Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Information about the natural history of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is scarce.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study of 160 women (mean age 56 years), whose answers in a population-based survey investigation indicated presence of symptomatic prolapse (siPOP), and 120 women without siPOP (mean age 51 years).

Results

Follow-up questionnaire was completed by 87%, and 67% underwent re-examination according to pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) system after 5 years. Among re-examining siPOP women, 47% had an unchanged POP-Q stage, 40% showed regression, and 13% showed progression. The key symptom “feeling of a vaginal bulge” remained unchanged in 30% of women with siPOP, 64% improved by at least one step on our four-step rating scale, and 6% deteriorated. Among control women, siPOP developed in 2%. No statistically significant relationship emerged between changes in anatomic status and changes in investigated symptoms.

Conclusion

Only a small proportion of women with symptomatic POP get worse within 5 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is one of the most common indications for surgery in women. In the USA alone, POP is estimated to lead to over 250,000 surgical procedures per year [1]. Prolapse surgery is frequently undertaken on non-imperative indications based on the assumption that the condition is likely to worsen over time. However, the scientific information about the natural history of POP-associated symptoms and pelvic support defects are scarce. Some loss of vaginal support is common and is seen in 43–76% of women presenting for routine gynecological care [2, 3], but the prognosis of mild POP is unknown. Mild prolapse has been claimed to be a fluid state where prolapse is not always progressive as traditionally thought and spontaneous regression can occur [4–6]. In addition, some symptoms associated with POP are non-specific and only weakly associated with anatomical measurements [7–9].

The purpose of this study was to prospectively investigate changes in pelvic support and symptom development, as well as the relationship between these respective parameters in a cohort of mostly non-seeking women with symptoms indicative of prolapse (siPOP), with or without verifiable anatomical defects at time of entry.

Materials and methods

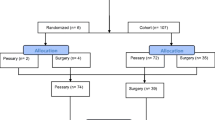

This prospective observational study proceeded from a population-based cross-sectional survey investigation of the age-specific prevalence of symptomatic prolapse in the Stockholm female population [10]. An outline of the study design and subject accrual is shown in Fig. 1.

All women were asked to complete a validated short form questionnaire, which predicted the presence of observable POP with reasonable accuracy [11]. Discriminant criteria divided women into those who were predicted to have prolapse (henceforth referred to as having siPOP) and those who were not. The questions and the algorithm for classification have been elaborated in a previous paper [11]. Briefly, the symptom “feeling of a vaginal bulge” carried almost all of the discriminatory ability of the instrument; reports of the presence of this symptom (often/sometimes/infrequently) were sufficient for being classified as having siPOP. In the absence of this symptom, a combination of the symptoms “vaginal pain/discomfort” (often), “worsening upon heavy lifting,” “need of manual reduction of the anterior vaginal wall” (often/sometimes/infrequently), and urge incontinence (often/sometimes/infrequently) could also lead to a siPOP classification, but no women reported this combination, and in practice, all had a feeling of a vaginal bulge. From the total of all women in the respective strata, 206 with and 206 without siPOP were randomly selected to be invited for a gynecological examination. The participation rates in this phase of the investigation were 162 (78.6%) and 120 (58.3%). Subsequently, two attending women were excluded because their identities did not match with those of the invitees.

The cohort in the present follow-up study thus consisted of 280 women, 160 with scores indicative of siPOP and 120 women whose answers indicated absence of siPOP. They were all gynecologically examined according to the POP quantification system (POP-Q) [12] between February 2002 and March 2003 at Södersjukhuset, Stockholm [13].

After approximately 5 years, the 280 women again received the same short form questionnaire supplemented with questions about body weight, height, any changes in obstetric, gynecological, or medical history, and bowel habits. They were also invited to a renewed pelvic examination.

Both the initial examinations and the re-examinations were done according to POP-Q with the women in dorsal lithotomy position and with empty bladder. All measurements, except total vaginal length, were taken during maximal Valsalva maneuver as described by Bump et al. [12]. The gynecologists were blinded to the questionnaire responses and to the results of any previous examination. The re-examinations were performed by a single examiner who had not done any of the initial examinations. In order to calibrate the POP-Q assessments, the first ten patients were jointly examined together with the previous examiners. The interobserver variation was minimal. Anatomical assessments of POP-Q stage were then transformed to categorical “indices of change” (no change, progression, regression). The five symptoms asked for in the questionnaire were feeling of a vaginal bulge, vaginal discomfort, aggravation of symptoms by heavy lifting, urge urinary incontinence, and need for manual reduction to complete bladder emptying. We had also added a question about stress urinary incontinence. The response alternatives were “yes often,” “sometimes,” “infrequently,” and “never.” In analyses of symptom prevalence rates, symptoms were coded in a dichotomous fashion (present/absent) considering the responses “yes often” or “sometimes” as indicative of presence of the symptom. Change in symptoms was then categorized as continued presence (present→present), disappeared (present→absent), new (absent→present), and continued absence (absent→absent). In order not to miss more subtle changes, we also took advantage of all four response alternatives and considered a change of at least one step in the direction of higher frequency as “worsening of symptoms,” at least one step in the other direction as “improvement of symptoms,” while “no change of symptoms” was reserved for those who gave identical answers in both questionnaires.

Finally, since surgery most likely changed the natural history and we did not have information about the status at time of surgery, we performed worst-case-scenario sensitivity analyses. In these analyses, all 23 women who had undergone surgery for POP, surgery for incontinence, or both during follow-up were considered to have progressed in POP-Q stage and deteriorated in terms of symptoms.

Statistical methods

Statistical comparisons of POP-Q stage and reported symptoms were performed using Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, McNemar's test, and the sign test when appropriate. All tests were two-sided and the level of significance was 0.05. We made no adjustments for multiple testing. The proportions of women at follow-up with improvement of or unchanged symptoms of feeling a vaginal bulge were calculated together with 95% confidence intervals. The study was approved by the ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet, and all women provided informed consent.

Results

Study population

One hundred forty-one women (88%) with siPOP and 102 (85%) non-siPOP women completed the postal questionnaire at follow-up. A total of 116 (72%) of those with siPOP and 72 (60%) of those without attended the 5-year follow up examination between November 2007 and June 2008. Mean follow up time between examinations was 5.6 years (SD 0.3; range 4.8–6.2). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Drop-outs (n = 37) were on average younger (mean age 51.8 years) and had fewer births (median 1).

Fourteen (10%) of the 141 responding siPOP women had undergone surgery for POP, six (4%) for incontinence, and one (1%) for both POP and incontinence during the follow-up period. Five (4%) of the women with siPOP reported a hysterectomy. Among women who did not meet our criteria for siPOP, two (2%) were operated on for incontinence, but none underwent hysterectomy or surgery for POP. Twelve women (five with siPOP and seven without) had a delivery during follow up. Three of the seven non-siPOP women had had no deliveries before.

Development of symptoms (n = 243)

Table 2 describes the prevalence of symptoms at entry and at end of follow up in all 243 women who answered the questionnaire on both occasions, by siPOP status at entry. Among siPOP women, the prevalence of most prolapse symptoms decreased significantly, while no corresponding change was observed among non-siPOP women. However, the prevalence of stress urinary incontinence decreased in the latter group.

Because pelvic floor surgery performed between entry and end of follow-up is likely to have affected the symptomatology, we recalculated the change in prevalence of symptoms among siPOP women, assuming that these symptoms would have been present in operated women had the surgical intervention not occurred. Accordingly, the hypothetical end prevalence of the symptom “feeling of a vaginal bulge” at follow up was estimated at 35% (p < 0.001 compared to baseline), “vaginal discomfort” 31% (p = 0.441), and “worsening of symptoms with heavy lifting” 40% (p = 0.654).

We additionally studied changes in occurrence of the key symptom “feeling of a vaginal bulge” using the full resolution of our rating scale (never, infrequently, sometimes, often). This analysis was again confined to the 141 women who were initially classified as having siPOP and who answered the questionnaire twice. Figure 2 shows the frequency distribution of individual changes. While women with no change constituted 30% (95% CI 22–37), more women reported a reduction of symptoms (64%, 95% CI 56–72) than an increase (6%, 95% CI 2–10). A similar analysis among women not fulfilling our criteria for siPOP showed that 91% reported no change, while 7% had experienced an increase.

The frequency distribution of individual changes in the key symptom of vaginal bulging among women with symptoms indicative of symptomatic prolapse (siPOP) (n = 141). Zero on the x-axis denotes no change, −1 means a change of one step in the direction of less symptoms, and +1 represents a one-step change in the direction of more symptoms

Development of POP-Q stage (n = 188)

Two determinations of POP-Q stage were done in a total of 188 women. Among the 188, 10 (5%) had undergone prolapse surgery during follow up (all with siPOP at entry), eight (4%) surgery for incontinence (six with siPOP and two without), and one (0.5%) both types of surgery. Three of the siPOP women had undergone hysterectomy during follow up. At baseline, 22 (12%) were nulliparous (15 with siPOP and seven without). Only parous women reported additional deliveries (four with siPOP and two without).

Table 3 shows the distributions of POP-Q stages at entry and at the 5-year follow up examination, by siPOP status at entry. Mean age at entry for women with stage 0 was 42.6 years (range 30–62;SD 8.7), stage I 54.1 years (range 31–77;SD 11.4), stage II 55.1 years (range 33–76;SD 12.3), stage III 64.1 years (range 51–79;SD 9.7), and stage IV 72.0 years (range 65–77;SD 5.6). At the 5-year follow-up examination the POP-Q distribution in the siPOP group had shifted towards less advanced stages (p < 0.0001; sign test). A less marked, and statistically non-significant (p = 0.743; sign test), shift was noted among non-siPOP women. The difference between stages 0 and I in POP-Q is subtle and of clinically questionable significance, and possibly liable to observer bias, while we repeated these analyses after combining stage 0 and I (data not shown). The shift towards less advanced stages remained significant both among women initially classified as having siPOP (p = 0.007; sign test) and among the 72 who did not fulfill our criteria for siPOP (p = 0.027; sign test).Of the women who initially fulfilled our criteria for siPOP, 47% (95% CI 38–57) had the same stage after 5 years as they had at entry. Both progression and regression had occurred, although regression (40%, 95% CI 31–49) was more common than progression (13%, 95% CI 7–19). Among women with POP-Q stage I at entry, 44% were found to no longer have prolapse (stage 0) at follow-up, while 24% had advanced to stage II. Women with stage II at entry remained within the same stage in 58%, whereas 29% showed regression and 13% progression. No progression was noted in the 13 women who had POP-Q stage III at entry, but in 10 of them, a reduction of the POP-Q stage had occurred. Only four women had stage IV initially; two underwent surgery during follow up and the remaining two were deemed to have stage III at follow-up. In a sensitivity analysis, we assumed that women, who had pelvic floor surgery in the follow-up period, would have had POP-Q stage IV at follow up if left unoperated. Even with this extreme assumption, regression was more common than progression.

Relation between changes in POP-Q stage and changes in symptom presentation

We further cross-tabulated changes in POP-Q stage (regression, stable, progression) over the 5-year period against changes in selected pelvic floor symptoms (dichotomized as present or absent) (Table 4). This analysis included all 188 women who answered the questionnaire and attended the gynecological examinations both at entry and at follow up. No statistically significant associations were found between changes in POP-Q stage and changes in reported symptoms. The results were similar in age strata <45 and ≥45 years, in an analysis restricted to women with siPOP at entry (data not shown), and in a sensitivity analysis excluding women who had undergone POP and/or incontinence surgery after entry into the cohort.

Discussion

This prospective study proceeded from a population-based survey investigation that probed into symptoms consistent with POP using a questionnaire with high specificity [11]. We followed a stratified random sample of participating women—mostly non-consulting—who reported symptoms of such quality and severity that presence of prolapse was deemed likely, and 98% of them, indeed, had anatomic prolapse of POP-Q stage I or higher (although a less impressive 75% had stage II or higher). For comparison, we also followed a sample of the women whose questionnaire answers were not indicative of any prolapse. In the latter group, 66% still had POP-Q stage I or higher, but only 17% had stage II or higher. This allowed us to investigate the 5-year natural history among women with symptoms indicative of POP—a group for which treatment strategies remains a matter of debate—and to study the relationship between changes in anatomic prolapse and changes in symptoms. Only a minority of women with symptoms indicative of symptomatic prolapse reported symptom aggravation over time, and a larger proportion reported improvement. We observed no significant association between changes in POP-Q status and changes in symptoms.

Our findings that mild to moderate prolapse is a dynamic condition in which spontaneous regression can occur is largely consistent with those of the few studies on this topic published to date [5, 6], although the participants in these studies were older and postmenopausal. A simple cross-sectional view on our data at entry clearly indicated that there was a strong positive association between age and POP-Q stage, women with stage 0 or I were considerably younger and those with stage III and IV substantially older than women with stage II. This is seemingly at odds with our prospective observations and might inspire speculations about birth cohort effects. While some birth cohort effects—reflecting general improvements in obstetric care over time—cannot be excluded, it must be emphasized that a small proportion of the studied women, in fact, did show progression.

Regression toward the mean must be considered as an explanation for the counterintuitive general tendency to get better rather than worse over time. When individuals are selected because of extreme values (high or low) of a measurement (e.g., self-reported symptoms), the resulting group will consist partly of individuals whose true values are genuinely extreme, and partly of people whose values just happened to be extreme at the time of measurement because of intra-person biological variation or due to a chance fluctuation. Upon re-measurement, individual values that were unusually extreme by chance alone will tend to be more typical (less extreme). As a consequence, the whole group originally selected will exhibit a less extreme average on re-testing. Our siPOP women were selected based on “extreme” symptom status (presence of symptoms), not on POP-Q stage; hence, the net effect in the entire study group should be liable to regression toward the mean in regard to symptoms but not in regard to POP-Q stage, yet we observed a net flux toward lower stages.

Another concern is observer bias, since the first and second examinations were done by different gynecologists. Attempts to calibrate the assessments, and the observed minimal inter-observer variation, somewhat allay these concerns. Moreover, after combining stages 0 and I, thus basing our analysis entirely on the rather robust classification of stages II−IV, we still observed a tendency towards improvement in the group with siPOP. In summary, we cannot confidently exclude regression toward the mean and observer bias, although these flaws are unlikely to explain all of the symptomatic and anatomic improvements.

For a high proportion of the women with a stage II prolapse at enrollment, the prolapse remained stable. Growing evidence suggests that vaginal descent to the hymenal ring, POP-Q stage II, or greater, represents an important cut off point for symptom development, particularly feeling of a vaginal bulge symptoms [7, 14, 15]. Nonetheless, women who had POP-Q stage II and symptoms of bulging initially reported less such symptoms (p < 0.001) at follow up. It is conceivable that some women become adapted to their symptoms and fail to report them unless they progress.

The major strength of this investigation is the prospective study design and the basis in a population-based sample that also included non-consulting women with mild to moderate prolapse. Although population-based studies involving both consulting and non-consulting women may be advantageous in studies aimed at understanding the biology of the disease, our data should not be uncritically generalized to patients who present to health care. It is important to emphasize that our results cannot be generalized to the entire population with anatomic POP or to the women with an asymptomatic POP.

In conclusion, our 5-year longitudinal study of women with symptoms indicative of mild to moderate POP suggests that the condition is fluid, with transitions both to the better and to the worse, the former seemingly more common than the latter. Unfortunately, symptoms constitute a poor guide in the identification of women at high risk for rapid deterioration.

References

Subak LL, Waetjen LE, van den Eeden S, Thom DH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS (2001) Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 98:646–651

Swift SE (2000) The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:277–285

Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svardsudd KF (1999) Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 180:299–305

Bland DR, Earle BB, Vitolins MZ, Burke G (1999) Use of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse staging system of the International Continence Society, American Urogynecologic Society, and Society of Gynecologic Surgeons in perimenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181:1324–1327, discussion 1327–8

Bradley CS, Zimmerman MB, Qi Y, Nygaard IE (2007) Natural history of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol 109:848–854

Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, Gold E, Robbins J (2004) Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190:27–32

Ellerkmann RM, Cundiff GW, Melick CF, Nihira MA, Leffler K, Bent AE (2001) Correlation of symptoms with location and severity of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:1332–1337, discussion 1337–8

Burrows LJ, Meyn LA, Walters MD, Weber AM (2004) Pelvic symptoms in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 104:982–988

Bradley CS, Zimmerman MB, Wang Q, Nygaard IE (2008) Vaginal descent and pelvic floor symptoms in postmenopausal women: a longitudinal study. Obstet Gynecol 111:1148–1153

Tegerstedt G, Maehle-Schmidt M, Nyren O, Hammarstrom M (2005) Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in a Swedish population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 16:497–503

Tegerstedt G, Miedel A, Maehle-Schmidt M, Nyren O, Hammarstrom M (2005) A short-form questionnaire identified genital organ prolapse. J Clin Epidemiol 58:41–46

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K et al (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:10–17

Miedel A, Tegerstedt G, Maehle-Schmidt M, Nyren O, Hammarstrom M (2008) Symptoms and pelvic support defects in specific compartments. Obstet Gynecol 112:851–858

Swift SE, Tate SB, Nicholas J (2003) Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: what is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:372–377, discussion 377–9

Barber MD (2005) Symptoms and outcome measures of pelvic organ prolapse. Clin Obstet Gynecol 48:648–661

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miedel, A., Ek, M., Tegerstedt, G. et al. Short-term natural history in women with symptoms indicative of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 22, 461–468 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1305-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1305-z