Abstract

The Asia -Pacific Bone Academy (APBA) Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) Focus Group educational initiative has stimulated activity across the Asia -Pacific region with the intention of supporting widespread implementation of new FLS. In 2017, the APBA FLS Focus Group developed a suite of tools to support implementation of FLS across the Asia-Pacific region as a component of a multi-faceted educational initiative. This article puts this initiative into context with a narrative review describing the burden of fragility fractures in the region, the current secondary fracture prevention care gap and a summary of emerging best practice. The results of a survey to evaluate the impact of the APBA educational initiative is presented, in addition to commentary on recent activities intended to improve the care of individuals who sustain fragility fractures across the Asia -Pacific. A FLS Toolbox for Asia-Pacific was developed which included the following sections:

1. The burden of fragility fractures in the Asia-Pacific region.

2. A summary of evidence for FLS in the Asia-Pacific.

3. A generic, fully referenced FLS business plan template.

4. Potential cost savings accrued by each country, based on a country-specific FLS Benefits Calculator.

5. How to start and expand FLS programmes in the Asia-Pacific context.

6. A step-by-step guide to setting up FLS in countries in the Asia-Pacific region.

7. Other practical tools to support FLS establishment.

8. FLS online resources and publications.

The FLS Toolbox was provided as a resource to support FLS workshops immediately following the 5th Scientific Meeting of the Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies (AFOS) held in Kuala Lumpur in October 2017. The FLS workshops addressed three key themes:

• The FLS business case.

• Planning the FLS patient pathway.

• The role of the FLS coordinator in fragility fracture care management.

A follow-up survey of 142 FLS workshop participants was conducted in August–September 2018. The survey included questions regarding how FLS were developed, funded, the scope of service provision and the support provided by the educational initiative. Almost one-third (30.3%) of FLS workshop participants completed the survey. Survey responses were reported for those who had established a FLS at the time the survey was conducted and, separately, for those who had not established a FLS. Findings for those who had established a FLS included:

• 78.3% of respondents established a multidisciplinary team to develop the business case for their FLS.

• 87.0% of respondents stated that a multidisciplinary team was established to design the patient pathway for their FLS.

• 26.1% of respondents stated that their FLS has sustainable funding.

• The primary source of funding for FLS was from public hospitals (83.3%) as compared with private hospitals (16.7%).

Most hospitals that had not established a FLS at the time the survey was conducted were either in the process of setting-up a FLS (47%) or had plans in place to establish a FLS for which approval is being sought (29%). The primary barrier to establishing a new FLS was lack of sustainable funding. The APBA FLS Focus Group educational initiative has stimulated activity across the Asia-Pacific region with the intention of supporting widespread implementation of new FLS. A second edition of the FLS Toolbox is in development which is intended to complement ongoing efforts throughout the region to expedite widespread implementation of FLS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The ageing population in Asia Pacific

In 2017, the United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs reported the global population to be 7.6 billion people [1]. In total, 4.5 billion live in Asia, representing 60% of the world’s inhabitants. China and India continue to be the most populous countries with populations of 1.4 billion and 1.3 billion, respectively. Globally, the proportion of older people aged ≥ 60 years (13%) is half that of children aged < 15 years (26%), a situation which is set to change dramatically in the coming decades. The combination of declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy will continue to fuel ageing of the population worldwide. As illustrated in Fig. 1, as compared with the beginning of the century, the number of people aged ≥ 65 years in Asia will more than quadruple by 2050 and increase by almost sixfold by 2100 [2].

People aged 65 years or over in Asia Pacific during the period 2000–2100 [2]. From World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Volume I: Comprehensive Tables (ST/ESA/SER.A/399), by Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, ©2017 United Nations. Reprinted with the permission of the United Nations

A demographic shift on this scale and at this unprecedented rate will have major implications for the economies of nations throughout the region. Age-dependency ratios provide a crude measure of individuals who are more likely to be active in the work force (i.e. those aged 15 to 64 years) as compared with those who typically are not (i.e. children aged 0 to 14 years and adults aged 65 years or over). The so-called “old-age” dependency ratio is the ratio of the population aged ≥ 65 years to the population aged 15–64 years, who are considered to be of “working age”. These ratios are presented as number of dependents per 100 persons of working age. In Asia, the UN analyses and projections suggest that the ratio increased from 6.8 older persons per 100 working age persons in 1950 to a ratio of 11.2:100 in 2015 [3]. As illustrated in Fig. 2, Asia is currently passing through a point of inflection whereby ratios are projected increase to 17.5:100, 27.8:100 and 46.3:100 by 2030, 2050 and 2100, respectively. While the analogous child dependency ratio in the region declined from 61.1:100 in 1950 to 36.2:100 in 2015, and is projected to decline further to 26.1:100 by 2100, the total dependency ratio (i.e. the number of children aged < 15 years combined with adults aged > 64 years, as compared with people of working age) will have increased from 47.3:100 in 2015 to 55.8:100 in 2050 and 72.4:100 in 2100. Notably, these trends are evident in countries categorised by the UN as high income (New Zealand), upper-middle income (China), lower-middle income (Philippines) and low income (North Korea).

Old-age dependency ratios for Asia Pacific countries from 1950 to 2100 [3]. From World Population Prospects: Volume II: Demographic Profiles 2017 Revision. ST/ESA/SER.A/400, by Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, ©2017 United Nations. Reprinted with the permission of the United Nations.

A direct consequence of this “longevity miracle”—if left unchecked—will be an explosion in the incidence of chronic diseases afflicting older people. To paraphrase Ebeling [4], “Osteoporosis, falls and the fragility fractures that follow will be at the vanguard of this battle which is set to rage between quantity and quality of life.”

The burden of osteoporosis in Asia Pacific

The group of countries which constitute the Asia Pacific region is defined differently by major global organisations. The UN considers Asia to be comprised of 48 countries (where mainland China, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region [SAR], Macao SAR and Taiwan are considered collectively to be one country). This includes 5 countries designated as Eastern Asia, 14 countries as South-Central Asia, 11 countries as South-Eastern Asia and 18 countries as Western Asia [2]. The UN also considers Oceania to comprise 23 countries, thus a total of 71 countries in Asia Pacific, from Samoa in the East to Turkey in the West. The World Bank operates in regions designated as East Asia and Pacific, South Asia and Europe and Central Asia, comprising 15, 8 and 9 countries in Asia Pacific, respectively [5].

In 2018, the Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies (AFOS) published an update to hip fracture projections for the following countries/regions in Asia: China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand [6]. The AFOS investigators estimated the total population of these countries/regions in 2018 to be 3.1 billion, accounting for 70% and 42% of the Asian and global populations, respectively. For 2018 and 2050, the projected numbers of hip fractures and direct cost of hip fractures are shown in Fig. 3a, b, respectively. In 2018, more than 1.1 million hip fractures were anticipated to occur in the nine countries/regions incurring an estimated direct cost of US$7.4 billion. By 2050, the number of hip fractures will increase by 2.3-fold to more than 2.5 million cases per year, resulting in projected costs of almost US$13 billion. Notably, China sustained 43.1% of the hip fractures in 2018, but incurred just 22.7% of the costs across the region, while Japan sustained 15.9% of the hip fractures, but incurred 66.4% of the costs. However, the cost estimates for China may be conservative because they are based on the direct cost for each hip fracture being US$3486. A recent multi-centre study from Zhang et al. estimated hospitalisation costs for hip fracture using data from the Chinese National Medical Data Centre database [7]. The hospitalisation cost for hip fracture in China in 2014 values was estimated to be US$8,550 (¥53 440), which would place the current burden at US$4.1 billion.

During the last decade, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) has undertaken regional audits for Asia Pacific [8], Eastern Europe and Central Asia [9] and Middle East and Africa [10]. More recently, IOF published the IOF Compendium of Osteoporosis, which summarises the findings of the regional audits and, where available, more recent epidemiological studies [11]. Table 1 provides a summary of annual hip fracture incidence and direct costs associated with hip fractures for the countries considered by the UN to be in the Asia and Oceania regions which were not included in the AFOS study [6], where data are available from the IOF reports [8,9,10,11] or more recent studies and analyses based on UN population estimates [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Annual hip fracture incidence is known for approximately half of the countries (12/26) and estimates of the direct cost of hip fractures are available for almost 70% (18/26) of the countries. All the IOF Regional Audits highlight the absence of robust epidemiological data for many countries, and the need for epidemiological research to be undertaken to enable the burden of disease to be accurately quantified in all countries.

The rationale for secondary fracture prevention

In light of the scale of the burden that fragility fractures caused by osteoporosis impose on the population of the Asia Pacific region (and the world), healthcare professionals, policymakers and other stakeholders may reasonably pose the question, where does one start to tackle such an enormous challenge? The IOF World Osteoporosis Day thematic report [21], which launched the IOF Capture the Fracture® Programme [22], proposed a pragmatic answer to this question:

Nature has provided us with an opportunity to systematically identify a significant proportion of individuals that will suffer fragility fractures in the future. This is attributable to the well-recognised phenomenon that fracture begets fracture. Those patients that suffer a fragility fracture today are much more likely to suffer fractures in the future; in fact, they are twice as likely to fracture as their peers that haven’t fractured yet. From the obverse view, we have known for three decades that almost half of patients presenting with hip fractures have previously broken another bone.

Science has provided us with a broad spectrum of effective pharmacological agents to reduce the risk of future fractures. These medicines have been shown to reduce fracture rates amongst individuals with and without fracture history, and even amongst those that have already suffered multiple fractures.

Individuals who have sustained a first fragility fracture are at considerably increased risk of sustaining subsequent fractures. Meta-analyses have established that a history of fracture at any skeletal site is associated with approximately a doubling of future fracture risk [23, 24]. Further, subsequent fractures appear to occur rapidly after an index fracture. In 2004, Swedish investigators examined the pattern of fracture risk following a prior fracture at the spine, shoulder or hip [25]. During 5 years of follow-up, one-third of all subsequent fractures occurred within the first year after fracture, and less than 9% of all subsequent fractures occurred in the fifth year.

Several studies have noted that up to half of hip fracture patients sustained fractures at other skeletal sites during the months and years before breaking their hip. This was first reported by US investigators in 1980 [26], and has more recently been reported in studies from Australia [27], Scotland [28] and the USA [29]. In this regard, the Australian group coined the term “signal fracture” to highlight the opportunity presented when individuals seek medical attention at a hospital or community-based fracture clinic.

The evidence base for secondary fracture prevention and clinical guidance

In 2016, Harvey et al. summarised the evidence base for pharmacological treatments specifically in the context of secondary fracture prevention [30]. The relative risk reductions (RRR) observed for hip fracture and vertebral fracture were in the range 25–50% and 30–65%, respectively, varying according to the agent used and the characteristics of the populations treated. The RRRs for non-vertebral fracture varied from 20 to 53%.

Numerous clinical practice guidelines throughout the world identify individuals who have sustained fragility fractures as a readily identifiable high-risk group that should be targeted for bone health assessment and the risk of falling. In this regard, the well-known National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK has published the following comprehensive suite of technology appraisals, clinical guidelines and quality standards relating to management of fragility fractures:

NICE technology appraisals (TA):

NICE TA 464 (update): Bisphosphonates for treating osteoporosis (updated February 2018) [31].

NICE TA 161 (update): Raloxifene and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women (updated February 2018) [32].

NICE TA 204: Denosumab for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women [33].

NICE clinical guidelines (CG):

NICE quality standards (QS):

Clinical guidelines on the management of osteoporosis are available in many countries/regions in Asia Pacific, including Australia [38], China [39], Hong Kong [40], India [41], Indonesia [42], Japan [43], Malaysia [44], New Zealand [45], Philippines [46], South Korea [47], Taiwan [48], Thailand [49] and Vietnam [50]. As is evident from the next section of this publication, lack of clinical guidance is not the key issue, rather it is lack of implementation of available guidance.

The secondary fracture prevention care gap in Asia Pacific

Delivery of secondary fracture prevention has been evaluated in primary studies and analyses from Australia [51], China [52, 53], Hong Kong [54], India [55], Japan [56,57,58], Malaysia [59], New Zealand [60], South Korea [61,62,63,64] and Thailand [65]. Summaries of these studies and analyses follow.

Australia

In 2016, the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society (ANZBMS) developed a Secondary Fracture Prevention (SFP) Programme Initiative [66] which included a SFP Programme Resource Pack [51]. This document included an analysis of the secondary prevention management gap in Australia. A series of audits undertaken at the national and local level reported that 9–28% and 6–21% of fracture patients received osteoporosis treatment, respectively.

China

In 2015, Xia et al. undertook a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of women aged 50 years and older who were admitted to hospital with a low-trauma hip or vertebral fracture during the period 2008–2012 [52]. Osteoporosis was diagnosed in 57% of patients overall. Bone density testing had ever been conducted in 58% of patients. After the index fracture, almost 70% received supplements and/or osteoporosis-specific medications. Less than half of this group received osteoporosis-specific medication. In 2016, Rath et al. compared specific measures of hip fracture care and secondary prevention for hip fracture patients admitted to a Beijing tertiary hospital in 2012 (n = 780) with the findings of the UK National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) for hip fracture patients presenting to 180 UK hospitals in the same year (n = 59,365) [53]. Key findings included:

Proportion of patients who received osteoporosis assessment: 0.3% of patients in Beijing versus 94% in the UK.

Proportion of patients who received falls assessment: 3.8% of patients in Beijing versus 92% in the UK.

Hong Kong

In 2017, Leung et al. compared care provided to hip fracture patients in Hong Kong in 2012 with that documented in the UK NHFD report for the same year [54]. Findings of relevance to secondary fracture prevention included:

Proportion of patients discharged on bone protection medication: 23% in Hong Kong versus 69% in the UK.

Proportion of patients who received falls assessment: 98% in Hong Kong versus 92% in the UK.

India

In 2017, Rath et al. evaluated the care of hip fracture patients in three major teaching hospitals in Delhi [55]. Among individuals who sustained hip fractures during the period September 2014 to March 2015, only 10% received falls assessment and were prescribed antiresorptive therapy combined with calcium and vitamin D supplements on discharge.

Japan

In 2012, Hagino et al. investigated the risk of a second hip fracture in patients after a first hip fracture [56]. Less than a fifth (19%) were initiated on osteoporosis treatment during their hospital stay, and among these patients, just over a third (37%) continued to take treatment for 12 months after the fracture. In 2015, Baba et al. evaluated the proportion of distal radius fracture patients who were offered secondary preventive care by trauma surgeons [57]. Bone density examination after fracture was performed in 9% of patients (n = 126), and treatment for osteoporosis was initiated in 74% (n = 93) of those who underwent bone mineral density (BMD) examination after fracture. In 2017, Iba et al. compared rates of post-fracture osteoporosis treatment by surgeons for the periods 2000–2003 and 2010–2012 [58]. In the earlier period, 13.1% of fracture patients received osteoporosis medication as compared with 16.2% a decade later.

Malaysia

In 2017, Yeap et al. described care of individuals who presented with a hip fracture to a private hospital in Malaysia during 2010–2014 [59]. Just over a quarter of patients (28%) were initiated on osteoporosis-specific treatment. The overall mean duration of treatment was 3.35 ± 4.44 months (standard deviations), while the median was 1.0 month (IQR, 2.5 months). This reflected the fact that almost a quarter of patients who received osteoporosis-specific treatment (17/72) received intravenous zoledronic acid.

New Zealand

In 2017, Braatvedt et al. described the care of individuals aged ≥ 50 years who sustained a fragility fracture in Auckland during 2011–2012 [60]. Just under a quarter of patients (24%) were prescribed a bisphosphonate within 12 months of their fracture.

South Korea

In 2014, Kim et al. investigated osteoporosis treatment rates among individuals who presented with hip fractures to hospitals in Jeju Island during the period 2008–2011 [61]. Less than a quarter of patients (23%) received osteoporosis treatment after the fracture. In 2015, Kim et al. undertook a cross-national study to evaluate post-hip fracture osteoporosis treatment rates in South Korea, the USA and Spain [62]. Within 3 months of hip fracture, 39% of the South Korean patients had filled at least one prescription for osteoporosis medication. In 2017, Yu et al. evaluated a large national dataset of individuals (n = 6307) who sustained hip fractures during 2013–2014 [63]. One-third of these patients (33.5%) received a prescription for a specific osteoporosis treatment. In 2018, Jang et al. evaluated a very large national dataset of individuals (n = 556,410) who sustained their first fragility fracture between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2012 [64]. Differences in post-fracture osteoporosis treatment were evident between sexes, with 41.7% of women compared with only 19.3% of men receiving osteoporosis-specific treatment within 6 months of fracture.

Thailand

In 2013, Angthong et al. evaluated BMD testing and osteoporosis treatment rates for individuals admitted to an orthopaedic department during the period 2010–2011 [65]. Bone density testing was undertaken for 38% of patients. Among those with diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis, 33% were treated with calcium, vitamin D and bisphosphonates.

Regional studies

In 2013, Kung et al. investigated factors which influence the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture among postmenopausal women in Asian countries [67]. Patient surveys and medical charts of postmenopausal women (N = 1122) discharged after a hip fracture from treatment centres in mainland China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand between July 1, 2006 and June 30, 2007 were reviewed for BMD measurement, osteoporosis diagnosis and osteoporosis treatment. Key findings included:

28% of patients underwent BMD measurement.

52% were informed that they had osteoporosis.

33% received treatment for osteoporosis within 6 months of discharge.

Notably, a history of previous fracture was not associated with an osteoporosis diagnosis.

A systematic approach to fragility fracture care and prevention

During the last two decades, efforts to develop and drive broad adoption of a systematic approach to fragility fracture care and prevention have been undertaken at the national and international level [30]. The national strategy developed by Osteoporosis New Zealand serves as an exemplar of a systematic approach throughout the life-course and is illustrated in Fig. 4 [68].

A systematic approach to fragility fracture care and prevention [68]. Reproduced with kind permission of Osteoporosis New Zealand

Individuals who have sustained hip fractures are considered to be the highest priority group with respect to bone health and falls risk. The need for effective orthogeriatric co-care of patients admitted to hospital with hip fractures is well recognised in professional guidance [69, 70]. Such “orthogeriatric service” (OGS) models of care focus on expediting surgery, ensuring optimal management of the acute phase through adherence to a care plan overseen by senior orthopaedic and geriatrician/internal medicine personnel and delivery of secondary fracture prevention through osteoporosis management and falls prevention.

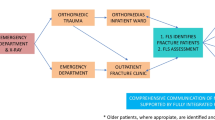

The complementary Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) model of care ensures that all patients aged 50 years or over, who present to urgent care services with a fragility fracture at any skeletal site, undergo fracture risk assessment and receive treatment in accordance with prevailing national clinical guidelines for osteoporosis. The FLS also ensures that falls risk is addressed among older patients through referral to appropriate local falls prevention services.

These two service models are entirely complementary. As adoption of OGS for hip fracture sufferers becomes more widespread, OGS are increasingly likely to deliver secondary preventive care for these patients. As hip fractures constitute approximately 20% of all clinically apparent fragility fractures [71], in health systems which have implemented an OGS, FLS will provide secondary preventive care for the other 80% of fragility fracture sufferers who have experienced fractures of the wrist, humerus, spine, pelvis and other sites.

In July 2018, a Global Call to Action to improve the care of people with fragility fractures was published [72]. The Call to Action stated that there is an urgent need, globally, to improve:

Acute multidisciplinary care for the person who suffers a hip, clinical vertebral and other major fragility fractures.

Rapid secondary prevention after first occurrence of all fragility fractures, including those in younger people as well as those in older persons, to prevent future fractures.

Ongoing post-acute care of people whose ability to function is impaired by hip and major fragility fractures.

The Call to Action highlighted OGS and FLS as the optimal models of care to achieve these goals. Endorsement of the Call to Action was sought from organisations representing geriatrics, orthopaedics, osteoporosis/metabolic bone disease, rehabilitation and rheumatology. On publication, 81 organisations at the global level, regional level (Asia Pacific, Europe, Latin America, Middle East and Africa) and at the national level for five highly populated countries (Brazil, China, India, Japan and the USA) had endorsed the Call to Action.

Descriptions of implementation of OGS—and hip fracture registries to benchmark the care that they provide against clinical care standards—and FLS in the Asia Pacific region follow.

The orthogeriatric model of care, clinical standards and the emergence of hip fracture registries in Asia Pacific

Australia and New Zealand

A major effort to improve acute hip fracture care and secondary prevention after hip fracture has been led by the Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) [73]. Key steps in this bi-national quality improvement initiative during the last 7 years have included:

2011: The first meeting of clinicians from Australia and New Zealand was convened to consider how experience from elsewhere could inform development of a hip fracture registry for both countries.

2013: The first ANZHFR Facilities Level Audit was published [73], which assessed and documented what services, resources, policies, protocols and practices existed across Australia and New Zealand hospitals in relation to hip fracture care.

2014: Publication of the Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care [70] and the second ANZHFR Facilities Level Audit [73].

2015: Development and roll-out of the ANZHFR in both countries and publication of the third ANZHFR Facilities Level Audit [73]. In New Zealand, the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) allocated NZ$300,000 to support implementation and development of the New Zealand arm of ANZHFR from January 2016 to December 2018. ACC is the Crown Entity in New Zealand responsible for managing a national no-fault scheme for people who sustain accidental injuries.

2016: Publication of the Hip Fracture Care Clinical Care Standard by the Australian Commission in collaboration with the Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand [74], publication of the ANZHFR 2016 Annual Report [75], which included the first ANZHFR Patient Level Audit and the fourth ANZHFR Facilities Level Audit.

2017: Publication of the ANZHFR 2017 Annual Report [76], which included the second ANZHFR Patient Level Audit and the fifth ANZHFR Facilities Level Audit.

2018: Publication of the ANZHFR 2018 Annual Report [77], which included the third ANZHFR Patient Level Audit and the sixth ANZHFR Facilities Level Audit. As of September 2018, ANZHFR held a total of 25,792 records from 70 hospitals across both countries [78]. This included 95% (21/22) of hospitals in New Zealand and 62% (59/95) of hospitals in Australia. The Australian Government allocated AU$300,000 to build capacity of the Australian arm of ANZHFR during 2018-2020 [79].

The ANZHFR 2018 Annual Report included data on 9408 hip fracture patients from 56 hospitals across both countries [77]. This represented approximately 48% of all public hospitals that were treating hip fractures at the time. Findings in relation to the seven Quality Statements of the Hip Fracture Care Clinical Care Standard included [74]:

Quality statement 1—Care at presentation: 78% of hospitals reported having a hip fracture pathway, 56% across the whole acute hip fracture patient journey and 22% in the emergency department only.

Quality statement 2—Pain management: 56% of hospitals responded that they had a pathway for pain management in hip fracture patients, 32% across the whole acute patient journey and 24% in the emergency department only.

Quality statement 3—Orthogeriatric model of care: 55% of hospitals reported an orthogeriatric service for older hip fracture patients: 32% utilising a daily geriatric medicine liaison service and 23% utilising a shared-care arrangement with orthopaedics.

Quality statement 4—Timing of surgery: 80% and 77% of patients in New Zealand and Australia, respectively, were reported as being operated on within 48 hours of presentation to hospital.

Quality statement 5—Mobilisation and weight bearing: 87% and 89% of patients in New Zealand and Australia, respectively, are offered the opportunity to mobilise on the first day after surgery.

Quality statement 6—Minimising risk of another fracture: 25% and 24% of patients in New Zealand and Australia, respectively, were receiving bone protection medication at discharge from hospital.

Quality statement 7—Transition from hospital care: Of those that lived at home prior to injury and of the patients followed up at 120 days, 76% and 71% of patients in New Zealand and Australia, respectively, have returned to their own home at 120 days.

Hong Kong

In 2012, the care of hip fracture patients admitted to six acute major hospitals in Hong Kong was recorded in a registry [54]. The care of these 2914 patients in Hong Kong was compared to that provided to 59,365 hip fracture patients in the UK, as reported in the 2012 Annual Report of the UK NHFD [80]. Performance against the six standards for hip fracture care proposed in the British Orthopaedic Association—British Geriatrics Society Blue Book on the care of patients with fragility fracture [81] is shown in Table 2. The authors concluded that regular orthogeriatric co-management was required to improve management of the acute episode and implementation of FLS was a priority to improve secondary fracture prevention in relation to treatment of osteoporosis.

In 2018, Leung et al. described the impact of a Comprehensive Fragility Fracture Management Programme (CFFMP) for people who sustained hip fractures in Hong Kong [82]. The processes of care and outcomes were compared for patients who presented to the Prince of Wales Hospital (n = 76) which operated the CFFMP with those delivered at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital (n = 77) which provided conventional care. While the study population was relatively small, a statistically significant difference was observed between re-fracture rates during 18 months follow-up (CFFMP, 1.3% vs. conventional care, 10.4%, relative risk 0.127 [95% confidence interval, 0.016–0.988, p value, 0.034]). Significant benefits were also observed in terms of results for the elderly mobility scale and falls risk screening.

India

In 2017, Rath et al. evaluated current management of hip fractures in three major public tertiary care hospitals in Delhi [55]. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from healthcare providers, patients, carers and medical records during the period September 2014 to March 2015. Of 136 hip fracture patients, 85 (63%) were admitted to hospital, with lack of beds being the reason for patients not being admitted. Just under half (48%) of admissions to an orthopaedic ward were done so within 24 h of the injury, while a fifth were admitted more than 48 h after injury. More than 96% of patients received surgery, of whom 30% received surgery within 48 h of hospital admission. More than a fifth of patients (21%) were operated on 2 weeks after hospitalisation. The authors concluded that development and implementation of national guidelines and standardized protocols for older people with hip fractures in India are needed to drive a much-needed change in practice.

Japan

In 2017, the Fragility Fracture Network Japan (FFN-J) began the development and roll-out of the Japan National Hip Fracture Database (JNHFD) [83]. The common minimum dataset developed by the global Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) [84] was translated into Japanese and used as the basis for data collection by the 20 hospitals which joined this initiative during 2017. It is the intention of FFN-J to facilitate nationwide participation in the JNHFD and to work with policymakers to explore the potential for development of incentives which link quality of care to levels of reimbursement for hospitals that manage hip fracture patients.

Singapore

In 2014, Doshi et al. described initial experience and short-term outcomes of an orthogeriatric model of care for hip fracture patients established at Tan Tock Seng Hospital in Singapore [85]. The model was based on the following features:

Timely admission, review, surgery, rehabilitation and transfer

A multidisciplinary approach which included co-management approach from the orthopaedic surgeon and geriatrician

A care manager who was responsible for ensuring that delivery of care was in accordance with an integrated care pathway

Key findings included:

Thirty-seven percent of patients underwent surgery within 48 h

The mean post-surgical length of stay was 10 days

Statistically significant increases in the mean functional score (Mean Barthel Index, p < 0.01) were evident when comparing MBI values at discharge (59.6) to those at 6 months (80.8) and 12 months (87.0), which were comparable to pre-injury levels (91.2)

Fracture Liaison Services, evidence of effectiveness and clinical standards in Asia Pacific

Australia and New Zealand

In 2015, ANZBMS published a position paper and call to action on secondary fracture prevention which was endorsed by healthcare professional organisations and government agencies from both countries [86]. The paper called for a proactive dialogue between Federal, State and local governments, learned societies, consumer groups and other interested organisations to ensure that best practice in secondary fracture prevention was consistently delivered. In 2016, ANZBMS published a comprehensive suite of educational resources to support implementation efforts, which included an analysis [87] of published studies from Australian FLS [88,89,90,91,92,93] based on the classification system reported by Ganda et al. in a systematic review and meta-analysis [94]. This system classified FLS as type A to type D:

Type A FLS models: Identifies fracture patients, organises investigations and initiates osteoporosis treatment, where appropriate, for fragility fracture patients. A “3i” FLS model.

Type B FLS models: Identifies and investigates but leaves the initiation of treatment to the primary care provider (PCP). A “2i” FLS model.

Type C FLS models: Fracture patients receive education about osteoporosis and receive lifestyle advice including falls prevention. The patient is recommended to seek further assessment and the PCP is alerted that the patient has sustained a fracture and that further assessment is needed. This model does not undertake BMD testing or assessment of need for osteoporosis treatment. A “1i” FLS model.

Type D FLS models: Provides osteoporosis education to the fracture patient. Type D models do not educate or alert the primary care provider. A “Zero i” FLS model.

A summary of the findings of the ANZBMS analysis is provided in Table 3. Historical control groups and/or lower intensity intervention groups were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the particular FLS model. Consistent with the findings of Ganda’s meta-analysis, a higher proportion of fracture patients managed by a 3i FLS model underwent BMD testing and received osteoporosis treatment as compared with the less intensive interventions. Two studies reported statistically significant differences in re-fracture rates between 3i intervention groups versus less intensive control groups.

In 2016, Kim et al. published the first report of a FLS in New Zealand [95]. This FLS could be described as a mixed 3i/2i model. Fracture patients aged over 75 years were routinely recommended to initiate treatment with a bisphosphonate while patients aged 50 to 75 years underwent BMD testing and absolute fracture risk assessment using the FRAX® and/or Garvan tools. Almost a quarter of patients (24%, n = 71) were on pre-existing specific osteoporosis treatment, which was primarily bisphosphonates (n = 63), and a small proportion (1%, n = 4) were taking a bisphosphonate “drug holiday” deemed to be appropriate by the authors. Among the three-quarters of treatment naïve patients (n = 226), the majority (58%, n = 131) were treated directly by FLS personnel with intravenous (i.v.) zoledronic acid or a recommendation was made to the patient’s PCP to organise a zoledronic acid infusion or initiate treatment with an oral bisphosphonate. In total, 68% (n = 206) of the fracture patients identified by the FLS during 2014 were administered or recommended treatment. Follow-up of patients who were alive 12 months after the incident fracture established that 70% continued to take osteoporosis treatment.

In 2016, Osteoporosis New Zealand (ONZ) published Clinical Standards for Fracture Liaison Services in New Zealand [96]. These clinical standards were based on the so-called 5IQ structure: identification, investigation, information, intervention, integration and quality. The clinical standards were widely endorsed by healthcare professional organisations and government agencies and provide a mechanism for FLS in New Zealand to benchmark the care that they provide against internationally recognised best practice. The ONZ clinical standards are adherent to the principles of the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) Capture the Fracture® standards [97] described below and encourage FLS in New Zealand to submit their service for IOF Best Practice Recognition.

China

In 2019, investigators from Beijing Jishuitan Hospital described the impact of a multidisciplinary co-management programme for older hip fracture patients (n = 3540) [98]. Jishuitan Hospital is one of China’s leading orthopaedic hospitals which has approximately 1500 beds and performs 40,000 orthopaedic operations per year. This initiative was led by an orthopaedic surgeon and a geriatrician, working in collaboration with emergency physicians, anaesthesiologists and physiotherapists. The effect of the co-management programme on a range of process measures was reported for the period May 2015 to May 2017, and compared to pre-intervention rates, which included:

Osteoporosis assessment: 76.4% of co-managed patients versus 19.2% of pre-intervention patients (adjusted odds ratio [OR] and 95% confidence interval [CI] 13.88 [11.59, 16.63], p < 0.0001).

Falls assessment: 99.4% of co-managed patients versus 99.7% of pre-intervention patients (adjusted OR and 95% CI: 0.54 [0.15, 1.92], p = 0.43).

The authors concluded that the model of care developed in this study has the potential to be adopted in other hospitals across China. Further, large-scale cluster randomized controlled trials were proposed to evaluate the impact of such models on patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

Japan

In 2012, a 3i FLS model was implemented at Niigata Prefectural Central Hospital for patients who had sustained a primary hip fracture [99]. Approximately one-fifth (21%) of historical control group patients managed in 2009 received post-hip fracture osteoporosis treatment, as compared to 33%, 41% and 43% of patients in 2012, 2013 and 2014, respectively. The investigators also evaluated the incidence of contralateral hip fracture. At 24 months, 12%, 8% and 5% of patients had sustained a contralateral hip fracture in 2009, 2012 and 2013, respectively.

Singapore

In 2008, the Singapore Ministry of Health funded the establishment of the Osteoporosis Patient Targeted and Integrated Management for Active Living (OPTIMAL) FLS programme in five public hospitals in Singapore. The OPTIMAL programme was subsequently expanded to include the 18 polyclinics in Singapore.

In 2013, Chandran et al. described implementation and results of OPTIMAL at Singapore General Hospital for the period 2008–2012, which is a mixed 3i/2i model [100]. While more than a thousand fracture patients were managed by the FLS during the 4-year period, the publication presented results for 287 patients who had completed 2-year follow-up as of August 2012. Almost all (98%) patients had BMD testing conducted upon enrollment into the programme and the majority (63%) had a 2-year follow-up BMD test completed. A third of patients (n = 95) were on pre-existing specific osteoporosis treatment. Among the two-thirds of treatment naïve patients (n = 192), almost all (n = 187) were initiated on treatment by an OPTIMAL physician or a recommendation was made to the patient’s PCP to initiate treatment.

At 2-year follow-up, compliance was assessed by medication possession ratio (MPR). The MPR percentage was calculated as (duration of pharmacy refills / duration of medications prescribed) multiplied by 100. At 2 years, the mean MPR was 73%. In 2016, an analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with non-adherence to the programme [101]. The number of patients with 2-year follow-up had increased to 938, of whom a quarter (n = 237) had defaulted for a period of the follow-up. The median MPR among the patients who defaulted was 12% (interquartile range: 4–37%). Multivariate analysis revealed the following factors to be correlated with noncompliance:

Non-Chinese patients were almost twice as likely to be noncompliant compared with Chinese patients (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.98, p = 0.001).

Patients with primary school education or below were almost two-thirds more likely to be noncompliant compared with individuals with higher education levels (aHR 1.65, p = 0.013).

Patients with nonvertebral and/or multiple fractures were 38% more likely to be noncompliant than individuals with vertebral fractures (aHR 1.38, p = 0.018).

Taiwan

In 2016, Chan et al. described development of the Taiwan FLS Network [102]. The first FLS in Taiwan was established in 2014 by the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). The Taiwanese National Health Insurance (NHI) system reimburses osteoporosis medications for individuals who have sustained hip or vertebral fractures with low BMD. Consequently, FLS in Taiwan currently focus on these two types of fracture. In 2015, the NTUH FLS programmes at the main hospital site and at the branch site at Bei-hu were accredited on the IOF Capture the Fracture® Map of Best Practice (which is discussed in detail below) [103].

In 2016, the Taiwanese Osteoporosis Association (TOA) organised a series of workshops to drive awareness of the FLS model and expedite widespread adoption across Taiwan. These workshops were led by clinicians who has established FLS in 2014–2015, and the first workshop which was held in September 2016 resulted in 12 institutions beginning the process of FLS development. Subsequent workshops, ongoing sharing of best practice between sites and presentations at the Annual TOA Scientific Meeting have resulted in 24 FLS being operational in Taiwan as of February 2019, 17 of which feature on the IOF Map of Best Practice. The TOA-led initiative was recognised by IOF at the 2017 World Congress for Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases held in Florence and granted the Best Secondary Fracture Prevention Promotion award [104].

In January 2019, representatives of TOA engaged in negotiation with the administration of the National Health Insurance system with the aim of securing public reimbursement for FLS in Taiwan. The most recent publication from Taiwanese FLS investigators described risk factors for poor functional recovery, mortality, recurrent fractures and falls among patients managed by FLS [105].

Thailand

In 2014, Amphansap et al. described a 3i FLS model implemented at Police General Hospital in Bangkok for patients who had sustained a hip fracture [106]. The results of the intervention compared to the historical control group are shown in Table 4. It should be noted that the majority (68%) of individuals treated for osteoporosis in the intervention group received either calcium alone or calcium and vitamin D. The authors attributed this to the comparatively high cost of anabolic or antiresorptive therapies.

IOF Capture the Fracture® Best Practice Framework in the Asia Pacific region

IOF launched the Capture the Fracture® Programme in 2012 with publication of the World Osteoporosis Day thematic report [21]. Capture the Fracture® has since become one of IOF’s leading initiatives, the key components of which are:

Website: The Capture the Fracture® website—www.capturethefracture.org—provides a comprehensive suite of resources to support healthcare professionals and administrators to establish a new FLS or improve an existing FLS.

Webinars: An ongoing series of webinars provide an opportunity to learn from experts across the globe who have established high-performing FLS. As of August 2018, webinars had been conducted in Chinese, Dutch, English, French, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese and Spanish.

Best Practice Framework: The Best Practice Framework (BPF), which is currently available in nine major languages, sets an international benchmark for FLS by defining essential and aspirational elements of service delivery. The BPF serves as the measurement tool for IOF to award Capture the Fracture® Best Practice Recognition status. The 13 globally endorsed standards of the BPF were published in Osteoporosis International [97] in 2013 and are as follows:

- 1.

Patient Identification Standard

- 2.

Patient Evaluation Standard

- 3.

Post-fracture Assessment Timing Standard

- 4.

Vertebral Fracture Standard

- 5.

Assessment Guidelines Standard

- 6.

Secondary Causes of Osteoporosis Standard

- 7.

Falls Prevention Services Standard

- 8.

Multifaceted health and lifestyle risk-factor Assessment Standard

- 9.

Medication Initiation Standard

- 10.

Medication Review Standard

- 11.

Communication Strategy Standard

- 12.

Long-term Management Standard

- 13.

Database Standard

In October 2017, the FLS Consensus Meeting was hosted by TOA in Taipei, Taiwan and endorsed by IOF, AFOS and Asia Pacific Osteoporosis Foundation (APOF) [107]. The purpose of the meeting was to review the 13 BPF standards and determine if they were appropriate for benchmarking the performance of FLS in the Asia Pacific region. International and domestic experts reviewed the standards and concluded that they were generally applicable in the Asia Pacific region and needed only minor modifications to fit the healthcare settings in the region.

As of January 2019, 67 FLS from the Asia Pacific region had been submitted for Best Practice Recognition status, with 41 having been fully evaluated and a further 26 at various stages of the review process [103]. These included FLS from Australia, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Thailand.

Health policy on models of care for secondary fracture prevention

Australia

Management of osteoporosis and prevention of fragility fractures have featured in the Australian Commonwealth Government strategy since 2002. The National Health Priority Areas (NHPA) initiative [108] was Australia’s response to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Strategy Health for All by the year 2000 [109] and included musculoskeletal conditions. In 2005, the National Action Plan for Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoporosis included efforts to promote post-fracture assessment [110] and the associated National Service Improvement Framework (NSIF) [111] noted a major post-fracture care gap. The NSIF proposed that the following issues underpinned the observed failure to consistently deliver secondary preventive care:

Lack of knowledge about the implications of fractures and opportunities to reduce the risk of further fractures.

Lack of integration of hospital, medical and surgical services.

Uncertainty over who is responsible for initiating investigation and who will follow-up the results of diagnostic tests.

The NSIF stated that people should have access to optimal follow-up care to prevent future avoidable admissions to hospital, including:

Processes will be in place to initiate bone density testing following low trauma fractures, and to commence appropriate osteoporosis management.

The national policy documents were intended to provide a framework that would guide an implementation process within each of the jurisdictions. Unfortunately, this promising policy framework has not resulted in significant improvements in the secondary prevention of fragility fractures across Australia. The 2018 ANZHFR report noted that just 24% of hip fracture patients managed by Australian hospitals that were participating in the registry in 2017 received treatment for osteoporosis at discharge from the acute setting. Further, only 36% of hospitals in Australia and New Zealand reported having a FLS.

While progress at the national level has been limited, in Australia’s most populous state, the New South Wales (NSW) Government Agency for Clinical Innovation (ACI) has focused on state-wide implementation of FLS. The ACI Musculoskeletal Network first published the Model of care for osteoporotic refracture prevention in 2011, which was updated in 2017 [112]. The NSW Ministry of Health directed all state-funded health districts to implement the model of care in 2017/18 financial year. As of May 2018, the model of care had been implemented in 19 (76%) of the 25 Local Health Districts across the state [113].

Hong Kong

In 2017, the Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HKHA) approved three public hospitals to develop the FLS model in Hong Kong [114]. Three advanced practice nurses have been appointed as Fracture Liaison Nurses in different hospital clusters.

New Zealand

In 2012, Osteoporosis New Zealand (ONZ) published BoneCare 2020: A systematic approach to hip fracture care and prevention for New Zealand [68]. The objectives of this strategy are illustrated in Fig. 4, which called for formation of a “National Fragility Fracture Alliance” comprised of all relevant stakeholder organisations to collaborate to deliver system-wide quality improvement. In short, this is precisely what followed during the next 6 years [115]:

In 2013, the Ministry of Health published annual planning guidance for District Health Boards (DHBs) which stated that DHBs should establish FLS.

In 2014, the ANZHFR Steering Group published clinical guidelines on the management of hip fracture for Australia and New Zealand [70]. Osteoporosis New Zealand published resources to support DHBs to establish FLS [116].

In 2015, the ANZHFR was launched. As of September 2018, the New Zealand arm of the ANZHFR had 5714 records, 21 of 22 New Zealand hospitals had completed ethics and governance approvals to contribute data and 19 of these were contributing data [78].

In 2016, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care in collaboration with the Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand published a clinical standard for hip fracture care, which included a standard relating to secondary fracture prevention [74]. ONZ published clinical standards for FLS which were endorsed by 15 organisations [96]. The Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) announced an investment of NZ$30.5 million to improve falls and fragility fracture care and prevention across New Zealand [117].

In 2017, the National Fragility Fracture Alliance was formalised under the Live Stronger for Longer initiative, which is comprised of all relevant government agencies, NGOs and other stakeholders [38]. A Falls and Fractures Outcomes Framework has been developed to assess the impact of the activities described above [118]. The Outcomes Framework describes five domains which are populated with a range of measures pertaining to falls and fracture care, including quarterly data on the number of individuals seen by FLS and those participating in community-based strength and balances classes.

Singapore

Since 2008, as described above, the Singapore Ministry of Health has funded the Osteoporosis Patient Targeted and Integrated Management for Active Living (OPTIMAL) FLS programme [100].

Thailand

The Government of Thailand has developed a policy to implement a nationwide Refracture Prevention Programme. In March 2018, the first Thailand FLS Forum and Workshop was held in Bangkok. During this meeting, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed to launch a public-private partnership between Lerdsin Hospital, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health of Thailand and Amgen (Thailand) Limited [119].

The components of the Asia Pacific Bone Academy FLS education initiative

During 2017, the Asia Pacific Bone Academy (APBA) Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) Focus Group developed a multi-faceted educational initiative relating to FLS implementation in the Asia Pacific region [120]. This initiative provides healthcare professionals and health administrators with a suite of tools to support development of new FLS across the region which includes:

The FLS Toolbox describes the epidemiology and costs of fragility fractures, where published data are available, for the following countries and regions [121]: Australia, mainland China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. A summary of published findings of evidence for effectiveness of FLS is provided for FLS based in Japan [99], New Zealand [95], Singapore [100] and Thailand [106]. A generic FLS business plan template, which is available in an editable electronic format, explains why FLS are required, how they can be organised to deliver optimal post-fracture care and what benefits can be realized, in terms of improved patient management, reduced secondary fracture incidence and reduced healthcare costs. Estimates of potential cost savings through widespread implementation of FLS at the national level are provided for countries throughout the region. Additional sections of the FLS Toolbox provide step-by-step advice on establishing a FLS, practical tools including generic job descriptions and links to useful online resources.

Demonstrating the health economic impact of FLS is a key component of the business planning process. The FLS benefits calculator provides an estimation of financial savings that could be achieved by implementing a successful FLS [122]. This calculator provides estimation of financial savings upon implementing a successful FLS in 12 countries or regions across Asia, including Australia, China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. This tool is designed for use by various stakeholders, including policymakers, healthcare providers, community services and clinical societies. The calculator is customised to calculate costs saved in either public or private settings in each country or region, except for China which is subdivided into either Tier 1 cities or New Tier 1 cities. Users have an option to enter their own values if known or to choose the default values which were calculated from regional demographical, financial and epidemiological statistics.

The Kaiser Permanente Healthy Bones Programme established at centres across the USA is one of the most successful secondary fracture prevention initiatives in the world [123]. During the last 17 years of operations, the Healthy Bones Team has developed numerous materials to support the programme. Kaiser Permanente generously shared these materials with both the US National Bone Health Alliance and the APBA FLS Focus Group to support these groups’ FLS educational initiatives [120, 124]. Most of the materials are fully editable and so can be tailored for local use.

The FLS Toolbox, Benefits Calculator and Coordinator materials were provided as resources to support FLS workshops which immediately followed the 5th Scientific Meeting of the Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies (AFOS) held in Kuala Lumpur in October 2017. The FLS workshops were attended by a broad range of healthcare professionals and addressed three key themes:

The FLS business case.

Planning the FLS patient pathway.

The role of the FLS coordinator in fragility fracture care management.

During the remainder of 2017 and the first half of 2018, the resources were used to support additional FLS workshops delivered at conferences in Hong Kong and South Korea.

The impact of the Asia Pacific Bone Academy FLS education initiative

In order to assess the impact of the APBA FLS Focus Group initiative on development and implementation of FLS in the Asia Pacific region during the year after the 2017 AFOS Scientific Meeting, during August and September 2018, a follow-up survey was issued to the 142 workshop participants. The findings of the survey were presented as an oral communication at the IOF Regional 7th Asia Pacific Osteoporosis Conference in Sydney, Australia, November 2018 [125]. A total of 43 FLS workshop participants (30.3%) completed the follow-up survey, which included:

Twenty-three respondents who had a FLS established in their workplace when the survey was conducted.

Twenty respondents who did not have a FLS established in their workplace when the survey was conducted.

All of those who had a FLS established consented for their de-identified data to be included in the survey analysis. Survey findings among this group included:

69.6% of FLS were established prior to participation in the AFOS 2017 Workshops.

95.7% of respondents stated that participation in the AFOS 2017 Workshops supported their efforts to establish a FLS.

73.9% of respondents stated that the FLS Toolbox for Asia Pacific supported their efforts to establish a FLS.

78.3% of respondents stated that a multidisciplinary team was established to develop the business case for their FLS.

87.0% of respondents stated that a multidisciplinary team was established to design the patient pathway for their FLS.

26.1% of respondents stated that their FLS has sustainable funding.

The primary source of funding for FLS was from public hospitals (83.3%) as compared to private hospitals (16.7%).

Almost 90% of those who had not established a FLS consented for their de-identified data to be included in the survey analysis. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the majority of these hospitals were either in the process of setting-up a FLS (47%) or had plans in place to establish a FLS for which approval is being sought (29%). The primary barrier to establishing a new FLS was lack of sustainable funding.

The survey findings suggest that the APBA FLS Focus Group educational initiative has stimulated implementation of some new FLS across the Asia Pacific region. Limitations of the survey included the biases inherent to surveys, potential self-selection bias as survey completion was voluntary with a minority of participants completing the survey, the use of closed-ended survey questions and the self-reported nature of survey responses which were not independently validated. The authors intend to devise more comprehensive and rigorous evaluations of subsequent iterations of the FLS education initiative in the future.

Future opportunities

The FLS Toolbox is currently being updated to accommodate the educational needs of clinicians and hospitals at three distinct stages of FLS implementation:

For hospitals with no FLS in place.

For hospitals where a FLS pilot has been approved or the FLS pilot was successful and broader adoption is being rolled-out.

For hospitals where a FLS pilot has been running for a while, and needs evaluation, or a FLS was attempted but failed and needs review.

Additional FLS workshops and educational initiatives to support FLS implementation across Asia Pacific included programmes at the following meetings in November 2018:

Asia Pacific Bone Academy 2018, Taipei, Taiwan [126].

FFN Asia Pacific Regional Expert Meeting, Tokyo, Japan [127].

IOF Regional 7th Asia-Pacific Osteoporosis Conference, Sydney, Australia [128].

Furthermore, in May 2018, representatives of the following regional, national and international organisations participated in an Asia Pacific Regional Fragility Fracture Summit in Singapore [129]:

Regional organisations:

Asia-Oceania Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine.

Asia Pacific Geriatric Medicine Network.

Asia Pacific Orthopaedic Association.

Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies.

National organisations:

Australian SOS Fracture Alliance.

FFN China.

Osteoporosis Society of Singapore.

Thai Osteoporosis Foundation.

International organisations:

FFN.

IOF.

International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD).

The primary objective of the Summit was to explore the benefits and challenges of establishing a regional fragility fracture alliance for the Asia Pacific region to improve the acute management, rehabilitation and secondary prevention of fragility fractures. It was proposed that a regional alliance could provide a mechanism to bring together the expertise of regional, national and international expert groups to devise and facilitate implementation of a strategy to expedite these goals throughout the region. The Summit participants agreed that a regional alliance was needed, with the objectives to drive policy change, improve awareness and change political and professional mindset to facilitate optimal fragility fracture management across the Asia Pacific region. The Asia Pacific Fragility Fracture Alliance (APFFA), which was led by Dato’ Dr Lee Joon Kiong (Malaysia) and Associate Professor Derrick Chan (Taiwan) as co-chairs, was launched on 29th November 2018, immediately prior to the IOF Regional 7th Asia-Pacific Osteoporosis Conference in Sydney, Australia [130]. The APFFA Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed by all the participating organisations with the objective of achieving successful implementation of the three main pillars of orthogeriatric care for patients presenting with fragility fractures [72], namely providing:

Appropriate post-fracture acute care.

Post-fracture treatment rehabilitation to regain maximal functional outcome.

Secondary fracture prevention.

Conclusions

The Asia Pacific region is home to more than half of the population of humankind and is ageing rapidly. The age structure of this population is set to undergo an unprecedented demographic shift in the coming decades, resulting in the proportion of individuals who will be aged ≥ 65 years increasing several fold as compared with those younger individuals currently considered to be of working age. Maintaining the mobility and, therefore, independence of older people will make a significant contribution to enabling national societies and the policymakers that lead them to adjust to the realities of this new demographic era.

Prevention of osteoporosis and falls—and the fragility fractures that often result from the combination of these two risk factors—must be recognised as a healthcare priority throughout the Asia Pacific region. The first and, arguably, most obvious step on this journey for better bone health for all must be to ensure that a determined effort is made to make the first fragility fracture the last fragility fracture. Widespread implementation of Fracture Liaison Services provides a healthcare delivery strategy to realise this objective.

The ABPA FLS Focus Group educational initiative is an important first step to drive widespread implementation of FLS. Further development and dissemination of this initiative, in combination with the efforts of FFN, IOF and the recently established Asia Pacific Fragility Fracture Alliance provide an opportunity to establish a new and optimal standard of care for people who sustain fragility fractures across the Asia Pacific region.

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2017) World population prospects: the 2017 revision, key findings and advance tables. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP.248. New York

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. ESA/P/WP/248

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2017) World population prospects: volume II: demographic profiles 2017 Revision. New York

Ebeling PR (2014) Osteoporosis in men: Why change needs to happen. In: Mitchell PJ (ed) World osteoporosis day thematic report. International Osteoporosis Foundation, Nyon

The World Bank (2018) Where we work. http://www.worldbank.org/en/where-we-work. Accessed 20 June 2018

Cheung CL, Ang SB, Chadha M, Chow ES, Chung YS, Hew FL, Jaisamrarn U, Ng H, Takeuchi Y, Wu CH, Xia W, Yu J, Fujiwara S (2018) An updated hip fracture projection in Asia: the Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies study. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 4:16–21

Wang Y, Cui H, Zhang D, Zhang P (2018) Hospitalisation cost analysis on hip fracture in China: a multicentre study among 73 tertiary hospitals. BMJ Open 8:e019147

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2013) The Asia-Pacific regional audit: epidemiology, costs and burden of osteoporosis in 2013. Nyon, Switzerland

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2011) The Eastern European & Central Asian regional audit: epidemiology, costs & burden of osteoporosis in 2010

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2011) The Middle East & Africa regional audit: epidemiology, costs & burden of osteoporosis in 2011

Cooper C, Ferrari S (2017) IOF compendium of osteoporosis. In: Mitchell P, Harvey N, Dennison E (eds) , 1st edn. International Osteoporosis Foundation, Nyons

Watts JJ, Abimanyi-Ochom J, Sanders KM (2013) Osteoporosis costing all Australians a new burden of disease analysis—2012 to 2022. Osteoporosis Australia, Glebe

Jones S, Blake S, Hamblin R, Petagna C, Shuker C, Merry AF (2016) Reducing harm from falls. N Z Med J 129:89–103

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2017) World population prospects 2017: File POP/15-2: annual male population by five-year age group, region, subregion and country, 1950-2100 (thousands). New York

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2017) World population prospects 2017: File POP/15-3: annual female population by five-year age group, region, subregion and country, 1950-2100 (thousands). New York

Lesnyak O, Sahakyan S, Zakroyeva A et al (2017) Epidemiology of fractures in Armenia: development of a country-specific FRAX model and comparison to its surrogate. Arch Osteoporos 12:98

Ebadi Fard Azar AA, Rezapour A, Alipour V, Sarabi-Asiabar A, Gray S, Mobinizadeh M, Yousefvand M, Arabloo J (2017) Cost-effectiveness of teriparatide compared with alendronate and risedronate for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis patients in Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran 31:39

Maalouf G, Bachour F, Hlais S, Maalouf NM, Yazbeck P, Yaghi Y, Yaghi K, El Hage R, Issa M (2013) Epidemiology of hip fractures in Lebanon: a nationwide survey. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 99:675–680

Sadat-Ali M, Al-Dakheel DA, Azam MQ et al (2015) Reassessment of osteoporosis-related femoral fractures and economic burden in Saudi Arabia. Arch Osteoporos 10:37

Tuzun S, Eskiyurt N, Akarirmak U, Saridogan M, Senocak M, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Turkish osteoporosis S (2012) Incidence of hip fracture and prevalence of osteoporosis in Turkey: the FRACTURK study. Osteoporos Int 23:949–955

Akesson K, Mitchell PJ (2012) Capture the fracture: a global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. In: Stenmark J, Misteli L (eds) World Osteoporosis Day Thematic Report. International Osteoporosis Foundation, Nyon

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2017) Capture the Fracture® Programme website. http://www.capture-the-fracture.org/. Accessed 9 Aug 2017

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA 3rd, Berger M (2000) Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res 15:721–739

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C et al (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35:375–382

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2004) Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:175–179

Gallagher JC, Melton LJ, Riggs BL, Bergstrath E (1980) Epidemiology of fractures of the proximal femur in Rochester, Minnesota. Clin Orthop Relat Res 163-171

Port L, Center J, Briffa NK, Nguyen T, Cumming R, Eisman J (2003) Osteoporotic fracture: missed opportunity for intervention. Osteoporos Int 14:780–784

McLellan A, Reid D, Forbes K, Reid R, Campbell C, Gregori A, Raby N, Simpson A (2004) Effectiveness of strategies for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in Scotland (CEPS 99/03). NHS Quality Improvement Scotland

Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Simonelli C, Bolander M, Fitzpatrick LA (2007) Prior fractures are common in patients with subsequent hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 461:226–230

Harvey NC, McCloskey EV, Mitchell PJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Pierroz DD, Reginster JY, Rizzoli R, Cooper C, Kanis JA (2017) Mind the (treatment) gap: a global perspective on current and future strategies for prevention of fragility fractures. Osteoporos Int 28:1507–1529

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Bisphosphonates for treating osteoporosis: Technology appraisal guidance [TA464]. London

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Raloxifene and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women: Technology appraisal guidance [TA161]. London

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2010) Denosumab for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women: Technology appraisal guidance [TA204]. London

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture: Clinical guideline [CG146]. London

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Hip fracture: management: clinical guideline [CG124]. Lonson

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Quality Standard 149: osteoporosis. London

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2012) Quality standard for hip fracture care. NICE Quality Standard 16. London

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Osteoporosis Australia (2017) Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis and management in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years of age 2nd edition. RACGP, East Melbourne VIC

Chinese Society of Osteoporosis and Bone Mineral Research, Chinese Medical Association, (in collaboration with) Department of Medical Administration of the Ministry of Health (2013) The standard of diagnosis, treatment and quality control on osteoporosis. Chinese Society of Osteoporosis and Bone Mineral Research

Oshk Task Group for Formulation of OSHK Guideline for Clinical Management of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis in Hong Kong, Ip TP, Cheung SK et al (2013) The Osteoporosis Society of Hong Kong (OSHK): 2013 OSHK guideline for clinical management of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 19 Suppl 2:1–40

Meeta HC, Marwah R, Sahay R, Kalra S, Babhulkar S (2013) Clinical practice guidelines on postmenopausal osteoporosis: *an executive summary and recommendations. Journal of Mid-life Health 4:107–126

Setyohadi B, Hutagalung EUHU, Frederik Adam JM et al (2014) Summary of the Indonesian guidelines for diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. 27

Orimo H, Nakamura T, Hosoi T, Iki M, Uenishi K, Endo N, Ohta H, Shiraki M, Sugimoto T, Suzuki T, Soen S, Nishizawa Y, Hagino H, Fukunaga M, Fujiwara S (2012) Japanese 2011 guidelines for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis—executive summary. Arch Osteoporos 7:3–20

Yeap SS, Hew FL, Damodaran P, Chee W, Lee JK, Goh EML, Mumtaz M, Lim HH, Chan SP (2016) A summary of the Malaysian Clinical Guidance on the management of postmenopausal and male osteoporosis, 2015. Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia 2(1):1–12

Gilchrist N, Reid IR, Sankaran S, Kim D, Drewry A, Toop L, McClure F (2017) Guidance on the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in New Zealand. Osteoporosis New Zealand, Wellington

Li-Yu J, Perez EC, Canete A, Bonifacio L, Llamado LQ, Martinez R, Lanzon A, Sison M, Osteoporosis Society of Philippines Foundation I, Philippine Orthopedic Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Task Force Committee on O (2011) Consensus statements on osteoporosis diagnosis, prevention, and management in the Philippines. Int J Rheum Dis 14:223–238

Health Insurance Review Agency (2010) General guideline of pharmacologic intervention for osteoporosis. http://www.hira.or.kr. Accessed 26 July 2017

Hwang JS, Chan DC, Chen JF, Cheng TT, Wu CH, Soong YK, Tsai KS, Yang RS (2014) Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in Taiwan: summary. J Bone Miner Metab 32:10–16

Songpatanasilp T, Sritara C, Kittisomprayoonkul W et al (2016) Thai Osteoporosis Foundation (TOPF) position statements on management of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia 2:191–207

Vietnam Rheumatology Association (2012) Diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatments of common rheumatic diseases. Viet Nam Education Publishing House, Hanoi, pp 247–258

Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society (2016) Secondary fracture prevention program initiative: resource 1—secondary fracture prevention program resource pack. Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, Sydney

Wang O, Hu Y, Gong S et al (2015) A survey of outcomes and management of patients post fragility fractures in China. Osteoporos Int 26:2631–2640

Tian M, Gong X, Rath S, Wei J, Yan LL, Lamb SE, Lindley RI, Sherrington C, Willett K, Norton R (2016) Management of hip fractures in older people in Beijing: a retrospective audit and comparison with evidence-based guidelines and practice in the UK. Osteoporos Int 27:677–681

Leung KS, Yuen WF, Ngai WK, Lam CY, Lau TW, Lee KB, Siu KM, Tang N, Wong SH, Cheung WH (2017) How well are we managing fragility hip fractures? A narrative report on the review with the attempt to setup a Fragility Fracture Registry in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 23:264–271

Rath S, Yadav L, Tewari A et al (2017) Management of older adults with hip fractures in India: a mixed methods study of current practice, barriers and facilitators, with recommendations to improve care pathways. Arch Osteoporos 12:55

Hagino H, Sawaguchi T, Endo N, Ito Y, Nakano T, Watanabe Y (2012) The risk of a second hip fracture in patients after their first hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 90:14–21

Baba T, Hagino H, Nonomiya H, Ikuta T, Shoda E, Mogami A, Sawaguchi T, Kaneko K (2015) Inadequate management for secondary fracture prevention in patients with distal radius fracture by trauma surgeons. Osteoporos Int 26:1959–1963

Iba K, Dohke T, Takada J, Sasaki K, Sonoda T, Hanaka M, Miyano S, Yamashita T (2017) Improvement in the rate of inadequate pharmaceutical treatment by orthopaedic surgeons for the prevention of a second fracture over the last 10 years. J Orthop Sci

Yeap SS, Nur Fazirah MFR, Nur Aisyah C, Zahari Sham SY, Samsudin IN, Subashini CT, Hew FL, Lim BP, Siow YS, Chan SP (2017) Trends in post osteoporotic hip fracture care from 2010 to 2014 in a private hospital in Malaysia 3(2):112–116

Braatvedt G, Wilkinson S, Scott M, Mitchell P, Harris R (2017) Fragility fractures at Auckland City Hospital: we can do better. Arch Osteoporos 12:64

Kim SR, Park YG, Kang SY, Nam KW, Park YG, Ha YC (2014) Undertreatment of osteoporosis following hip fractures in jeju cohort study. J Bone Metab 21:263–268

Kim SC, Kim MS, Sanfelix-Gimeno G et al (2015) Use of osteoporosis medications after hospitalization for hip fracture: a cross-national study. Am J Med 128:519–526 e511

Yu YM, Lee JY, Lee E (2017) Access to Anti-osteoporosis Medication after Hip Fracture in Korean Elderly Patients. Maturitas 103:54–59

Jung Y, Ko Y, Kim HY, Ha YC, Lee YK, Kim TY, Choo DS, Jang S (2019) Gender differences in anti-osteoporosis drug treatment after osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Metab 37:134–141

Angthong C, Rodjanawijitkul S, Samart S, Angthong W (2013) Prevalence of bone mineral density testing and osteoporosis management following low- and high-energy fractures. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 47:318–322

Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society (2018) Secondary fracture prevention program initiative. http://www.fragilityfracture.org.au/. Accessed 5 Feb 2018

Kung AW, Fan T, Xu L et al (2013) Factors influencing diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture among postmenopausal women in Asian countries: a retrospective study. BMC Womens Health 13:7

Osteoporosis New Zealand (2012) Bone Care 2020: a systematic approach to hip fracture care and prevention for New Zealand. Wellington

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) Hip fracture: the management of hip fracture in adults. NICE Clinical Guideline 124

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) Steering Group (2014) Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care: improving outcomes in hip fracture management of adults. Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry Steering Group, Sydney