Abstract

Rationale

Neurodevelopmental deficits of parvalbumin-immunoreactive γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic interneurons in prefrontal cortex have been reported in schizophrenia. Glutamate influences the proliferation of this type of interneuron by an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor-mediated mechanism. The present study hypothesized that prenatal blockade of NMDA receptors would disrupt GABAergic neurodevelopment, resulting in differences in effects on behavioral responses to a noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, phencyclidine (PCP), and a dopamine releaser, methamphetamine (METH).

Methods

GABAergic neurons were immunohistochemically stained with parvalbumin antibody. Psychostimulant-induced hyperlocomotion was measured using an infrared sensor.

Results

Prenatal exposure (E15–E18) to the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 reduced the density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in rat medial prefrontal cortex on postnatal day 63 (P63) and enhanced PCP-induced hyperlocomotion but not the acute effects of METH on P63 or the development of behavioral sensitization. Prenatal exposure to MK-801 reduced the number of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons even on postnatal day 35 (P35) and did not enhance PCP-induced hyperlocomotion, the acute effects of METH on P35, or the development of behavioral sensitization to METH.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that prenatal blockade of NMDA receptors disrupts GABAergic neurodevelopment in medial prefrontal cortex, and that this disruption of GABAergic development may be related to the enhancement of the locomotion-inducing effect of PCP in postpubertal but not juvenile offspring. GABAergic deficit is unrelated to the effects of METH. This GABAergic neurodevelopmental disruption and the enhanced PCP-induced hyperlocomotion in adult offspring prenatally exposed to MK-801 may prove useful as a new model of the neurodevelopmental process of pathogenesis of treatment-resistant schizophrenia via an NMDA-receptor-mediated hypoglutamatergic mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neurodevelopmental abnormality has been considered one of the pathogeneses of schizophrenia. Magnetic resonance imaging studies have revealed a reduction in the volume of not only the prefrontal cortex (Szeszko et al. 1999) but also the temporal lobe (Bogerts et al. 1990) even in first-episode schizophrenia. These structural changes are unassociated with gliosis (Roberts 1991). Furthermore, histological analysis has revealed an abnormality in the arrangement of neurons in the prefrontal cortex in patients with schizophrenia (Benes and Bird 1987).

Postmortem analysis of brain tissue has revealed loss of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic interneurons in the superficial layers of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia (Benes et al. 1991). Furthermore, GABAA receptor binding is increased in prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia; this increase is believed to reflect compensatory regulation of postsynaptic receptors to loss of GABAergic interneurons (Benes et al. 1996).

Nonoverlapping subpopulations of GABAergic neurons are defined by the presence of the calcium-binding proteins parvalbumin, calbindin, and calretinin (Demeulemeester et al. 1988; Celio 1990). Parvalbumin is a Ca2+-binding protein that is found in fast-firing GABAergic interneurons, where it influences the activity of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels and Ca 2+ influx (Plogmann and Celio 1993; McPhalen et al. 1994). The density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons is reduced in prefrontal cortex (Brodmann areas 9 and 10) in schizophrenia (Beasley and Reynolds 1997; Beasley et al. 2002; Lewis et al. 2005). Although these findings do not necessarily mean that these GABA-related deficits are neurodevelopmental in nature, neurodevelopmental deficits might exist in specific populations of GABAergic interneurons in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia.

Valproic acid, which enhances GABAergic neurotransmission (Loscher 1999; Vriend and Alexiuk 1996) when coadministered with olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol, is more effective in pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia than monotherapy with the atypical antipsychotics (Wassef et al. 2000; Casey et al. 2003). Furthermore, lamotrigine, which can stimulate GABAergic inhibitory transmission (Leach et al. 1986; Cunningham and Jones 2000), is effective against treatment-resistant schizophrenia when combined with clozapine (Dursun and Deakin 2001; Tiihonen et al. 2003). These findings suggest that neurodevelopmental GABAergic dysfunction is related to some types of pathophysiology in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Prenatal exposure to the noncompetitive N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist MK-801 induces long-lasting decreases in parvalbumin-positive GABAergic neurons in the rat striatum (Sadikot et al. 1998). Additionally, prenatal exposure to ethanol, which not only stimulates GABAA receptors but also blocks NMDA receptors (Ikonomidou et al. 2000), leads to long-lasting deficits of GABAergic interneurons in rat prefrontal cortex and increased spontaneous locomotor activity in adult offspring (Moore et al. 1998; Bailey et al. 2001). Glutamate plays, via NMDA receptors, an important role in the migration of immature neurons (Komuro and Rakic 1993; Behar et al. 1999; Csillik et al. 2002).

Induction of hyperlocomotion by NMDA receptor antagonists, such as phencyclidine (PCP) and dizocilpine (MK-801), is a model of the NMDA-receptor-mediated hypoglutamatergic pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Javitt and Zukin 1991), as clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic which enhances NMDA-mediated glutamatergic neurotransmission (Millan 2005), is effective in blocking this abnormal behavior (Corbett et al. 1995; Gleason and Shannon 1997; Abekawa et al. 2003), while haloperidol, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, only weakly blocks PCP-induced abnormal behavior. NMDA receptor-mediated hypoglutamatergic transmission has thus been postulated to play a role in the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist-resistant pathophysiology of schizophrenia. On the other hand, repeated administration of amphetamine (AMPH)/methamphetamine (METH), which has the principal effect of increasing dopamine levels in dopaminergic terminals, results in behavioral sensitization to its own locomotion-inducing effect (Kalivas et al. 1993). AMPH/METH-induced hyperlocomotion is considered a model of the dopamine D2-receptor-mediated hyperdopaminergic pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Sato et al. 1983), as this behavioral sensitization is related to enhanced dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens (Robinson and Becker 1986; Pierce and Kalivas 1997).

The present study hypothesized that prenatal blockade of NMDA receptors in the fetal brain would induce long-lasting GABAergic deficits, and that these deficits in GABAergic development would result in differences in effects of a noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, PCP-induced hyperlocomotion from a dopamine releaser, METH-induced abnormal behavior. To test this hypothesis, we administered the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 prenatally from E15 to E18, the most important period for neuronal proliferation (Sadikot et al. 1998), and then examined not only the density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive GABAergic interneurons in rat medial prefrontal cortex on P35 (juvenile) and P63 (postpubertal) but also PCP-induced hyperlocomotion on P35 and P63, and the development of METH-induced behavioral sensitization from P35 and P63.

Materials and methods

Animals

This study was conducted in accord with a guide for the care and use of laboratory animals regulated by Hokkaido University School of Medicine and National Institute of Health guidelines on animal care. Sprague−Dawley (SD) dams were impregnated while at Sankyo Labo Service Corporation (Japan). SD female rats were placed individually with a male rat overnight until vaginal smear the following morning was indicative of insemination. This was defined as gestational day 0 (E0). The dams (E7) were obtained from the Sankyo Labo Service Corporation. The dams were divided into two groups. MK-801 group was injected with 0.2 mg/kg of MK-801 from E15 to E18. Saline control group was injected with 1 ml/kg of saline from E15 to E18. Food and water intake of all animals was monitored daily. MK-801 group was allowed free access to standard laboratory diet and tap water. Saline control groups were coupled 2 days later than MK-801 group to allow matching food and water consumption of dams at comparable gestational ages. At birth [postnatal day 0 (P0)], pups were culled to include eight animals per litter. The pups of different groups were fostered separately. On P21, the pups were weaned from their mothers. After weaning, the pups from different treatment group litters were mixed and housed by gender in groups of three or four until P28. From P29, the pups were housed individually.

Drugs

MK-801 (dizocilpine; 0.2 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich), PCP hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich; 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 mg/kg), and METH (Dainippon Seiyaku Pharmaceutical, Japan; 0.3, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/kg) each was dissolved in saline. MK-801 and PCP were injected intraperitoneally, and METH was injected subcutaneously at the volume of 1 ml/kg. The doses of PCP and METH refer to salt.

Immunohistochemical study

On P63 and P35, animals different from those for behavioral study were euthanized by pentobarbital overdose (0.5–0.8 ml) before transcardial perfusion with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M phosphate containing 0.9% sodium chloride; pH = 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (in the 0.1-M PBS). Brains were removed, postfixed overnight in the same fixative at 4°C, and stored in 30% sucrose solution at 4°C.

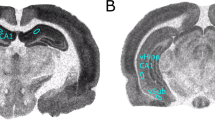

The serial coronal sections of the brains were cut (30 μm sections) through the medial prefrontal cortex [Fig. 8; The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates (Third Edition edited by Paxinos and Watson 1997)] on a freezing microtome, and sections were stored in 4°C 1 × PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide. Free-floating sections were immunostained for parvalbumin using a monoclonal antibody (CHEMICON). Free-floating sections were washed three times for 5 min in 0.1-M PBS and then incubated for 10 min in a solution of 0.6% hydrogen peroxide in 10% methanol to eliminate endogenous peroxidases. After washing two times for 5 min in 0.1-M PBS, sections were then incubated for 60 min in 0.1-M PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (2% normal goat serum) and 0.3% Triton X-100 for blocking. Sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary parvalbumin antibody [1:5,000 in 0.1-M PBS containing 2% normal goat serum (Funakoshi Technical Services, Japan) and 0.3% Triton X-100]. After washing six times for 5 min in 0.1-M PBS, sections were incubated for 60 min with second antibody (1:1,200; biotinylated anti mouse immunoglobulin G; Funakoshi Technical Services] followed by amplification with an avidin–biotin complex (Funakoshi Technical Services). Peroxidase was visualized using the chromogen diaminobenzidine (Funakoshi Technical Services), intensified with nickel chloride, and counterstained with toluidine blue. Coronal sections omitting the primary antibody were routinely developed to ensure that any observed staining was due to parvalbumin. Animals of each gender from each group were processed for immunohistochemistry at a given time to avoid slight procedural differences.

Slides from animals of each gender from the two groups were randomized and coded such that all subsequent procedures were carried out blind. Coverslips were examined with an upright microscope (Olympus BX 50) equipped with a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (3 CCD Color Video Camera Model DXC-930, Sony), and analyzed with microsoft computer imaging device software (MCID) (version 7.0). Parvalbumin-positive cell counts in the medial prefrontal cortex (Bregma +3.2 mm according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson 1997) were made bilaterally in six fields per coverslip with the aid of a grid in the microscope eye-piece. The number of intensely labeled neurons was counted within 800 × 800-μm2 grid area. The data were expressed as the number of intensely labeled neurons per 1 mm2. Animal numbers of each group were as follows: MK-801 group (P63; male, n = 8; female, n = 8), saline group (P63; male, n = 8; female, n = 8); MK-801 group (P35; male, n = 7; female, n = 8), saline group (P35; male, n = 7; female, n = 8).

Distribution of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons on P63 and P35 in each gender was analyzed. As shown in Fig. 4b, the ratio of parvalbumin-positive cell number in deep layer (V and VI) to that in superficial layer (I, II, and III) in the area “500 μm × L μm” (according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson 1997) was calculated. The parvalbumin-positive cell number in the superficial or deep layers in the area “500 μm × L μm” was shown in Table 1.

Behavioral study

Experiment 1: sensitivity to PCP

Different animals were used for the experiment on P63 and P35. Rats for the experiment on P63 were randomly assigned to one of the following four groups. MK801/PCP (male, n = 6; female, n = 8) and saline/PCP (male, n = 6; female, n = 7) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P63, these two groups were injected with PCP (7.5 mg/kg, i.p.). MK801/saline (male, n = 7; female, n = 8) and saline/saline (male, n = 6; female, n = 7) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P63, these two groups were injected with saline. The animals were injected with PCP or saline in activity chambers, and locomotor activity was measured.

The rats for the experiment on P35 were randomly assigned to one of the following four groups. MK801/PCP (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) and saline/PCP (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P35, these two groups were injected with PCP (7.5 mg/kg, i.p.). MK801/saline (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) and saline/saline (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P35, these two groups were injected with saline.

Experiment 2

Dose response to PCP

Male animals were randomly assigned to one of the following four groups. MK801/PCP [2.5 mg/kg (n = 7) or 5.0 mg/kg (n = 7)], saline/PCP [2.5 mg/kg (n = 7) or 5.0 mg/kg (n = 7)], MK801/saline (n = 7), and saline/saline (n = 6) groups. On P63, MK801/PCP and saline/PCP groups were injected with PCP (2.5 or 5.0 mg/kg), and MK801/saline and saline/saline groups were injected with saline.

Reversal effect of a GABAA receptor agonist, muscimol on enhanced sensitivity to PCP

The male animals were randomly assigned to one of four groups. MK801/Veh/PCP (5.0 or 7.5 mg/kg), MK801/musc (0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg)/PCP (5.0 or 7.5 mg/kg), saline/musc (0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg)/PCP (5.0 or 7.5 mg/kg), and saline/Veh/PCP (5.0 or 7.5 mg/kg) groups. On P63, MK801/Veh/PCP (5.0 mg/kg; n = 7), MK801/musc (0.5 mg/kg)/PCP (5.0 mg/kg; n = 7), saline/musc (0.5 mg/kg)/PCP (5.0 mg/kg; n = 7), and saline/Veh/PCP (0.5 mg/kg; n = 7) groups were injected with PCP (5.0 mg/kg; black arrow) 20 min after muscimol (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle injection (white arrow). On P63, MK801/Veh/PCP (7.5 mg/kg; n = 7), MK801/musc (1.0 mg/kg)/PCP (7.5 mg/kg; n = 7), saline/musc (1.0 mg/kg)/PCP (7.5 mg/kg; n = 7), and saline/Veh/PCP (7.5 mg/kg; n = 7) groups were injected with PCP (7.5 mg/kg; black arrow) 20 min after muscimol (0.75 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle injection (white arrow).

Experiment 3: sensitivity to METH

Different animals were used for the experiment on P63 and P35. The rats for the experiment on P63 were randomly assigned to one of the following four groups. MK801/METH (male, n = 6; female, n = 7) and saline/METH (male, n = 6; female, n = 8) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P63, repeated administration with METH (1 mg/kg, s.c.; once in a day, total of five times on every other day) to these two groups was started. MK801/saline (male, n = 6; female, n = 8) and saline/saline (male, n = 6; female, n = 8) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P63, repeated administration with saline (once in a day, total of five times on every other day) to these two groups was started. Locomotor activity was measured at the first (on P63), third (on P67), and fifth injection (on P71).

The rats for the experiment on P35 were randomly assigned to one of the following four groups. MK801/METH (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) and saline/METH (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P35, repeated administration with METH (1 mg/kg, s.c.; once in a day, total of five times on every other day) to these two groups was started. MK801/saline (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) and saline/saline (male, n = 6; female, n = 6) groups were prenatally treated with MK-801 and saline, respectively, from E15 to E18. On P35, repeated administration with saline (once in a day, total of five times on every other day) to these two groups was started. Locomotor activity was measured at the first (on P35), third (on P39), and fifth injection (on P43).

Experiment 4: Dose response to METH

Male animals were randomly assigned to one of the following four groups. MK801/METH (0.3 mg/kg), saline/METH (0.3 mg/kg), MK801/METH (0.5 mg/kg), and saline/METH (0.5 mg/kg) groups. On P63, repeated administration with 0.3 and 0.5 mg/kg of METH (once in a day, total of five times on every other day) to MK801/METH (0.3 mg/kg; n = 6), saline/METH (0.3 mg/kg; n = 6) groups, and to MK801/METH (0.5 mg/kg; n = 7), saline/METH (0.5 mg/kg; n = 7) groups were started, respectively.

Measurement of locomotor activity

The observation room was located near the animal room and kept under the same conditions. The home cage for each rat was moved to an observation room and placed under the sensor. Measurement of locomotor activity began after 2-h habituation period by using an apparatus with an infrared sensor that detects thermal radiation from animal (Supermex; Muromachi Kikai, Tokyo, Japan). Horizontal movements of the rat were digitized and fed into a computer every 10 min. Locomotion predominantly contributed to the count, but repetitive rearing and other nonspecific body movements could contribute to the count when these movements had substantial horizontal components.

Statistics

Data from counts of parvalbumin-positive neurons, ratio of deep to superficial layer parvalbumin-positive cells and dose response to METH (0.3 and 0.5 mg/kg) were analyzed by an unpaired t test (p < 0.05). Data from locomotor activity in the PCP experiments and cumulated counts for locomotor activity in the METH experiments were analyzed by a repeated two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using treatment group as the between variable and time as the repeated measure variable (defined as p < 0.05). Then, a one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Duncan test was used to determine which group significantly differed from the others (p < 0.05). Furthermore, a one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc test was used to analyze the difference of cumulated counts of locomotor activity between on the fifth injection and on the first injection (p < 0.05).

Results

Immunohistochemical study

On P63, parvalbumin-positive neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of male (Fig. 1a) and female (Fig. 1b) rats exposed to MK-801 prenatally were decreased as compared to the animals treated with saline (unpaired t test). On P35, parvalbumin-positive neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of male (Fig. 1c) and female (Fig. 1d) rats prenatally exposed to MK-801 were decreased as compared to the animals treated with saline (unpaired t test). Figure 2 shows representative for the photograph of 30-μm coronal sections through the medial prefrontal cortex of male rats on P63 which were prenatally treated with saline (Fig. 2a, a lower magnification; Fig. 2b, a higher magnification), and MK-801 (Fig. 2c, a lower magnification; Fig. 2d, a higher magnification). Sections are matched for anatomical location and are representative of their respective group. Figure 3 shows representative for the photograph of 30 μm coronal sections through the medial prefrontal cortex of male rats on P35, which were prenatally treated with saline (Fig. 3a, a lower magnification; Fig. 3b, a higher magnification) and MK-801 (Fig. 3c, a lower magnification; Fig. 3d, a higher magnification). Not only at P63 but also P35, quantitative reductions in parvalbumin-positive neuronal number were seen in the prenatally MK-801-exposed rat as compared to the prenatally saline treated control.

On both P63 and P35, the ratio in parvalbumin-positive neuronal density in the deep (V and VI) to superficial (I, II, and III) layer of animals prenatally exposed to MK-801 was lower than the ratio of animals prenatally treated with saline (Fig. 4a). These results suggest that prenatal exposure to MK-801 changed distribution of parvalbumin-positive neurons. Figure 4b shows the method for the analysis of laminar distribution of parvalbumin-positive neurons. As shown in Table 1, on both P63 and P35, parvalbumin-positive cell number only in the superficial but not deep layers of male and female animals that were prenatally exposed to MK-801 was lower than that of animals prenatally treated with saline.

Ratio of the density of parvalbumin-positive cells in the deep (V and VI) to superficial (I, II, and III) layers. Asterisk: p < 0.05, MK-801 group vs saline group; number sign: p < 0.01, MK-801 group vs saline group (unpaired t test). The diagram of the area in the mPFC (according to the rat atlas of Paxinos and Watson 1997) settled for the analysis of the ratio of parvalbumin-positive cell number in the deep layers (V and VI) to the ratio in the superficial layers (I, II, and III)

Behavioral study

For the data from male postpubertal offspring (Fig. 5a), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(27, 189) = 3.92, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 21) = 7.78, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(9, 189) = 8.79, p < 0.01]. For the data from female postpubertal offspring (Fig. 5b), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(27, 234) = 10.32, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 26) = 15.98, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(9, 234) = 26.00, p < 0.01]. For the data from both male and female adult offspring on P63, the post hoc Duncan test revealed that PCP-induced hyperlocomotion of MK801/PCP group was larger than that of saline/PCP group, and revealed that PCP-induced hyperlocomotion of MK/PCP group or saline/PCP group was larger than that of saline/saline group.

Effect of prenatal exposure to MK-801 on PCP (7.5 mg/kg)-induced hyperlocomotion of male and female offspring on P63 and P35. a p < 0.05, MK801/PCP group vs saline/PCP group; b p < 0.01, MK801/PCP group vs saline/PCP group; asterisk: p < 0.05, vs saline/saline group; number sign: p < 0.01, vs saline/saline group (post hoc test)

For the data from male juvenile offspring (Fig. 5c), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(27, 180) = 3.28, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 20) = 15.81, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(9, 180) = 14.35, p < 0.01]. For the data from female juvenile offspring (Fig. 5d), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(27, 180) = 3.11, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 20) = 12.87, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(9, 180) = 6.01, p < 0.01]. For the data from both male and female juvenile offspring on P35, the post hoc Duncan test revealed that there was no difference between MK801/PCP group and saline/PCP group, and revealed that PCP-induced hyperlocomotion of MK801/PCP group or saline/PCP group was larger than that of saline/saline group.

For the data from response to 2.5 mg/kg of PCP of postpubertal male offspring (Fig. 6a), a repeated two-way ANOVA did not indicate a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(27, 207) = 1.01, p = 0.45], and indicated a significant effect of group [F(3, 23) = 4.22, p < 0.05], and an effect of time [F(9, 207) = 18.18, p < 0.01]. For the data from response to 5.0 mg/kg of PCP of postpubertal male offspring (Fig. 6b), a repeated two-way ANOVA did not indicate a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(27, 207) = 1.35, p = 0.13], and indicated a significant effect of group [F(3, 23) = 7.27, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(9, 207) = 3.69, p < 0.01]. The post hoc Duncan test indicated that 5.0 mg/kg but not 2.5 mg/kg of PCP indicated an enhanced response to PCP in the postpubertal offspring prenatally exposed to MK-801.

Dose response to PCP (2.5 and 5.0 mg/kg), and c, d reversal effect of muscimol (0.5 and 1.0 mg/kg) on an enhanced response to PCP (5.0 and 7.5 mg/kg). Asterisk: p < 0.05, MK801/PCP (2.5) group vs saline/saline group; saline/PCP (2.5) group vs saline/saline group; number sign: p < 0.01, MK801/PCP (2.5) group vs saline/saline group (post hoc test); asterisk: p < 0.05, MK801/PCP (5.0) group vs saline/saline group; saline/PCP (5.0) group vs saline/saline group; number sign: p < 0.01, MK801/PCP (5.0) group vs saline/saline group; a p < 0.05, MK801/PCP (5.0) group vs saline/PCP (5.0) group; b p < 0.01, MK801/PCP (5.0) group vs Saline/PCP (5.0) group (post hoc test); asterisk: p < 0.05, MK801/Veh/PCP (5.0) group vs saline/Veh/PCP (5.0) group; MK801/musc (0.5)/PCP (5.0) group vs saline/Veh/PCP (5.0) group; number sign: p < 0.01, MK801/Veh/PCP (5.0) group vs saline/Veh/PCP (5.0) group; a p < 0.05, MK801/musc (0.5)/PCP (5.0) group vs MK801/Veh/PCP (5.0) group; b p < 0.01, MK801/musc/PCP (5.0) group vs MK801/Veh/ PCP (5.0) group (post hoc test); White arrow: vehicle or muscimol (0.5) injection, black arrow: PCP(5.0) injection. asterisk: p < 0.05, MK801/Veh/PCP (7.5) group vs saline/Veh/PCP(7.5) group; MK801/musc (1.0)/PCP (7.5) group vs saline/Veh/PCP (7.5) group; number sign: p < 0.01, MK801/Veh/PCP (7.5) group vs saline/Veh/PCP (7.5) group; a p < 0.05, MK801/musc (1.0)/PCP (7.5) group vs MK801/Veh/PCP (7.5) group; b p < 0.01, MK801/musc/PCP (7.5) group vs MK801/Veh/ PCP (7.5) group (post hoc test). White arrow: vehicle or muscimol (1.0) injection, black arrow: PCP (7.5) injection

For the data from an effect of muscimol (0.5 mg/kg) on an enhanced response to PCP(5.0 mg/kg) in postpubertal male offspring prenatally exposed to MK-801 (Fig. 6c), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(33, 264) = 1.87, p < 0.05], an effect of group [F(3, 24) = 5.00, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(11, 264) = 7.35, p < 0.01]. For the data from an effect of muscimol (1.0 mg/kg) on an enhanced response to PCP(7.5 mg/kg) in postpubertal male offspring prenatally exposed to MK-801 (Fig. 6d), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(33, 264) = 2.45, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 24) = 3.24, p < 0.05], and an effect of time [F(11, 264) = 17.62, p < 0.01]. The post hoc Duncan test indicated that 0.5 mg/kg of muscimol attenuated or reversed an enhanced response to PCP (5.0 mg/kg) and 1.0 mg/kg of muscimol reversed an enhanced response to PCP (7.5 mg/kg) in the postpubertal male offspring prenatally exposed to MK-801.

For the data from male postpubertal offspring (Fig. 7a), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(6, 40) = 8.14, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 20) = 42.00, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(2, 40) = 12.61, p < 0.01]. For the data from female postpubertal offspring (Fig. 7b), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(6, 54) = 2.80, p < 0.05], an effect of group [F(3, 27) = 56.95, p < 0.01, and an effect of time [F(2, 54) = 7.68, p < 0.01]. For the data from both male and female adult offspring, the post hoc Duncan test indicated that cumulated counts for locomotion of both MK801/METH group and saline/METH group at the fifth injection were larger than those at the first injection, and indicated that there was no difference of cumulated counts for locomotion between MK801/METH group and saline/METH group at any time of injection.

Effect of prenatal exposure to MK-801 on the development of behavioral sensitization to METH (1 mg/kg) of male and female offspring from P63 and P35. a p < 0.05, fifth injection, third injection vs first injection; b p < 0.01, fifth injection vs first injection, third injection vs first injection; N.S. not significant, MK801/METH group vs saline/METH group (post hoc test)

For the data from male juvenile offspring (Fig. 7c), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(6, 40) = 7.26, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 20) = 68.43, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(2, 40) = 11.37, p < 0.01]. For the data from female juvenile offspring (Fig. 7d), a repeated two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of group × time interaction [F(6, 40) = 5.54, p < 0.01], an effect of group [F(3, 20) = 221.45, p < 0.01], and an effect of time [F(2, 40) = 12.91, p < 0.01]. For the data from both male and female juvenile offspring, the post hoc Duncan test indicated that cumulated counts for locomotion of both MK801/METH group and saline/METH group at the fifth injection were larger than those at the first injection and indicated that there was no difference of cumulated counts for locomotion between MK801/METH group and Saline/METH group at any time of injection.

For data from dose response to METH (0.3 and 0.5 mg/kg), an unpaired t test indicated that cumulated counts for locomotion of MK801/METH(0.3) and saline/METH(0.3) groups, and MK801/METH(0.3) and saline/METH(0.5) groups at fifth injection were larger than those at first injection (Fig. 8). Furthermore, this test indicated that there was no difference of cumulated counts for locomotion between MK801/METH and saline/METH groups both at 0.3 and 0.5 mg/kg of METH injection.

Dose response to an acute effect of METH (0.3 and 0.5 mg/kg) and a development of behavioral sensitization to METH (0.3 and 0.5 mg/kg). a p < 0.05, fifth injection vs first injection; third injection vs first injection; N.S. not significant, MK801/METH (0.3) group vs saline/METH (0.3) group; MK801/METH (0.5) group vs saline/METH (0.5) group (unpaired t test)

There were no differences of body weight of dams and pups between MK-801 group and saline group (Table 2).

Discussion

Prenatal exposure to the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 decreased the density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in male and female medial prefrontal cortex not only on P63 but also P35. This reduction in parvalbumin-positive neurons could be mediated by cell death induced by MK-801 administered prenatally, reduced expression of parvalbumin in living cells, or interference with the neurogenesis of interneurons. The present immunohistochemical findings cannot clarify which mechanism is responsible for the reduction in parvalbumin-positive neurons. We cannot definitively conclude that the decrease in immunoreactivity observed reflects a reduction in parvalbumin-positive GABAergic cell number on the basis of immunohistochemical findings alone. The reduction in density of parvalbumin-expressing GABAergic interneurons we observed may be due to changes in the volume of medial prefrontal cortex and/or the diameters of parvalbumin-expressing cells (Beasley and Reynolds 1997; Moore et al. 1998).

MK-801 exposure during the cell-proliferative phase (E15–E18) but not the postproliferative phase (E18–E21) induces long-lasting decrease in parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the rat striatum (on P35 or P42); this decrease is mediated by blocking of NMDA receptors (Sadikot et al. 1998). Prenatal ethanol exposure reduces the number of parvalbumin-immunoreactive GABAergic neurons in adult rat cingulate cortex (Moore et al. 1998); this reduction may be mediated by blocking of NMDA receptors and/or stimulation of GABAA receptors (Ikonomidou et al. 2000). The fact that parvalbumin-positive neurons of the cortex are derived from the same region as striatal parvalbumin-positive neurons (the medial ganglion eminence; Metin et al. 2006) suggests the possibility that the effects of NMDA receptor blockade on proliferation of striatal parvalbumin-positive neurons may be generalized to include cortical parvalbumin-positive neurons as well, and that glutamate influences the proliferation of parvalbumin-expressing GABAergic interneurons via NMDA-receptor-mediated excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission.

In the present study, on both P63 and P35, the ratio of parvalbumin-positive neuronal density in the deep (V and VI) to that in the superficial (I, II, and III) layers in animals prenatally exposed to MK-801 was lower than that in animals prenatally treated with saline. The low ratio was due to a decrease in the number of parvalbumin-positive cells in the deep but not superficial layers. Considering that glutamate, acting via NMDA receptors, plays an important role in the migration of immature neurons (Komuro and Rakic 1993; Behar et al. 1999; Csillik et al. 2002), we can speculate that prenatal blockade of NMDA receptors may have disturbed the migration of parvalbumin-expressing GABAergic interneurons.

NMDA receptor antagonists have neurotoxic effects in various regions of cortex in adult rats (Allen and Iversen 1990). In contrast, fetal rats are insensitive to the cerebrocortical neurotoxic effects of NMDA receptor antagonists (Farber et al. 1995). However, expression of the neuroprotective protein parvalbumin does not begin until the first postnatal week (Alcantara et al. 1993), yielding ‘a window of vulnerability’ during which these neurons may be particularly sensitive to excitatory damage. The prenatal MK-801 exposure-induced, long-lasting reduction in parvalbumin-expressing cells may thus be mediated by NMDA receptor antagonist-induced neurotoxic effects on immature parvalbumin-expressing cells.

Prenatal exposure to MK-801 enhanced the PCP-induced hyperlocomotion of male and female offspring on P63. PCP-induced hyperlocomotion is mediated by the blockade of NMDA receptors on GABAergic interneurons in medial prefrontal cortex (Yonezawa et al. 1998). The primary site of pharmacological action of PCP is prefrontal cortex (Jentsch et al. 1998). GABAA receptor agonists such as muscimol and imidazole acetic acid block PCP-induced hyperlocomotion (Freed et al. 1980). GABA transaminase inhibitors such as vigabatrin and (s)-4-allenyl GABA, which increase brain GABA concentrations, antagonize PCP-induced hyperlocomotion (Seiler and Grauffel 1992). These findings suggest the hypothesis that in prenatally MK-801-exposed offspring, the reduction in density of parvalbumin-positive GABAergic neurons in medial prefrontal cortex on P63 enhances PCP-induced hyperlocomotion, as prenatal MK-801 exposure-induced GABAergic deficit enhances PCP-induced attenuation of GABAergic transmission via blockade of NMDA receptors on GABAergic interneurons. In fact, in the present study, a GABAA receptor agonist, muscimol, reversed the enhancement of response to PCP in postpubertal animals prenatally exposed to MK-801.

In the present study, similar to previous studies (Honack and Loscher 1993; Moy and Breese 2002), behavioral sensitivity to PCP was higher in female than male animals. Although there was the difference of sensitivity to PCP between male and female animals, enhanced response to PCP was similarly induced in male and female adult rats that were prenatally exposed to MK-801.

Prenatal exposure to MK-801-induced GABAergic deficit had no effect on sensitivity to the acute effects of METH at the first injection on P63 or the development of behavioral sensitization to METH from P63. Prenatal exposure to MK-801 had no effect on PCP-induced hyperlocomotion of male or female rats on P35, and had no effect on sensitivity to the acute effects of METH at the first injection or the development of behavioral sensitization to METH from P35.

An NMDA receptor antagonist, ketamine activates psychotic symptoms in schizophrenic patients (Mechri et al. 2001). Although haloperidol, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, fails to block the ketamine-induced worsening of psychotic symptoms (Lahti et al. 1995), clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic that is effective to the treatment-resistant schizophrenia, improves ketamine-induced activation of positive symptoms in schizophrenic patients (Malhotra et al. 1997). Psychosis that is induced by chronic abuse of METH is effectively improved by haloperidol (Sato et al. 1983). Although haloperidol more potently blocks hyperlocomotion elicited by AMPH than PCP, PCP-induced hyperlocomotion is more potently blocked by clozapine than haloperidol (Maurel-Remy et al. 1995). Therefore, PCP-induced hyperlocomotion and METH/AMPH-induced hyperlocomotion can model treatment-resistant and dopamine D2 receptor antagonist-responsive pathophysiology of schizophrenia, respectively.

The findings of the present study do not enable clear determination why prenatal exposure to MK-801 enhanced PCP-induced hyperlocomotion on P63 but not on P35. In the present study, reduction in the density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in medial prefrontal cortex was found even on P35. Notably, Olney and Farber (1995) hypothesized the following: GABAergic neurons that are destined to be innervated by glutamate via NMDA receptors in the adult central nervous system may express NMDA receptors in the fetal brain in utero that reach peak sensitivity to excitotoxic stimulation at a relatively early stage of pregnancy. This excitotoxic insult during pregnancy might selectively delete NMDA receptor-bearing GABAergic neurons, setting the stage for expression of an NMDA receptor antagonist-induced syndrome in early adulthood.

Numerous neurodevelopmental animal models of schizophrenia have been developed. Excitotoxic lesions and reversible inactivation of the ventral hippocampus in neonatal rats enhance MK-801- and AMPH-induced hyperlocomotion in adult but not juvenile rats (Al-Amin et al. 2001; Lipska et al. 2002). The present study has shown for the first time that prenatal exposure to MK-801 induces a deficit in GABAergic neuronal development in the mPFC not only on P63 but also on P35, enhances PCP-induced hyperlocomotion in adult but not juvenile rats, but does not enhance sensitivity to the acute effects of METH or the development of behavioral sensitization to METH in either adult or juvenile rats. The prenatal MK-801 exposure model is thus consistent with the neonatal ventral hippocampus dysfunction model, in the observation of enhancement of NMDA receptor antagonist-induced hyperlocomotion, but inconsistent with it in lack of effect on METH/AMPH-induced hyperlocomotion.

Postnatal PCP treatment minimally affects PCP-induced hyperlocomotion in male and female adult animals (Sircar and Soliman 2003), and postnatal MK-801 treatment increases spontaneous locomotor activity in female but not in male adult animals (Harris et al. 2003). These findings are quite different from those of the present study and lacks histological information on neurodevelopment. Although postnatal NMDA-receptor-mediated neurotransmission may play an important role for the neurodevelopment, prenatal period from E15 to E18, during which animals were exposed to MK-801 in the present study, is the most critical for parvalbumin-positive cell proliferation as mentioned previously (Sadikot et al. 1998).

In conclusion, prenatal exposure to the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 reduced the density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in male and female rat medial prefrontal cortex not only on P63 but also on P35. In both male and female offspring, prenatal exposure to MK-801 enhanced PCP-induced hyperlocomotion but did not enhance the acute effects of METH on P63 or the development of behavioral sensitization to METH from P63. Prenatal exposure to MK-801 had no effect, in male or female offspring, on PCP-induced hyperlocomotion on P35. Furthermore, prenatal exposure to MK-801 did not alter the acute effects of METH on P35 or the development of behavioral sensitization to METH from P35. In prenatally MK-801-exposed offspring, the reduction in density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in medial prefrontal cortex on P63 may be related to the enhancement of PCP-induced hyperlocomotion. This GABAergic neurodevelopmental deficit and the enhancement of PCP-induced hyperlocomotion but not METH observed in prenatally MK-801-exposed animals may be useful as a new model of the neurodevelopmental process of the pathogenesis of schizophrenia via an NMDA receptor-mediated hypoglutamatergic mechanism, and might enable the development of treatments for the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist-resistant pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

References

Abekawa T, Honda M, Ito K, Koyama T (2003) Effects of NRA0045, a novel potent antagonist at dopamine D4, 5-HT2A, and α1 adrenaline receptors, and NRA0160, a selective D4 receptor antagonist, on phencyclidine-induced behavior and glutamate release in rats. Psychopharmacology 169:247–256

Al-Amin HA, Weickert CS, Weinberger DR, Lipska BK (2001) Delayed onset of enhanced MK-801-induced motor hyperactivity after neonatal lesions of the rat ventral hippocampus. Biol Psychiatry 49:528–539

Alcantara S, Ferrer I, Soriano E (1993) Postnatal development of parvalbumin and calbindin D28K immunoreactivities in the cerebral cortex of the rat. Anat Embryol Berl 188:63–73

Allen HL, Iversen LL (1990) Phencyclidine, dizocilpine and cerebrocortical neurons. Science 247:221

Bailey CDC, Brien JF, Reynolds JN (2001) Chronic prenatal ethanol exposure Increases GABAA receptor subunit protein expression in the adult guinea pig cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 21:4381–4389

Beasley CL, Reynolds GP (1997) Parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons are reduced in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Schizophr Res 24:349–355

Beasley CL, Zhang ZJ, Patten I, Reynolds GP (2002) Selective deficits in prefrontal cortical GABAergic neurons in schizophrenia defined by the presence of calcium-binding proteins. Biol Psychiatry 52:708–715

Behar TN, Scott CA, Greene CL, Wen X, Smith SV, Maric D, Liu QY, Colton CA, Barker JL (1999) Glutamate acting at NMDA receptors stimulates embryonic cortical neuronal migration. J Neurosci 19:4449–4461

Benes FM, Bird ED (1987) An analysis of the arrangement of neurons in the cingulate cortex of schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44:608–616

Benes FM, McSparren J, Bird ED, SanGiovanni JP, Vincent SL (1991) Deficits in small interneurons in prefrontal and cingulated cortices of schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:996–1001

Benes FM, Vincent SL, Marie A, Khan Y (1996) Up-regulation of GABAA receptor binding on neurons of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Neuroscience 74:1021–1031

Bogerts B, Ashtari M, Degreef G, Alvir JMJ, Bilder RM, Lieberman JA (1990) Reduced temporal limbic structure volumes on magnetic resonance images in first episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 35:1–13

Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, Tracy KA, Wolnlak P, Sommerville W (2003) Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:182–192

Celio MR (1990) Calbindin D-28K and parvalbumin in the rat nervous system. Neuroscience 35:375–475

Corbett R, Camacho F, Woods AT (1995): Antipsychotic agents antagonize non-competitive N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist-induced behaviors. Psychopharmacology 120:67–74

Csillik A, Okuno E, Csillik B, Knyihar E, Vecsei L (2002) Expression of kynurenine aminotransferase in the subplate of the rat and its possible role in the regulation of programmed cell death. Cereb Cortex 12:1193–1201

Cunningham MO, Jones RSG (2000) The anticonvulsant, lamotrigine decreases spontaneous glutamate release but increases spontaneous GABA release in the rat entorhinal cortex in vitro. Neuropharmacology 39:2139–2146

Demeulemeester H, Vandesande F, Orban GA, Brando C (1988) Heterogenity of GABAergic cells in cat visual cortex. J Neurosci 8:988–1000

Dursun SM, Deakin JF (2001) Augmenting antipsychotic treatment with lamotrigine or topiramate in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a naturalistic case-series outcome study. J Psychopharmacol 15:297–301

Farber NB, Wozniak DF, Price MT, Labruyere J, Huss J, St Peter H, Olney JW (1995) Age-specific neurotoxicity in the rat associated with NMDA receptor blockade: potential relevance to schizophrenia? Biol Psychiatry 38:788–796

Freed WJ, Weinberger DR, Bing LA, Wyatt RJ (1980) Neuropharmacological studies of phencyclidine (PCP)-induced behavioral stimulation in mice. Psychopharmacology 71:291–297

Gleason SD, Shannon HE (1997) Blockade of phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion by olanzapine, clozapine and serotonin receptor subtype selective antagonists in mice. Psychopharmacology 129:79–84

Harris LW, Sharp T, Gartlon J, Jones DNC, Harrison PJ (2003) Long-term behavioural, molecular and morphological effects of neonatal NMDA receptor antagonism. Eur J Neurosci 18:1706–1710

Honack D, Loscher W (1993) Sex differences in NMDA receptor mediated responses in rats. Brain Res 620:167–170

Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Wozniak DF, Koch C, Genz K, Pierce MT, Stefovska V, Horster F, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Olney JW (2000) Ethanol-induced apoptosis neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science 287:1056–1060

Javitt DC, Zukin SR (1991) Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 148:1301–1308

Jentsch JD, Tran A, Taylor JR, Roth RH (1998) Prefrontal cortical involvement in phencyclidine-induced activation of mesolimbic dopamine system: behavioral and neurochemical evidence. Psychopharmacology 138:89–95

Kalivas PW, Hooks MS, Sorg B (1993) The pharmacology and neural circuitry of sensitization to psychostimulants. Behav Pharmacol 4:315–334

Komuro H, Rakic P (1993) Modulation of neuronal migration by NMDA receptors. Science 260:95–97

Lahti AC, Koffel B, LaPorte D, Tamminga CA (1995) Subanesthetic doses of ketamine stimulates psychosis in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 13:9–19

Leach MJ, Marden CM, Miller AA (1986) Pharmacological studies on lamotrigine, a novel potential antiepileptic drug: II. Neurochemical studies on the mechanism of action. Epilepsia 27:490–497

Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW (2005) Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Neuroscience 6:312–324

Lipska BK, Luu S, Halim ND, Weinberger DR (2002) Behavioral effects of neonatal And adult excitotoxic lesions of the mediodorsal thalamus in the adult rat. Behav Brain Res 141:105–111

Loscher W (1999) Valproate: a reappraisal of its pharmacodynamic properties and mechanisms of action. Prog Neurobiol 58:31–59

Malhotra AK, Adler CM, Kennison SD, Elman I, Picker D, Breier A (1997) Clozapine blunts N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist-induced psychosis: a study with ketamine. Biol Psychiatry 42:664–668

Maurel-Remy S, Bervoets K, Millan MJ (1995) Blockade of phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion by clozapine and MDL 100,907 in rats reflects antagonism of 5-HT2A receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 280:R9–R11

McPhalen CA, Sielecki AR, Santarsiero BD, James MN (1994): refined crystal structure of rat parvalbumin, a mammalian alpha-lineage parvalbumin, at 2.0 A solution. J Mol Biol 235:718–732

Mechri A, Saoud M, Khiari G, d’Amato T, Dalery J, Gaha L (2001) Glutamatergic hypothesis of schizophrenia: clinical research studies with ketamine. Encephale 27:53–59

Metin C, Baudoin JP, Rakic S, Parnavelas JG (2006) Cell and molecular mechanisms involved in the migration of cortical interneurons. Eur J Neurosci 23:894–900

Millan MJ (2005) N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors as a target for improved antipsychotic agents: novel insight and clinical perspectives. Psychopharmacology 179:30–53

Moore DB, Quintero MA, Ruygrok AC, Walker DW, Heaton MB (1998) Prenatal ethanol exposure reduces parvalbumin-immunoreactive GABAergic neuronal number in the adult rat cingulated cortex. Neurosci Lett 249:25–28

Moy SS, Breese GR (2002) Phencyclidine supersensitivity in rats with neonatal dopamine loss. Psychopharmacology 161:255–262

Olney JW, Farber NB (1995) Glutamate receptor dysfunction and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:998–1007

Paxinos G, Watson C (1997) The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, 3rd edn. Academic, USA

Pierce RC, Kalivas PW (1997) A circuitry model of the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Brain Res Rev 25:192–216

Plogmann D, Celio MR (1993) Intracellular concentration of parvalbumin in nerve cells. Brain Res 600:273–279

Roberts GW (1991) Schizophrenia: a neuropathological perspective. Br J Psychiatry 158:8–17

Robinson TE, Becker JB (1986) Enduring changes in brain and behavior by chronic amphetamine administration: a review and evaluation of animal models of amphetamine psychosis. Brain Res Rev 11:157–198

Sadikot AF, Burhan AM, Belanger M-C, Sasseville R (1998) NMDA receptor antagonist influences early development of GABAergic interneurons in the mammalian striatum. Dev Brain Res 105:35–42

Sato M, Chen C-C, Akiyama K, Otsuki S (1983) Acute exacerbation of paranoid psychotic state after long-term abstinence in patients with previous methamphetamine psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 18:429–440

Seiler N, Grauffel C (1992) Antagonism of phencyclidine-induced hyperactivity in mice by elevated brain GABA concentrations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 41:603–606

Sircar R, Soliman KFA (2003) Effects of postnatal PCP treatment on locomotor behavior and striatal D2 receptor. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 74:943–952

Szeszko PR, Bilder RM, Lencz T, Pollack S, Alvir JM, Ashtari M, Wu H, Lieberman JA (1999) Investigation of frontal lobe subregions in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 90:1–15

Tiihonen J, Hallikainen T, Ryynanen OP, Repo-Tiihonen E, Kotilainen I, Eronen M, Toivonen P, Wahlbeck K (2003) Lamotrigine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. Biol Psychiatry 54:1241–1248

Vriend JP, Alexiuk NA (1996) Effects of valproate on amino acid and monoamine concentration in striatum of audiogenic seizure-prone Balb/c mice. Mol Chem Neuropathol 27:307–324

Wassef AA, Dott SG, Harris A, Brown A, O’Boyle M, Meyer WJ III, Rose RM (2000) Randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 20:357–361

Yonezawa Y, Kuroki T, Kawahara T, Tashiro N, Uchimura H (1998) Involvement of γ-aminobutyric acid neurotransmission in phencyclidine-induced dopamine release in the medial prefrontal cortex. Eur J Pharmacol 341:45–56

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid No 14370287 and No 15591207 for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan. The authors thank Ms Akiko Kato for her technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abekawa, T., Ito, K., Nakagawa, S. et al. Prenatal exposure to an NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801 reduces density of parvalbumin-immunoreactive GABAergic neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex and enhances phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion but not behavioral sensitization to methamphetamine in postpubertal rats. Psychopharmacology 192, 303–316 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-007-0729-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-007-0729-8