Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The primary objective of this study was to compare outcomes of absorbable and permanent suture for apical support with high uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension (HUSLS). The secondary objective was to investigate the rate of suture erosion.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients who underwent HUSLS with delayed absorbable and primarily permanent suture. Apical support was calculated as a new variable: Percent of Perfect Ratio (POP-R). This variable measures apical support as the position of the apex in relation to vaginal length.

Results

At 1-year follow-up, there was no significant difference in apical support between the two groups. The number of patients who suffered from suture erosion in the cohort that received permanent suture was 11 (22%).

Conclusions

Permanent suture, in comparison with delayed absorbable suture, for HUSLS does not offer significantly better apical support at short-term follow-up. It is also associated with a high rate of suture erosion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension is a commonly performed surgical procedure for vaginal vault prolapse. The McCall’s culdoplasty described in 1957 used nonabsorbable sutures to obliterate the “redundant cul-de-sac of Douglas by a series of continuous sutures so as to suspend the vaginal apex by the uterosacral ligaments.” [1]. In 2000, Shull et al. described high uterosacral ligament suspension (HUSLS) in which three nonabsorbable sutures are placed in the ligament on either side and passed through the superior aspect of the transverse portion of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia [2]. Various modifications of this technique have been made, such as using different combinations of permanent and absorbable suture, either combined or used separately [3–5]. Using absorbable suture allows full-thickness bites to be taken compared with only the muscularis with permanent suture. On the other hand, absorbable suture may not allow enough vaginal cuff apposition to the uterosacral ligament before dissolution, which if true, would put the apical repair at risk of anatomic failure. Many surgeons who perform HUSLS use at least one permanent suture on each side. The primary objective of this study was to compare the apical support of two groups of patients who underwent HUSLS: one group with absorbable suture and the other with primarily permanent suture. The secondary objective was to investigate the rate of symptomatic suture erosion associated with the use of permanent suture within 1 year after surgery.

Materials and methods

After institutional review board approval was obtained, a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent HUSLS at a tertiary referral center between 2006 and 2009 was performed. Patients were analyzed at 6 months and 1 year after surgery. They were placed into two groups. Patients in group 1 received only absorbable suture for apical suspension, and those in group 2 received predominantly permanent suture. All procedures were supervised by one of two fellowship-trained urogynecologists. The standard technique was to perform a six-point high uterosacral apical fixation similar to the original description of the procedure [2]. When using permanent suture, it was routine to take the caudal-most uterosacral stitch (corresponding to the lateral-most stitch on the vaginal cuff) with delayed absorbable suture and the rest with permanent suture. In an attempt to reduce the incidence of suture erosion, care was taken while placing permanent sutures to avoid the vaginal epithelium. The only suture involving the vaginal epithelium was the most caudal suture. Suspension procedures were performed vaginally and laparoscopically. When they were performed laparoscopically, the same principles were applied. Choice of suture was not dependent on the extent of prolapse but the preference of the supervising surgeon. Cystoscopy was routinely performed at the time of surgery to assess ureteral patency. If no ureteral efflux was seen, cystoscopy was repeated after stitches were serially removed, starting with the distal-most stitch. Concomitant procedures such as midurethral slings and anterior and posterior colporrhaphy were performed as indicated.

Before surgery, each patient underwent a standardized urogynecologic interview and a complete physical examination. All patients underwent preoperative urodynamic assessment to determine the necessity for concomitant anti-incontinence procedure. Pelvic organ prolapse was quantified according to the International Continence Society’s Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system [6]. All patients pre- and postoperatively had pelvic examinations performed in a 45° upright position in a birthing chair while performing the Valsalva maneuver with maximal effort. A new variable was used to measure apical support: Percent of Perfect Ratio (POP-R), calculated as the percentage of cervix/cuff (C) to total vaginal length (TVL). This variable measures apical support as the position of C in relation to the TVL. It is derived by the formula, \( {\text{POP}} - {\text{R}} = - \left[ {\left( {\text{C}} \right)/{\text{TVL}}} \right] \times {1}00\% \). Highest apical support, where C = -(TVL) will have the highest POP-R value (100%).

On postoperative visits, patients were assessed for suture erosion by systematic inspection of the vaginal cuff, and suture erosion was noted as present or absent. Patients were noted to be symptomatic if they suffered from spotting, persistent discharge, or dyspareunia. Patients with symptomatic suture erosion were treated conservatively with vaginal estrogen cream. Those who did not respond to conservative management underwent trimming of exposed sutures in the office. Continuous variables were summarized using mean [standard deviation (SD)] and compared using Student’s t tests. Categorical variables were summarized using count (%) and compared using Fisher’s exact tests.

Results

Of 115 patients who underwent the HUSLS procedure in the study period, 65 (56.5%) were in group 1 and 50 (43.5%) in group 2. All patients in group 1 received polydioxanone (PDS, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) sutures. Among patients in group 2, 38 (76%) received a combination of braided permanent polyester suture (Ti•cron™, Convidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) and polydioxanone and 12 (24%) received a combination of polyester (Ethibond™) and polydioxanone. Except for history of previous anti-incontinence surgeries, both groups had similar preoperative demographic characteristics and are shown in Table 1.

Intraoperative data comparing the two groups are shown in Table 2. Concomitant hysterectomy was performed in 57 (87.7%) patients in group 1 and 39 (78.0%) patients in group 2. Routes of hysterectomy included vaginal, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal, total laparoscopic, and abdominal. Two patients in group 1 underwent trachelectomy. Most suspension procedures in both groups were performed via the vaginal approach. The two groups were similar in other intraoperative characteristics, including the number of sutures placed on each uterosacral ligament, operating time, blood loss, and concomitant surgeries. Routine intraoperative cystoscopy revealed three (4.6%) patients in group 1 and five (10%) in group 2 with ureteral compromise caused by the uterosacral ligament stitch. This was identified and corrected intraoperatively.

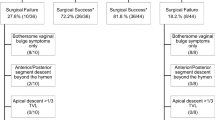

Forty-four (67.7%) patients in group 1 and 38 (76%) in group 2 followed for their 6-month visit (p = 0.407) (Fig. 1). At 6-month follow-up (Table 3), the POP-R value for group 1 was 93.7% (9.8) and for group 2 92.6% (9.4; p = 0.607). Thirty-eight (58.5%) patients in group 1 and 21 (42%) in group 2 followed up for their 1-year postoperative visit (p = 0.093) (Fig. 1). At 1-year follow-up (Table 3), the POP-R value for group 1 was 83.5% (25.2) and for group 2 89% (15.7; p = 0.368). A post hoc power analysis revealed that this study had 99% power to detect a 10% difference at the 6-month visit. A subanalysis revealed that there were no significant differences between characteristics of patients lost to follow-up and those who followed up at 1 year (results not shown).

To eliminate some of the bias introduced by inclusion of multiple routes of surgery, a subanalysis comparing only vaginally performed suspension procedures was performed (Table 4). Again, there were no statistically significant differences between groups.

The number of patients with symptomatic suture erosion within 1-year postoperatively was 11 (22%). Of these, nine (18%) underwent suture excision in the office within a 1-year postoperative period. All patients with suture erosions received braided polyester suture. There were no cases of asymptomatic suture erosions.

Discussion

Although HUSLS was initially described using permanent suture, use of absorbable suture has been associated with excellent clinical outcome. Wong et al. describe their case series of uterosacral suspension using PDS sutures, where, at median follow-up of 12 months, anatomic and symptomatic failure rate was 7% [7]. Natale et al. reported 4.4% failure rate of USLS using polyglactin (Vicryl) suture with 12 months of follow-up [8]. It is likely that the apical support is derived from scarring of the vaginal apex to the uterosacral ligament and does not depend on suture longevity.

Although case series described in the literature demonstrate the efficacy and low adverse effect profile associated with absorbable suture for HUSLS, comparative studies are lacking and are needed. This study demonstrates that incorporation of permanent suture at the time of performing uterosacral ligament vaginal suspension does not provide better apical support at short-term follow up. In addition, it was associated with an erosion rate of 22%. This is lower than the 44.6% suture erosion rate described in the literature using similar suture [9].

One of the strengths of this study is the unique and novel method used to address apical support. The pelvic organ prolapse grading system is limited in grading apical prolapse. A significant prolapse of the apex can still be a stage 1 and a prolapse of only 2 cm of the anterior or posterior vaginal wall is a stage 2. The variable POP-R not only considers the position of the apex but also its relation to the TVL. Best possible C value for a patient with a short TVL is high compared with one with a long TVL. In order to eliminate the effect of TVL on the C value, it is important to consider both the C and TVL when apical support is being evaluated. The variable POP-R has never been used before and is not validated. However, validation of this tool is a planned follow-up project. Another strength of the study is strict adherence to surgical technique regardless of whether it was done vaginally or laparoscopically. Choice of suture was not dependent on the extent of prolapse but the preference of the supervising surgeon. One of the supervising surgeons prefers to use absorbable sutures and the other uses a combination of permanent and absorbable sutures.

One of the major limitations of the study is that the number of patients in each group was small and were evaluated over a short period of time. Long-term follow-up to determine long-term results is planned. Polydioxanone dissolves at an average of 90 days and is completely absorbed at 6 months. After the suture is completely dissolved, the vaginal support is indicative of scarring of the vagina with the uterosacral ligaments, which will potentially remain in place. After 6 months, it is unlikely that permanent suture has any benefit over the scarring that remains in place. This study is also limited by relatively poor follow-up. Another weakness is the retrospective design. Our findings may have to be confirmed by a prospective randomized controlled trial.

In summary, permanent suture, in comparison with delayed absorbable suture, for HUSLS does not offer significantly better apical support at short-term follow-up. It is also associated with a high rate of suture erosion.

References

Mc CM (1957) Posterior culdeplasty; surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy; a preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol 10:595–602

Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ (2000) A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:1365–1373, discussion 73-4

Barber MD, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL, Bump RC (2000) Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site-specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:1402–1410, discussion 10-1

Silva WA, Pauls RN, Segal JL, Rooney CM, Kleeman SD, Karram MM (2006) Uterosacral ligament vault suspension: five-year outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 108:255–263

Karram M, Goldwasser S, Kleeman S, Steele A, Vassallo B, Walsh P (2001) High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension with fascial reconstruction for vaginal repair of enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:1339–1342, discussion 42-3

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K et al (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:10–17

Wong MJ, Rezvan A, Bhatia NN, Yazdany T (2011) Uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension using delayed absorbable monofilament suture. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct

Natale F, La Penna C, Padoa A, Agostini M, Panei M, Cervigni M (2010) High levator myorraphy versus uterosacral ligament suspension for vaginal vault fixation: a prospective, randomized study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 21:515–522

Yazdany T, Yip S, Bhatia NN, Nguyen JN (2010) Suture complications in a teaching institution among patients undergoing uterosacral ligament suspension with permanent braided suture. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 21:813–818

Conflicts of interest

Patrick J. Woodman, speaker for Pfizer, has received research grant from Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology. Douglass S. Hale, consultant for Ethicon Women’s Health and Urology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kasturi, S., Bentley-Taylor, M., Woodman, P.J. et al. High uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension: comparison of absorbable vs. permanent suture for apical fixation. Int Urogynecol J 23, 941–945 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1708-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1708-0