Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Pelvic anatomy is complex and intimate knowledge of variabilities in anatomical relationships is critical for surgeons to safely perform surgical procedures. Three-dimensional Imaging provides the opportunity to analyze undisturbed anatomical relationships. The authors hypothesized that three-dimensional models created from pelvic computed tomography angiograms could be used to obtain vascular anatomical measurements, and that the measurements obtained from three-dimensional models would be similar to those from cadaver studies.

Methods

We included all pelvic computed tomography angiograms that were acquired in female patients older than 18 years at our institution within the previous 5 years. Three-dimensional models were created using the Invivo5 software based on the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine files. Structures of interest were virtually dissected and measured replicating previous cadaver studies. Statistical analysis of demographics and measurements was performed.

Results

The final analysis included 87 studies. The average age of the subjects was 66.9 years and their average BMI was 26.1 kg/m2. Of the 87 subjects, 12.6% had a history of hysterectomy, 2.3% a history of a continence procedure, and 1.1% a history of a prolapse procedure. The range of distance between the ischial spine and the pudendal artery was 3–17 mm. The closest vessels to the lower edge of the symphysis pubis were the obturator vessels. The aberrant corona mortis vessel was present in 27.9% of the subjects. Prior hysterectomy was associated with changes in the measurements of the obturator arteries with minimal changes in other measurements.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that this technology provides similar measurements to those found in previous unembalmed cadaver studies. This technology offers a great opportunity to study anatomical relationships in a native undisturbed state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anatomical knowledge has been a cornerstone for the development of the different surgical disciplines. Traditional methods to study surgical approaches include cadaveric dissection and two-dimensional imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). Cadaveric dissections can be limited by the alterations in anatomical relationships caused by fixation and the dissection itself. Traditional imaging studies offer the opportunity to analyze anatomy without disturbing proximal anatomical structures but lack the three-dimensional perspective of cadaver studies [1].

Recently three-dimensional reconstruction of CT and MRI images has become available. This technology allows unprecedented views of anatomical relationships in a three-dimensional array without disturbing related structures [2–5]. The anatomy of the pelvis is quite complex and highly variable. In addition, because the soft tissues are encompassed by the bony confines of the pelvic bones, conventional dissection techniques often significantly alter anatomical relationships. Thus, comprehensive studies of the relationships among important pelvic support structures are wanting. This novel technology gives investigators the opportunity to study important pelvic structures in their native undisturbed state. A PubMed search using the MeSH terms “vascular”, “three-dimensional”, “retropubic space”, “pudendal artery”, “sacrospinous” and “obturator arteries” on 29 September 2016 did not find any publish studies using three-dimensional imaging techniques investigating vascular structures of the retropubic space and around the ischial spine in the human pelvis.

Our primary objective was to map the important vascular structures and their relationships to surrounding structures in the retropubic space and ischial spine using three-dimensional models reconstructed from CT scans. The secondary objective was to compare our findings with the most representative previously published measurements of the same landmarks obtained from cadaver studies.

Materials and methods

Patient population

The University of Massachusetts institutional review board approved this study. We retrieved the images of all adult women older than 18 years who had undergone pelvic CT angiography (PCTA) using a 64 multidetector-row scanner within the past 5 years at our institution. Patients with a history of malignancy, pelvic fracture, pelvic or abdominal radiotherapy and lymph node dissection were excluded from the study. Subject demographics were obtained from medical records and included age, body mass index (BMI) and history of hysterectomy, prolapse, and/or continence procedures.

Image acquisition

The clinical condition of the patients was determined using a standardized protocol and then images were obtained with a Philips Brilliance 40 CT scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) from the lower pole of the kidney to the mid-femur or toes when applicable. Intravenous contrast medium was monophasically infused at a rate of 5 mL/s.

Image reconstruction and interpretation

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) files from deidentified individual studies were transferred to a workstation loaded with the Invivo5 software (Anatomage Inc, San Jose, CA). Three-dimensional models were created using the DICOM files using the volume render component of the software. A single reader (O.D.-G.) who was trained to use the software performed all the image reconstructions and readings. All measurements were obtained in millimeters.

Anatomical region measurements

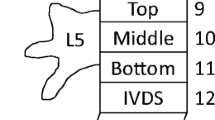

Anatomical regions of interest were virtually dissected using the Invivo5 software. Densities were modified to properly identify vascular and bony structures and differentiate them from other soft-tissue elements. For the measurements of the pudendal artery, the vessel was traced and isolated (Fig. 1). The final model was rotated and the closest distance between the pudendal artery and the ischial spine was measured replicating previous cadaver studies (Fig. 2) [6].

For study of the retropubic space anatomy, the pelvic viscera and other structures that obscured visualization of the vasculature were virtually dissected. Measurements of the structures related to retropubic procedures were obtained including the height of the symphysis pubis, and the distances from the midline and the inferior border of the pubic rami to the obturator artery, to the corona mortis (when present), to the external iliac vein and artery, and to the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 3) [7, 8].

Analyses were performed using Stata/MP 14.1 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software, release 14; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Subject demographics and anatomical measurements were analyzed in terms of frequency and percent, or mean, standard deviation and range. Wilcoxon’s rank sum test was used to compare patients who had a history of hysterectomy and subjects who did not.

Results

Of 215 PCTA studies identified that had been performed at our institution during the study time period, 87 were included in the final analysis. PCTA studies in male patients were eliminated (94 studies). Eleven patients had one or more of the exclusion criteria and 23 patients had more than one PCTA study. For these subjects, only the more recent study was analyzed. The subjects’ mean (±SD) age was 66.9 ± 14.4 years and their mean BMI was 26.1 ± 6.3 kg/m2. The majority were Caucasian (91.5%), 5.74% were Hispanic, and 2.75% identified as other race. Ten subjects (11.4%) had a prior hysterectomy, 17.2% a prior laparoscopy, 2.3% a prior incontinence procedure, and 1.1% prior prolapse repair. In 20 subjects (23%) no documented gynecologic history was documented and we were unable to corroborate the type of hysterectomy. Fifty-three subjects (61%) had hypertension and 14 (16%) had diabetes.

The most common primary indication for PCTA was aortic abdominal aneurysm in 46 studies. Other indications included abdominal pain (16), claudication (6), renal stenosis (5), aortoiliac disease (5) and other (9). Other indications for PCTA included fibromuscular dysplasia of the aortic vessels, monitoring embolization of splenic aneurysms, aortoiliac bypass monitoring, connective tissue disease vessel evaluation, foot pain and dyspnea.

The principal findings for the measurements of the vascular anatomy of the pudendal artery are shown in Table 1. The shortest distance from the ischial spine prominence to the pudendal artery was 2.7 mm and the longest was 17 mm.The vascular retropubic space anatomy findings are shown in Table 2. The overall prevalence of the aberrant corona mortis vessel was 27.9%. The obturator artery vessels were the closest arterial vascular element to the midline and lower edge of the symphysis pubis.

Anatomical variations in the vascular anatomy caused by hysterectomy were explored, and the findings are shown in Table 3. Most of the measurements showed no significant differences except for both obturator arteries (p = 0.043 for the right, p = 0.036 for the left).

Discussion

Most of the information available regarding the vascular surgical anatomy of the ischial spine and retropubic space is from small series of embalmed and unembalmed cadaver studies. Cadaver studies are limited by the sparse demographics and absent clinical information about the donor, as well the cost and difficulty of gathering large numbers of specimens. In addition, preparation of the specimen and dissection itself often disturb the natural anatomical relationships, potentially limiting the external validity [10].

We used PCTA because it provides a high resolution (small slice thickness), combined with arterial contrast which allows easy recognition of the vessels of interest. Conventional MRI with 1.5 T magnets is inferior to PCTA in terms of spatial resolution, slice thickness and resolution of noncalcified structures [11]. Because of the quality of images that we had available we consider that PCTA provided better resolution for the purposes of our study. MRI with 3 T magnets can provide thinner slices and better resolution than MRI with 1.5 T magnets, but unfortunately, this technology is expensive and not widespread. MRI with 3 T magnets can provide images with a quality superior to PCTA and with the added benefit of using non-ionizing radiation. It is possible that in the future this technology could be incorporated into clinical practice to provide a map of the pelvic anatomy prior to a surgical procedure enabling individualization of care.

Most of the subjects in this study had no prior prolapse or continence procedures, but a reasonable number of them had a hysterectomy (12%). Our analysis showed that a hysterectomy caused minimal changes in the anatomy of the regions of interest in this study. Our study was not powered or designed to look specifically for this situation, and similar cadaver studies, also due to the limited number of donors, have failed to show a significant difference. We believe that this technology will help in the future to clarify the role of pelvic surgery and changes in the pelvic anatomy. Our value of the distance from the pudendal artery to the ischial spine is similar to those reported from cadaver studies, although we found this structure slightly closer than previously reported. Where cadaveric data were available, our measures were similar to the cadaveric values [6–8]. These studies resulted in the recommendation to place suspension suture needles at least 2 cm medial to the spine to avoid potential neurovascular damage. Our findings support this recommendation [6, 12, 13].

Concerning the retropubic space anatomy, our findings are consistent in showing that the obturator artery vessels are the closest arterial vascular element to the midline, as found in cadaver studies [7]. The inferior epigastric vessels and the external iliac artery and vein appear to be quite far away from the midline, but there are case reports of damage to these vessels by a sling trocar [14]. Surgeons should be aware that subtle changes in the angle of introduction of a transvaginal trocar can lead to significant deviation of the tip of the trocar. This deviation can result in injury to these vessels. Another vascular element in the retropubic space to considerer is the aberrant corona mortis vessel. Most of its anatomical descriptions come from mixed populations (males and females) and to our knowledge there is only one cadaver study in females looking exclusively for the presence of this vessel [9]. This was present in over 25% of our subjects This vessel has been associated with some retropubic space bleeding episodes after retropubic and transobturator sling placement and injury to the vessel could result in significant retropubic bleeding [15, 16]. We did not identify previous articles exploring the effect of hysterectomy on vascular pelvic anatomy. We do not have a plausible explanation as to why the distance from obturator arteries to the lower edge of the symphysis pubis was the only variation that reached statistical significance. Further studies exploring this finding are required.

The main strength of our study is that it is the largest study of the retropubic space and vascular anatomy around the ischial spine. Most of our findings represent large vessels that can be visualized by PCTA without three-dimensional reconstruction. Our study was limited by the inability of the imaging to show nerves and other structures that are of surgical interest. Smaller clinically relevant veins could not be visualized and previous studies have suggested some aberrant anastomoses, specifically with the corona mortis [17]. All patients had major vessel pathology that raises the possibility that their vascular anatomy may have been different from that in a population without these medical conditions, but this seems unlikely.

Conclusions

We consider that measurements obtained from three-dimensional imaging models reconstructed from PCTA scans are consistent with those obtained in unembalmed cadaver studies. The aberrant corona mortis vessel was present in a relatively large proportion of our subjects and appears to be closer to the midline than previously described. Prior hysterectomy appears to have a minimal impact in the vascular anatomy of these regions, but further studies are required to corroborate this finding. This technology offers a great opportunity to study anatomical relationships in the pelvis in its native undisturbed state.

References

Mitsiopoulos N, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Lyons W, Gallagher D, Ross R. Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;85:115–122.

ElKhamary SM, Riad W. Three dimensional MRI study: safety of short versus long needle peribulbar anesthesia. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014;28:220–224.

Good MM, Abele TA, Balgobin S, Schaffer JI, Slocum P, McIntire D, et al. Preventing L5-S1 discitis associated with sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:285–290.

Pizzoferrato AC, Nyangoh Timoh K, Fritel X, Zareski E, Bader G, Fauconnier A. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging and pelvic floor disorders: how and when? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;181:259–266.

Varkarakis J, Sebe P, Pinggera GM, Bartsch G, Strasser H. Three-dimensional ultrasound guidance for percutaneous drainage of prostatic abscesses. Urology. 2004;63:1017–1020. discussion 1020.

Thompson JR, Gibb JS, Genadry R, Burrows L, Lambrou N, Buller JL. Anatomy of pelvic arteries adjacent to the sacrospinous ligament: importance of the coccygeal branch of the inferior gluteal artery. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:973–977.

Muir TW, Tulikangas PK, Fidela Paraiso M, Walters MD. The relationship of tension-free vaginal tape insertion and the vascular anatomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:933–936.

Ates M, Kinaci E, Kose E, Soyer V, Sarici B, Cuglan S, et al. Corona mortis: in vivo anatomical knowledge and the risk of injury in totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2016;20:659–665.

Stavropoulou-Deli A, Anagnostopoulou S. Corona mortis: anatomical data and clinical considerations. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:283–286.

Eisma R, Wilkinson T. From “silent teachers” to models. PLoS Biol. 2014;12, e1001971.

Trelles M, Eberhardt KM, Buchholz M, Schindler A, Bayer-Karpinska A, Dichgans M, et al. CTA for screening of complicated atherosclerotic carotid plaque – American Heart Association type VI lesions as defined by MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:2331–2337.

Barksdale PA, Elkins TE, Sanders CK, Jaramillo FE, Gasser RF. An anatomic approach to pelvic hemorrhage during sacrospinous ligament fixation of the vaginal vault. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:715–718.

Roshanravan SM, Wieslander CK, Schaffer JI, Corton MM. Neurovascular anatomy of the sacrospinous ligament region in female cadavers: implications in sacrospinous ligament fixation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:660.e1–660.e6.

Sivanesan K, Abdel-Fattah M, Ghani R. External iliac artery injury during insertion of tension-free vaginal tape: a case report and literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1105–1108.

Rehder P, Glodny B, Pichler R, Mitterberger MJ. Massive retropubic hematoma after minimal invasive mid-urethral sling procedure in a patient with a corona mortis. Indian J Urol. 2010;26:577–579.

Gobrecht U, Kuhn A, Fellman B. Injury of the corona mortis during vaginal tape insertion (TVT-Secur using the U-Approach). Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:443–445.

Drewes PG, Marinis SI, Schaffer JI, Boreham MK, Corton MM. Vascular anatomy over the superior pubic rami in female cadavers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2165–2168.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Interprofessional Center for Experiential Learning and Simulation (iCELS) of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in facilitating access to and use of the Invivo5 software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dueñas-Garcia, O.F., Kim, Y., Leung, K. et al. Vascular anatomical relationships of the retropubic space and the sacrospinous ligament, using three-dimensional imaging. Int Urogynecol J 28, 1177–1182 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3240-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3240-0