Abstract

Summary

This study sought to determine the association between calcaneal quantitative ultrasound (QUS) and fracture risk in individuals without osteoporosis according to the World Health Organization criteria (i.e., BMD T-score > −2.5). We found that calcaneal QUS is an independent predictor of fracture risk in women with non-osteoporotic bone mineral density (BMD).

Introduction

More than 50 % of women and 70 % of men who sustain a fragility fracture have BMD above the osteoporotic threshold (T-score > −2.5). Calcaneal QUS is associated with fracture risk. This study aimed to test the hypothesis that low calcaneal QUS is associated with increased fracture risk in individuals with non-osteoporotic BMD.

Methods

We included 312 women and 390 men aged 62–90 years with BMD T-score > −2.5 at femoral neck. QUS was measured in broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA) at the calcaneus using a CUBA sonometer. BMD was measured at the femoral neck (FNBMD) by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry using GE Lunar DPX-L densitometer. The incidences of any fragility fracture were ascertained by X-ray reports during the follow-up period from 1994 to 2011.

Results

Of the 702 participants, 26 % of women (n = 80/312) and 14 % of men (n = 53/390) experienced at least one fragility fracture during the follow-up period. In women, after adjusting for covariates, increased risk of any fracture was significantly associated with decreased BUA (HR = 1.50; 95 % CI, 1.13–1.99). Compared with that of FNBMD, the models with BUA, in women, had greater AUC (0.71, 0.85, 0.71 for any, hip and vertebral fracture, respectively), and yielded a net reclassification improvement of 16.4 % (P = 0.009) when combined with FNBMD. In men, BUA was not significantly associated with fracture risk before and after adjustment.

Conclusion

These results suggest that calcaneal BUA is an independent predictor of fracture risk in women with non-osteoporotic BMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fragility fracture is a major health problem in our rapidly aging society and imposes considerable economic burden on the health care system. Approximately one in two women and one in three men aged 60 or over will experience at least one fragility fracture during their remaining lifetime [1]. The associated mortality rates are 37 and 45 % for hip and vertebral fracture, respectively [2]. At present, bone mineral density (BMD) as measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the standard, but imperfect, measure for bone assessment. In 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined osteoporosis as a BMD of 2.5 standard deviation or more below the young female adult mean value as measured by DXA (i.e., T-score ≤ −2.5) [3]. However, a recent study has found that approximately 50 % of women and 70 % of men with fracture occurred with BMD level above the WHO defined osteoporotic range [4]. Although it is well established that clinical factors such as advancing age, history of falls and prior fracture are important contributors to an elevated risk of fragility fracture[5, 6], combining BMD with clinical risk factors did not fully explain the occurrence of fragility fracture in individuals with high BMD [4].

Quantitative ultrasound (QUS), as measured by broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA, in decibels per megahertz) and speed of sound (meters per second), has been suggested to be reflective of both bone density and bone structure [7–9]. Many studies have shown that QUS measurements, particularly those measured at the heel, can predict fracture risk as well, and independent of BMD [10–14]. So far, no data are available as to whether calcaneal QUS is able to predict fracture in individuals with BMD above osteoporotic range. Thus, the present study sought to determine the association between calcaneal QUS and fracture risk in non-osteoporotic men and women according to the WHO criteria.

Study design and methods

Participants

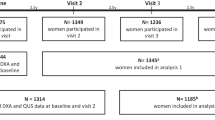

This analysis is part of the ongoing Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study (DOES), a population-based prospective study of the incidence risk factors for fracture and chronic diseases. The DOES project commenced in 1989 at Dubbo, a city of ~32,000 people situated 400 km northwest of Sydney, Australia. The initial study population was comprised of 1,581 men and 2,095 women aged ≥60 years, of whom 98.6 % were Caucasian and 1.4 % were indigenous aboriginal. The study design and details of the population have been described elsewhere [6, 15]. Quantitative ultrasound assessment commenced in 1994. Non-osteoporotic individuals, in this study, referred to those with BMD T-score above −2.5 at femoral neck, according to the WHO definition [3]. After excluding those with malignant and metabolic bone disease, the present study included 312 women and 390 men with BMD T-score > −2.5 who had also undergone QUS assessment at calcaneus. All participants were recruited between 1994 and 2011, aged between 62 and 90 years and had been followed for a median of 12 years (range 0.1–17 years). The study was approved by the St Vincent’s Hospital Ethics committee and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Risk factors assessment and bone measurement

Anthropometric data were obtained by standard methods as described previously [4]. Other clinical risk factors including history of fall, prior fracture, comorbidities, smoking, dietary calcium intake, and physical activity were recorded in a structured questionnaire administered by a trained nurse during the interviews with the participants at initial and subsequent visits at 2-year intervals. Broadband ultrasound (BUA, in decibels per megahertz) and velocity of sound (VOS, in meters per second) were measured at the calcaneus using CUBA sonometer (McCue Ultrasonics, Winchester, UK). The coefficients of variation for BUA and VOS were 3.1 and 0.3 %, respectively [16]. BMD was measured at the femoral neck by DXA, using GE Lunar DPX-L densitometer (Lunar Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The radiation dose used is less than 0.1 μGy and the coefficient of variation for femoral neck BMD was 1.5 % in our institution [4, 17]. Since lumbar spine BMD measurement is susceptible to age-related degenerative changes in older people, we did not consider spinal BMD in the analysis.

Ascertainment of fracture

Fractures were defined as those occurred with minimal trauma such as fall from standing height or less, including any type of fracture. They were further categorized into subgroups of hip and vertebral fractures. Fractures due to high trauma such as motor vehicle accident, sport injury, or fall from above standing height were excluded from the analysis. No systemic X-ray screening for asymptomatic vertebral fractures was conducted prior to the study and vertebral fractures were clinically diagnosed. All fracture cases were ascertained through X-ray reports from two to three radiology centers within the Dubbo region as previously described [18].

Data analysis

The association between BMD and BUA was assessed by the Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficient. The distributions of non-osteoporotic (BMD T-score > −2.5) fracture among different femoral neck BMD and BUA tertile groups were compared based on the cutoff values derived from the general population with both osteoporotic and non-osteoporotic individuals included. Association between fracture risk and BUA or BMD measured at the femoral neck (FNBMD) was assessed by the Cox’s proportional hazards model with or without adjustment for age, falls in the preceding 12 months (at baseline assessment), and prior fracture after age 50. For the model with BUA, further adjustment for FNBMD was performed. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CIs) were estimated per one standard deviation (SD) of measurement, as derived from the entire study population with both osteoporotic and non-osteoporotic subjects included. The ability of BUA and FNBMD model to discriminate between subjects with or without fracture was examined by the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. The discriminatory ability of the model with both BUA and FNBMD combined was further compared with that of FNBMD using the reclassification analysis [19]. In this method, the absolute 10-year risk of fracture was estimated by each of the two models and then classified into three risk groups, i.e., <18, 18–29, and >29 %, and the net reclassification improvement (NRI) was computed. The chosen cutoff value was based on the distribution of the fracture incidence in the study population (i.e., lower tertile and upper tertile), so as to have a comparable sample size among the three groups. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical environment Version 2.13.0 for Windows [20].

Results

Baseline characteristics

Over the 17 years study period, 702 participants with calcaneal QUS were followed for a median of 12 years (range 0.1–17 years, a total of 7,437 persons per years). Overall, 26 % (80/312) of women and 14 % (53/390) of men had sustained at least one fragility fracture during the follow-up period. Clinical vertebral fractures were more common than hip fractures in both men (23 vs 19 % of all fractures) and women (39 vs 15 % of all fractures). In both sexes, those with fracture were significantly older, more likely to have experienced a fall in the preceding 12 months, and had prior fracture after age of 50, compared with their non-fractured counterparts. Men with fracture also had lower body weight than those without fracture (Table 1).

Both BUA and femoral neck BMD measurements were lower in the fracture groups than the non-fractured groups. However, the differences were only statistically significant in women and not in men (Table 1). The correlation between BUA measurements and femoral neck BMD was 0.30 for men and 0.35 for women. There was no significant difference in VOS measurement between fracture and non-fracture individuals. Inclusion of VOS with BUA did not improve the performance of the model, and hence, the measurement was not included in the subsequent analysis.

Distribution of fracture cases

For women with BMD above the osteoporotic range (Fig. 1a), approximately 35 % of the fracture cases had BUA at lower tertile, but only ~16 % lies within the lower tertile of FNBMD measurement. In contrast, ~35 % of the fractures occurred in women with higher tertile FNBMD and ~19 % of them had BUA within the higher tertile. As for men, the distribution of fracture was similar between FNBMD and BUA across different tertile groups (Fig. 1b).

Risk factors for fracture

In women with BMD T-score greater than −2.5, lower BUA was significantly associated with an increased risk of fracture. For each SD decrease in BUA, the risk of fracture was increased by approximately 1.7-fold (95 % CI, 1.33–2.29) (Table 2). After adjustment for age, falls, and prior fracture, BUA remained a significant risk factor of any fracture (HR = 1.50; 95 % CI, 1.13–1.99) and hip fracture (HR = 4.17; 95 % CI, 1.67–10.43), but not vertebral fracture (HR = 1.51; 95 % CI, 0.96–2.38). Adjustment for FNBMD yielded similar results with a HR of 1.47 (95 % CI, 1.10–1.97) for any fracture, 4.24 (95 % CI, 1.57–11.44) for hip fracture, and 1.53 (95 % CI, 0.96–2.46) for vertebral fracture (Table 3). In men, the association between BUA and fracture risk was statistically insignificant before or after adjustment, regardless of the fracture site (Tables 2 and 4). Meanwhile, advancing age, falls, and preexisting fracture were each significantly associated with higher risk of any fracture in both sexes, but FNBMD was not after adjustment for covariates (Tables 3 and 4).

BMD, BUA, and fracture discrimination

The prognostic performance, in terms of its ability to discriminate between fracture and non-fracture individuals with non-osteoporotic BMD, was evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) (Table 5). In women, the model with BUA showed a better discrimination than FNBMD for any fracture (AUC = 0.71 vs 0.68), hip fracture (AUC = 0.85 vs 0.77), and vertebral fracture (AUC = 0.71 vs 0.69). Inclusion of BUA with the FNBMD model resulted in a greater AUC value for any fracture (0.71, P = 0.006) and hip fracture (0.85, P = 0.001), compared with that of the FNBMD model, but not significantly different from that of the BUA model. Reclassification analysis using the combined model yielded a total NRI of 16.4 % (P = 0.009) and 33.8 % (P = 0.04) for any and hip fracture, respectively, but no improvement was noted for vertebral fracture (Table 6).

In men, similar AUC values were observed between FNBMD (AUC = 0.70, 0.74, and 0.73 for any, hip, and vertebral fracture, respectively) and BUA model (AUC = 0.71, 0.68, and 0.72 for any, hip, and vertebral fracture, respectively). No significant improvement was achieved by combining BUA with FNBMD (Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

Although BMD is currently the standard method for bone assessment, it is not a perfect predictor. More than 50 % of women and 70 % of men with fracture do not have BMD below the osteoporotic threshold as defined by the World Health Organization [4]. QUS, particularly those measured at the heel, has been shown to predict fracture risk as well and independent of BMD [10–12] in the general population. In this study, we examined whether calcaneal QUS is also a predictor of fracture risk among people with BMD above the osteoporotic range (BMD T-score > −2.5). Our results suggest that low calcaneal BUA was significantly associated with greater fracture risk in women with BMD T-score above −2.5 at the femoral neck. In addition, a combination of BUA and FNBMD could enhance the accuracy of identifying fracture cases in this group of the population.

The finding is in line with that previously reported by the EPIDOS study for women with higher BMD [21], and the strength of association between BUA and risk of any fracture is comparable to that found in the general female population from a meta-analysis [22]. However, the odds of hip fracture in our study was higher than that found in these two studies [21, 22]. The discrepancy could be caused by the different types of instrument being used, but it is also likely due to the small number of hip fracture in the present study.

Our finding that VOS was not significantly associated with fracture risk is consistent with that previously reported by the EPIC-Norfolk group [23] but inconsistent with the findings of the EPIDOS study[21]. There are many underlying factors that could be accounted for the conflicting results, since Lunar Achilles scanner was used by the EPIDOS study [21] and CUBA sonometer was used in this and the EPIC-Norfolk study [23]. The technological characteristics of the machine may, in part, contribute to the discrepancy observed for the VOS measurements. On the other hand, studies on vertebral and human calcaneal bone had suggested that velocity of ultrasound does not correlate as well as BUA with trabecular thickness in the calcaneus using the CUBA machine [24]. This may further explain the lower fracture predictive value of calcaneal VOS compared to that of BUA.

Furthermore, when VOS and BUA were considered simultaneously in the same model, it did not result in a better model performance. In fact, the overall NRIs were slightly lower in both women (NRI = 12.6 %) and men (NRI = 1.3 %) for risk of any fracture (data not shown). This finding is in line with that reported by the EPIC-Norfolk group in two separate studies [23, 25].

Lower BMD at femoral neck was associated with greater risk of any fracture in women with non-osteoporotic BMD but failed to reach statistical level after adjustment for covariates in either sexes. The insignificant association between femoral neck BMD and fracture risk is, perhaps, not surprising as only individuals with femoral neck BMD above −2.5 were selected for the analysis. Besides, the correlations between BUA and BMD were low in both genders (r = 0.35 for women, r = 0.30 for men), which suggests that the two modalities may not identify the same group of people.

A probable explanation for the stronger association between calcaneal BUA and fracture risk in women with BMD T-score > −2.5 could be attributed to the basic principle behind the technique. In theory, QUS measurement is based on both bone density and bone quality, i.e., microarchitecture and elasticity, which are important determinants of bone strength [26]. Although the currently available data are insufficient to conclude that QUS is a definitive measure of bone quality, there are evidence suggesting that QUS is related to bone elasticity [27, 28] and bone structure [9, 29]. Thus, it is possible that QUS may provide additional information for identifying women who are at-risk of fracture but do not have low BMD.

Our finding also highlights the limitation with the operational definition of osteoporosis proposed by the World Health Organization, which was established largely based on the bone density measurement. An advantage of the WHO definition is that it provides a simple interpretation of BMD data for diagnostic purpose [30]. However, osteoporosis is referred clinically as “a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fractures” [31]. Even though the WHO definition is able to capture the integral component of osteoporosis (i.e., low bone mass), it falls short to address the equally important part of the disease—the deterioration of bone structure or bone quality. The presence of the preexisting low-trauma fracture in our study population at BMD level above −2.5 illustrates the potential of the problem. Moreover, it is not clear as whether the WHO diagnostic threshold is appropriate for use in men as its reference value is derived from the female population only.

In this study, the magnitude of association between BUA and fracture risk was lower in men than in women and did not reach statistical significance. This could be due to the small number of fracture cases in men. The underlying factor is likely related to the cutoff value of BMD T-score being used to define osteoporosis. Since men have larger bone size and higher BMD measurements than women [32], using the same cutoff value to define osteoporosis is likely to classify more men as non-osteoporotic. In fact, when the cutoff value of BMD T-score was increased to −1.0, BUA was found to be significantly associated with greater fracture risk in men (HR = 1.69; 95 % CI, 1.12–2.54, after adjustment, data not shown). Meanwhile, in the EPIC-Norfolk study with a much larger sample of men (n = 6,471), one SD decrease in BUA was associated with 87 % increase in fracture risk. However, in that study, when stratified into different risk groups based on the distribution of the ultrasound measurements, BUA was not significantly associated with fracture risk in those above tenth percentile of the BUA measurement [25]. Taken together, BUA could be useful in the prediction of fracture in men either in the presence or absence of BMD.

The present finding has implication in the individualization of fracture risk and treatment. Currently, treatment decision is largely based on, among others, BMD T-scores ≤ −2.5. However, as more than 50 % of the fracture cases occur in those with T-scores > −2.5, and among these individuals, lower BUA values were associated with increased fracture risk, suggesting that BUA measurement could help identify additional high-risk individuals. In those women with non-osteoporotic BMD, the relative risk of fracture per SD decrease in BUA was 1.50 (95 % CI, 1.13–1.9), which is comparable to a previous estimate for the general population (RR 1.55; 95 % CI, 1.35–1.78) [22]. This suggests that BUA is a BMD-independent predictor of fracture risk. In other words, measurement of QUS could be useful in identifying high-risk individuals who are not identified by BMD alone.

Meanwhile, there is increasing consensus that treatment decision is better determined by absolute risk assessment than by BMD alone. At present, the Garvan fracture risk calculator and fracture risk assessment tool are the two most commonly used models for fracture risk assessment, but neither of them includes QUS measurements. The results of this study suggest that calcaneal BUA could provide additional information, particularly in identification of high-risk women who do not have BMD at the osteoporotic range. For example, a woman aged 70 years old with BMD T-score of −1.5 and no history of falls or prior fracture would had a 10-year absolute risk of approximately 15 % based on the existing Garvan fracture risk model. However, if the same woman had her BUA measurement (i.e., 40 dB/MHz) included, her 10-year absolute risk would increase to 24 %, which could lead to different treatment recommendation.

These findings should be interpreted within the context of strength and limitations. A notable strength of this study is its long duration of follow-up, population-based, and prospective design, which helps minimize potential biases inherent in volunteer-based and cross-sectional studies. However, the sample size was relatively small, which could lead to underestimation of the risk associated with each risk factor. Furthermore, the results found in men and those of hip or vertebral fracture should be interpreted with caution due to the low number of fracture cases. Since the study population was mainly of Caucasian background aged above 60, its findings may not be readily applicable to other populations, particularly those in the younger age groups. In summary, the present study demonstrated that calcaneal BUA is an independent predictor of fracture risk in women with non-osteoporotic BMD, and hence, could enhance fracture prediction at the individual level.

References

Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2007) Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men. J Bone Miner Res 22:781–788

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA (1999) Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 353:878–882

World Health Organization (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. WHO Technical Report Series 843 Geneve

Nguyen ND, Eisman JA, Center JR, Nguyen TV (2007) Risk factors for fracture in nonosteoporotic men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:955–962

Nguyen TV, Center JR, Sambrook P, Eisman JA (2001) Risk factors for proximal humerus, forearm, and wrist fractures in elderly men and women: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Study. Am J Epidemiol 153:587–595

Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Kelly PJ, Sambrook P (1996) Risk factors for osteoporotic fractures in elderly men. Am J Epidemiol 144:255–263

Njeh CF, Hodgskinson R, Currey JD, Langton CM (1996) Orthogonal relationship between ultrasound velocity and material properties of bovine cancelleous bone. Med Eng Phys 18:373–381

Cortet B, Boutry N, Dubios P, Legroux-Gerot I, Cotton A, Marchandise X (2004) Does quantitative ultrasound of bone reflect more bone density than bone microarchitecture. Calcif Tissue Int 74:60–67

Gluer CC, Wu CY, Jergas M, Goldstgein SA, Genant HK (1994) Three quantitative parameters reflect bone structure. Calcif Tissue Int 55:46–52

Bauer DC, Gluer CC, Genant HK, Stone K (1995) Quantitative ultrasound and vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 10:353–357

Diez-Perez A, Gonzalez-Macias J, Marin F, Abizanda M, Alvarez R, Gimeno A, Pegenaute E, Vila J (2007) Prediction of absolute risk of non-spinal fractures using clinical risk factors and heel quantitative ultrasound. Osteoporos Int 18:629–639

Mautalen C, Vega E, Gonzalez D, Carrilero P, Otano A, Silberman F (1995) Ultrasound and dual X-ray absorptiometry densitometry in women with hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 57:165–168

Sakata S, Skushida K, Yamazaki K, Inoue T (1997) Ultrasound bone densitometry of os calcis in elderly Japanese women with hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 60:2–7

Gluer CC (1997) Quantitative ultrasound techniques for the assessment of osteoporosis: expert agreement on current status. J Bone Miner Res 12:1280–1288

Simons LA, McCallum J, Simons J, Powell I, Ruys J, Heller R, Lerba C (1990) The Dubbo study: an Australian prospective community study of the health of elderly. Aust N Z J Med 20:783–789

Zochling J, Nguyen TV, March LM, Sambrook PN (2004) Quantitative ultrasound measurements of bone: measurement error, discordance, and their effects on longitudinal studies. Osteoporos Int 15:619–624

Nguyen TV, Sambrook P, Eisman JA (1997) Sources of variability in bone mineral density measurements: implications for study design and analysis of bone loss. J Bone Miner Res 12:124–135

Jones G, Nguyen TV, Sambrook P, Kelly PJ, Gilbert C, Eisman JA (1994) Symptomatic fracture incidence in elderly men and women: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology study (DOES). Osteoporos Int 4:277–282

Pencina M, D’Agostino RB Sr, D’Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS (2008) Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 27:157–172

R Development Core Team (2006) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <http://wwwRprojectorg>

Robbins JA, Schott AM, Garnero P, Delmas PD, Hans D, Meunier PJ (2005) Risk factors for hip fracture in women with high BMD: EPIDOS study. Osteoporos Int 16:149–154

Marin F, Gonzalez-Macias J, Diez-Perez A, Palma S, Delgado-Rodriguez M (2006) Relationship between bone quantitative ultrasound and fractures: a meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res 21:1126–1135

Moayyeri A, Kaptoge S, Dalzell N, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Bingham S, Reeve J, Khaw KT (2009) The effect of including quantitative heel ultrasound in models for estimation of 10-year absolute risk of fracture. Bone 45:180–184

Trebacz H, Natali A (1999) Ultrasound velocity and attenuation in cancellous bone samples from lumbar vertebrae and calcaneus. Osteoporos Int 9:99–105

Khaw KT, Jonathan R, Luben R, Bingham S, Welch A, Wareham N, Oakes S, Day N (2004) Prediction of total and hip fracture risk in men and women by quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus: EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Lancet 363:197–202

Langton CM, Njeh CF (eds) (2004) The physical measurement of bone. Insitute of Physics, Bristol

van den Bergh JP, van Lenthe GH, Hermus AR, Corstens FH, Smals AG, Huiskes R (2000) Speed of sound reflects Young’s modulus as assessed by microstructural finite element analysis. Bone 26:519–524

Haiat G, Padilla F, Svrcekova M, Chevalier Y, Pahr D, Peyrin F, Laugier P, Zysset P (2009) Relationship between ultrasonic parameters and apparent trabecular bone elastic modulus: a numerical approach. J Biochem 18:2033–2039

Duquette J, Lin J, Hoffman A, Houde J, Ahmadi S, Baran D (1997) Correlations among bone mineral density, broadband ultrasound attenuation, mechanical indentation testing, and bone orientation in bovine femoral neck samples. Calcif Tissue Int 60:181–186

Delmas PD (2000) Do we need to change the WHO definition of osteoporosis? Osteoporos Int 11:189–191

Kanis JA, Gluer CC (2000) An update on the diagnosis and assessment of osteoporosis with densitometry. Osteoporos Int 11:192–202

Gielen E, Vanderschueren D, Callewaert F, Boonen S (2011) Osteoporosis in men. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 25:321–335

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Sr Janet Watters, Donna Reeves, and Shaye Field for the interview, data collection, and measurement of bone mineral density. We also appreciate the invaluable help of the staff of Dubbo Base Hospital. We thank Mr. J. McBride, Dania Mang, and the IT group of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research for the management of the database. The study was partly supported by the Australia National Health and Medical Research Council. N.D.N. is supported by a fellowship from the AMBeR (Australian Medical Bioinformatics Resource). T.V.N. is supported by a senior research fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Conflicts of interest

Professor J.A. Eisman has served as consultant on the Scientific Advisory Board for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and deCode. He was the editor-in-chief for the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research from 2003 to 2007 and was a committee member of Department of Health and Aging, Australian Government and Royal Australasian College of General Practitioners. Dr. Jacqueling R. Center has given educational talks for Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Sanofi-Aventis. Professor T.V. Nguyen has received honorarium for consulting and speaking in symposia sponsored by MSD, Roche, Servier, Sanofi-Aventis, and Novartis. Other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, M.Y., Nguyen, N.D., Center, J.R. et al. Quantitative ultrasound and fracture risk prediction in non-osteoporotic men and women as defined by WHO criteria. Osteoporos Int 24, 1015–1022 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2001-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2001-2