Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The object of this review was to assess the efficacy and safety of urethral bulking agents (UBA), principally Macroplastique and Bulkamid, in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence (SUI).

Methods

MEDLINE® and EMBASE® databases were systematically searched up to June 2016. Year of publication, study type, outcome measures, urodynamics before and after the procedure, number of participants, procedure complications, proportion requiring repeat injections or surgical procedures, frequency of follow-up, and results were analysed.

Results

The use of Bulkamid and Macroplastique for the treatment of female SUI was described in 26 studies. Studies used modalities including the visual analogue scale, Likert scale, International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ), Patient Global Improvement Questionnaire (PGIQ) and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and showed success rates ranging from 66% to 89.7% at 12 months follow-up. Objective improvements in patient symptoms were measured using urodynamics, 24-h pad tests, cough tests and voiding diaries. Studies showed variable objective success rates ranging from 25.4% to 73.3%. Objective findings for UBAs remain less well documented than those for the midurethral sling procedure.

Conclusions

There are a range of complications associated with UBAs, the most common being urinary tract infection. However, it remains a very well tolerated procedure in the majority of patients. UBAs should be considered as an alternative in patients unsuitable for more invasive procedures and those willing to accept the need for repeat injections. The majority of the literature focuses on subjective improvement measures rather than objective improvement measures. Further randomized controlled trials directly comparing UBAs are required to indicate the most effective agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a common socially debilitating condition predominantly affecting women with a prevalence of between 10% and 40% [1]. Managing and treating SUI comes at a significant cost to the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), estimated at approximately £353.6 million per annum [2]. Normal urinary continence relies on the functional coordination of the anatomy by the nervous system. The pelvic floor creates the support required by the bladder and urethra to sustain transmission of abdominal pressure to the proximal urethra, ultimately resulting in continence [3]. It has been hypothesized that reductions in the urethral closure pressure superimposed on the transmission of pressure from the abdomen to the urethra results in SUI [4]. Furthermore, recent findings have highlighted the role of midurethral support in the maintenance of continence [5]. Risk factors include advancing age, higher parity, vaginal delivery, obesity and postmenopausal status [6].

The current gold standard treatment of SUI is placement of a midurethral sling via either the retropubic or the transobturator route. These procedures aim to provide support at the midurethral level with the sling acting as a hammock preventing the urethra from dropping. Typically, a synthetic mesh is positioned posterior to the proximal urethra lifting the urethra up into a position where it can withstand increases in intraabdominal pressure so that continence is maintained [3]. The use of midurethral tapes has come under scrutiny recently in relation to mesh complications including infection, chronic pain and erosion. Midurethral tapes have been withdrawn from use in the NHS in Scotland pending further investigation, but not in the rest of the UK. These concerns have led to the focus being shifted to existing urethral bulking agents (UBAs) and their development for use in the treatment of SUI

The American Urology Association has recommended the use of UBA in elderly patients, patients with an increased risk of anaesthetic complications, and patients reluctant to undergo a more invasive procedure [7]. In addition, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [8] advises that UBAs be considered in patients with significantly decreased urethral mobility and patients who have a history of failed conservative treatment [8]. In 2011 glutaraldehyde-treated bovine collagen (Contigen) was withdrawn worldwide due to its tendency to be absorbed leading to recurrence of symptoms. This resulted in the need for new agents, most notably polydimethylsiloxane (Macroplastique) and polyacrylamide hydrogel (Bulkamid) [9, 10]. UBAs provide additional support when injected into the mid-urethra. Once implanted into the urethral submucosa they provide a cushion helping to increase urethral sphincter pressure thus improving continence [11].

This aim of this systematic review was to assess the efficacy and safety of UBAs alone, principally Macroplastique and Bulkamid. We compared the two UBAs to determine whether either is superior in the treatment of women with SUI.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis (PRISMA) statement (http://www.prisma-statement.org).

Study eligibility criteria

Studies outlining the use, efficacy and safety of UBAs in the treatment of female SUI as an alternative to more invasive traditional surgical procedures were included. Review articles, conference abstracts, letters, animal studies and studies involving the use of models were excluded.

Information sources and search

Using the NICE Healthcare Databases Advanced Search (https://www.evidence.nhs.uk) a broad search of the English literature was conducted in June 2016 via the MEDLINE (2006 to June 2016) and EMBASE (2006 to June 2016) databases. The keywords used included: ‘bulking agent’, ‘bulkamid’, ‘macroplastique’ and ‘urinary stress incontinence’. In addition to studies obtained via the databases, further studies were acquired from the references cited in recent review articles.

Study selection and data collection

One reviewer (Z.S.) independently screened the abstracts of the studies identified in the database search to identify those that were potentially relevant. The full text of each potentially relevant paper was then independently reviewed by two authors (Z.S. and H.A.) to determine whether the paper included certain topics of interest such as bulking agents, human studies, SUI, and follow-up on safety and efficacy. Conflicts between reviewers were discussed until there was 100% agreement on the studies finally to be included.

Data extraction and analysis

From each study certain information was extracted and entered into a table for summary and analysis. Information extracted included: year of publication, type of study, outcome measures, urodynamics before and after the procedure, number of study participants, procedure complications, proportion of subjects requiring repeat injections or surgical procedures, frequency of follow-up, and results.

Results

Study selection

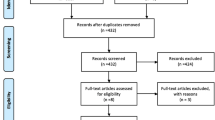

A total of 223 potentially relevant publications were identified from the literature search, but, following abstract review this was brought down to 53. Full text analysis led to the exclusion of a further 27 studies due to duplication, lack of relevance or lack of full text journal publication. Thus, a final count of 26 studies were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Bulkamid

An overview of the studies identified in which Bulkamid was used for the treatment of female SUI is presented in Table 1. The review showed that Bulkamid treatment improves patient quality of life (QoL) as shown in terms of subjective success measured using various methods including the visual analogue scale, Likert scale, International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ), Patient Global Improvement Questionnaire (PGIQ and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ). One study showed a high subjective success rate of 74.4% [18]. In another study with 25 subjects Bulkamid improved subjective symptoms in all patients except two who felt that the treatment had affected their social life [16]. In other studies subjective cure rates varied over time: at 1, 6, and 12 months the rates were 87%, 71%, and 66% respectively [22]. Finally, one study highlighted the variability in QoL following treatment with Bulkamid: QoL was found to be considerably improved in 40% of patients, slightly improved in 21%, unchanged in 29% and worsened in 10% [21]. Considering sexual function specifically, one study demonstrated an improvement following treatment with Bulkamid. In this study, 23 of 29 women treated continued to be sexually active and the subjective success rate was 89.7% at 12 months [20].

In the Bulkamid studies, objective success was measured using urodynamics, the 24-h pad test, the cough test and the number of incontinence episodes. In one study, full continence as defined by a negative cough test was achieved in 14 of 46 patients (30.4%) following treatment [12]. The same study showed a significant reduction in urine leakage, ranging from −61.5 ml to −197.5 ml as demonstrated by the pad test, but showed no significant changes in urodynamic parameters except for a reduction in voided volume [12]. Another study investigated the use of Bulkamid in 60 women who had previously had a failed midurethral sling procedure. In that study, 56.7% of the women had a negative cough test and <2 g urine in a 1-h pad test at 1 month, and the negative cough test rates decreased to 43.3% and 25.4% at 6 and 12 months, respectively [13]. In another study including 135 patients, the 24-h pad test showed a significant reduction from a median of 29 g at baseline to 4 g at 12 months, and the number of incontinence episodes per 24 h decreased significantly in the group as a whole from a median of 3.0 (range 0.0–14.7) at baseline to 0.7 (range 0.0–16.0) at 12 months [22].

Macroplastique

An overview of the studies identified in which Macroplastique was used for the treatment of female SUI is presented in Table 2. These studies used similar methods for the measurement of subjective success, including the visual analogue scale and the questionnaires Incontinence Quality of Life Scale (I-QOL), Incontinence Impact Questionnaire-7 (IIQ-7) and Urogenital Distress Inventory-6 (UDI-6). In one study, the patients reported median I-QOL, IIQ-7, and UDI-6 scores of 57.27, 80.95 and 72.22, respectively, before treatment and 85.45, 23.81 and 22.22, respectively, after treatment, suggesting improved subjective success rates [24]. In another study, mean symptom VAS scores decreased significantly from 8.5 ± 1.4 before treatment to 1.8 ± 1.5 after treatment. In another study, mean I-QOL scores after Macroplastique treatment improved from 49.5 to 70.9 for avoidance and limiting behaviour, from 47.7 to 69.4 for psychological impact, and from 41.9 to 64.2 for social embarrassment [25]. In the final study, on the Patient Global Impression of Improvement scale 85% of 66 patients considered themselves dry or markedly improved, 8% slightly improved and a further 8% unchanged [26].

In the Macroplastique studies, objective success was measured using urodynamics, the 24-h pad test, the cough test, and voiding diaries to elicit the number of incontinence episodes. Ghoniem et al. [26] found that, along with subjective success, Macroplastique reduced urine loss by >50% in 53 of 63 (79%) patients according to the 1-h pad test. In another study, the objective cure rate decreased from 55% at 6 months to 44% at 12 months. Voiding diaries showed that the number of incontinence episodes over 3 days decreased from 15.2 ± 6.6 to 7.9 ± 7.7 after treatment. However, the same study did not show any significant changes in urodynamic parameters after treatment (peak flow 18.8 ± 3 ml/s vs. 19 ± 2 ml/s, flow time 21.6 ± 2.9 s vs. 19.3 s, postvoid residual volume 21.8 ± 10.1 ml vs. 20.8 ± 6.7 ml). However, maximum urethral closure pressure improved significantly from 22.2 ± 10.1 cm H2O to 30 ± 10.2 cm H2O, indicating restored continence [27]. In the study by Plotti et al. [30], 10 of 24 patients were cured of SUI and were negative on the cough test. In addition, there was a significant reduction in the number of incontinence episodes over 3 days after treatment (14.5 ± 5.8 to 4.3 ± 7.9). However, maximum urethral closure pressure improved significantly from 26.4 ± 23.5 cm H2O to 36.3 ± 24.4 cm H2O after treatment, indicating restored continence. Finally, in the study by Tamanini et al. [31], patients showed objective improvement in terms of pad usage which decreased significantly from 3.5 per day to 0.9 per day, and 1-h pad weight which decreased significantly from 53.8 to 5.9 g. Valsalva leak point pressure also improved, indicating a 73.3% rate of cure/improvement.

Safety of Bulkamid and Macroplastique

We also evaluated the side effect profile of both UBAs. The most common adverse effect was urinary tract infection for both Bulkamid and Macroplastique (11% and 9%, respectively). Bulkamid caused more of each of the most commonly occurring adverse effects than Macroplastique, except for acute urinary retention (3% vs. 9%) and dysuria (1% vs 7%). It is difficult to compare the two agents with confidence given the difference in the total numbers of patients treated with Bulkamid (n = 777) and with Macroplastique (n = 351). The most common adverse effects associated with the two bulking agents are listed in Table 3.

Discussion

Bulkamid and Macroplastique were designed to provide a less invasive treatment for SUI in women. However, their use has been scrutinized and questions have been asked about their effectiveness and safety. Our findings showed that UBAs can relieve the symptoms in patients with SUI. However, the degree of symptom relief depends on whether subjective or objective measurements are used. Subjective success was often achieved much sooner than objective success. For example, in two of the studies, immediately after the procedure [17] and at 1 month [22] subjective success rates were 75% and 87%, respectively. This might be explained by the outcome measures used in the studies. The first used physical examination immediately after the procedure which does not take into account the patient’s own view of success and instead focuses on that of the examiner. Furthermore, the time at which outcome is measured may not be long enough for the true success rate to become apparent. As shown previously, the success rate, whether subjective or objective, deteriorates over time. The second study used questionnaires including ICIQ and QoL and VAS. It is important to remember that patients experiencing any improvement in symptoms will score lower on the questionnaires. However, subjective responses may be prone to error; for example, if two patients show the same reduction in the amount of urine leaked after the procedure, the patient leaking more urine before the procedure may report a lower degree of success using the questionnaire. When comparing interventions, subjective and objective methods can give different results. However, achieving the best possible outcome for the patient is only possible if treatment goals are discussed and subjective perceptions identified.

Much variability was also noted in the results at about 12 months after the procedure. In addition to the outcome method used, as described above, there are a number of factors which may have been responsible for this. Firstly, patient demographics play an important role. One study [25] showed a subjective cure rate of 34% at a median follow-up of 10 months, but another study [26] showed a rate of 57%. This discrepancy might be explained by the fact that all of the patients included in the first of these studies [25] had previously had a failed midurethral sling procedure for SUI, which may indicate increased complexity of their condition. Secondly, given that the efficacy of UBA treatment does reduce over time, it is not unreasonable to imagine that individuals will require repeat therapy sooner or later than others. This may also be one of the factors accounting for the variability in success rate found at about 12 months.

Strengths and limitations

There are certain limitations in the quality of the evidence provided by the studies identified. With regard to the hierarchy of evidence, there were only three randomized controlled trials found, none of which directly compared Bulkamid and Macroplastique. Instead these randomized controlled trials used Contigen as the control, a UBA that is no longer available. Although we tried to compare outcomes at 12 months based on case series, raw data were not reported in all studies making comparisons difficult. As such, it is still unclear whether either bulking agent is superior to the other as a treatment for SUI. In addition, the aim of this systematic review was not to compare UBA with the current gold standard therapy for SUI, midurethral tape procedures. Finally, with regard to methodological variability, many of the studies reviewed reported subjective measures of success, whereas fewer reported objective findings, with fewer still reporting both.

Implications for future research

We believe that given the recent rise in interest in UBAs as a less invasive option for improving QoL and providing symptomatic relief in patients with SUI, future studies should directly compare the efficacy of popular UBAs on the market. Furthermore, study methodology should be changed to reflect the need to provide more objective measures of success. It would also be useful to divide patients into cohorts reflecting the severity of their condition, to help better gauge which patient group stands to gain the most from UBA therapy. Lastly, given the decline in efficacy of UBAs over time, follow-up periods should be longer to allow more accurate investigation of this issue.

Conclusion

SUI is a common debilitating condition in women. Current standard treatment involves the surgical option of midurethral sling procedures. For those who cannot undergo such an invasive procedure or for those who want to avoid a synthetic mesh procedure and for whom there is acceptance that repeat treatments may be required, interest in the use of UBA has started to increase. Two of the more popular agents, Bulkamid and Macroplastique, have shown significant promise with studies showing statistically significant improvements in subjective QoL. However, improvements in objective measurements are not as well documented in the literature. We have shown that their safety profiles are similar, with urinary tract infection being the most common adverse effect. This study further highlights the advantages and disadvantages of UBAs, but further randomized controlled trials directly comparing UBAs are required to indicate the most effective agent.

References

Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Diokno A, Herzog AR, Hjälmås K, Lapitan MC. Epidemiology and natural history of urinary incontinence in women. Urology. 2003;62(4 Suppl 1):16–23.

Turner DA, Shaw C, McGrother CW, Dallosso HM, Cooper NJ, Team MI. The cost of clinically significant urinary storage symptoms for community dwelling adults in the UK. BJU Int. 2004;93(9):1246–1252.

Ford AA, Rogerson L, Cody JD, Ogah J. Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD006375.

Enhorning G. Simultaneous recording of intravesical and intra-urethral pressure. A study on urethral closure in normal and stress incontinent women. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1961;Suppl 276:1–68.

Petros PE, Ulmsten UI. An integral theory and its method for the diagnosis and management of female urinary incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1993;153:1–93.

Wilson PD, Herbison RM, Herbison GP. Obstetric practice and the prevalence of urinary incontinence three months after delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103(2):154–161.

American Urological Association. Incontinence 2016. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association; 2017. https://www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/incontinence.cfm. Accessed 30 Jan 2017.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intramural urethral bulking procedures for stress urinary incontinence in women. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2005. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/IPG138/chapter/2-The-procedure. Accessed 30 Jan 2017.

Ghoniem GM, Miller CJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Macroplastique for treating female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(1):27–36.

Kasi AD, Pergialiotis V, Perrea DN, Khunda A, Doumouchtsis SK. Polyacrylamide hydrogel (Bulkamid®) for stress urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(3):367–375.

Klarskov N, Lose G. Urethral injection therapy: what is the mechanism of action? Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27(8):789–792.

Krhut J, Martan A, Jurakova M, Nemec D, Masata J, Zvara P. Treatment of stress urinary incontinence using polyacrylamide hydrogel in women after radiotherapy: 1-year follow-up. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(2):301–305.

Zivanovic I, Rautenberg O, Lobodasch K, von Bünau G, Walser C, Viereck V. Urethral bulking for recurrent stress urinary incontinence after midurethral sling failure. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016. doi:10.1002/nau.23007

Sokol ER, Karram MM, Dmochowski R. Efficacy and safety of polyacrylamide hydrogel for the treatment of female stress incontinence: a randomized, prospective, multicenter north american study. J. Urol. 2014;192(3):843–849.

Martan A, Masata J, Svabík K, Krhut J. Transurethral injection of polyacrylamide hydrogel (Bulkamid®) for the treatment of female stress or mixed urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;178:199–202.

Mouritsen L, Lose G, Møller-Bek K. Long-term follow-up after urethral injection with polyacrylamide hydrogel for female stress incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(2):209–212.

Krause HG, Lussy JP, Goh JT. Use of periurethral injections of polyacrylamide hydrogel for treating post-vesicovaginal fistula closure urinary stress incontinence. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(2):521–525.

Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Alessandri F, Medica M, Gabelli M, Venturini PL, Ferrero S. Outpatient periurethral injections of polyacrylamide hydrogel for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: effectiveness and safety. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;288(1):131–137.

Mohr S, Siegenthaler M, Mueller MD, Kuhn A. Bulking agents: an analysis of 500 cases and review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24(2):241–247.

Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Alessandri F, Medica M, Gabelli M, Venturini PL, Ferrero S. Periurethral injection of polyacrylamide hydrogel for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: the impact on female sexual function. J Sex Med. 2012;9(12):3255–3263.

Trutnovsky G, Tamussino K, Greimel E, Bjelic-Radisic V. Quality of life after periurethral injection with polyacrylamide hydrogel for stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(3):353–356.

Lose G, Sørensen HC, Axelsen SM, Falconer C, Lobodasch K, Safwat T. An open multicenter study of polyacrylamide hydrogel (Bulkamid®) for female stress and mixed urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(12):1471–1477.

Lose G, Mouritsen L, Neilsen JB. A new bulking agent (polyacrylamide hydrogel) for treating stress urinary incontinence in women. BJU Int 104 100;98(1).

Gumus II, Kaygusuz I, DerbentA, Simavli S, Kafali H. Effect of the Macroplastique Implantation System for stress urinary incontinence in women with or without a history of an anti-incontinence operation. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(6):743–749

Lee HN, Lee YS, Han JY, Jeong JY, Choo MS, Lee KS. Transurethral injection of bulking agent for treatment of failed mid-urethral sling procedures. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(12):1479–1483.

Ghoniem G, Corcos J, Comiter C, Westney OL, Herschorn S. Durability of urethral bulking agent injection for female stress urinary incontinence: 2-year multicenter study results. J Urol. 2010;183(4):1444–1449.

Zullo MA, Ruggiero A, Montera R, Plotti F, Muzii L, Angioli R, et al. An ultra-miniinvasive treatment for stress urinary incontinence in complicated older patients. Maturitas. 2010;65(3):292–295.

ter Meulen PH, Berghmans LCM, Nieman FHM, van Kerrebroeck PEVA. Effects of Macroplastique® Implantation System for stress urinary incontinence and urethral hypermobility in women. Int Urogynecol J 2009;20(2):177–183.

Ghoniem G, Corcos J, Comiter C, Bernhard P, Westney OL, Herschorn S. Cross-Linked Polydimethylsiloxane Injection for Female Stress Urinary Incontinence: Results of a Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled, Single-Blind Study. J Urol 2009;181(1):204–210.

Plotti F, Zullo MA, Sansone M, Calcagno M, Bellati F, Angioli R, et al. Post radical hysterectomy urinary incontinence: a prospective study of transurethral bulking agents injection. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(1):90–94.

Tamanini JT, D’Ancona CA, Netto NR. Macroplastique implantation system for female stress urinary incontinence: long-term follow-up. J Endourol. 2006;20(12):1082–1086.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Financial disclaimer

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siddiqui, Z.A., Abboudi, H., Crawford, R. et al. Intraurethral bulking agents for the management of female stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 28, 1275–1284 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3278-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3278-7