Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Several mesh repair systems for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) were introduced into clinical practice with limited data on safety, complications or success rates, and impact on sexual function. The Austrian Urogynecology Working Group initiated a registry to assess the use of transvaginal mesh devices for POP repair. We looked at perioperative data, as well as outcomes at 3 and 12 months.

Methods

Between 2006 and 2010 a total of 20 gynecology departments in Austria participated in the Transvaginal Mesh Registry. Case report forms were completed to gather data on operations, the postoperative course, and results at 3 and 12 months.

Results

A total of 726 transvaginal procedures with 10 different transvaginal kits were registered. Intra- and perioperative complications were reported in 6.8 %. The most common complication was increased intraoperative bleeding (2.2 %). Bladder and bowel perforation occurred in 6 (0.8 %) and 2 (0.3 %) cases. Mesh exposure was seen in 11 % at 3 and in 12 % at 12 months. 24 (10 %) previously asymptomatic patients developed bowel symptoms by 1 year. De novo bladder symptoms were reported in 39 (10 %) at 3 and in 26 (11 %) at 12 months. Dyspareunia was reported by 7 % and 10 % of 265 and 181 sexually active patients at 3 and 12 months postoperatively respectively.

Conclusions

The 6.8 % rate of intra- and perioperative complications is in line with previous reports. Visceral injury was rare. The 12 % rate of mesh exposure is consistent with previous series.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse may occur in up to 50 % of parous women and the life-time risk of surgery for symptomatic POP and incontinence has been estimated at 11 % [1, 2]. Because of presumed high failure rates of conventional surgical procedures, a number of so-called kits for transvaginal placement of alloplastic meshes were developed for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. These kits become available with limited data on their safety, complications or success rates, and have an impact on patients’ sexual function. To collect data on transvaginal mesh procedures, the Austrian Urogynecology Working Group initiated a registry for these operations in 2006. The aim was to assess the use of the transvaginal mesh devices for POP repair, perioperative management, as well as outcomes at 3 and 12 months.

Materials and methods

All 90 departments of gynecology in Austria were invited to participate in the Transvaginal Mesh Registry in 2006. Participating centers completed a case report form (CRF) for every mesh procedure. The CRF contained anonymized items regarding the personal data of the patient, previous pelvic floor surgery, bladder and bowel function disorders as well as dyspareunia. SUI, OAB, and residuals >50 ml were documented by a physician according to ICS/IUGA terminology. Concerning bowel function the patients were asked about increased effort when passing stool, anal incontinence, and urgency symptoms. Dyspareunia was documented as “yes,” “no” or “no intercourse.” Data were obtained on the operation itself, the immediate postoperative course, and outcomes at 3 and 12 months. In patients available for clinical follow-up we asked for information on reoperations, mesh exposure, urinary and bowel symptoms, and dyspareunia, as well as patient and physician satisfaction with the results of the operation. Institutional review board approval was not obtained because at the time of initiation of the registry it was not required for this type of study in Austria. The registry was closed at the end of 2010.

Data are presented as means and ranges for numerical variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. McNemar’s test was used to evaluate differences in categorical variables between baseline and follow-up at 3 and 12 months.

Results

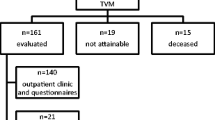

Twenty units in Austria entered data on a total of 726 patients operated on between 2006 and 2010. The mean age of the patients was 66 years (range 27–88) and mean BMI 26.8 (range 18.1–47.3). Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the patients, stage of prolapse, and bladder and bowel, as well as sexual symptoms. Overall, 357 patients (48 %) had undergone previous gynecological surgery, including 297 (41 %) with previous hysterectomy (Table 1). The 726 operations comprised more than 10 different transvaginal meshes (Table 2). 429 operations (59 %) were carried out as isolated procedures and 297 (41 %) in combination with other operations (Table 3). The most frequently performed concomitant operations were hysterectomy (n = 102; 14 %) and transobturator tape insertions (n = 47; 7 %).

Intraoperative and perioperative complications (n = 50, 6.8 %) are listed in Table 4. The most common complication was increased bleeding (16 cases, 2.2 %), following by bladder and bowel peroration. Subgroup analyses of patients undergoing vaginal mesh repair with concomitant hysterectomy (n = 102) compared with the group without concomitant hysterectomy (n = 624) showed statistically significantly more bowel perforation (2/0; p = 0.02). There were no statistically significant differences in bladder perforation (0/6; p = 0.600) and increasing bleeding (1/14; p = 0.708) One patient had injury of the internal iliac vein following insertion of Prolift mesh and received 26 units of packed red cells. The overall median postoperative stay was 6 days (range 2–20).

Overall, 398 patients (55 %) were available for clinical follow-up examination at 3 months and 231 (32 %) at 1 year. Mesh erosion/vaginal tape exposure was seen in 11 % at 3 months and 12 % at 1 year. 17 exposures seen at 1 year had been presented at 3 months. In 36 cases at 3 months and in 21 cases at 1 year mesh erosion was treated conservatively. Patients undergoing vaginal mesh repair with concomitant hysterectomy compared with the group without concomitant hysterectomy showed statistically significantly more mesh erosion/vaginal tape exposure at 3 months (21 vs 10 %; p = 0.003) and at 1 year (27 vs 9 %; p = 0.0004). Bladder, bowel, and sexual symptoms at 3 months and 1 year are shown in Table 5.

Patients with bowel problems preoperatively had statistically significant improvement of bowel symptoms (p < 0.001). Twenty-four (10 %) previously asymptomatic patients developed bowel symptoms by 1 year. Persistence of bowel symptoms was reported in 30 patients (8 %) at 3 months and in 14 patients (6 %) at 1 year. De novo bladder symptoms were reported by 39 patients (10 %) at 3 months and 26 (11 %) at 1 year. Persisting bladder symptoms were reported by 120 patients (30 %) at 3 months and by 71 (31 %) patients at 1 year. Improvement in bladder symptoms was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Dyspareunia was reported by 7 % and 10 % of sexually active patients at 3 months and 1 year.

At 3 months and 1 year patients and physicians were asked for their view regarding their satisfaction with the operation (Table 6). At 1 year 86 % of patients would have recommended the procedure and 81 of the physicians considered the results “excellent.”

Reoperations during the follow-up up to 1 year were reported in a total of 29 of the 231 patients available for follow-up (13 %). Indications were recurrent prolapse in 17 (7 %) ± removal of mesh in 10 (4 %), ± stress urinary incontinence operation in 10 (4 %) cases.

Discussion

We present data on 726 patients undergoing transvaginal mesh procedures for pelvic organ prolapse, including clinical follow-up on 398 patients at 3 months and 231 patients at 12 months. The literature on these procedures, perioperative management, complications, and short- and long-term outcome consists of a limited number of randomized trials and case series [1, 3–9]. Two similar registries from Great Britain and Scandinavia have been reported [7, 8].

Although only 20 of the 90 gynecology departments in Austria participated, 42 were performing vaginal mesh surgery. The registry contains about 70 % of the meshes placed between 2006 and 2010.

About half of the patients in the registry had undergone previous gynecological surgery including hysterectomy. 194 (27 %) patients had undergone previous surgery for prolapse, indicating that mesh kits were used in both primary and the recurrent setting. Similar rates of previous gynecological surgery were reported in the registries from Great Britain and Scandinavia [7, 8].

The 6.8 % rate of intraoperative complications in our registry is in line with published studies [4, 5, 7, 8]. The most common intraoperative problem was increased bleeding (16 cases, 2.2 %) followed by bladder perforation (6 cases, 0.8 %). Carey et al. reported in their randomized trials (n = 69) 1 case of significant intraoperative blood loss in a patient undergoing surgery with mesh devices [5]. In a series of 248 patients, Altman et al. reported 4.4 % with serious complications and 14.5 % with minor complications [8]. Abdel-Fattah et al. reported a 1.6 % bladder injury and 1.1 % rectal injury rate and 2 women with serious vascular injuries [7]. In our study 8 patients needed two or more blood products with four reoperations during the postoperative stay. Abdel-Fattah et al. reported injury of the right internal pudendal artery with posterior mesh [7]. The bladder and bowel perforation rate of 0.8 % and 0.3 % respectively in our study is consistent with previously reported data. In a randomized study Halaska et al. reported a 3.8 % bladder injury rate in the mesh group compared with 1.4 % with sacrospinous fixation [10]. In contrast, Carey et al. described one bladder perforation in the no mesh group [9].

Our series contains seven reoperations during the immediate postoperative stay because of urethral obstruction leading to new placement or partial excision of meshes. We have not found similar reports in the literature. The explanation for this might be that the anterior arms of the mesh under the bladder neck were placed too tightly. This complication was documented by four different departments and so does not seem to be a single-user problem.

We saw mesh erosion or exposure in 11 % and 12 % of patients at 3 months and 1 year respectively. A systematic review by Sung et al. reported graft erosion of 0–30 % [4]. Similar rates of mesh exposure have been reported by other authors (16 %, 14 %, 10 %) [1, 7, 10, 11]. We have no information on patients who were not seen for follow-up. Erosions have been described in almost all mesh studies, and many studies mention that conservative management is often disappointing [7, 9]. In our population 10 patients at 3 months and 4 at 1 year required reoperation under general anesthesia for partial/total excision of the mesh.

In our registry the rate of bladder and bowel symptoms improved from 57 % and 26 % preoperatively to 26 % and 6 % at 3 months, and 25 % and 5 % at 1 year respectively. Conversely, 24 previously asymptomatic patients developed bowel symptoms (difficult defecation, imperative bowel and/or incontinence) by the 1-year follow-up. Persistence of bowel symptoms was seen in 30 patients at 3 months and in 14 patients at 1 year. De novo bladder symptoms (residual volume <50 ml, clinical SUI, latent SUI and OAB) was reported in 39 at 3 months and 26 patients at 1 year. Halaska et al. reported 27 % and 9 % de novo SUI and de novo OAB rates in 79 patients treated with mesh for vaginal vault prolapse [10]. Menefee et al. documented a decrease in urinary symptoms severity using the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) in 99 patients treated with mesh or colporrhaphy for anterior vaginal wall prolapse [11]. Altman et al. reported a randomized trial with a 12.3 % rate of de novo stress urinary incontinence in patients treated with mesh kits for prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall [12].

Amongst the sexually active patients in our registry (66 % at 3 months and 78 % at 1 year), dyspareunia was reported by 7 % at 3 months and 10 % at 1 year. In these patients dyspareunia decreased significantly, but we have no information about the reasons for sexual inactivity and symptoms in women not seen for follow-up. Halaska et al. reported a similar frequency of dyspareunia in patients treated with mesh (9.1 % at 3 months and 8 % 1 year follow-up) [10]. Menefee et al. reported 2 cases of de novo dyspareunia in 33 patients treated with mesh, and resolution of dyspareunia symptoms in 12 patients who had dyspareunia preoperatively [11]. Carey et al. reported similar rates of de novo dyspareunia in women treated with or without mesh for vaginal repair (16 % and 15 % respectively) [9]. Our findings are in line with previously published data that in most cases vaginal mesh surgery does not seem to have an overall negative impact on sexual activity and dyspareunia [13].

Patient satisfaction with surgery was high (87 % and 86 % at 3 months and 1 year respectively). Physician satisfaction with anatomical results was somewhat lower (81 % at 3 months and 1 year), which is comparable with the results of Abdel-Fattah et al. and Fatton et al. [7, 14]

Eleven out of 726 patients (1.5 %) required reoperation in the initial postoperative period and 29 out of 231 (13 %) during follow-up up to 1 year. Recurrent prolapse occurred in 7 %, somewhat less frequently than reported by Nieminen et al. (13 % at 3 years) [15]. Menefee et al. reported 18 % recurrent prolapse in 33 patients treated with mesh at a minimum of a 2-year follow-up [11]. A systematic review by Maher et al. reported mesh repair to be associated with less recurrence of prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall than standard anterior repair [1].

Four per cent of patients underwent reoperation for SUI. Correction of prolapse could lead to unmasking of latent SUI. Overall, in prolapse surgery the value of the addition of a continence procedure to a prolapse repair in preoperatively asymptomatic women remains debated [1].

Our registry has a number of limitations. We have no control group. Data were collected voluntarily, and there was no monitoring for data verification. Although participating departments declared to register all procedures and complications, a potential bias for missed cases or incomplete data has to be considered. The patients who were seen in follow-up were not examined by independent observers. We have a drop-out rate of 45 % and 68 % at 3 months and 1 year follow-up respectively. Also, the use of mesh kits has decreased after an FDA notification and certain products assessed by our registry are no longer available. Nevertheless, data on complications are relevant as we will continue to see patients who have had these operations performed.

The strengths of our registry are the large number of procedures, the assessment of perioperative and postoperative data, as well as follow-up, up to 1 year. Regarding external validity there is an ongoing debate on the use and safety of vaginal mesh operations. Registries like ours, although imperfect, are an important tool for assessing these procedures. Data from registries are more likely to reflect “real life,” rather than results from studies carried out at tertiary referral centers. In this vein, over 90 % of all urogynecological procedures performed in Denmark are currently recorded in the Danish Urogynecological Database (Dugabase) [16]. This excellent percentage carries great potential for quality assessment and research in the future.

References

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Adams EJ, Hagen S, Gllazener CM (2010) Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 14(4):CD004014. doi:10.1002/1465185

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Collong JC, Clark AL (1997) Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 89:501–506

Sokol AI, Iglesia CB, Kudish BI, Gutman RE, Shveiky D, Bercik R, Sokol ER (2012) One-year objective and functional outcomes of a randomized clinical trial of vaginal mesh for prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2061(86):ee1–ee9

Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, Balk EM, Uhling K, Lau J, Abed H, for the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group et al (2013) Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair- a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 112:1131–1141

Carey M, Slack M, Higgs P, Wynn-Williams M, Cornish A (2007) Vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse using mesh and vaginal support device. BJOG 115:391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01606.x

McLennan GP, Sirls LT, Killinger KA, Nikolavsky D, Boura JA, Fischer MC, Peters KM (2012) Perioperative experience of pelvic organ prolapse repair with the Prolift and Elevate vaginal mesh procedure. Int Urogynecol J 24:287–294. doi:10.1007/s00192-012-1830-z

Abdel-Fattah M, Ramsay I, on behalf of the West of Scotland Study Group (2008) Retrospective multicenter study of the new minimally invasive mesh repair devices for pelvuic organ prolapse. BJOG 115(1):22–30

Altman D, Falconer CH, for the Nordic transvaginal mesh group (2007) Perioperative morbidity using transvaginal mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair. Obstet Gynecol 107(1):303–308

Carey M, Higgs P, Goh J, Leong A, Krause H, Cornish A (2009) Vaginal repair with mesh versus colporrhaphy for prolapse: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 116:1380–1386. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02254.x

Halaska M, Maxova K, Sottner O, Svabik K, Mlcoch M, Kolarik D, Mala I, Krofta L, Halaska J (2012) A multicenter, randomized, prospective, controlled study comparing sacrospinous fixation and transvaginal mesh in the treatment of posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 207(4):301, e1–7

Menefee SA, Dyer KY, Lukacz ES, Simsiman AJ, Luber KM, Nguyen JN (2011) Colporrhaphy compared with mesh or graft-reinforced vaginal parvaginal repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 118(6):1337–1344

Altman D, Väyrynen T, Engh ME, Axelsen S, Falconer C, Nordic Transvaginal Mesh Group (2011) Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. N Engl J Med 364(19):1826–1836

Sentilhes L, Bwerthier A, Sergent F, Verspyck E, Descamps P, Marpeau L (2008) Sexual function in women before and after transvaginal mesh placement for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 19:763–772

Fatton B, Amblard J, Debodinanace P, Cosson M, Jacqutin B (2007) Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift technique)- a case series multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 18:743–752

Nieminen K, Hiltunen R, Takala T, Heiskanen E, Merikari M, Niemi K, Heinonen PK (2010) Outcomes after anterior vaginal wall repair with mesh: a randomized, controlled trial with a 3 years follow up. Am J Obstet Gynecol 203:235, e1–235.e8

Guldberg R, Brostrom S, Hansen JK, Kaerlev L, Gradel KO, Norgard BL, Kesmodel US (2013) The Danish Urogynecological Database: establishment, completeness and validity. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 24:983–990

Acknowledgements

Participating investigators and centers: J. Angleitner, W. Stummvoll (deceased), Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Schwestern Linz; B. Abendteuer, K. Weghaupt, Landesklinikum Mostviertel Amstetten; M. Börecz, P. Klug, Landeskrankenhaus Judenburg; H. Stöger, D. Wagner, Allgemeinses Krankenhaus Linz; W. Neunteufel, E. Reinstadler, Krankenhaus Dornbirn; H.M.H. Hofmann, M. Konrad, Landeskrankenhaus Feldbach; G. Hartmann, E. Kosteritz, Landeskrankenhaus Gmunden; G. Ralph, G. Müller, Landeskrankenhaus Leoben; O. Preyer, Krankenhaus Göttliches Heiland Wien; A. Dungl, P. Riss, Landesklinikum Mödling; G. Wagner, Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder, Vienna; Stephan Kropshofer, Medical University of Innsbruck; M. Medl, Hanusch Krankenhaus; B. Dallinger, W. Dirschmayer, B. Schaffer, Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Schwestern Ried; A. Tammaa, H. Salzer, A. Mirna, P. Lozano, Wilhelminenspital Vienna, P. Roth, Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder St.Veit/Glan; K. Anzböck, LK Weinviertel Hollabrunn; Dz. Siljak, Landeskrankenhaus Salzburg.

We thank Fedor Daghofer, PhD, for the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest

Thomas Aigmueller: paid travel expenses (Ethicon, Gynecare)

Funding of the study

Database and statistical analysis were supported by the Austrian Urogyneology Working Group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bjelic-Radisic, V., Aigmueller, T., Preyer, O. et al. Vaginal prolapse surgery with transvaginal mesh: results of the Austrian registry. Int Urogynecol J 25, 1047–1052 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2333-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2333-x