Abstract

Introduction

Fall risk is a major contributor to fracture risk; implementing fall reduction programmes remains a challenge for health professionals and policy-makers.

Materials and methods

We aimed to (1) ascertain whether the care received by 54 older adults after an emergency department (ED) fall presentation met internationally recommended ‘Guideline Care’, and (2) prospectively evaluate this cohort’s 6-month change in fall risk profile. Participants were men and women aged 70 years or older who were discharged back into the community after presenting to an urban university tertiary-care hospital emergency department with a fall-related complaint. American Geriatric Society (AGS) guideline care was documented by post-presentation emergency department chart examination, daily patient diary of falls submitted monthly, patient interview and physician reconciliation where needed. Both at study entry and at a 6-month followup, we measured participants physiological characteristics by Lord’s Physiological Profile Assessment (PPA), functional status, balance confidence, depression, physical activity and other factors.

Results

We found that only 2 of 54 (3.7%) of the fallers who presented to the ED received care consistent with AGS Guidelines. Baseline physiological fall risk scores classified the study population at a 1.7 SD higher risk than a 65-year-old comparison group, and during the 6-month followup period the mean fall-risk score increased significantly (i.e. greater risk of falls) (1.7±1.6 versus 2.2±1.6, p=0.000; 29.5% greater risk of falls). Also, functional ability [100 (15) versus 95 (25), p=0.002], balance confidence [82.5 (44.4) versus 71.3 (58.7), p=0.000] and depression [0 (2) versus 0 (3), p=0.000] all worsened over 6 months. Within 6 months of the index ED visit, five participants had suffered six fall-related fractures.

Discussion

We conclude that this group of community-dwelling fallers, who presented for ED care with a clinical profile suggesting a high risk of further falls and fracture, did not receive Guideline care and worsened in their fall risk profile by 29.5%. This gap in care, at least in one centre, suggests further investigation into alternative approaches to delivering Guideline standard health service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Among seniors, falls constitute a well-recognized public health concern. Falls are the fifth leading cause of death [1], and recent Finnish data suggest that escalating age-adjusted rates of fall-related deaths in men cannot be explained by demographic changes alone [2]. Falls are the primary reason for 40% of nursing home admissions [3]. The pivotal PROFET study [4] showed that a multidisciplinary, geriatrician-led intervention could prevent future falls among seniors who presented to the emergency department with an index fall. These data extended an earlier successful multifactorial intervention in community-dwellers screened for fall risk factors [5]. Not surprisingly then, clinical guidelines recommend medical assessment and intervention for seniors presenting with a fall or fall-related injury [1, 3, 6–9]. Worldwide, many geriatricians subscribe to the collaborative guidelines released jointly by the American Geriatrics Society, the British Geriatrics Society and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (‘AGS Guidelines’) for assessment and management of older people who have fallen [1].

Many seniors who fall attend the Emergency Department (ED) for assessment. Falls comprise between 14 and 40% of presentations to EDs [10, 11]. In 2000, 1.6 million older Americans were treated in EDs for fall-related injuries, and more than 1.2 million did not require admission and were discharged back to community care [12, 13]. The ED is an important contact point between seniors and the medical system the world over [4, 6, 11, 14, 15]. As 70% of patients who present to the ED with a fall are discharged back into the community [16], it would be germane to know whether this discharged population was subsequently referred for outpatient and community assessment and intervention as per the AGS Guidelines [4, 16, 17]. Our retrospective investigation of this question revealed that fewer than 32% of community-dwelling seniors recalled receiving followup care after discharge home from the ED [17]. Although those findings are provocative, a single retrospective study based on patient recall has limited external validity.

To our knowledge, no prospective study has analysed the management and medium-term outcome of older adults who presented with a fall to an ED and were discharged back into the community. This population is large, and the demographic profile of its constituent suggests they are at high risk of loss of independence, future falls and fractures [18–21]. Thus, we aimed to identify whether a consecutively-recruited sample of such patients received evidence-based care (AGS Guidelines) following an ED fall presentation and discharge back into the community. Based on our earlier retrospective study [17], we hypothesized that fewer than 30% of participants seeking medical care for a fall by presenting to the ED would receive one or more components of the best practice AGS Guidelines within 6 months of the ED presentation. Our secondary aim was to describe change in this cohort using a validated measure of fall risk profile [22].

Materials and methods

Participants

One investigator (AS) screened patients and/or charts of all people aged over 70 who presented to the Vancouver Hospital ED with a fall-related complaint until the desired sample size of 54 was achieved (May 15 to August 4 2003). For this index ‘fall-related complaint’, a “fall” was defined as “unintentionally coming to the ground or some lower level other than as a consequence of sustaining a violent blow, falling from a significant height as a result of mechanical failure or sudden onset of paralysis as in a stroke or epileptic seizure” [22]. Falls were subcategorized as causing either serve, moderate or no injury. Severe injury included fracture, loss of consciousness or laceration requiring sutures. Moderate injury included bruising, sprains, lacerations not requiring suture, abrasions or a reduction in physical function for at least 3 days.

To be sure to capture fall-related presentations among patients aged over 70, the investigator checked the mechanism that underpinned the presenting complaint (even if the report seemed initially unrelated to falls; e.g. chest pain, pneumonia). This was done, in descending order of preference, from the ED notes or patient/caregiver interrogation or treating emergency physician interrogation or by telephone with the patient (after she/he had received an appropriate letter).

In addition, the patient needed to have been: able to communicate in English, aged 70–years or older and community-dwelling on Vancouver’s lower mainland within 150 km of Vancouver General Hospital. For entry into the study, the participant needed to have been discharged back into the community from the ED without admission to hospital. We excluded: all residents of nursing homes or extended care facilities, patients with a history of pathology or impairments known to cause falling, including Parkinson’s Disease, stroke and Multiple Sclerosis, and patients with significant cognitive impairment (score <24 on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination) [23].

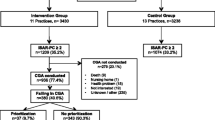

Potential participants were contacted by a researcher (AS) while receiving treatment for their fall at the ED, or by letter and telephone within 10 days of fall presentation. After confirming that the participant met the inclusion criteria for the study, verbal consent was obtained from the participant during the ED encounter or by telephone. All participants provided written consent prior to baseline assessment. Figure 1 outlines the recruitment and interview process for this study, and Figure 2 details the flow of participants through the study (Fig. 2)

.

The study was approved by both the Vancouver Hospital and University of British Columbia Ethics Committees.

Descriptive and independent variables

In-person investigator-administered baseline assessments took place within 1 month of the ED presentation; a similar followup assessment was scheduled 6 months after the ED presentation. Baseline assessment included: patient demographics, circumstances surrounding the fall, emergency physician (EP) management (by patient recall and chart review) as well as fall-related outcome measures, including physiological profile assessment (PPA) and questionnaires as detailed below.

From the ED chart and with patient ratification as required, we noted patient demographics, including age, specific presenting complaint at triage (e.g. wrist fracture), functional status prior to presentation, circumstances of the fall, self-reported medical comorbidities as noted, cognitive function by mini-mental state exam (MMSE) [23], fall history and disposal from the ED. We noted management plans relating to medication rationalization, assessment of postural hypotension, vision assessment and correction where indicated as well as referral for physiotherapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT) and family physician (FP). We noted specific mention of the need for assessment of environmental hazards around the home. We scrutinized charts for the diagnosis/management of osteoporosis and history of fall-related fracture.

In the patient baseline assessment, we systematically enquired about medications and medical conditions using a modification of the Canadian Multi-Centre Osteoporosis Study questionnaire [24] that we have used previously [25, 26]. Physical activity was measured by means of the CORE Questionnaire [27]. We quantified participants’ fear of falling using the 16-item Activities Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Questionnaire [28, 29]. Depression was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [30–32]. We measured daily function using the Barthel Index (BI) [33], which has been used in previous studies of ED fallers [4]. In addition to the ED record of cognitive function, we administered Folstein’s Mini-Mental State Examination [23] as in our previous studies [25, 26].

Dependent variables: physiological profile assessment, falls, medical care and activity

Falls risk score was quantified using the Physiological falls Profile Assessment (PPA) [22] (Prince of Wales Medical Research Institute, Randwick, Sydney, NSW, Australia). The PPA is a valid [27, 34] and reliable [35] instrument for assessing fall risk in older people. Based on the performance of five physiological domains (vision, proprioception, strength, reaction time and balance), the PPA computes a fall risk score (standardized score) for each individual, and this measure has a 75% predictive accuracy for falls in older people [27, 34]. Standardized weightings for each of the five components were derived from a discriminant function for predicting multiple falls from the Randwick Falls and Fractures Study [27]. These weightings (canonical correlation coefficients) were −0.33 for edge contrast sensitivity, 0.20 for lower limb proprioception, −0.16 for isometric quadriceps strength, 0.47 for hand reaction time and 0.51 for postural sway on a compliant foam rubber surface. Fall risk scores below 0 indicate a low risk of falling, scores between 0 and 1 indicate a mild risk of falling, scores between 1 and 2 indicate a moderate risk of falling and scores above 2 indicate a high risk of falling. Table 1 describes the tests from the short-form PPA assessment (Table 1).

During the 6-month longitudinal study, participants completed and returned a Falls, Medical Care and Physical Activity Calendar that was completed daily and submitted monthly. This Calendar documented falls and physical activity as per our previous studies [25, 26] and those of others [5, 36]. In cases where a participant’s recollection or records were unclear or discrepant, a physician (KK) contacted the participant’s family physician to confirm details of medical treatment. In addition, the physician investigator compared the patients self-report of physician management with the GP’s own records in a sample of seven participants who had reported attending the family physician and not receiving care that met any of the Guideline elements.

The 6-month investigator-administered followup assessment repeated all baseline measurements including the PPA and noted the details of management that arose from referrals. Falls were captured using the monthly Falls, Medical Care and Physical Activity Calendar described above. One investigator (AS) also asked the participant whether medical advice for the fall was sought as the result of a referral or of the patient’s own initiative. To provide a comparison for the 6-month change in PPA, we matched the study participants against the control group of another study of community-dwelling people who were identified from a health insurance database (Lord, 2005 #5097). We began with 179 eligible control participants aged >75 years from that study of 620 people detailed elsewhere (Lord, 2005 #5097). We paired those Australian participants against our participants based upon the criteria of baseline PPA score (± 0.2) and age (±2 years).

Analysis

The participant receiving AGS Guideline care at some time during the 6-month followup period was the standard against which the primary outcome of this study was determined. Relative to these Guidelines, each participant’s care was categorized as complete, partial or absent according to the following definitions. Complete Guideline care occurred if, at any time during the 6-month followup period (i.e. not only during the ED presentation), the participant received either (1) a geriatrician assessment or (2) was assessed for fall risk and received a multi-factorial intervention by a health care professional as outlined by the AGS Guidelines. Partial Guideline care occurred if the participant was seen in the ED by a special Geriatric Triage team (nurses with particular training in geriatric issues) or was assessed for fall risk or provided with at least one element of intervention from a health care professional, but not both. No Guideline care occurred when the participant was not provided with any intervention.

Continuous data were examined for outliers (greater than 3 SD above or below the mean) with scatter plots. No outliers were excluded as the purpose of this study was to describe a community-dwelling, older cohort who presented to the ED with a fall. Outliers were consistently seen in the visual components of the PPA (i.e. Edge Contrast Sensitivity and Visual Acuity). Dependant variables were checked for normality by calculating skewness and kurtosis. Descriptive data are reported for all variables of interest [mean (SD), median (IQR) or number (% of total) where appropriate]. Paired t-tests examined the changes in parametric numerical data from baseline to 6 months (PPA Fall Risk Score and components of the PPA, including sway conditions on foam, quadriceps strength, reaction time, proprioception, dorsiflexion strength and visual acuity). Non-parametric data (BI, GDS, ABC and components of the PPA, including sway conditions on the floor, contrast sensitivity and tactile sensitivity) were evaluated using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test with baseline and 6-month data reported by Median (IQR). The level of significance for both tests was set at p≤0.05. The number of falls (by falls diary) and the proportion of fallers and recurrent fallers are reported as descriptive statistics. Also, to seek trends for future research, exploratory analyses were conducted using logistic regression to model the association between baseline PPA and the likelihood of a recurrent fall (yes/no). This provided a regression estimate that shows a change in the odds of a fall for a 1-unit increase in PPA. Significance of the individual regression estimates was tested by Wald statistics (t-tests).

Results

A total of 101 eligible patients presented to the ED, of which 86 were contactable. Of these, 54 (63%) participated and the remainder declined because of the research burden. As per the inclusion criteria, all participants were community-dwelling at baseline (40.7% lived alone and 59.3% lived with at least one adult).

Baseline clinical characteristics and descriptors of the index fall

Baseline characteristics of the 54 participants are presented in Table 2. The mean time between the ED fall presentation (index fall) and the home interview was 13.6 (±4.8) days. The mean age of participants was 78.5 (±5.7) years. In the year prior to the index fall, 19 participants (35%) recalled having fallen another time, and eight (15%) recalled having fallen two or more times previously.

A review of participants’ ED records and self-reports revealed numerous medical comorbidities. One or more cardiovascular disorders that may have contributed to a fall were present in 31 (57%) participants. These conditions included cardiac arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, previous myocardial infarction and postural hypotension. Almost all (n=51, 94%) participants had some form of visual impairment, seven (13%) participants had macular degeneration and 19 (35%) had cataract. Also, 11 (20%) experienced peripheral neuropathy and 27 (50%) had various degrees of osteoarthritis. Osteoporosis was diagnosed in 14 (25.9%) participants (all female), and all but three of these were taking bisphosphonate therapy. In total, 57% of the participants were taking one or more medications that have been associated with increased risk of falling. Twenty-two participants (41%) reported drinking alcohol daily.

Characteristics of the index fall and its treatment are presented in Table 3. The index fall caused severe injury in 50.0% of the cases.

Patient management compared with American geriatrics society Guideline care

Guideline care was provided neither by ED physicians during the index presentation nor by health care professionals during the 6-month followup period. Figure 3 depicts participants’ medical management, including ED discharge instructions and referrals. The most common ED referral was to the participant’s FP (31%) which, in itself, does not constitute Guideline care. When referred to a FP, the patients attended in 82% of cases. No participant reported receiving fall-related assessment during a followup appointment with the FP. That is, there was no report of assessment of balance, strength or vision; nor was there any report of treatment aimed at improving balance, strength or vision. In all seven cases (7 of 51=13.7%) where this self-report was cross-checked with the treating FP, the FP concurred that no element of the fall prevention guidelines had been undertaken.

In total, eight participants received some form of Guideline care during the 6-month followup period. Only two (3.7%) participants received complete Guideline care, and this resulted from ED referral to a geriatrician. Six participants (11%) received partial Guideline care. The Geriatric Triage Team saw these participants in the ED. Partial Guideline care was also provided to two (4%) participants referred from the ED to a cardiologist for investigation of syncope.

Fifteen (28%) participants were discharged from the ED without any further instructions. Of these, three returned to the ED within 24 h of the first ED fall presentation with another fall that required hospital admission. One of these participants experienced the fall while awaiting transport home after discharge from the ED for the index fall.

Six-month followup clinical and functional data, including adverse events

During the 6-month followup, three participants dropped out (one too busy, two died), leaving 51 (94.4%) of the original 54 participants. During the followup period, 10 of 32 (31%) participants who were living with another adult at baseline moved to assisted living facilities.

Over the 6-month observational there was a significant worsening in the Barthel Index (p=0.002), the Geriatric Depression Scale (p=0.004) and the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale (p<0.001) scores. The number of participants involved in weekly physical activity increased from 35.3% to 43.1%.

Seventeen participants (33.3%) reported falling again (subsequent to their index fall), and nine (17.6%) reported multiple falls. Of 34 falls, seven (13.7%) of these resulted in the participant seeking medical attention, with four (7.8%) falls requiring hospital admission.

Five participants (n=5, all female) suffered a fracture as a result of a low trauma fall within 136.7 (±41.8) days (minimum=61 days, maximum=174 days) of the ED fall presentation (two hip fractures, one pelvic fracture, one ankle fracture, two wrist fractures). One participant fell and fractured her wrist 9 days after returning home from the hospital where she had been treated for a fall-related hip fracture. Consequences of the hip and pelvic fractures were death (n=1), relocation to an extended care facility (n=1) or assisted living facility (n=1).

Baseline and change data for the Physiological Profile Assessment (PPA)

Table 4 shows the baseline and 6-month changes for the overall fall risk score (PPA) test and key fall risk score components. At baseline, there was no difference in the mean PPA values of participants who reported at least one fall prior to their ED presentation (index fall) (PPA=1.8±1.7) compared with those who reported that the index fall was their first in 12-months (1.8±1.6).

Over the 6-month followup period, participants’ fall risk profile (SD) increased 29.5% (i.e. greater fall risk) (p=0.000). There was statistically significant deterioration for all components of the Fall Risk Score that contribute to the combined score (postural sway eyes open, foam; quadriceps strength; hand reaction time; proprioception; edge contrast sensitivity) (all, p<0.05).

There was a significant association between the likelihood of a recurrent fall and baseline PPA values (log-likelihood ratio is 53.1, p<0.001 for 1 df). Table 5 shows the odds ratio of the outcome associated with baseline PPA. Recurrent falls were associated with baseline PPA values, as measured by Wald statistics. For every unit of increase in baseline PPA, OR=2.10, [95%CI: 1.3, 3.4].

Discussion

In this study sample, the majority of community-dwelling elderly fallers who presented to a major urban tertiary care hospital ED with a fall, and then were directly discharged home, did not receive any element of the care prescribed by the AGS/BGS/AAOS Guidelines for the prevention of falls for older people. If these findings applied to the broader population from whom the sample was obtained, it would have major clinical and health services implications. Older people who fall contribute a large proportion of the presentations to hospital EDs [10, 38]. Also, having a ‘previous fall’ is a distinct high-risk category in the AGS Guidelines [1] and, thus, should be a catalyst for specific, comprehensive, fall risk factor evaluation. Furthermore, clinical experience would suggest that older people with a previous fall are at a high risk of future serious adverse events, including fracture and head injury [39–43]. Effective preventive measures are available for this population; it would seem that the ED contact should provide an ideal opportunity to initiate elements of the fall prevention Guideline.

Community-dwelling fallers; no Guideline care, high-risk profile for falls and fractures

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effectiveness of AGS Guideline delivery in the ED setting. Our data extend the findings of Baraff and colleagues [6, 15] who investigated fall prevention interventions in one hospital ED. Their study suggested that the ED visit did not lead to preventive measures, but the study was undertaken prior to the publication of Dr. Close’s high-impact PROFET study set in the ED [4] and the subsequent AGS Guideline publication [1]. As the last decade has seen increasing attention to falls as being a major health problem, our a priori hypothesis was that a reasonable proportion of participants in this study would have received Guideline care in 2003 (the time when data were collected).

The widely-held clinical perception that this patient population is at high risk of adverse outcomes is reinforced by our comprehensive descriptive data. The group performed poorly in measures of physiological function associated with the prevention of falls [22], and fractures [19, 44]. At the time of the baseline assessment, these community-dwelling study participants had mean PPA fall risk profiles that indicated they were at higher risk of falling than were a sample of age-matched seniors living in a nursing-home or intermediate-care dwelling [45]. We note that major components of the PPA fall risk profile (quadriceps strength, sway) are also independent risk factors for both fracture [44] and hip fracture [20]. Although we did not measure BMD in our sample, older fallers have previously been shown to have low bone mass [46]. There is a need for evaluation of BMD and fall risk factors in older fallers who present to the ED, as both are risk factors for hip fracture [18, 20].

Our novel longitudinal fall risk profile data raise an important alarm bell, particularly if our findings can be replicated in other ED settings. We note that, on average, participants deteriorated further in their fall risk profile by 0.51 standard deviations (almost 30% worse than at baseline) over 6 months, despite participants having been in contact with the health care system. Thus, our cohort of patients failed to receive Guideline care, and 6 months after a major interaction with the health care system they were at substantially more risk of the same event that brought them initially to the ED. If the risk factors of concern were largely untreatable, such deterioration would be understandable. However, numerous RCTs have proven the effectiveness of interventions that could reduce risk of falls by 40–60% [8].

Our study cohort consisted of only 51 participants who were followed for 6 months; nevertheless, our fall incidence data support the validity of the measures of fall risk profile we report. The cohort of 54 participants experienced 34 falls over 9873 person-days of observation, which translated to 126 falls per 100 person-years. This is similar to 100-person-year rates of 129 falls [4], 114 falls [47] and 94 falls [47, 48] in UK, USA and New Zealand studies, respectively. Taken together, these data indicate that the population of older adults presenting to the ED with a fall are at high risk of recurrent falls. Within 6 months of the index fall presentation, five women suffered six fall-related fractures. There were no fractures among men. This represents an overall fracture rate of 22.2 fractures per 100 person-years. In the study conducted by Close and colleagues [4], the rate of fractures was 9.8 per 100 person-years. Two of the fractures in the present study were hip fractures (n=2), which represents a rate of 11.8 hip fractures per 100 woman-years. This is 44-fold the rate of hip fracture reported in a community-dwelling population of women over the age of 60 [20] (overall rate of hip fracture was 0.8±.057 per 100 woman-years). In the EPIDOS study [18], community-dwelling women had a hip fracture rate of 1.8 per 100 woman-years. We appreciate the caution that is essential when comparing our fracture and hip fracture data with those found in large epidemiological studies, but these clinically-relevant findings point to the validity of the falls risk profile data we collected. As all fractures were among women, our data focus particular clinical relevance to implementing improved care for that group.

Our finding that participants did not receive Guideline care begs the question – ‘Why was this the case?’. Our study was not designed to answer that as a primary research question, but the finding is in keeping with a ‘gap in care’ reported in relation falls management [49] and for many medical conditions [50–53]. There are challenges in obtaining relevant medical information when patients present to the ED [54]. Our data are important because system change tends to address disease-specific ‘gaps in care’. In most cases, decision-makers do not extrapolate data showing that there are limitations in the management of one condition (e.g. asthma) to another condition (e.g. falls in the ED). We understand that in the USA, there is a billing incentive for FPs to undertake a fall risk assessment and, where appropriate, to act on it. To our knowledge, this recent USA health services intervention has not been tested for effectiveness.

Patient awareness of risk can contribute to an improved management of chronic conditions. A simple patient letter improved osteoporosis management after fracture more than threefold [55, 56]. Many patients still attribute falls to ‘accidents’. The AGS Guidelines advocate educating patients [1]. It appears that patients are not aware that most of the factors that cause falls are modifiable. The danger of falls is not only the outcome of the fall (i.e. injury), but the increased risk for subsequent falls and fall-related injury (i.e. hip fracture or death). Qualitative researchers could help investigate why clinicians and patients fail to address neither the fall nor the underlying mechanism of the fall.

Although our study provides a very clear indication that participants did not receive Guideline care, these data must be interpreted with caution. In particular, our findings should not be generalized inappropriately. One limitation of our study was that the sample was only 54 people. Nevertheless, the sampling method was rigorous (24-h recruitment), we recruited a reasonably high proportion of eligible participants and we achieved 94% retention at the 6-month followup. Adding to the validity of our study we note that fall and fracture rates were consistent with those found in a much larger study (PROFET) [4] undertaken in a similar setting in advance of the AGS Guidelines being published. Given the absence of care and the high falls and fracture rates we observed, it would be unethical to undertake an identical observational study with a larger cohort or for a longer followup period in order to ‘increase the numbers’ in this study.

A second limitation is that our data represent findings in one urban tertiary care ED in Canada. As the study is novel, it raises important questions for those responsible for ED care of older fallers. To our knowledge, there are no published data suggesting that Guideline care for older fallers is being implemented. Our hospital ED is an academic centre, with regular ‘Grand Rounds’ which have focused on the issue of falls care at least once annually in both the ED and the Family Practice Rounds. In Canada, falls care has been a regular item in the medical journals that are sent to all physicians. Our own province launched a major ‘Falls Prevention Report’ prior to the study period. The present findings occur against this background of public health and physician ‘education’ on the subject of falls prevention.

Because falls assessment and prevention is demanding, dedicated falls and osteoporosis clinics exist in many countries [57–61]. It warrants investigation whether such ‘fall prevention programmes’ provide fall-reduction. Although a previous Canadian RCT showed that a consultative type of programme reduced the occurrence of multiple falls among previous fallers [62], not all interventions that aim to reduce falls do so [63], and one intervention among institutionalized fallers actually increased falls among the intervention group [64]. To our knowledge, there have been no RCTs of falls clinic service delivery. Such a study would need to test cost-effectiveness as well as clinical outcomes such as falls and, ideally, fractures. Multidisciplinary care models have been delivered in conditions as varied as back pain [65] and management of stroke [66]. Such programmes have only rarely been tested with randomized controlled trials [67].

Another limitation to generalizability of our findings is that data were obtained within the unique Canadian health care system. In our province, for example, few patients have third-party payers for physiotherapy. Strength and balance training is a core, evidence-based element of Guideline care for fallers [8, 37, 68]. We are aware that in the British National Health System system, fallers have free access to physical therapy upon physician referral after a fall [69]. Nevertheless, the geographic and health-care system-specific nature of falls delivery needs to be researched, and the guidelines themselves underscore that research should be undertaken in different health care settings [1].

Summary

Our prospective study of 54 community-dwelling seniors who presented to the ED with a fall, and were not admitted to hospital, demonstrates that the comprehensive geriatric, or FP assessment, had largely not been administered within 6 months of the ED presentation. It is understandable that this would not be provided in the setting of the ED itself, and our results highlight the challenges of Guideline care when it is complicated by issues of continuity of care. At a broader health services level, our study adds to the body of evidence that Guideline development alone does not equal Guideline adoption.

These data provide an important lever for those aiming to deliver integrated health care, and for future research into cost-effective delivery of Guideline care. Mary Tinetti, the doyen of USA geriatric care, has stated that ‘there remains a great disconnect between the wealth of evidence supporting fall prevention efforts and real-world practice’. She continues that ‘there is no simple mechanism in our fragmented, disease-oriented healthcare system for referring individuals to the relevant professionals…’. Our descriptive study provides novel Canadian data that underscore the importance of the ED as a location for identifying high-risk fallers. We conclude that there may be a substantial ‘gap in care’ for community-dwelling older fallers who are discharged home after presenting to the ED department; our findings call for novel methods of translating the knowledge that falls and fractures can be prevented. At present, the benefits of numerous large trials are not being implemented for those who are at high risk and are already actively seeking medical attention.

References

American Geriatrics Society British Geriatrics Society American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention (2001) Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:664–672

Kannus P, Parkkari J, Niemi S, Palvanen M (2005) Fall-induced deaths among elderly people. Am J Public Health 95:422–424

Bezon J, Echevarria KH, Smith GB (1999) Nursing outcome indicator: preventing falls for elderly people. Outcomes Manag Nurs Pract 3:112–6; quiz 6–7

Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C (1999) Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 353:93–97

Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, et al (1994) A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med 331:821–827

Baraff LJ, Penna RD, Williams N, Sanders A (1997) Practice guideline for the ED management of falls in community-dwelling elderly persons. Ann Emerg Med 30:480–489

Feder G, Cryer C, Donovan S, Carter Y (2000) Guidelines for the prevention of falls in people over 65. The Guidelines’ Development Group. Br Med J 321:1007–1011

Cochrane Bone Joint and Muscle Trauma Group, Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, et al (2005) Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people [Systematic Review]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2

Cochrane Injuries Group, McClure R, Turner C, Peel N, Spinks A, Eakin E, et al (2005) Population-based interventions for the prevention of fall-related injuries in older people [Systematic Review]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2

Davies AJ, Kenny RA (1996) Falls presenting to the accident and emergency department: types of presentation and risk factor profile. Age Ageing 25:362–366

Bell AJ, Talbot-Stern JK, Hennessy A (2000) Characteristics and outcomes of older patients presenting to the emergency department after a fall: a retrospective analysis. Med J Aust 173:179–182

Becker C, Kron M, Lindemann U, Sturm E, Eichner B, Walter-Jung B, et al (2003) Effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention on falls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:306–313

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2003) Falls and hip fractures among older adults. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, Ga

Kenny RA, O’Shea D, Walker HF (2002) Impact of a dedicated syncope and falls facility for older adults on emergency beds. Age Ageing 31:272–275

Baraff LJ, Lee TJ, Kader S, Penna RD (1999) Effect of a practice guideline on the process of emergency department care of falls in elder patients. Acad Emerg Med 6:1216–1223

Rowland K, Maitra AK, Richardson DA, Hudson K, Woodhouse KW (1990) The discharge of elderly patients from an accident and emergency department: functional changes and risk of readmission. Age Ageing 19:415–418

Donaldson MG, Khan KM, Davis JC, Salter AE, Buchanan J, McKnight D, et al (2005) Emergency department fall-related presentations do not trigger fall risk assessment: a gap in care of high-risk outpatient fallers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 41: 311–317

Dargent-Molina P, Favier F, Grandjean H, Baudoin C, Schott AM, Hausherr E, et al (1996) Fall-related factors and risk of hip fracture: the EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet 348:145–149

Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, et al (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med 332:767–773

Chang KP, Center JR, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA (2004) Incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures in elderly men and women: Dubbo osteoporosis epidemiology study. J Bone Miner Res 19:532–536

Kaptoge S, Benevolenskaya LI, Bhalla AK, Cannata JB, Boonen S, Falch JA, et al (2005) Low BMD is less predictive than reported falls for future limb fractures in women across Europe: results from the European Prospective Osteoporosis Study. Bone 36:387–398

Lord SR, Menz HB, Tiedemann A (2003) A physiological profile approach to falls risk assessment and prevention. Phys Ther 83:237–252

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) ‘Mini-mental state’: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198

Krieger N, Tenenhouse A, Joseph L, Mackenzie M, Poliquin S, Brown J (1999) The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS): background, rationale, methods. Can J Aging 18:376–387

Carter ND, Khan KM, McKay HA, Petit MA, Waterman C, Heinonen A, et al (2002) Community-based exercise program reduces risk factors for falls in 65- to 75-year-old women with osteoporosis: randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 167:997–1004

Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, J JE, Janssen PA, Lord SR, McKay HA (2004) Resistance and agility training reduce fall risk in women aged 75 to 85 with low bone mass: a 6-month randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 52:657–665

Lord SR, Ward JA, Williams P, Anstey KJ (1994) Physiological factors associated with falls in older community-dwelling women. J Am Geriatr Soc 42:1110–1117

Myers AM, Powell LE, Maki BE, Holliday PJ, Brawley LR, Sherk W (1996) Psychological indicators of balance confidence: relationship to actual and perceived abilities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 51:M37–M43

Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Lord S, McKay HA (2004) Balance Confidence Improves with Resistance or Agility Training: increase is not correlated with objective changes in fall risk and physical abilities. Gerontology 50:373–82

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al (1982) Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 17:37–49

Yesavage JA (1988) Geriatric depression scale. Psychopharmacol Bull 24:709–711

Hyer L, Blount J (1984) Concurrent and discriminant validities of the geriatric depression scale with older psychiatric inpatients. Psychol Rep 54:611–616

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J 14:61–65

Lord SR, Clark RD, Webster IW (1991) Physiological factors associated with falls in an elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc 39:1194–1200

Lord SR, Castell S (1994) The effect of a physical activity program on balance, strength, neuromuscular control and reaction time in older persons. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 75:648–652

Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM (1999) Falls prevention over 2 years: a randomized controlled trial in women 80 years and older. Age Ageing 28:513–518

Barnett A, Smith B, Lord SR, Williams M, Baumand A (2003) Community-based group exercise improves balance and reduces falls in at-risk older people: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 32:407–414

Shaw FE, Bond J, Richardson DA, Dawson P, Steen IN, McKeith IG, et al (2003) Multifactorial intervention after a fall in older people with cognitive impairment and dementia presenting to the accident and emergency department: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 326:73

Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Kidd S, Black D (1991) Risk factors for injurious falls. A prospective study. J Gerontol 46:M164–M170

O’Loughlin JL, Robitaille Y, Boivin JF, Suissa S (1993) Incidence of and risk factors for falls and injurious falls among the community-dwelling elderly. Am J Epidemiol 137:342–354

Koski K, Luukinen H, Laippala P, Kivela S-L (1998) Risk factors for major injurious falls among the home-dwelling elderly by functional abilities. Gerontology 44:232–238

Lord SR, McLean D, Stathers G (1992) Physiological factors associated with injurious falls in older people living in the community. Gerontology 38:338–346

Malmivaara A, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, Reunanen A, Aromaa A (1993) Risk factors for injurious falls leading to hospitalization or death in a cohort of 19,500 adults. Am J Epidemiol 138:384–394

Nguyen TV, Sambrook PN, Kelly PJ, Jones G, Lord S, Freund J, et al (1993) Prediction of osteoporotic fractures by postural instability and bone density. Br Med J 307:1111–1115

Lord SR, March LM, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, Schwarz J, Zochling J, et al (2003) Differing risk factors for falls in nursing home and intermediate-care residents who can and cannot stand unaided. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:1645–1650

Newton JL, Kenny RA, Frearson R, Francis RM (2003) A prospective evaluation of bone mineral density measurement in females who have fallen. Age Ageing 32:497–502

Robertson MC, Devlin N, Gardner MM, Campbell AJ (2001) Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls. 1: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 322:697–701

Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Devlin N, McGee R, Campbell AJ (2001) Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls. 2: controlled trial in multiple centres. Br Med J 322:701–704

Rubenstein LZ, Powers CM, MacLean CH (2001) Quality indicators for the management and prevention of falls and mobility problems in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med 135:686–693

Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, Heywood JT (2005) Adherence to heart failure quality-of-care indicators in US hospitals: analysis of the ADHERE Registry. Arch Intern Med 165:1469–1477

Reuben DB, Roth C, Kamberg C, Wenger NS (2003) Restructuring primary care practices to manage geriatric syndromes: the ACOVE-2 intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:1787–1793

Juby AG, De Geus-Wenceslau CM (2002) Evaluation of osteoporosis treatment in seniors after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 13:205–210

Hajcsar EE, Hawker G, Bogoch ER (2000) Investigation and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with fragility fractures. Can Med Assoc J 163:819–822

Stiell A, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, van Walraven C (2003) Prevalence of information gaps in the emergency department and the effect on patient outcomes. Can Med Assoc J 169:1023–1028

Ashe M, Khan K, Guy P, Kruse K, Hughes K, O’Brien P, et al (2004) Wristwatch-distal radial fracture as a marker for osteoporosis investigation: a controlled trial of patient education and a physician alerting system. J Hand Ther 17:324–328

Majumdar SR, Rowe BH, Folk D, Johnson JA, Holroyd BH, Morrish DW, et al (2004) A controlled trial to increase detection and treatment of osteoporosis in older patients with a wrist fracture. Ann Intern Med 141:366–373

Houghton S, Birks V, Whitehead CH, Crotty M (2004) Experience of a falls and injuries risk assessment clinic. Aust Health Rev 28:374–381

Hill K, Smith R, Schwarz J (2001) Falls Clinics in Australia: a survey of current practice, and recommendations for future development. Aust Health Rev 24:163–174

Nyberg L, Gustafson Y, Janson A, Sandman PO, Eriksson S (1997) Incidence of falls in three different types of geriatric care. A Swedish prospective study. Scand J Soc Med 25:8–13

Dey AB, Bexton RS, Tyman MM, Charles RG, Kenny RA (1997) The impact of a dedicated “syncope and falls” clinic on pacing practice in northeastern England. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 20:815–817

Hill KD, Dwyer JM, Schwarz JA, Helme RD (1994) A falls and balance clinic for the elderly. Physiother Can 46:20–27

Hogan DB, MacDonald FA, Betts J, Bricker S, Ebly EM, Delarue B, et al (2001) A randomized controlled trial of a community-based falls consultation team. Can Med Assoc J 165:537–543

Lord SR, Tiedemann A, Chapman K, Munro B, Murray SM, Sherrington C (2005) The effect of an individualized fall prevention program on fall risk and falls in older people: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:1296–1304

Kerse N, Butler M, Robinson E, Todd M (2004) Fall prevention in residential care: a cluster, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 52:524–531

Rae SA, Blood Smyth J, Ivens M, Penney C (1998) Designing a Back Management Service: the Exeter experience and first year results. Clin Rehabil 12:354–361

Karunaratne PM, Norris CA, Syme PD (1999) Analysis of six months’ referrals to a “one-stop” neurovascular clinic in a district general hospital: implications for purchasers of a stroke service. Health Bull (Edinb) 57:17–28

Naglie G, Tansey C, Kirkland JL, Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Detsky AS, Etchells E, et al (2002) Interdisciplinary inpatient care for elderly people with hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 167:25–32

Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Gardner MM, Devlin N (2002) Preventing injuries in older people by preventing falls: a meta- analysis of individual-level data. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:905–911

Close J (2000) PROFET – improved clinical outcomes at no additional cost. Age Ageing 29:S1:48

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute Interdisciplinary Research Grant (2002). Allison Salter was an NSERC scholar; Karim Khan and Meghan Donaldson carry Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator and Doctoral Trainee Awards, respectively. Riyad Abu-Laban and Heather McKay are Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Career Scholars. Stephen Lord is an Australian NHMRC Principal Research Fellow. Operating funds for this study came from a CIHR interdisciplinary teams enchancement (ICE-IMHA) grant and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Infrastructure Units (Oxland, PI) grant. Doug McKnight provided expert clinical and research mentorship for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salter, A.E., Khan, K.M., Donaldson, M.G. et al. Community-dwelling seniors who present to the emergency department with a fall do not receive Guideline care and their fall risk profile worsens significantly: a 6-month prospective study. Osteoporos Int 17, 672–683 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-0032-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-0032-7