Abstract

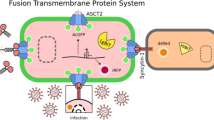

The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) binds to the chemokine receptor CXCR4 that couples to pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins of the Gi/Go-family. CXCR4 plays a role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, human immunodeficiency virus infection and various tumors, fetal development as well as endothelial progenitor and T-cell recruitment. To this end, most CXCR4 studies have focused on the cellular level. The aim of this study was to establish a reconstitution system for the human CXCR4 that allows for the analysis of receptor/G-protein coupling at the membrane level. We wished to study specifically constitutive CXCR4 activity and the G-protein-specificity of CXCR4. We co-expressed N- and C-terminally epitope-tagged human CXCR4 with various Gi/Go-proteins and regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS)-proteins in Sf9 insect cells. Expression of CXCR4, G-proteins, and RGS-proteins was verified by immunoblotting. CXCR4 coupled more effectively to Gαi1 and Gαi2 than to Gαi3 and Gαo and insect cell G-proteins as assessed by SDF-1α-stimulated high-affinity steady-state GTP hydrolysis. The RGS-proteins RGS4 and GAIP enhanced SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis. SDF-1α stimulated [35S]guanosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate (GTPγS) binding to Gαi2. RGS4 did not enhance GTPγS binding. Na+ salts of halides did not reduce basal GTPase activity. The bicyclam, 1-[[1,4,8,11-tetrazacyclotetradec-1-ylmethyl)phenyl]methyl]-1,4,8,11-tetrazacyclotetradecane (AMD3100), acted as CXCR4 antagonist but was devoid of inverse agonistic activity. Halides reduced the maximum SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis in the order of efficacy I− > Br− > Cl−. In addition, salts reduced the potency of SDF-1α at activating GTP hydrolysis. From our data, we conclude the following: (1) Sf9 cells are a suitable system for expression of functionally intact human CXCR4; (2) Human CXCR4 couples effectively to Gαi1 and Gαi2; (3) There is no evidence for constitutive activity of CXCR4; (4) RGS-proteins enhance agonist-stimulated GTP hydrolysis, showing that GTP hydrolysis becomes rate-limiting in the presence of SDF-1α; (5) By analogy to previous observations made for the β2-adrenoceptor coupled to Gs, the inhibitory effects of halides on agonist-stimulated GTP hydrolysis may be due to increased GDP-affinity of Gi-proteins, reducing the efficacy of CXCR4 at stimulating nucleotide exchange.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chemokines (a condensation of the terms chemoattractant and cytokine) are a family of peptide mediators that exert their biological effects via several GPCRs referred to as chemokine receptors (Murphy 2002). SDF-1α, also named CXCL12, is a basic 68 amino acid peptide that binds to the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (Murphy 2002; Tamamura et al. 2006). Ionic interactions between positively charged residues in SDF-1α and negatively charged residues in CXCR4 are critical for ligand recognition and subsequent receptor activation (Zhou and Tai 2000; Gerlach et al. 2001; Gupta et al. 2001). CXCR4 couples to pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins of the Gi/Go-family (Moepps et al. 1997, 2000; Chen et al. 1998). CXCR4 and SDF-1α are widely expressed in tissues and play an important role in fetal development, mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells, trafficking of naïve lymphocytes, and recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells and T-cells (Kucia et al. 2004; Buckingham 2006; Guyon and Nahon 2007; Hristov et al. 2007). Whereas many chemokines show promiscuity for chemokine receptors, there is high selectivity between the CXCR4/SDF-1α pair, and both the knockouts of the genes for CXCR4 and SDF-1α are embryonically lethal (Kucia et al. 2004; Buckingham 2006; Guyon and Nahon 2007).

There is evidence for a role of CXCR4 in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis as well as metastatic spread of various malignant tumors including breast, prostate, and brain tumors (Kucia et al. 2004; Tamamura et al. 2006; Kryczek et al. 2007). Most intriguingly, CXCR4 serves as a co-receptor for the entry of human immunodeficiency virus into host cells (Tamamura et al. 2006; Tsibris and Kuritzkes 2007). From all these data, it is evident that CXCR4 antagonists could be most valuable therapeutic agents for several important human diseases. The bicyclam AMD3100 prevents human deficiency virus entry into T-lymphocytes by blocking the CXCR4 co-receptor but was not further developed as a drug because of cardiotoxicity (Gerlach et al. 2001; Gupta et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2002).

Coupling of CXCR4 to pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins is well established (Chen et al. 1998; Moepps et al. 1997, 2000), but the precise Gi/Go-protein isoforms with which CXCR4 can interact, are unknown. However, given the broad organ expression of CXCR4 including the CNS (Bajetto et al. 2001; Kucia et al. 2004; Buckingham 2006; Guyon and Nahon 2007), this is an important question. Moreover, many signal transduction studies with CXCR4 have been performed with intact cells (Ganju et al. 1998; Chen et al. 1998; Ödemis et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2002; Rosenkilde et al. 2004), whereas the number of studies assessing CXCR4/G-protein coupling at the membrane level is limited (Moepps et al. 1997; Gupta et al. 2001). The membrane steady-state GTPase- and GTPγS binding assays, unlike intact cell assays, provide direct insight into GPCR/G-protein coupling (Wieland and Seifert 2005). Furthermore, several GPCRs functionally related to CXCR4, i.e., the chemoattractant receptors for formyl peptides and complement C5a, exhibit agonist-independent, i.e., constitutive activity (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998, 1999; Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001), but the extent of constitutive activity of CXCR4 is unknown. This is an important question for antagonist research, as inverse agonists, i.e., ligands abrogating the constitutive GPCR activity by stabilizing the inactive (R) state of a GPCR, may exhibit larger inhibitory effects in vivo than neutral antagonists devoid of inverse agonistic activity (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2002). Finally, previous studies showed that various chemoattractant receptors differ from each other in the kinetics of G-protein activation (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998, 1999; Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001), but the kinetics of G-protein activation by CXCR4 are unknown. The aim of this study was to establish a reconstitution system for the human CXCR4 that allows for the analysis of receptor/G-protein coupling at the membrane level. We wished to study specifically constitutive CXCR4 activity and the G-protein-specificity of CXCR4.

To achieve our aim, we expressed N-terminally FLAG-epitope and C-terminally hexahistidine-tagged human CXCR4 in Sf9 insect cells. We chose this tagging orientation to facilitate comparison of CXCR4 with GPCRs that were tagged identically and were functionally intact (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998; Seifert et al. 1998; Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001). We reconstituted CXCR4 with the Gi-proteins Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3. Gi-proteins are broadly expressed in tissues (Birnbaumer et al. 1990). We also co-expressed human CXCR4 with Gαo1 (in the following simply referred to as Gαo), the major neuronal G-protein, as CXCR4 is expressed in neuronal cells (Bajetto et al. 2001; Guyon and Nahon 2007). As Gβγ-complex, we used the combination Gβ1γ2 which is broadly expressed in tissues (Birnbaumer 2007). It is well established that Sf9 insect cells tolerate the infection with three different recombinant baculoviruses (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998; Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001). Co-expression of GPCRs along with GTPase-activating RGS proteins can enhance GPCR-mediated steady-state GTP hydrolysis (Houston et al. 2002; Ward and Milligan 2004). Because we were also interested in obtaining a sensitive expression system with a high signal-to-noise ratio for future CXCR4 antagonist development, we probed infection of Sf9 cells with four different recombinant baculoviruses. In a previous study, Moepps et al. (1997) had already reconstituted the mouse CXCR4 homologs and human CXCR4 with the G-protein Gαi2β1γ3 in Sf9 cells, measuring [35S]GTPγS binding as read-out.

Materials and methods

Materials

AMD3100 was from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany) and was dissolved as a 10-mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide. Human recombinant SDF-1α was purchased as lyophilized powder in 10 μg (1.25 nmol) aliquots from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany) and dissolved in 250 μl of double-distilled water supplemented with 0.1% (m/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA). The resulting 5 μM stock solution was further diluted into 1 μM work stock solutions. Work stock solutions were divided into 50 μl aliquots and stored at −80°C until use. Each aliquot was thawed only once, and work dilutions were prepared fresh daily in double-distilled water supplemented with 0.1% (m/v) BSA.

The anti-FLAG Ig (M1 monoclonal antibody) was from Sigma. The anti-RGS4 and anti-GAIP Igs were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-Gαi1–2 Ig and anti-Gαo Ig were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). The anti-hexahistidine Ig was from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA). The anti-Gαi-common Ig (AS266) and anti-Gβcommon Ig (AS398) were a kind gift from Dr. Bernd Nürnberg (University of Düsseldorf, Germany). [γ-32P]GTP was synthesized through enzymatic phosphorylation of GDP (Walseth and Johnson 1979). [32P]Pi (8,500–9,100 Ci/mmol orthophosphoric acid), [3H]dihydroalprenolol (85–90 Ci/mmol), and [35S]GTPγS (1100 Ci/mmol) were from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA, USA). All unlabeled nucleotides were from Roche. All restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, USA). Cloned Pfu DNA polymerase was from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA). A plasmid-encoding human CXCR4 in pcDNA3.1 was obtained from the Guthrie cDNA Resource Center (Sayre, PA, USA). Baculoviruses encoding for RGS4 and GAIP were a kind gift from Dr. Elliot Ross (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA). Baculoviruses encoding for Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 were a kind gift from Dr. Alfred. G. Gilman (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA). Baculovirus encoding for rat Gαo1 (in the following simply referred to as Gαo; Jones and Reed 1987; Graber et al. 1992) was generously provided by Dr. James C. Garrison (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA). Baculovirus encoding for Gβ1 and Gγ2 was a kind gift from Dr. Peter Gierschik (University of Ulm, Germany).

Construction of pVL 1392-SF-CXCR4-6His

The cDNA encoding for human CXCR4 with an N-terminal FLAG epitope and a C-terminal hexahistidine epitope was generated by sequential overlap-extension polymerase chain reaction (PCR) according to previously described procedures (Seifert et al. 1998; Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998; Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001). Briefly, with pGEM-3Z-SF-gpH1R as template, PCR 1A was used to amplify a DNA fragment consisting of the cleavable signal peptide from influenza hemagglutinin (S) and the FLAG epitope (F) recognized by the M1 monoclonal antibody. In PCR 1B, the DNA sequence of CXCR4 was amplified with a sense primer encoding for the FLAG epitope and the first 17 bp of CXCR4 cDNA and an antisense primer encoding for the last 15 bp of CXCR4 and a hexahistidine tag as well as an Xba I site in its 3′-extension. In PCR2, the products of PCR 1A and PCR 1B served as template, using the sense primer of PCR1A and the antisense primer of PCR1B. In this way, the cDNA encoding for human CXCR4 with an N-terminal FLAG epitope and a C-terminal hexahistidine tag (SF-CXCR4–6His) was generated. The product of PCR 2 was digested with Sac I and Xba I and directly ligated into pVL 1392-SF-β2AR-Gαi2-6His digested with Sac I and Xba I. PCR-amplified cDNA sequences were confirmed by extensive restriction enzyme digestion and enzymatic sequencing.

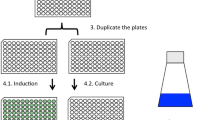

Generation of recombinant baculoviruses, cell culture, and membrane preparation

Recombinant baculovirus encoding for SF-CXCR4-6His was obtained in Sf9 cells using the BaculoGOLD transfection kit (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After initial transfection, high-titer virus stocks were generated by two sequential virus amplifications. Sf9 cells were cultured in 250 ml disposable Erlenmeyer flasks at 28°C under rotation at 125 rpm in SF 900 II medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal calf serum (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD, USA) and 0.1 mg/ml gentamicin (BioWhittaker). Cells were maintained at a density of 0.5–6.0 × 106 cells/ml. For infection, cells were sedimented by centrifugation and suspended in fresh medium. Cells were seeded at 3.0 × 106 cells/ml and infected with a 1:100 dilution of high-titer baculovirus stocks encoding for SF-CXCR4-6His, G-protein α-subunits, and G-protein βγ-subunits without or with viruses encoding for RGS-proteins. Cells were cultured for 48 h before membrane preparation. Sf9 membranes were prepared as described previously (Seifert et al. 1998), using 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml benzamidine, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin as protease inhibitors. Membranes were suspended in binding buffer (12.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 75 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4) and stored at −80°C until use. Table 1 provides an overview on the 13 different types of membranes compared in this study. The membranes listed in Table 1 were prepared on the same day, allowing for direct comparison of data. Similar data were obtained with another set of membranes.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis

Membrane proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gels containing 12% (m/v) acrylamide. Proteins were then transferred onto Immobilon-P transfer membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA; Seifert et al. 1998). Membranes were reacted with anti-hexahistidine Ig (1:5,000), anti-FLAG Ig, anti-Gαo Ig, and anti-Gαi1–2 Ig (1:1,000 each), anti-RGS4 Ig, anti-GAIP Ig, and anti-Gαcommon Ig (1:500 each) as well as anti Gβcommon Ig (1:200). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) using appropriate secondary Igs coupled to peroxidase.

[35S]GTPγS binding assay

Membranes were thawed and sedimented by a 15-min centrifugation at 4°C and 15,000×g to remove residual endogenous guanine nucleotides as far as possible. Membranes were resuspended in binding buffer (12.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA and 75 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4), supplemented with 0.05% (m/v) BSA. Each tube (total volume of 250 µl) contained 15 µg of membrane protein (Seifert et al. 1998; Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998). Tubes additionally contained 1 μM GDP and 0.4 nM [35S]GTPγS for time course experiments. For saturation experiments, tubes contained 0.2–2 nM [35S]GTPγS plus 3–18 nM unlabeled GTPγS to give the desired final ligand concentrations. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 µM GTPγS and amounted to less than 1% of total binding. Incubations were conducted for various periods of time at 25°C and shaking at 250 rpm. Bound [35S]GTPγS was separated from free [35S]GTPγS by filtration through GF/C filters, followed by three washes with 2 ml of binding buffer (4°C). Filter-bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Steady-state GTPase activity assay

Membranes were thawed, sedimented, and resuspended in 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4. Assay tubes contained Sf9 membranes (10 µg of protein/tube), 1.0 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM ATP, 100 nM GTP, 0.1 mM adenylyl imidodiphosphate, 5 mM creatine phosphate, 40 µg of creatine kinase, and 0.2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, and SDF-1α and/or AMD3100 at various concentrations (Seifert et al. 1998). Reaction mixtures additionally contained monovalent salts at various concentrations. Reaction mixtures (80 µl) were incubated for 2 min at 25°C before the addition of 20 µl of [γ-32P]GTP (0.1 µCi/tube). All stock and work dilutions of [γ-32P]GTP were prepared in 20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4. Reactions were conducted for 20 min at 25°C. Preliminary studies showed that under basal conditions and in the presence of SDF-1α, GTP hydrolysis was linear. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 900 µl of slurry consisting of 5% (m/v) activated charcoal and 50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 2.0. Charcoal-quenched reaction mixtures were centrifuged for 7 min at room temperature at 15,000×g. Six hundred microliters of the supernatant fluid of reaction mixtures were removed, and 32Pi was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Enzyme activities were corrected for spontaneous degradation of [γ-32P]GTP. Spontaneous [γ-32P]GTP degradation was determined in tubes containing all of the above described components plus a very high concentration of unlabeled GTP (1 mM) that, by competition with [γ-32P]GTP, prevents [γ-32P]GTP hydrolysis by enzymatic activities present in Sf9 membranes. Spontaneous [γ-32P]GTP degradation was <1% of the total amount of radioactivity added. The experimental conditions chosen ensured that not more than 10% of the total amount of [γ-32P]GTP added was converted to 32Pi.

Miscellaneous

Protein concentrations were determined using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). [3H]Dihydroalprenolol saturation binding was performed as described (Seifert et al. 1998). All analyses of experimental data were performed with the Prism 4 program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Expression levels of recombinant proteins were determined using the BioRad GS-710 Calibrated Imgaging Densitometer and the software tool Quantity One version 4.0.3. The statistical significance of the effects of RGS-proteins RGS4 and GAIP versus control on SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis shown in Fig. 3 was assessed using the t test.

Results and discussion

Detection of recombinant proteins in Sf9 cell membranes by immunoblotting

In Sf9 membranes, N-terminally FLAG-tagged human CXCR4 migrated as a diffuse 37-kDa protein (Fig. 1a), consistent with the GPCR being glycosylated (Zhou and Tai 1999). We also detected a less intense diffuse 75 kDa band, most likely representing CXCR4 dimers (Percherancier et al. 2005). It is unlikely that the diffuse 75 kDa band in the anti-FLAG immunoblot represents a nonspecific reactivity, as the 75-kDa band in the anti-Gαicommon immunoblot was crisp and not diffuse (Fig. 1c). The intensities of the 37- and 75 kDa bands, respectively, were similar in the various membranes. These data indicate that regardless of whether Sf9 cells were infected with CXCR4 virus alone or one, two, or even three additional baculoviruses, receptor expression was not substantially affected, greatly facilitating functional comparison of membranes. Figure 1b shows a calibration gel with increasing amounts of FLAG-tagged β2AR expressed at 7.5 pmol/mg as assessed by [3H]dihydroalprenolol saturation binding. Using this receptor as standard, CXCR4 expression was densitometrically estimated to be ∼4 pmol/mg in the various membranes.

Analysis of the expression of CXCR4 and Gα subunits in Sf9 membranes. SDS-PAGE and immunoblots were performed as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Unless stated otherwise in (b), 10 μg of membrane protein were loaded onto each lane. Numbers on the left indicate molecular masses (kDa) of marker proteins. Numbers below immunoblots designate the specific membrane studied (see Table 1 for specific protein composition). Shown are the immunoblots of gels containing 12% (m/v) acrylamide. a Anti-FLAG Ig with CXCR4-expressing membranes; b Anti-FLAG Ig with β2AR standard membrane (7.5 pmol/mg as assessed by [3H]dihydroalprenolol saturation binding; 2–15 μg of protein/lane) and one representative CXCR4 membrane; c Anti-Gαicommon Ig with CXCR4 membranes; d Anti-Gαi1,2 Ig with CXCR4 membranes; e anti-Gαo Ig with CXCR4 membranes

Figure 1c shows the expression of Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 in Sf9 membranes as detected by anti-Gαicommon Ig. Membrane 1178 was derived from cells infected with CXCR4 virus only, and there was no immunoreactive band in the 40 kDa region. The anti-Gαicommon Ig also did not recognize Gαo (membranes 1188–1190). In contrast, the anti-Gαicommon Ig recognized Gαi1, Gαi2 and Gαi3. The expression levels of Gαi2 and Gαi3 were about tenfold higher than the expression level of Gαi1. Unfortunately, even by testing various virus titers and virus generations, we could not further increase the expression level of Gαi1. (data not shown). Probably, the low expression is an intrinsic property of Gαi1. However, for any given Gαi isoform, expression levels were similar regardless of the co-expression of RGS proteins, allowing for the analysis of the effects of RGS proteins on each Gαi isoform. The 75-kDa band recognized by anti-Gαicommon Ig probably represents a nonspecific band, as it was also recognized in membranes 1178 and 1188–1190. Immunoblots with anti-Gαi1–2 Ig confirmed that Gαi1 was expressed at much lower levels than Gαi2 (Fig. 1d). As expected, anti-Gαi1–2 Ig did not detect Gαi3 (Fig. 1d). Immunoblots with anti-Gαo Ig showed that this G-protein (39 kDa) was properly expressed in Sf9 membranes (Fig. 1e). Anti-Gαo Ig did not detect a 39-kDa band in membrane 1178.

We also estimated the expression level of Gαi2 (and Gαi1) with anti-Gαi1–2 Ig using membranes expressing the β2AR-Gαi2 fusion protein at 3.0 pmol/mg as assessed by [3H]dihydroalprenolol saturation binding as standard (Fig. 2a). The densitometrically determined Gαi2 expression level was ∼150–200 pmol/mg, whereas the expression level of Gαi1 was about tenfold lower. The latter result is in agreement with the data obtained for the anti-Gαicommon Ig (Fig. 1c).

Analysis of the expression of CXCR4, Gα subunits, Gβ subunits, and RGS-proteins in Sf9 membranes. SDS-PAGE and immunoblots were performed as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Unless stated otherwise in (a), 10 μg of membrane protein were loaded onto each lane. Numbers on the left indicate molecular masses (kDa) of marker proteins. Numbers below immunoblots designate the specific membrane studied (see Table 1 for specific protein composition). Shown are the immunoblots of gels containing 12% (m/v) acrylamide. a Anti-Gαi1,2 Ig with β2AR-Gαi2 standard membranes (3.0 pmol/mg as assessed by [3H]dihydroalprenolol saturation binding; 20–250 μg of protein/lane) and representative CXCR4-expressing membranes; b Anti-Gβcommon Ig with CXCR4 membranes; c Anti-hexahistidine Ig with CXCR4 membranes; d Anti-RGS4 Ig with CXCR4 membranes; e Anti-RGS4 plus anti-GAIP Ig with CXCR4 membranes

In the present study (Fig. 1c,e) and in a previous study (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998), we did not obtain evidence for the expression of endogenous Gαi/Gαo-proteins in Sf9 cells. Our data are in contrast to the results obtained by Leopoldt et al. (1997), reporting on the presence of endogenous Gαi/Gαo-proteins in Sf9 cells. There are also discrepancies between our group and Leopoldt et al. (1997) regarding the coupling of the histamine H2-receptor to Gq-proteins (Houston et al. 2002). The reason for these discrepancies is unknown. One possibility that will have to be tested in future studies is that the specific cell culture conditions have an impact on endogenous G-protein expression and receptor/G-protein coupling in Sf9 cells.

The expression of Gβ1 (36 kDa) was confirmed with the anti-Gβcommon Ig (Fig. 2b). As was observed for the expression of CXCR4 (Fig. 1a), the expression of Gβ1 was similar in all membranes studied, regardless of the type of Gα present and the absence or presence of an RGS protein. The anti-Gβcommon Ig did not recognize the endogenous Gβ-like protein of the insect cells (membrane 1178).

Finally, we assessed the expression of RGS proteins. The RGS proteins were N-terminally tagged with a hexahistidine tag, allowing for the simultaneous detection of CXCR4 and RGS proteins with the anti-hexahistidine Ig. We confirmed the migration of CXCR4 as broad glycosylated 37 kDa monomer and 75 kDa dimer (Fig. 2c). RGS4 and GAIP migrated at ∼25 kDa, with GAIP and RGS4 being expressed at somewhat varying levels. RGS4 was specifically detected by the anti-RGS4 Ig (Fig. 1d), and exposure of the nitrocellulose to both anti-RGS4 Ig and anti-GAIP Ig detected both RGS proteins (Fig. 2e).

Collectively, our data show that infection of Sf9 cells with four different baculoviruses encoding for five different mammalian signal transduction proteins is technically feasible, allowing for the systematic analysis of RGS proteins on CXCR4/G-protein coupling. The expression level of human CXCR4 and Gβ1 did not vary with the type of Gα and/or the absence or presence of RGS-proteins. Moreover, there is a large (40- to 50-fold) molar excess of Gαi2 and Gαi3 relative to CXCR4, whereas for Gαi1, the molar excess compared to CXCR4 is just four- to fivefold. Furthermore, RGS4 and GAIP are expressed in Sf9 cells and translocated to the membrane fraction. Thus, although exact expression levels of the various signal transduction proteins cannot be controlled in Sf9 cells, a reasonable comparison of CXCR4 coupling to various Gi/Go-proteins is possible.

Analysis of human CXCR4/G-protein coupling in the steady-state GTPase assay

In the next series of experiments, we compared all 13 membranes side by side in the steady-state GTPase assay (Fig. 3) (Wieland and Seifert 2005), monitoring the outcome of multiple rounds of GDP/GTP exchange catalyzed by human CXCR4. For these studies, we used a SDF-1α concentration of 50 nM. Preliminary studies showed that this concentration of chemokine was sufficient to maximally activate GTP hydrolysis (data not shown). Similarly, SDF-1α at a concentration of 10–100 nM maximally stimulates phospholipase C in COS-7 cells transfected with human CXCR4 (Rosenkilde et al. 2004). In the absence of mammalian G-proteins, SDF-1α only minimally activated GTPase (membrane 1178), indicative of poor coupling of human CXCR4 to endogenous insect cell G-proteins. The human formyl peptide receptors also couples only poorly to insect cell G-proteins (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998).

Comparison of basal and SDF-1α-stimulated GTPase activity in various CXCR4-expressing Sf9 membranes. High-affinity GTPase activity was determined as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Numbers below columns designate the specific membrane studied (see Table 1 for specific protein composition). a Absolute GTPase activities under basal conditions (0.2% (m/v) BSA) or in the presence of a maximally stimulatory concentration of SDF-1α (50 nM). b Relative stimulatory effect of SDF-1α. Data shown are the means ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicates. The statistical significance of the effects of RGS-proteins RGS4 and GAIP versus control on SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis was assessed using the t test. *p < 0.05

In the presence of Gαi1 (membrane 1179), Gαi2 (membrane 1182), and Gαi3 (membrane 1185), robust GTPase stimulations by SDF-1α (80–150%) were observed. In the presence of Gαo (membrane 1188), the GTPase stimulation by SDF-1α was much smaller (20%). The absolute GTPase activities with Gαi3 and Gαo were considerably lower than with Gαi1 and Gαi2. These data show that human CXCR4 couples particularly well to Gαi1 and Gαi2, whereas coupling to Gαi3 and Gαo is less efficient. The efficient GTPase activation in membranes expressing Gαi1 is particularly remarkable in view of the fact that this Gα is expressed at much lower levels than Gαi2 and Gαi3 (Fig. 2) and that Gαi1 is not expressed in cells of the immune systems (Birnbaumer et al. 1990), corroborating the notion that CXCR4 exerts functions beyond leukocytes. Considering the fact that CXCR4 is also expressed in neuronal cells and that Gαo is expressed at high levels in those cells (Birnbaumer et al. 1990; Bajetto et al. 2001; Guyon and Nahon 2007), the inefficient GTPase activation by SDF-1α in Gαo-expressing Sf9 membranes suggests that in vivo, CXCR4 predominantly operates through Gi- rather than Go-linked signal transduction pathways.

Previous studies showed that RGS-proteins can enhance GPCR agonist-stimulated steady-state GTP hydrolysis, improving the signal-to-noise ratio of test systems (Houston et al. 2002; Ward and Milligan 2004). Because the main aim of this study was to establish a sensitive CXCR4 expression system allowing for the analysis of partial agonists/antagonists and inverse agonists, we also examined the effect of RGS-proteins on steady-state GTP hydrolysis catalyzed by CXCR4 with the various G-proteins. As is shown in Fig. 2c, the expression of RGS4 and GAIP exhibited some variability in the various membranes. Despite this variability, both RGS proteins enhanced SDF-1α-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis in all Gαi- and Gαo-expressing membranes significantly, i.e., by about 50% (Fig. 3). As a result of the enhancement, the membranes with the highest signal-to-noise ratios were those expressing Gαi2 along with RGS4 or GAIP, yielding GTPase stimulations of >3.5-fold (Fig. 3b). Thus, for future pharmacological studies, a very sensitive test system for human CXCR4 ligands is available.

Because the N-terminus of CXCR4 is involved in the initial binding of the agonist SDF-1α (Gerlach et al. 2001; Gupta et al. 2001) and because introduction of an N-terminal hemagglutinin epitope in a mouse CXCR4 isoform is detrimental for its function (Moepps et al. 1997), we were concerned that the N-terminal FLAG epitope modification may impede with the interaction of SDF-1α and human CXCR4 as well. To address this issue, we analyzed concentration–response curves of SDF-1α for GTPase activation. In membranes expressing Gαi2, the EC50 of SDF-1α amounted to 1.2 ± 0.4 nM (Fig. 4a) which is in good agreement with the potency of SDF-1α in other test systems for human CXCR4 (Gupta et al. 2001; Gerlach et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2002; Rosenkilde et al. 2004). This result also indicates that the N-terminal FLAG epitope modification does not interfere with agonist recognition at human CXCR4. The reason why N-terminal epitope modification interferes with the function of some but not all CXCR4 isoforms is unknown. However, from the practical point of view, one has to be aware of the fact that unlike for other peptide GPCRs (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998; Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001), chemokine receptor function is very sensitive to epitope-tagging.

Concentration/response curves for the effects of SDF-1α and AMD3100 on GTPase activity in Sf9 membranes expressing CXCR4. High-affinity GTPase activity was determined as described in the “Materials and methods” section in Sf9 membrane 1182 (CXCR4 + Gαi2 + Gβ1γ2). a Effects of SDF-1α and AMD3100 on basal GTPase activity. b Inhibitory effect of AMD3100 on GTPase activity stimulated by SDF-1α (10 nM). Data shown are the means ± SD of a representative experiment performed in triplicates. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments with different membrane preparations

The potencies of agonists may depend on the specific Gα subtype to which a GPCR is coupled (Wenzel-Seifert and Seifert 2000). Therefore, we also determined the potencies of SDF-1α with Gαi1, Gαi3 and Gαo. However, the fact that in all systems, the EC50 for SDF-1α ranged just between 1–3 nM (data not shown) indicates that for this GPCR, the type of Gα coupling partner is not critical for agonist potency. In agreement with the present data for CXCR4, the potency of agonists at activating the formyl peptide receptor is similar when coupled to Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1999). Figure 4a also shows that the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 exhibited no stimulatory or inhibitory effect on basal GTP hydrolysis, indicating that this compound is neither a partial agonist nor an inverse agonist but a true neutral antagonist (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2002). At a constitutively active CXCR4 mutant AMD3100 is a weak partial agonist (Zhang et al. 2002). The antagonistic properties of AMD3100 at wild-type human CXCR4 are documented in Fig. 4b. Specifically, AMD3100 inhibited SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis with an apparent K i value of 47 ± 8 nM which is in good agreement with the literature (Gerlach et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2002). Again, these data corroborate the notion that the pharmacological properties of human CXCR4 are not altered by the N-terminal FLAG epitope. The apparent discrepancy between the calculated K i value according to Cheng and Prusoff (1973) and the IC50 value shown in Fig. 4b (440 nM) is because of the fact that we used a SDF-1a concentration of 10 nM which is about eightfold above the EC50 value for SDF-1α (Fig. 4a). We also noted that with AMD3100 at a concentration of 10 μM, we could not fully reduce GTPase activity to the basal values observed in Fig. 4a. However, due to the limited solubility of this compound, we could not use higher concentrations in our assay.

It is well established that Na+ acts as an allosteric inverse agonist at several Gi/Go-coupled GPCRs and stabilizes the inactive (R) state of the receptors (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001, 2002). Accordingly, Na+ is very efficient at reducing the basal GTPase activity in systems expressing GPCRs with high constitutive activity, reflecting the high agonist-independent GDP/GTP turnover (Gierschik et al. 1989; Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998). In contrast, in systems with low constitutive activity, Na+ does not decrease basal GTPase activity (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001). It is also well known that other monovalent cations such as K+ and Li+ are less efficient than Na+ at stabilizing the R state of constitutively active GPCRs (Gierschik et al. 1989; Costa et al. 1990; Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998). As is shown in Fig. 5a,e,h, Na+ exhibited only a very small inhibitory effect on basal GTPase activity in Sf9 membranes expressing human CXCR4 and Gαi2, regardless of the halide counter anion (Cl−, Br−, or I−) used. Because Na+ is a universal allosteric stabilizer of the R state of Gi-linked GPCRs (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001), our data indicate that human wild-type CXCR4 is essentially devoid of constitutive activity. Consistent with this notion is the fact that certain point mutations result in the generation of constitutively active CXCR4 mutants (Zhang et al. 2002).

Concentration/response curves for the effects of various monovalent salts on basal and SDF-1α-stimulated GTPase activity in Sf9 membranes expressing CXCR4. High-affinity GTPase activity was determined as described in the “Materials and methods” section in Sf9 membrane 1182 (CXCR4 + Gαi2 + Gβ1γ2). Reaction mixtures contained either 0.2% (m/v) BSA (basal) or 50 nM SDF-1α. In addition, reaction mixtures contained monovalent salts at the concentrations indicated on the abscissa. a LiCl; b NaCl; c KCl; d LiBr; e NaBr; f KBr; g LiI; h NaI; i KI. Data shown are the means ± SD of a representative experiment performed in triplicates. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments with different membrane preparations

The experiments shown in Fig. 5 were performed with SDF-1α at a concentration of 50 nM, which was sufficient for maximal GTPase stimulation in the absence of added monovalent salts (Fig. 4a). However, we noticed that, despite the lack of inhibitory effects of monovalent salts on basal GTPase activity, they nonetheless reduced the maximum extent of agonist-stimulated GTP hydrolysis in a concentration-dependent manner. Surprisingly, the inhibitory effect of monovalent salts on agonist-stimulated GTP hydrolysis strongly depended on the type of anion. Particularly, the order of potency and efficacy of anions at reducing SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis was I− > Br− > Cl− (Fig. 5), i.e., the order depended on the anion radius. Figure 6 shows that monovalent salts did not only reduce the efficacy of SDF-1α at activating GTP hydrolysis but also its potency. Specifically, with 150 mM LiCl, NaCl and KCl, the potency of SDF-1α was reduced by 22-fold, 26-fold, and 32-fold, respectively.

Concentration/response curves for the effects of SDF-1α on GTPase activity in Sf9 membranes expressing CXCR4 in the presence of various monovalent salts. High-affinity GTPase activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods in Sf9 membrane 1182 (CXCR4 + Gαi2 + Gβ1γ2). Reaction mixtures contained SDF-1α at various concentrations in the absence and presence of monovalent salts at various fixed concentrations (50 mM, 100 mM or 150 mM). a, effect of LiCl; b, effect of NaCl; c, effect of KCl. Data shown are the means ± SD of a representative experiment performed in triplicates. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments with different membrane preparations

Our data on anion effects on SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis are reminiscent of previous observations made for the β2AR coupled to the long splice variant of Gαs. In this system, anions reduced the efficacy of the agonist isoproterenol at activating adenylyl cyclase in the order I− > Br− > Cl− (Seifert 2001). Those data were explained by a model in which halides increase the GDP-affinity of Gαs (Seifert 2001). In accordance with this model, Cl− anions decrease GDP dissociation from purified Gαo (Higashijima et al. 1987). By analogy, halides could increase the GDP-affinity of Gαi2, thereby rendering agonist-stimulated GDP/GTP exchange less efficient (Seifert 2001). Alternatively, halides may impair the ionic interaction of the positively charged binding site in SDF-1α with its negatively charged binding grove in CXCR4 (Zhou and Tai 2000).

However, if anions impair ionic SDF-1α/hCXCR4 interaction, the same should be true for cations. In fact, monovalent cations do have an impact on SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis as well. Specifically, with NaCl, KCl, NaBr, and KBr, biphasic concentration/response curves were observed, i.e., salts at concentrations <50 mM even enhanced SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis, and higher concentrations were inhibitory (Fig. 5b,c,e and f). In contrast, LiCl and LiBr did not show those biphasic properties (Fig. 5a and d). Moreover, KI was more effective at suppressing SDF-1α-stimulated GTP hydrolysis than LiI and NaI (Fig. 5g–i).

Regardless of the specific mechanism(s) involved, from a technical perspective, the substantial impact of monovalent salts on CXCR4-mediated G-protein activation should be considered in future experiments. It is unknown whether there is any physiological relevance of the regulation of CXCR4/SDF-1α interaction by monovalent anions and cations, but it is possible that changes in extracellular Na+ and/or Cl− concentrations in pathophysiological conditions such as inflammatory edema could affect the potency of SDF-1α at activating CXCR4. Br− and I− are of no physiological relevance and constitute only pharmacological tools.

Analysis of human CXCR4/G-protein coupling in the GTPγS binding assay

Whereas the GTPase assay assesses steady-state GDP/GTP turnover of G-proteins, the GTPγS binding assay monitors the kinetics of G-protein activation and the stoichiometry of GPCR/G-protein interaction (Gierschik et al. 1991; Seifert et al. 1998; Wenzel-Seifert and Seifert 2000; Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1998, 1999). SDF-1α activated GTPγS binding to Gαi2 with a t 1/2 of 34.8 ± 6.8 min, and RGS4 had no effect on the GTPγS binding kinetics (t 1/2 of 34.8 ± 5.8 min; Fig. 7a and b). Thus, the Gαi2 activation kinetics of CXCR4 is considerably slower than those of chemoattractant receptors for formyl peptides, complement C5a, platelet-activating factor, and leukotriene B4 (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001). These data point to different (patho)physiological functions of CXCR4 relative to chemoattractant receptors. Possibly, the slow Gαi2 activation kinetics of CXCR4 reflect its role in the long-term regulation of homeostatic functions, i.e., tissue development and differentiation as well as endothelial progenitor and T-cell mobilization (Moepps et al. 2000; Bajetto et al. 2001; Buckingham 2006; Hristov et al. 2007).

Regulation of GTPγS binding by SDF-1α in Sf9 membranes expressing CXCR4. GTPγS binding was determined as described in the “Materials and methods” section in Sf9 membrane 1182 (CXCR4 + Gαi2 + Gβ1γ2) and 1183 (CXCR4 + Gαi2 + Gβ1γ2 + RGS4). a and b Time course of GTPγS binding. Reaction mixtures contained 1 μM GDP plus 0.4 nM [35S]GTPγS and 15 μg of membrane 1182 (a) or 1183 (b). Reactions were conducted for the periods of time indicated on the abscissa. Basal GTPγS binding was subtracted from GTPγS binding in the presence of SDF-1α. Thus, SDF-1α-stimulated GTPγS binding is shown. c and d GTPγS saturation binding. Reaction mixtures contained 1 μM GDP plus 0.2–20 nM [35S]GTPγS as indicated on the abscissa and 15 μg of membrane 1182 (c) or 1183 (d). Reactions were conducted for 90 min. Basal GTPγS binding was subtracted from SDF-1α-stimulated GTPγS binding. Thus, SDF-1α-stimulated GTPγS binding is shown. Data shown are the means ± SD of three independent experiments performed in duplicates. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments with different membrane preparations

The K d of SDF-1α-stimulated GTPγS binding was 2.8 ± 0.7 nM, and RGS4 had no effect on K d (2.8 ± 0.3 nM; Fig. 7c and d). The K d value of agonist-stimulated GTPγS binding for CXCR4 is higher than the K d value for most chemoattractant receptors (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001), further corroborating the notion of different functions of CXCR4 compared to chemoattractant receptors. The B max value of SDF-1α-stimulated GTPγS value was 5.3 ± 0.4 pmol/mg, and again, RGS4 had no major effect (6.5 ± 0.2 pmol/mg; Fig. 7c and d).

The densitometrically determined Bmax of human CXCR4 was ∼4 pmol/mg (Fig. 1b), and there is a large molar excess of Gαi2 relative to CXCR4 in Sf9 membranes (Figs. 1 and 2). Thus, the concentration of Gαi2 should be sufficiently high to ensure coupling of most if not all CXCR4 molecules to Gi-proteins. Assuming that all expressed CXCR4 molecules are also folded correctly and functionally active, one CXCR4 molecule activated ∼1.0–1.5 Gαi2 molecules, i.e., in the Sf9 cell system, signal transfer would be linear or almost linear. Linear G-protein activation has also been found for chemoattractant receptors expressed in Sf9 cells (Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1999; Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert 2001). However, in a native cell system, i.e., membranes from differentiated HL-60 leukemia cells, signal transfer between the formyl peptide receptor and Gi-proteins is catalytic (Gierschik et al. 1991), clearly showing that the stoichiometry of signal transfer between receptors and G-proteins is system-dependent.

The lack of effect of RGS4 on GTPγS binding (Fig. 7) is expected (Ross and Wilkie 2000) and contrasts to the prominent stimulatory effect of these regulatory proteins on steady-state GTP hydrolysis (Fig. 3). The stimulatory effect of RGS proteins on agonist-stimulated steady-state GTP hydrolysis shows that under these conditions, GTP hydrolysis becomes the rate-limiting step of the G-protein cycle (Ross and Wilkie 2000; Houston et al. 2002; Ward and Milligan 2004).

Conclusions

In the present study, we have reconstituted the human CXCR4 with various Gi/Go-proteins in Sf9 insect cells. The high-affinity GTPase assay provides an excellent signal-to-noise ratio and constitutes a suitable test system for future pharmacological analysis of CXCR4. Specifically, the system can be used for the characterization of CXCR4 antagonists that are of potential value for the treatment of autoimmune diseases and tumors (Kucia et al. 2004; Tamamura et al. 2006; Kryczek et al. 2007). An advantage of the GTPase assay is that it assesses receptor/G-protein coupling at a proximal level and steady-state conditions and allows for pharmacological analysis without bias introduced by potential nonlinearity of downstream signaling (Wieland and Seifert 2005; Seifert et al. 1998). Agonist-stimulation of GTPase is very sensitive to monovalent anions; either due to increases in G-protein GDP-affinity or interference with ligand/receptor interaction. Monovalent cations modulate CXCR4-mediated signal transduction as well, although to a lesser extent than anions. The enhancing effects of RGS-proteins on steady-state GTPase activity indicates that GTP hydrolysis becomes rate-limiting under conditions of agonist-stimulation (Ross and Wilkie 2000).

Human CXCR4 does not exhibit constitutive activity. The lack of constitutive activity points to tight ligand-regulated control of CXR4 function. Given the crucial role of CXCR4 in the regulation of so many homeostatic functions, lack of constitutive CXCR4 activity may be essential to avoid deleterious effects for the organism. In Sf9 cells, CXCR4 couples differentially to Gi/Go-proteins with preference for Gαi1 and Gαi2. The possible physiological relevance of the differential CXCR4 coupling to Gi/Go-proteins should be assessed in native cell systems using the [α-32P]GTP azidoanilide labelling technique (Offermanns et al. 1991).

A limitation of the Sf9 co-expression system is the fact that the expression levels of Gi/Go-proteins and RGS-proteins cannot be precisely controlled. A solution to this problem could be the construction, expression, and functional analysis of CXCR4-Gα- and CXCR4-RGS fusion proteins (Seifert et al. 1998; Wenzel-Seifert et al. 1999; Wenzel-Seifert and Seifert 2000; Ward and Milligan 2004). Finally, although the N- and C-terminal epitope tags of CXCR4 used in the present study are very useful in terms of immunological detection of the receptor and apparently without gross effect on receptor function, it should be kept in mind that N-terminal epitopes can affect agonist binding to certain chemokine receptors including defined CXCR4 isoforms and, thereby, impair CXCR4/G-protein coupling (Moepps et al. 1997).

Abbreviations

- AMD3100:

-

1-[[1,4,8,11-tetrazacyclotetradec-1-ylmethyl)phenyl]methyl]-1,4,8,11-tetrazacyclotetradecane

- BSA:

-

bovine serum albumin

- β2AR:

-

β2-adrenoceptor

- GPCR:

-

G-protein-coupled receptor

- GTPγS:

-

guanosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate

- GAIP:

-

Gα-interacting protein

- RGS protein:

-

Regulator of G-protein Signalling protein

- SDF-1α:

-

stromal cell-derived factor-1α

- Sf9 cells:

-

Spodoptera frugiperda pupal ovary cells

References

Bajetto A, Bonavia R, Barbero S, Florio T, Schettini G (2001) Chemokines and their receptors in the central nervous system. Front Neuroendocrinol 22:147–184

Birnbaumer L (2007) Expansion of signal transduction by G proteins. The second 15 years or so: from 3 to 16 α subunits plus βγ dimers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768:772–793

Birnbaumer L, Abramowitz J, Brown AM (1990) Receptor–effector coupling by G proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1031:163–224

Buckingham M (2006) Myogenic progenitor cells and skeletal myogenesis in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev 16:525–532

Chen W-J, Jayawickreme C, Watson C, Wolfe L, Holmes W, Ferris R, Armour S, Dallas W, Chen G, Boone L, Luther M, Kenakin T (1998) Recombinant human CXC-chemokine receptor-4 in melanophores are linked to Gi protein: Seven transmembrane coreceptors for human immunodeficiency virus entry into cells. Mol Pharmacol 53:177–181

Cheng Y, Prusoff WH (1973) Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol 22:3099–3108

Costa T, Lang J, Gless C, Herz A (1990) Spontaneous association between opioid receptors and GTP-binding regulatory proteins in native membranes: specific regulation by antagonists and sodium ions. Mol Pharmacol 37:383–394

Ganju RK, Brubaker SA, Meyer J, Dtt P, Yang Y, Qin S, Newman W, Groopman JE (1998) The α-chemokine, stromal cell-derived factor-1α, binds to the transmembrane G-protein-coupled CXCR-4 receptor and activates multiple signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem 273:23169–23175

Gerlach LO, Skerlj RT, Bridger GJ, Schwartz TW (2001) Molecular interactions of cyclam and bicyclam non-peptide antagonists with the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem 276:14153–14160

Gierschik P, Sidiropoulos D, Steisslinger M, Jakobs KH (1989) Na+ regulation of formyl peptide receptor-mediated signal transduction in HL 60 cells. Evidence that the cation prevents activation of the G-protein by unoccupied receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 172:481–492

Gierschik P, Moghtader R, Straub C, Dietrich K, Jakobs KH (1991) Signal amplification in HL-60 granulocytes. Evidence that the chemotactic peptide receptor catalytically activates guanine-nucleotide-binding regulatory proteins in native plasma membranes. Eur J Biochem 197:725–732

Graber SG, Figler RA, Garrison JC (1992) Expression and purification of functional G protein α subunits using a baculovirus expression system. J Biol Chem 267:1271–1278

Gupta SK, Pillarisetti K, Thomas RA, Aiyar N (2001) Pharmacological evidence for complex and multiple site interaction of CXCR4 with SDF-1α: implications for development of selective CXCR4 antagonists. Immunol Lett 78:29–34

Guyon A, Nahon JL (2007) Multiple actions of the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1α on neuronal activity. J Mol Endocrinol 38:365–376

Higashijima T, Ferguson KM, Sternweis PC (1987) Regulation of hormone-sensitive GTP-dependent regulatory proteins by chloride. J Biol Chem 262:3597–3602

Houston C, Wenzel-Seifert K, Bürckstümmer T, Seifert R (2002) The human histamine H2-receptor couples more efficiently to Sf9 insect cell Gs-proteins than to insect cell Gq-proteins: limitations of Sf9 cells for the analysis of receptor/Gq-protein coupling. J Neurochem 80:678–696

Hristov M, Zernecke A, Liehn EA, Weber C (2007) Regulation of endothelial progenitor cell homing after arterial injury. Throm Haemost 98:274–277

Jones DT, Reed RR (1987) Molecular cloning of five GTP-binding protein cDNA species from rat olfactory neuroepithelium. J Biol Chem 262:14241–14249

Kryczek I, Wei S, Keller E, Liu R, Zou W (2007) Stroma-derived factor (SDF-1/CXCL12) and human tumor pathogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292:C987–C995

Kucia M, Jankowski K, Reca R, Wysoczynski M, Bandura L, Allendorf DJ, Zhang J, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ (2004) CXCR4-SDF1 signalling, locomotion, chemotaxis and adhesion. J Mol Histol 35:233–245

Leopoldt D, Harteneck C, Nürnberg B (1997) G proteins expressed in Sf 9 cells: interactions with mammalian histamine receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol 356:216–224

Moepps B, Frodl R, Rodewald HR, Baggiolini M, Gierschik P (1997) Two murine homologues of the human chemokine receptor CXCR4 mediating stromal cell-derived factor 1α activation of Gi2 are differentially expressed in vivo. Eur J Immunol 27:2102–2112

Moepps B, Braun M, Knöpfle K, Dillinger K, Knöchel W, Gierschik P (2000) Characterization of a Xenopus laevis CXC chemokine receptor 4: implications for hematopoietic cell development in the vertebrate embryo. Eur J Immunol 30:2924–2934

Murphy PM (2002) International Union of Pharmacology. XXX. Update on chemokine receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev 54:227–229

Ödemis V, Moepps B, Gierschik P, Engele J (2002) Interleukin-6 and cAMP induce stromal cell-derived factor-1 chemotaxis in astroglia by up-regulating CXCR4 cell surface expression. J Biol Chem 277:39801–39808

Offermanns S, Schultz G, Rosenthal W (1991) Identification of receptor-activated G proteins with photoreactive GTP analog, [α-32P]GTP azidoanilide. Methods Enzymol 195:286–301

Percherancier Y, Berchiche YA, Slight I, Volkmer-Engert R, Tamamura H, Fujii N, Bouvier M, Heveker N (2005) Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer reveals ligand-induced conformational changes in CXCR4 homo- and heterodimers. J Biol Chem 280:9895–9903

Rosenkilde MM, Gerlach LO, Jakobsen JS, Skerlj RT, Bridger GJ, Schwartz TW (2004) Molecular mechanism of AMD3100 antagonism in the CXCR4 receptor. Transfer of binding site to the CXCR3 receptor. J Biol Chem 279:3033–3041

Ross EM, Wilkie TM (2000) GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signalling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 69:795–827

Seifert R (2001) Monovalent anions differentially modulate coupling of the β2-adrenoceptor to Gsα splice variants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298:840–847

Seifert R, Wenzel-Seifert K (2001) Unmasking different constitutive activity of four chemoattractant receptors using Na+ as universal stabilizer of the inactive (R) state. Receptors Channels 7:357–369

Seifert R, Wenzel-Seifert K (2002) Constitutive activity of G-protein-coupled receptors: cause of disease and common properties of wild-type receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol 366:381–416

Seifert R, Lee TW, Lam VT, Kobilka BK (1998) Reconstitution of β2-adrenoceptor-GTP-binding-protein interaction in Sf9 cells—high coupling efficiency in a β2-adrenoceptor-Gsα fusion protein. Eur J Biochem 255:369–382

Tamamura H, Tsutsumi H, Fujii N (2006) The chemokine receptor CXCR4 as a therapeutic target for several diseases. Mini Rev Med Chem 6:989–995

Tsibris AM, Kuritzkes DR (2007) Chemokine antagonists as therapeutics. Focus on HIV. Annu Rev Med 58:445–459

Walseth TF, Johnson RA (1979) The enzymatic preparation of [α-32P] nucleoside triphosphates, cyclic [32P] AMP, and cyclic [32P] GMP. Biochim Biophys Acta 562:11–31

Ward RJ, Milligan G (2004) Analysis of function of receptor-G-protein and receptor-RGS fusion proteins. Methods Mol Biol 259:225–247

Wenzel-Seifert K, Seifert R (2000) Molecular analysis of β2-adrenoceptor coupling to Gs-, Gi-, and Gq-proteins. Mol Pharmacol 58:954–966

Wenzel-Seifert K, Hurt CM, Seifert R (1998) High constitutive activity of the human formyl peptide receptor. J Biol Chem 273:24181–24189

Wenzel-Seifert K, Arthur JM, Liu HY, Seifert R (1999) Quantitative analysis of formyl peptide receptor coupling to Giα1, Giα2, and Giα3. J Biol Chem 274:33259–32566

Wieland T, Seifert R (2005) Methodological Approaches. In: Seifert R, Wieland T (eds) G-protein-coupled receptors as drug targets (Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry). Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, pp 81–120

Zhang WB, Navenot JM, Haribabu B, Tamamura H, Hiramatu K, Omagari A, Pei G, Manfredi JP, Fujii N, Broach JR, Peiper SC (2002) A point mutation that confers constitutive activity to CXCR4 reveals that T140 is an inverse agonist and that AMD3100 and ALX40-4C are weak partial agonists. J Biol Chem 277:24515–24521

Zhou H, Tai HH (1999) Characterization of recombinant human CXCR4 in insect cells: role of extracellular domains and N-glycosylation in ligand binding. Arch Biochem Biophys 369:267–276

Zhou H, Tai HH (2000) Expression and functional characterization of mutant human CXCR4 in insect cells: role of cysteinyl and negatively charged residues in ligand binding. Arch Biochem Biophys 373:211–217

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Erich Schneider for stimulating discussions as well as Mrs. Astrid Seefeld and Gertraud Wilberg for expert technical assistance. Thanks are also due to the reviewers of the paper for their constructive critique and suggestions.

This work was supported by the Research Training Program (Graduiertenkolleg) GRK 760 “Medicinal Chemistry: Molecular Recognition—Ligand–Receptor Interactions” of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the “International Study and Training Partnerships (ISAP) Program” of the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst and by the National Institutes of Health COBRE Award 1 P20 RR15563 and matching support from the State of Kansas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Patrick Kleemann and Dan Papa contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleemann, P., Papa, D., Vigil-Cruz, S. et al. Functional reconstitution of the human chemokine receptor CXCR4 with Gi/Go-proteins in Sf9 insect cells. Naunyn-Schmied Arch Pharmacol 378, 261–274 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-008-0313-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-008-0313-8