Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is considered to be the first-line treatment for female stress urinary incontinence (SUI). There are few studies that have tested the efficacy of unsupervised PFMT. The aim of this study was to compare the effectiveness of intensive supervised PFMT to unsupervised PFMT in the treatment of female SUI.

Methods

Sixty-two women with SUI were randomized to either supervised or unsupervised PFMT after undergoing supervised training sessions. They were evaluated before and after the treatment with the Oxford grading system, pad test, quality of life questionnaire, subjective evaluation, and exercise compliance.

Results

After treatment, there were no differences between the two groups regarding PFM strength (p = 0.20), International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form score (p = 0.76), pad test (p = 0.78), weekly exercise compliance (p = 0.079), and subjective evaluation of urinary loss (p = 0.145).

Conclusions

Both intensive supervised PFMT and unsupervised PFMT are effective to treat female SUI if training session is provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines stress urinary incontinence (SUI) as involuntary urine leakage upon effort, exertion, sneezing, or coughing [1]. SUI is the most common type of urinary incontinence (UI) and is reported by approximately 50% of incontinent women [2]. SUI can affect women of all ages and has an overall prevalence of 10-30% in girls and women between the ages of 15 and 64 years [3]. Despite the scarce research data available in Brazil, prevalence is estimated to be around 35%, but only 59% of the affected women seek medical support [4]. SUI is a distressing disorder that has a major impact on a woman’s quality of life, interfering with social, professional, and family activities [5].

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) constitutes a low-cost conservative treatment, which is currently regarded as the first-line treatment for women with SUI [6]. Success rates of 56-75% have been reported [7, 8]. PFMT leads to hypertrophy of muscle fibers, enhanced cortical awareness of muscle groups, strengthening of connective tissue in the muscles, and more effective recruitment of active motor neurons. It has been suggested that increasing the power and tone of the pelvic floor muscles leads to permanent elevation of the levator plate to a higher resting position inside the pelvis, thereby 'lifting' the pelvic viscera and restoring normal reflex activity and other protective continence mechanisms [9]. PFMT is effective and represents the least invasive option for treating SUI. Also important is the absence of side effects associated with pelvic floor exercises; thus, these exercises are the only method with no restrictions for any patient [10].

Success with PFMT is hampered by non-adherence, which is related to factors such as inability to contract the pelvic floor muscles and lack of motivation [11]. Thus under supervision by a physical therapist, PFMT has the potential of improving adherence to training and has been demonstrated to be more effective when compared to unsupervised PFMT [12–17].

However, some studies evaluating unsupervised PFM training did not assess the patient’s ability to contract the PFM before prescribing the exercises [13, 17]. Other studies investigated the ability to contract the PFM with a 1-h demonstration program followed by one supervised session [14, 15]. As the patient’s perception of the ability to contract the PFM can influence adherence to training, this approach could have changed the results.

Considering the high prevalence of UI together with the high costs of treatment and the low socioeconomic level of some countries, the investigation of the efficacy of unsupervised programs is relevant both to the health system and to symptomatic women because such programs demand less time and money. Therefore, we designed a study to compare the effectiveness of PFMT that is intensively supervised by a physical therapist to unsupervised PFMT in the treatment of SUI.

Materials and methods

From March 2006 to October 2007, women with confirmed urodynamic stress urinary incontinence were selected to participate in this randomized trial. The study was conducted following the Ethical Research Ethics Committee guidelines of the Federal University of Minas Gerais including an informed consent provided by all patients involved in the investigation.

A standardized assessment at enrollment included a urogynecological history, urodynamic study, quality of life questionnaire (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form; ICIQ-SF) and 24-h pad test. Subjects were required to have urodynamic stress urinary incontinence with Valsalva leak point pressure more than 60 cm/H2O and no detrusor overactivity. All subjects had predominant symptoms of SUI with an average of at least three stress incontinence episodes per week. Additional major exclusion criteria included chronic neurological or muscular diseases, abnormal genital bleeding, genital prolapse at stage ≥2 of POP-Q [18], active genitourinary tract infections, pregnancy, and women who preferred surgery. Patients with intrinsic sphincter deficiencies as identified by Valsalva leak point pressure ≤60 cm H20 measured in the sitting position with a volume of 250 ml in the bladder were also excluded from the study.

Once enrolled by a physician investigator, patient groups underwent supervised training sessions. In the first session of training, to allow the participants to learn how to perform muscle contraction and encourage conscious pre-contraction in physical stress situations, a urogynecology physiotherapist provided subjects with instructions on anatomy and PFM function. Both groups were taught to contract the pelvic floor muscles correctly, and success with contracting the muscle was assessed by vaginal palpation. All participants were encouraged to contract the PFM as strongly as they could. After the first session, the physiotherapist trained the patients in the study protocol, which consisted of ten contractions held for 6 s and relaxing for 12 s in the following positions supine, lateral, sitting, and standing totaling 90 contractions.

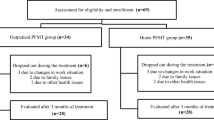

Seventy-eight patients were initially selected; of these, 16 were excluded from the study. Five of the excluded women were eliminated because they were not able to perform correct pelvic floor contraction or were graded <2 by the Modified Oxford Scale. The other 11 patients declined to participate in the study.

Once proper contractions were confirmed, the remaining 62 women were randomly assigned to two distinct groups: supervised PFMT group and unsupervised PFMT group. Allocation of the groups was undertaken using a computer-generated random number generator. Two women in the supervised PFMT (6%) and one (3%) woman in the unsupervised PFMT were unable to comply with the treatment or return visits and were subsequently excluded.

Treatment protocol

The duration of the PFMT protocol was 8 weeks and maximum PFM contraction was required in both horizontal and vertical positions. In the first week, 90 contractions a day were performed, and in the following 7 weeks, 180 contractions a day were performed. The contraction time prescribed for both groups was the same: 6 s of sustained contraction and 12 s of PFM relaxation. At least nine exercise series were performed. The degree of difficulty varied according to the patient’s position: lying on the back, on the side and face down, sitting, and standing.

The supervised PFM training group did the PFMT in a group with two weekly sessions of 50 min each and was aided by verbal instructions given by a physiotherapist. Participants were instructed to perform the protocol daily at home and received figures containing the positions as well as the number of contractions and the sustaining times. They were encouraged to observe the frequency at which they performed home exercises because this information would be collected after treatment.

The unsupervised PFMT group followed the same protocol as the supervised PFMT group. However, exercises were performed solely at home on a daily basis for a period of 8 weeks without supervision by a physical therapist. These participants were only aided by figures containing positions as well as contraction number and sustaining time. They were also instructed to contract the PFM as strongly as possible. Adverse events and adherence to all treatments were registered in a training diary updated by the physical therapist in charge of the sessions during each clinic visit.

Outcome measurements

At the initial visit, all subjects underwent a complete medical history and physical examination, including evaluation of the function of the pelvic floor using the Oxford grading system and a 24-h pad test [15, 19]. The Oxford grading system consists of digital palpation during a maximal voluntary contraction and evaluates muscle strength. Based on this score, the patients are then classified in grades ranging from 0 to 5 (Fig. 1) [19]. All study subjects were also asked to complete the validated ICIQ-SF [20]. The ICIQ-SF consists of three items (“Frequency”, “Amount”, and “Impact”) plus a group of eight questions related to the type of UI, which are not part of the questionnaire score. The only purpose of the eight questions is to provide a description and to serve as a guide to the type of urinary incontinency. The total score is the sum of the first three items and ranges from 0 to 21 points. A score of 21 represents the worst possible quality of life, and 0 represents the best possible quality of life [20]. Methods, definitions, and units conformed to the standards proposed by the International Continence Society [1].

The primary outcome measurement was objective improvement or cure of stress incontinence based on a negative 24-h pad test (<2 g in weight). Secondary outcome measurements included ICIQ-SF and pelvic floor muscle strengthening. A subjective SUI cure was measured by a simple question about how the patient felt about her incontinence problem after treatment. The response options available were “cured”, “better”, “unchanged”, or “worse”.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using a statistical analysis package (SPSS 16.0 Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A pilot study was conducted with ten patients in each group to establish the sample size. The sample size allowed a difference of 2.9 points in quality of life with a standard deviation = 4.35, β = 0.20, α = 0.5. Considering a power test of 80% and a significance level of 5%, we concluded that the sample size should be 60 patients with 30 in each group. To test the normal distribution of data in each group, the Shapiro Wilk test was used. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t test (age, body mass index (BMI), and infant birth weight), Mann-Whitney test (education, parity, duration of symptoms, leak point pressure, number of sessions performed before the protocol, PFM strength, quality of life, amount of urine loss, and weekly exercise compliance), and chi-square test (subjective evaluation of urinary loss) as appropriate. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

At baseline, there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of demographics, clinical characteristics, or outcome measurements such as age, BMI, parity, duration of symptoms, vaginal deliveries, weight of babies, pad test, impact of symptoms on quality of life, Valsalva leak point pressure, voiding diary, or muscle strength (Tables 1 and 2). The only difference between the general characteristics of the groups was education level. This variable was assessed considering the number of years the women attended school. In the supervised group, the patients had more years of school.

Primary outcome measurement

There was a significant decrease in the pad weight in both groups (Table 2). There was no significant difference between groups (p = 0.78). A negative pad test was observed in 36.6% of subjects in the supervised PFMT group and in 34.5% of patients in the unsupervised PFMT group.

Secondary outcome measurements

Results of the ICIQ-SF are shown in Table 2. After 8 weeks, the quality of life increased significantly in both groups. No significant difference was identified between groups (p = 0.57; Table 2).

Subjectively, 70% and 69% of the women in the unsupervised and supervised treatment groups, respectively, claimed to be satisfied and did not desire a different treatment after the 8-week study treatment period. The subjective evaluation of urinary loss was also similar between groups after treatment (p = 0.145; Fig. 2).

In both groups, there was significant improvement in muscle strength as measured by the Oxford scale, before and after treatment (Table 2).

The weekly exercise compliance did not differ between supervised and unsupervised PFMT groups (p = 0.079). In the present study, compliance with weekly home exercises was similar in both groups with a frequency observed of four times a week for the supervised PFMT group and five times a week for the unsupervised PFMT group. The prescribed frequency for home treatment was seven times a week for both groups.

Discussion

In this study, unsupervised individual home training was shown to be as effective as PFMT under supervision for the short-term treatment of female SUI. We observed improvements in PFM strength, symptoms impact on QOL, amount of urine loss and subjective evaluation of urinary loss in both groups, and there was no statistical difference between the groups in those variables.

Our findings do not agree with our initial expectation of better results for the supervised group and with other studies [13, 14]. Bo et al. found that after PFMT 60% of the supervised group and 17.3% of the home-exercise group reported to be continent or almost continent (p < 0.01), only the supervised group demonstrated significant reduction in urine loss on the pad test. The authors concluded that the results of PFMT for female SUI are highly dependent of the frequent supervision by a therapist [13]. Konstantinidou et al. compared the effect of group PFMT under intensive supervision to that of individual home application of the same set of exercises. They found a significant benefit in favor of supervised pelvic muscle training, although significant improvements were noted in both groups [14].

We believe that our results are different because both groups underwent supervised training sessions before randomization. We decided to do training sessions to make the sample as homogenous as possible when the study began to decrease problems related to adherence of treatment. It is well known that the reasons why treatment fails and patients abandon treatment include inability to perform the exercises and incorporate them into their routine as well as lack of knowledge of PFM therapy [11]. Therefore, during the training sessions, we gave explanations and answered questions about the anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract. We corrected inappropriate contractions and we motivated and enhanced adherence to treatment. As demonstrated in our outcome measurements, the weekly exercise compliance did not differ between the groups in our study.

The amount of urine loss assessed by the pad test showed significant reduction in both groups. The pad test was negative in 36.6% of subjects in the supervised PFMT group and in 34.5% of patients in the unsupervised PFMT group. Our results are in agreement with reports in the literature, which have shown expected rates of cure/improvement in the short-term range from 27% to 90% [15, 21]. Most studies fail to report cure and improvement rates separately, and it is likely that improvement in symptoms is a more common outcome than complete dryness.

ICIQ-SF, which was used in this study, is a validated questionnaire and is recommended by ICS for clinical research due to its high confidence level. All of the studied patients had improvements in quality of life that did not differ between the groups. One of the important aspects analyzed was the patients’ self-reported improvement. Patients’ self-assessment of their condition is considered of primary importance. Subjectively, 70% and 69% of the women in the unsupervised and supervised treatment groups, respectively, claimed to be satisfied. These data are similar to previous reports. In randomized controlled trials, 70% of the patients reported improvement in SUI after PFMT [6].

The limitations of our study are short follow-up time and the analysis of pelvic floor muscle function and strength. A valid and reproducible measurement is very difficult to obtain, although objective evaluation such as perineometry and transperineal ultrasound should help us understand the correlation between pelvic floor muscle strength and urine loss [22, 23]. The use of a scale based on the sensitivity of fingers introduced in the patient’s vagina during the contraction of the pelvic muscles (digital palpation) is a very common procedure in diagnosis and analysis of urogynecological dysfunctions. Despite its subjective nature, the modified Oxford scale is a useful diagnostic tool; additionally, it is cheap and very simple to perform. However, it is strongly dependent on training and experience [24].

According to a Cochrane review, PFMT should be recommended in first-line conservative management programs for SUI [6]. Our results are very important because we demonstrated in a randomized control trial that for patients with SUI the first choice of treatment can be a conservative treatment in their home without the supervision of a physiotherapist. Of course, patients must have some sessions with a physiotherapist to learn how to correctly contract the PFM. Unsupervised therapy has the advantages of low cost to the public health system and to the patient, it increases the number of women who can benefit from the treatment and women can easily adapt the treatment to personal circumstances.

In conclusion, supervised pelvic floor muscle training and unsupervised pelvic floor muscle training appear to be equally effective for improving female SUI if training session is provided.

References

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U et al (2002) Standardization Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardization Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 21:167–178

Ortiz C (2004) Urinary stress incontinence in the gynecological practice. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 86(Suppl 1):S6–S16

Fantl JA, Bump RC, Robinson D, McClish DK, Wyman JF (1996) Efficacy of estrogen supplementation in the treatment of urinary incontinence: the Continence Program for Women Research Group. Obstet Gynecol 88:745–749

Guarisi T, Pinto-Neto AM, Osis MJ, Pedro AO, Costa-Paiva LH, Simões F (2001) A procura de serviço médico por mulheres com incontinência urinária. RBGO 23:439–443

Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S, Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trøndelag (2000) A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: the Norwegian EPINCONT study. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trøndelag. J Clin Epidemiol 53:1150–1157

Hay-Smith E, Bø K, Berghmans L, Hendriks H, deBie R, van Waalwijk et al (2007) Pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD 001407

Freeman RM (2004) The role of pelvic floor muscle training in urinary incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 111:37–40

Castro RA, Arruda RM, Zanetti MR, Santos PD, Sartori MG, Girão MJ (2008) Single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no active treatment in the management of stress urinary incontinence. Clinics 63:465–472

Bø K (2004) Pelvic floor muscle training is effective in treatment of female stress urinary incontinence, but how does it work? Int Urogynecol J 15:76–84

Bø K, Talseth T, Holme I (1999) Single blind, randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones and no treatment in management of genuine stress incontinence in women. Br Med J 318:487–493

Alewijnse D, Mesters I, Metsemakers J, Adriaans J, van den Borne B (2001) Predictors of intention to adhere to physiotherapy among women with urinary incontinence. Health Educ Res 16:173–186

Alewijnse D, Mesters I, Metsemakers J, van den Borne B (2003) Predictors of long-term adherence to pelvic floor muscle exercise therapy among women with urinary incontinence. Health Educ Res 18:511–524

Bø K, Hagen RH, Kvarstein B, Jørgensen J, Larsen S (1990) Pelvic floor muscle exercise for the treatment of female urinary stress incontinence: III. Effects of two different degrees of pelvic floor muscle exercises. Neurourol Urodyn 9:489–502

Konstantinidou E, Apostolidis A, Kondelidis N, Tsimtsiou Z, Hatzichristou D, Ioannides E (2007) Short-term efficacy of group pelvic floor training under intensive supervision versus unsupervised home training for female urinary stress incontinence: a randomized pilot study. Neurourol Urodyn 26:486–491

Wilson PD, Al Samarrai T, Deakin M, Kolbe E, Brown AD (1987) An objective assessment of physiotherapy for female genuine stress incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 94:575–582

Wong KS, Fung BKY, Fung LCW, Ma S (1997) Pelvic floor exercises in the treatment of urinary stress incontinence in Hong Kong Chinese women. In: Abstracts from the 27th Annual Meeting of the International Continence Society. Yokohama, pp 62–63

Ramsay IN, Thou MA (1990) A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises in the treatment of genuine stress incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 9:398–399

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:10–17

Laycock J, Whelan MM, Dumoulin C (2008) Patient assessment. In: Haslam J, Laycock J (eds) Therapeutic management of incontinence and pelvic pain, 2nd edn. Springer, London, p 62

Tamanini JT, Dambros M, D’Ancona CA, Palma PC, Rodrigues-Netto N Jr (2005) Responsiveness to the Portuguese version of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire - Short Form (ICIQ-SF) after urinary stress incontinence surgery. Int Braz J Urol 31:482–489

Kegal AH (1951) Physiologic therapy for urinary stress incontinence. JAMA 146:915–918

Thompson JA, O’Sullivan PB, Briffa NK, Neumann P (2006) Assessment of voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction in continent and incontinent women using transperineal ultrasound, manual muscle testing and vaginal squeeze pressure measurements. Int Urogynecol J 17:624–630

Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bourbonnais D, Gravel D, Lemieux MC (2004) Pelvic floor maximal strength using vaginal digital assessment compared to dynamometric measurements. Neurourol Urodyn 23:336–341

Saleme CS, Rocha DN, Del Vechio S, Pinotti M (2009) Mechanical simulator for the levator ani. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Biomédica 25:123–130

Conflicts of interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Felicíssimo, M.F., Carneiro, M.M., Saleme, C.S. et al. Intensive supervised versus unsupervised pelvic floor muscle training for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized comparative trial. Int Urogynecol J 21, 835–840 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1125-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1125-1