Abstract

This committee opinion reviews the laser-based vaginal devices for treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, vaginal laxity, and stress urinary incontinence. The United States Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning for unsubstantiated advertising and use of energy-based devices. Well-designed case–control studies are required to further investigate the potential benefits, harm, and efficacy of laser therapy in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause, vaginal laxity, and stress urinary incontinence. The therapeutic advantages of nonsurgical laser-based devices in urogynecology can only be recommended after robust clinical trials have demonstrated their long-term complication profile, safety, and efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rationale for the committee opinion

In recent years, in-office treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) and vaginal laxity (VL) using nonsurgical laser-based vaginal devices (LBD) have been introduced worldwide and have been rapidly promoted as both safe and efficacious. LBD within the context of this committee opinion include light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation (LASER). By heating the connective tissue of the vaginal wall to 40–42 °C, these devices induce collagen contraction, neocollagenesis, vascularization, and growth factor infiltration that ultimately revitalize and restore elasticity and moisture to the vaginal epithelium [1]. Intravaginal LBD therapy, which can be expensive, is a widely marketed option among providers for the treatment of urogynecological disorders.

On 30 July 2018, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning against the use of energy-based devices (EBDs), including laser and radiofrequency devices (460 kHz), to perform vaginal rejuvenation or vaginal cosmetic procedures [2]. The purpose of that communication was to alert patients and healthcare providers that the use of EBDs to perform vaginal rejuvenation, cosmetic vaginal procedures, or nonsurgical vaginal procedures to treat symptoms related to menopause, urinary incontinence (UI), or sexual function, may be associated with serious adverse events. The safety and efficacy of EBD for treatment of these conditions has not been established. Vaginal rejuvenation is an ill-defined term; however, it is sometimes used to describe both surgical and nonsurgical procedures intended to treat vaginal symptoms and/or conditions including, but not limited to, vaginal laxity, atrophy, dryness, or itching; pain during sexual intercourse and/or urination; and decreased sexual sensation. The FDA further stated: “...we have not cleared or approved for marketing any EBD to treat these symptoms or conditions, or any symptoms related to menopause, urinary incontinence, or sexual function. The treatment of these symptoms or conditions by applying energy-based therapies to the vagina may lead to serious adverse events, including vaginal burns, scarring, pain during sexual intercourse, and recurring/chronic pain.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists defines vaginal rejuvenation and cosmetic procedures as including designer vaginoplasty, revirgination, other cosmetic vaginal procedures, and G-spot amplification (injection of collagen into the front wall of the vagina) [3]. These elective procedures are generally performed without a clear medical purpose, which is an important factor when considering the risks and benefits of an EBD procedure. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons advocates the use of radiofrequency or laser energy to induce collagen tightening for nonsurgical vaginal rejuvenation [4]. Most women who undergo the laser treatment may report itching, burning, redness, or swelling immediately following the procedure. These side effects do not last more than a few days. There is limited data on long-term safety and complications associated with the treatment. As such, the FDA warning protests the wide-spread use of laser devices without scientific evidence for various indications and the use of false advertising for nonapproved pathologies.

The development of this document occured during November 2017–October 2018, before the FDA warning, and spanned two International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) research and development committees. As such, committee opinion published herein was not rushed to production as a response to the FDA warning but was deliberately and methodically created after the committee reviewed all scientific evidence and conferred with the experts because of the same concerns that prompted the FDA to issue a warning. The committee members were volunteers assigned by the IUGA board. All members who contributed significantly to the 2017 and 2018 committees are credited as authors. The committee opinion paper was overseen by the board liaison, and the final version was approved by the IUGA board for publication.

In this committee opinion, we aim to explore evidence for the use of intravaginal LBD treatment for GSM, VL, and SUI. Intravaginal LBD treatments are performed on an outpatient or day-surgery basis and paid for mainly by the patient, with costs that vary by location and provider. As an exception, in some countries with public/national health service (NHS) funding, patients may not have to pay; regardless, therapies that lack robust evidence should not be routinely recommended to patients. For the purposes of this committee opinion, we concentrate on CO2 and Er:YAG (2940 nm) minimally ablative fractional laser therapies, since there are numerous peer-reviewed studies about these therapies. Nonlaser EBD is not discussed.

Introduction

Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) is a chronic, distressing condition affecting approximately half of postmenopausal women, with significant impact on Quality of life (QoL) [5]. It is mostly manifested—as reported by 70% of affected women—by vaginal dryness [5]. In 2013, the term genitourinary syndrome of menopause was jointly adopted by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). This is a more descriptive term than the term VVA. GSM includes a variety of symptoms and signs associated with a decrease in estrogen and other sex steroids resulting in changes to the lower genital tract [6]. These include dryness, burning, irritation, discomfort, or pain. which may affect coital and sexual activity. GSM may also encompass symptoms on the bladder and pelvic floor arising from the effect of aging and other processes, such as stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI).

VL is a symptom that is poorly characterized and insufficiently explored. The association of VL with symptoms and signs of pelvic floor dysfunction are not established, and most studies have focused on treatment modalities rather than understanding its pathophysiology and establishing better diagnostic tools that could lead to improved preventive and therapeutic modalities [7, 8]. VL is defined by the IUCA/ICS as the complaint of excessive vaginal looseness [9]. Whether VL is a symptom exclusively related to sexual activity is not clear.

While GSM is a condition peculiar to menopause and older women, VL is encountered across all age groups [10]. The prevalence of bothersome VL is variable across studies, at between 2% and 48% [11, 12]. This wide range could represent age, ethnic, cultural, and psychological factors in regard to body image differences. More importantly, it may reflect whether symptom reporting was solicited, volunteered as a chief complaint, or alluded to as a male-partner-driven condition [10]. Nevertheless, the true incidence of VL is unknown [10, 13].

Laser machines, which have long been used to treat a variety of gynecological conditions such as cervical/vaginal dysplasia and Lichen sclerosis, are now marketed under different settings for the treatment of GSM and VL. Number and duration of treatment sessions and maintenance regimens remain largely arbitrary for both CO2 and Er:YAG minimally ablative fractional laser therapies [14]. Although data from histological studies and outcomes from limited clinical trials (expert opinion, case series, nonrandomized prospective cohorts) have been encouraging, the nature (quality) and preponderance (quantity) of available evidence does not go beyond the early investigative phase [15, 16]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for guidance—or, at least, a well-founded opinion within the limits of the currently available evidence—from professional medical organizations regarding the relevance of using EBD technologies. Such opinion would address treatment efficacy of such devices compared with other treatment modalities and identify potential side effects in the short- and long term.

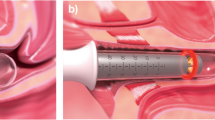

Laser modalities and technique

There are two main types of vaginal lasers: the ablative CO2 and the nonablative Erbium Yag. Both lasers aim to achieve collagen remodeling of the subepithelial connective tissue /fascia but by different mechanisms. Erbium Yag has 10–15 times the affinity for water absorption compared with the CO2 at a wavelength of 10,600 nm and enables a deeper secondary thermal effect and controlled heating of the target mucous membrane of the vaginal wall. This allows controlled heating of the subepithelial layer without burning the vaginal epithelium to promote collagen fiber shrinkage and remodeling [17]. On the other hand, CO2 lasers (10.600 nm) cause tissue denaturation and subsequent collagen- and elastin-fiber remodeling [15]. There is histological evidence for collagen remodeling after both types of laser therapy [18, 19].

Laser resurfacing was introduced in the 1980s with continuous-wave CO2 lasers; however, because of a high rate of side effects, including scarring and prolonged 2-week recovery time, alternate laser technologies were developed. These include short-pulse, high-peak power and rapidly scanned, focused-beam CO2 lasers and normal-mode erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet lasers, which remove skin in a precisely controlled manner. More recently, fractional resurfacing laser technology was developed to minimize risk and shorten recovery times. Nonablative resurfacing produces dermal thermal injury to improve skin wrinkles and photo damage while preserving the epidermis. Fractional resurfacing thermally ablates microscopic columns of epidermal and dermal tissue in regularly spaced arrays over a fraction of the skin surface. This intermediate approach increases efficacy compared with nonablative resurfacing and with faster recovery compared with ablative resurfacing. Neither nonablative nor fractional resurfacing produce results comparable with ablative-laser skin resurfacing, but both have become much more popular than the latter because the risks of treatment are limited, even though outcome measures may be vague depending on patient pathology. Comparative data pertaining to what various laser technologies mean functionally for vaginal use are limited [20].

Typically for both CO2 and Er:YAG lasers, an episode consists of three short procedures of 5–10 min at intervals of 4–6 weeks. A topical anesthetic cream may be applied prior to treatment, although the procedure is well tolerated with minimal discomfort in most cases. The postcare instructions generally caution about redness and/or swelling and discomfort in the treatment area. Intercourse can be resumed within a week after the procedure. There is no evidence-based methodology on how or why a particular treatment sequence is chosen [17].

Efficacy and safety of laser therapy in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause

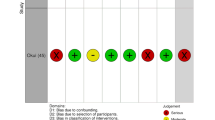

PubMed and EMBASE were searched in May 2018 for publications written in English, with keywords including genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), vulvovaginal atrophy, and laser therapy. The search identified 94 articles, of which 18 were eligible and 76 were rejected based on available full text evaluation, title, and abstract. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklists (JBI) were used to evaluate study design for quality of evidence and risk of bias: eight studies fulfilled the criterion of good quality. Only one randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial was published; therefore, one RCT and seven observational studies were included. No adverse events were reported, and no procedure needed to be stopped because of patient pain or intolerance. Due to their being only one RCT, no meta-analysis could be performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

In all observational studies, the treatment protocol involved three treatment sessions 4–6 weeks apart. In all but two studies, GSM symptoms were assessed by using the visual analog scale (VAS) 0–10 [21,22,23,24]; one study used VAS 0–3. In all relevant studies, GSM symptoms decreased up to the end of follow-up. Reduction of dyspareunia and dryness were significant up to 18 months [22, 25]. After 2 years, 84% experienced improvement in GSM symptoms [26]. However, Pieralli et al. reported a decline in patient satisfaction between 18 and 24 months [27]. Sexual function, including the Vaginal Health Index (VHI), Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and Maturation Index (MI), was assessed in five studies [21,22,23,24,25]. All relevant studies presented a significant increase in sexual function [21,22,23,24,25].

Results of the observational studies (limitations of which include small sample size and absence of a control group) are supported by the only available well-designed RCT, conducted by Cruz et al. [28]. In that study, participants were randomized to one of three treatment arms: laser + estriol treatment (LE), laser + placebo treatment (L), and estriol + sham laser treatment (E). Fractional CO2 laser or sham laser treatment was given in two sessions 4 weeks apart in combination with 20 consecutive weeks of estriol or placebo three times a week. After 20 weeks, the L and LE group presented significant improvement in all examined GSM symptoms: burning, dryness, and dyspareunia. Regarding sexual function, VHI improved significantly in all treatment arms. At 20 weeks’ follow-up, no difference was found between all treatment arms in the full-scale FSFI score, but only the LE group also significantly improved in three individual domains: pain, lubrication, and desire. Meanwhile, an increase of pain was measured in the L group.

Review of collated evidence from these studies to date suggests that laser therapy may be effective in the treatment of GSM and shows no adverse effects. Gasper et al. reported an 18-month follow-up of Erb:Yag + estriol vs. estriol alone in which histological examination showed changes in tropism of the vaginal mucosa and angiogenesis, congestion, and restructuring of the lamina propria in the laser group. Side effects were minimal and of transient nature in both groups, affecting 4% of patients in the laser group and 12% in the estriol group [25]. The only available well-designed RCT indicates that fractional CO2 laser effects are similar to topical estriol and that the combination of fractional CO2 laser and local estrogen might be advantageous [28]. There is not enough evidence to conclude that estrogen be added to all patients receiving laser therapy. Larger RCTs evaluating long-term effects of fractional CO2 laser treatment are required to further investigate its potential harm and efficacy in the treatment of GSM symptoms.

Similar technologies may have been used in plastic surgery on skin and facial tissues, but the potential for adverse effects when used on vulvovaginal tissues needs to be further studied and elucidated, possibly in a postapproval registry. A multicenter study—the Vaginal Erbium Laser Academy Study (VELAS) [29]—using the Er:YAG laser is currently running, but it has no control group and is more of a registry-based study. Studies comparing this new and expensive procedure with the gold standard treatment involving low-dose local hormones, moisturizers, and the new selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) treatment, are also warranted.

In May 2017, Arunkalaivanan et al. conducted a well-designed systematic review of laser therapy as a treatment modality for the relief of symptoms of GSM [17]. They concluded that laser therapy is effective in the short term. The lack of RCTs made it difficult to undertake a meta-analysis. There is insufficient evidence on the long-term effects, including safety and success. Limitations of the study include a small sample size, no long-term follow-up, and lack of active comparator groups. Another study suggests that the effects of Er:YAG laser treatment are independent of any pretreatment, suggesting that it may be proposed for treating postmenopausal women who cannot be treated with hormones (e.g., breast cancer survivors) [30]. An important limitation of these short-term studies is that the potential risks of long-term complications, such as scarring, were not addressed. In all studies reviewed, patients were not monitored for concurrent use of intravaginal products or systemic medications that could have affected vaginal and vulvar health.

Efficacy and safety of laser therapy in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence

The rationale for laser therapy in SUI is to strengthen the suburethral and pubocervical fibromuscularis along with their surrounding fascial supports. There are fewer studies assessing the safety and efficacy of vaginal laser in treating SUI alone than for GSM. Some studies included urinary symptoms (and SUI) as part of the symptom complex of GSM. There are many manufacturers of LBD systems, and an online search of PubMed and EMBASE in May 2018 for publications written in English, with keywords including stress urinary incontinence and laser therapy found no evidence-based papers assessing safety or efficacy. As such, they have not been individually described in this document. There are no papers to date comparing CO2 or Erbium Yag lasers for treating SUI with standard of care or traditional surgeries. However, an RCT comparing their efficacy in GSM has been registered [31].

There is mixed objective evidence in the literature to support the use of LBD in treating SUI. The most commonly used outcome measure is the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI-SF) [18, 21, 30, 32,33,34,35,36,37]. The duration of follow-up also varies significantly; however, the predominant follow-up duration is 6 months. The papers discussed now are either observational cohort studies or case series. Pitsouni et al. noted an improvement in ICIQ-UI-SF, the King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ), and Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) scores 1 month after CO2 laser therapy [21]. Gonzalez et al. showed a similar improvement in ICIQ-UI-SF scores, along with a sustained reduction in 1-h pad weights at 12, 24, and 36 months following CO2 laser therapy for SUI [18].

More studies have assessed Erbium Yag therapy for SUI compared with CO2 laser. Most have a 6-month follow-up and predominantly subjective assessment of efficacy, mainly using the ICIQ-UI-SF questionnaire [30, 32,33,34,35,36, 38, 39]. Six papers analyzed the efficacy of the Erbium Yag laser using the ICIQ-UI0-SF at 6 months’ follow-up [30, 32,33,34,35,36]. All demonstrated an improvement or cure of symptoms, with significant reduction on ICIQ-UI-SF scores. The number of patients in these studies were small, ranging from 22 to 45. One study, by Ogrinc et al., demonstrated a significant improvement in ICIQ-SF-UI scores in 108 of 175 women 12 months following therapy [36]. Gaspar et al. and Tien et al. showed improved pad weights in women with SUI 6 months following therapy [32, 39]. None of the studies reported serious adverse events.

A recent paper reported the use of PRISMA guidelines to design the systematic review [40]. Thirteen studies were included that recruited 818 patients who underwent laser therapy for SUI. Most studies had a follow-up period of up to 6 months, although one study had a 36-month follow-up. ICIQ-UI SF, Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptom (FLUTS) score, UDI-6, KHQ, VAS, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire 12 (PISQ-12), Incontinence Severity Index (ISI) were used. The authors concluded that laser therapy may be a useful, minimally invasive approach for treating SUI. However, our analysis does not allow firm conclusions or recommendations.

Conclusions

When recommending a therapy to a patient, it is important to remember the levels of scientific evidence. Recognizing that most LBD literature pertaining to GSM, SUI, and VL is observational, there is an urgent need for large, long-term, randomized, and placebo- and drug-controlled studies to further evaluate the safety and efficacy of this procedure. While the same technology may have been used in plastic surgery on skin and facial tissues, the potential for long-term complications when used on vulvovaginal tissues needs to be further studied and elucidated, perhaps in a registry form. The FDA has established the Women’s Health Technologies Strategically Coordinated Registry Network (CRN) to provide more complete evidence in clinical areas unique to women, such as pelvic floor disorders [41]. In some countries, EBDs are associated with high cost to the patients, and providers should not use it for indications not supported by scientific evidence. There is no literature available reporting outcomes after EBD based on physician specialty or level of training. As such, the committee cannot make recommendations about provider training or expertise needed to perform laser-based procedures for a given indication. In the United States, medicolegally, any physician with a medical license or their nurse practitioners can potentially perform these laser-based procedures. Although the review of the literature shows it may be used to treat GSM, there appears to be insufficient evidence of its long-term efficacy and side effects. Evidence from robustly conducted RCTs with long-term follow-up comparing laser with placebo or hormonal treatment are lacking. Similarly, well-designed case–control studies are required to further investigate potential benefits, harm, and efficacy of laser therapy for treating GSM, VL, and SUI symptoms. The therapeutic advantages of nonsurgical laser-based devices in urogynecology can only be recommended after robust clinical trials have demonstrated their long-term complication profile, safety, and efficacy.

References

Salvatore S, et al. Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue: an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22(8):845–9.

FDA. FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA Safety Communication. 2018. [2018 August 1].

Practice, C.o.G. ACOG Committee opinion no. 378: vaginal rejuvenation and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):737.

American-College-of-Plastic-Surgeons. Nonsurgical vaginal rejuvenation. 2018. [29 October 2018]. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/cosmetic-procedures/nonsurgical-vaginal-rejuvenation.

Nappi RE, et al. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in four European countries: evidence from the European REVIVE survey. Climecteric. 2016;19:188–97.

Portman DJ, ML G. Vulvovaginal atrophy terminology consensus conference panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's sexual health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063–8.

Pardo JS, Solà VD, Ricci PA. Colpoperineoplasty in women with a sensation of a wide vagina. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1125–7.

Moore RD, Miklos JR, O C. Evaluation of sexual function outcomes in women undergoing vaginal rejuvenation/vaginoplasty procedures for symptoms of vaginal laxity/decreased vaginal sensation utilizing validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ-12). Surg Technol Int. 2014;24:253–60.

Haylen BT, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35(2):137–68.

Pauls RN, Fellner AN, GW D. Vaginal laxity: a poorly understood quality of life problem; a survey of physician members of the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA). Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1435–48.

Millheiser L, Kingsberg S, Pauls R. A cross-sectional survey to assess the prevalence and symptoms associated with laxity of the vaginal introitus [abstract 206]. In: ICS Annual Meeting. Toronto, Ontario, Canada; 2010.

Roos AM, Sultan AH, R T. Sexual problems in the gynecology clinic: are we making a mountain out of a molehill? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:145–52.

MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. BJOG. 2000;107:1460–70.

Karcher C, N S. Vaginal rejuvenation using energy-based devices. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2:85–8.

Tadir Y, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:137–59.

Lang P, Karram M. Lasers for pelvic floor dysfunctions: is there evidence? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29(5):354–8.

Arunkalaivanan A, Kaur H, Onuma O. Laser therapy as a treatment modality for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a critical appraisal of evidence. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:681–5.

Isaza PG, Jaguszewska K, Cardona JL, Lukaszuk M. Long-term effect of thermoablative fractional CO2 laser treatment as a novel approach to urinary incontinence management in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(2):211–5.

Lapii GA, Yakovleva AY, Neimark AI. Structural reorganization of the vaginal mucosa in stress urinary incontinence under conditions of Er:YAG laser treatment. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2017;162(4):510–4.

Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Dover JS, Arndt KA. The spectrum of laser skin resurfacing: nonablative, fractional, and ablative laser resurfacing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):719–37.

Pitsouni E, et al. Microablative fractional CO2-laser therapy and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: an observational study. Maturitas. 2016;94:131–6.

Siliquini GP, et al. Fractional CO2 laser therapy: a new challenge for vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2017;20(4):379–84.

Sokol ER, Karram MM. An assessment of the safety and efficacy of a fractional CO2 laser system for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2016;23(10):1102–7.

Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–4.

Gaspar A, et al. Efficacy of erbium:YAG laser treatment compared to topical estriol treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):160–8.

Behnia-Willison F, et al. Safety and long-term efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;213:39–44.

Pieralli A, et al. Erratum to: Long-term reliability of fractioned CO2 laser as a treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) symptoms. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296(6):1237.

Cruz VL, Steiner ML, Pompei LM, Strufaldi R, Fonseca FLA, Santiago LHS, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25(1):21–8.

Gambacciani M, et al. Rationale and design for the vaginal erbium laser academy study (VELAS): an international multicenter observational study on genitourinary syndrome of menopause and stress urinary incontinence. Climacteric. 2015;18(Suppl 1):43–8.

Gambacciani M, Levancini M, Cervigni M. Vaginal erbium laser: the second-generation thermotherapy for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric. 2015;18(5):757–63.

Cardozo L. Fractional microablative CO2-laser versus photothermal non-ablative erbium:YAG-laser for the management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a non-inferiority, single-blind randomised controlled trial https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03288883?cond=gsm&rank=32018. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03288883?cond=gsm&rank=3. Accessed 26 Nov 2018.

Gaspar A, Brandi H. Non-ablative erbium YAG laser for the treatment of type III stress urinary incontinence (intrinsic sphincter deficiency). Lasers Med Sci. 2017;32(3):685–91.

Fistonic N, et al. Minimally invasive, non-ablative Er:YAG laser treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women--a pilot study. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31(4):635–43.

Pardo JI, Sola VR, Morales AA. Treatment of female stress urinary incontinence with erbium-YAG laser in non-ablative mode. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;204:1–4.

Fistonić N, et al. First assessment of short-term efficacy of Er: YAG laser treatment on stress urinary incontinence in women: prospective cohort study. Climacteric. 2015;18(sup1):37–42.

Ogrinc UB, Sencar S, Lenasi H. Novel minimally invasive laser treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47(9):689–97.

Fistonic I, et al. Laser treatment of early stages of stress urinary incontinence significantly improves sexual life. In: Annual Conference of European Society for Sexual Medicine. 2012.

Khalafalla M, et al. Minimal invasive laser treatment for female stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2015;2(2):00035.

Tien YW, et al. Effects of laser procedure for female urodynamic stress incontinence on pad weight, urodynamics, and sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(3):469–76.

Pergialiotis V, et al. A systematic review on vaginal laser therapy for treating stress urinary incontinence: do we have enough evidence? Int Urogynecol J. 2017.

FDA. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on efforts to safeguard women’s health from deceptive health claims and significant risks related to devices marketed for use in medical procedures for vaginal rejuvenation. 2018. (cited 2018 August 1).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Veronica Mallet (2017 committee member) and Dr. Pallavi Latthe (2018-2019 committee chair) for their invaluable contributions to this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shobeiri, S.A., Kerkhof, M.H., Minassian, V.A. et al. IUGA committee opinion: laser-based vaginal devices for treatment of stress urinary incontinence, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and vaginal laxity. Int Urogynecol J 30, 371–376 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3830-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3830-0