psychopathological symptoms

The mean ± SD scores of two groups of patients are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the two groups at week 0 (baseline) on the PANSS (t = 0.28, df = 38, P = 0.77). The difference between the two treatments was not significant as indicated by the effect of group, the between-subjects factor (F = 2.39, df = 1, P = 0.13). The behavior of the two treatment groups was not similar across time (groups-by-time interaction, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected: F = 6.63, df = 1.52, P = 0.001). The difference between the two treatments was significant at the endpoint (week 8) (t = 2.74, df = 38, P = 0.009). The changes at the endpoint compared with baseline were −28.21 ± 10.98 (mean ± SD) and −19.80 ± 8.16 for sildenafil and placebo, respectively. A significant difference was observed on the general psychopathology subscale of PANSS at week 8 compared with baseline in the two groups (t = 2.77, df = 38, P < 0.01).

Extrapyramidal symptoms rating scale

Over the trial, the mean ESRS scores for the placebo group were higher than the sildenafil group. Nevertheless, the difference between the two treatments was not significant as indicated by the effect of group, the between-subjects factor (F = 2.35, df = 1, P = 0.25). The behavior of the two treatment groups was similar across time (groups-by-time interaction, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected: F = 0.76; df = 2.32, P = 0.39). No significant difference was observed between the overall mean biperiden dosages (mg) in two groups (109.04 ± 99.36 and 115.89 ± 94.68 for sildenafil and placebo group, respectively; mean ± SD). Moreover, the difference between the two treatments in terms of number of biperiden treatment days was not significant (15.27 ± 14.34 and 19.43 ± 13.68 for sildenafil and placebo group respectively; mean ± SD).

Clinical complications and side effects

Ten types of side effects were observed over the trial. The difference between the sildenafil and placebo in the frequency of side effects was not significant (Table 3). One hundred percent of each group had at least one adverse event over the trial period.

Discussion

The results of this study document that both groups of schizophrenic patients demonstrate significant improvement on the PANSS total score and on all subscales during the 8 weeks of treatment with risperidone. In agreement with our hypothesis, the sildenafil group had significantly greater improvement in the negative symptoms as well as total score of PANSS over the 8-week trial. Clinical characteristics of the schizophrenic patients, such as sex, age, and duration of illness, did not differ between groups and cannot explain differences in the therapeutic outcome. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report regarding kinetic interactions between sildenafil and atypical antipsychotics, and this led us to assume that the therapeutic effect shown by sildenafil on symptoms of schizophrenia is likely to result from a pharmacodynamic mechanism. Sildenafil acts to increase cGMP without directly affecting NMDA receptors. Targeting PDE5 to increase cGMP might selectively correct deficits resulting from NMDA receptor hypofunction (Siuciak 2008; Reneerkens et al. 2009; Zhang 2010).

This is, to our knowledge, the first reported randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with relatively adequate statistical power to test the efficacy of sildenafil when used in conjunction with antipsychotic pharmacotherapy for the treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. So far, several studies have shown positive effects of selective PDE5-Is on memory performance in the object recognition task in adult rats (Reneerkens et al. 2009). PDE5-Is are believed to enhance memory and learning via facilitation of long-term potentiation mediated by the “glutamate-nitric oxide-cyclic GMP intracellular pathway” (Siuciak 2008; Reneerkens et al. 2009; Zhang 2010). Goff et al. treated 17 adult schizophrenia outpatients with a stable dose of antipsychotic and a single oral dose of placebo, 50 mg sildenafil, or 100 mg sildenafil in random order with a 48-h interval between administrations (Goff et al. 2009). However, sildenafil did not improve cognition or symptoms of schizophrenia when added to antipsychotics. They mentioned that repeated dosing may be necessary to achieve therapeutic effects with sildenafil (Goff et al. 2009). Our results show that adjunctive sildenafil was well tolerated with minimal side effects. There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in terms of the rate of adverse events. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, there is no report of significant kinetic interactions between risperidone and sildenafil. The limitation of the present study, including the short duration of study, was that only patients with chronic schizophrenia and a fixed dose of sildenafil were taken into consideration, and this indicates the need for further research. In conclusion, the present study provides evidence for sildenafil as a potential adjunctive treatment strategy for treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Nevertheless, results of larger controlled trials are needed before recommendation for a broad clinical application can be made.

References

Abbasi SH, Behpournia H, Ghoreshi A, Salehi B, Raznahan M, Rezazadeh SA, Rezaei F, Akhondzadeh S (2010) The effect of mirtazapine add on therapy to risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res 116:101–106

Akhondzadeh S (1998) The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia. J Clin Pharm Ther 23:243–246

Akhondzadeh S (2001) The 5-HT hypothesis of schizophrenia. IDrugs 4:295–300

Akhondzadeh S (2006) Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia: the past, present and future. Curr Drug Ther 1:1–7

Akhondzadeh S, Mohammadi MR, Amini-Nooshabadi H, Davari Ashtiani R (1999) Cyproheptadine in treatment of chronic schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Pharm Ther 24:49–42

Akhondzadeh S, Rezaei F, Larijani B, Nejatisafa AA, Kashani L, Abbasi SH (2006) Correlation between testosterone, gonadotropins and prolactin and severity of negative symptoms in male patients with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 84:405–410

Akhondzadeh S, Tabatabaee M, Amini H, Ahmadi Abhari SA, Abbasi SH, Behnam B (2007) Celecoxib as adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res 90:179–185

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth edition, text revision. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Buchanan RW (2007) Persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull 33:1013–1022

Buckley PF, Stahl SM (2007) Pharmacological treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia: therapeutic opportunity or cul-de-sac? Acta Psychiatr Scand 115:93–100

Carlsson ML, Carlsson A, Nilsson M (2004) Schizophrenia: from dopamine to glutamate and back. Curr Med Chem 11:267–277

Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annables L, Jones BD (1980) Extrapyramidal symptoms rating scale (abstract). Can J Neurol Sci 7:233

Coyle JT (2006) Glutamate and schizophrenia: beyond the dopamine hypothesis. Cell Mol Neurobiol 26:365–384

Erhart SM, Marder SR, Carpenter WT (2006) Treatment of schizophrenia negative symptoms: future prospects. Schizophr Bull 32:234–237

Goff DC, Cather C, Freudenreich O, Henderson DC, Evins AE, Culhane MA, Walsh JP (2009) A placebo-controlled study of sildenafil effects on cognition in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol 202:411–417

Gopalakrishnan R, Jacob KS, Kuruvilla A, Vasantharaj B, John JK (2006) Sildenafil in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced erectile dysfunction: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose, two-way crossover trial. Am J Psychiatry 163:494–499

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13:261–276

Laruelle M, Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A (2003) Glutamate, dopamine, and schizophrenia: from pathophysiology to treatment. Ann NY Acad Sci 1003:138–158

Mohammadi MR, Akhondzadeh S (2001) Schizophrenia: etiology and pharmacotherapy. IDrugs 4:1167–1172

Möller HJ (2004) Non-neuroleptic approaches to treating negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 254:108–116

Murphy BP, Chung YC, Park TW, McGorry PD (2006) Pharmacological treatment of primary negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res 88:5–25

Noorbala AA, Akhondzadeh S, Davari-Ashtiani R, Amini-Nooshabadi H (1999) Piracetam in the treatment of schizophrenia: implications for the glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia. J Clin Pharm Ther 24:369–374

Reneerkens OA, Rutten K, Steinbusch HW, Blokland A, Prickaerts J (2009) Selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors: a promising target for cognition enhancement. Psychopharmacol 202:419–443

Seeman P (2009) Glutamate and dopamine components in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci 34:143–149

Siuciak JA (2008) The role of phosphodiesterases in schizophrenia: therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs 22:983–993

Stahl SM (2007) Novel therapeutics for schizophrenia: targeting glycine modulation of NMDA glutamate receptors. CNS Spectr 12:423–427

Ueoka Y, Tomotake M, Tanaka T, Kaneda Y, Taniguchi K, Nakataki M, Numata S, Tayoshi S, Yamauchi K, Sumitani S, Ohmori T, Ueno SI, Ohmori T (2010) Quality of life and cognitive dysfunction in people with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (in press)

Zhang HT (2010) Phosphodiesterase targets for cognitive dysfunction and schizophrenia—a New York Academy of Sciences meeting. IDrugs 13:166–168

Acknowledgment

This study was Dr. Raofeh Ghayyoumi’s postgraduate thesis toward the Iranian Board of Psychiatry.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare no conflict of interest.

Role of funding source

This study was supported by a grant from Tehran University of Medical Sciences to Prof. Shahin Akhondzadeh (grant no. 6551).

Competing interest

None.

Ethics approval

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (grant no. 6651).

The trial group

Shahin Akhondzadeh was the principal investigator and provided statistical support. He was also the clinical neuropsychopharmacologist from December 2008 to May 2010. Raofeh Ghayyoumi was the resident psychiatrist and trialist from December 2008 to May 2010. Farzin Rezaei, Bahman Salehi, Azad Maroufi, and Mehrangiz Naderi were the clinical coordinators and psychiatrists from December 2008 to May 2010. Gholam-Reza Esfandiari and Fariba Ghebleh were the psychologists from December 2008 to May 2010. Amir-Hossein Modabbernia and Mina Tabrizi were the methodologists from December 2008 to May 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akhondzadeh, S., Ghayyoumi, R., Rezaei, F. et al. Sildenafil adjunctive therapy to risperidone in the treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology 213, 809–815 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2044-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2044-z