Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate pelvic organ support during pregnancy and following delivery. This was a prospective observational study. Pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POPQ) examinations were performed during each trimester of pregnancy and in the postpartum. Statistical comparisons of POPQ stage and of the nine measurements comprising the POPQ between the different time intervals were made using Wilcoxon’s signed rank and the paired t-test. Comparison of POPQ stage by mode of delivery was made using Fisher’s exact test. One hundred thirty-five nulliparous women underwent 281 pelvic organ support evaluations. During both the third trimester and postpartum, POPQ stage was significantly higher compared to the first trimester (p<0.001). In the postpartum, POPQ stage was significantly higher in women delivered vaginally compared to women delivered by cesarean (p=0.02). In nulliparous pregnant women, POPQ stage appears to increase during pregnancy and does not change significantly following delivery. In the postpartum, POPQ stage may be higher in women delivered vaginally compared to women delivered by cesarean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parity is believed to be an important risk factor in the development of pelvic organ prolapse [1, 2, 3]. Most studies evaluating the pelvic floor during pregnancy and following delivery focus on the impact of delivery on urinary or anal incontinence, with less attention to pelvic organ support [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Furthermore, many of these studies assessing the impact of delivery on the pelvic floor only include a single antepartum examination, usually in the third trimester, with the assumption that this represents “normal.” Our understanding of the natural history of pelvic organ support over the course of pregnancy is limited.

The relationship between parity and the development of pelvic organ prolapse has been studied using the POPQ in a general gynecologic population [3]. Gravidity, parity, number of vaginal deliveries, and vaginal delivery of a macrosomic infant have all been shown to be associated with increased POPQ stage. One study has used the POPQ during pregnancy comparing exams between the third trimester and 6 weeks postpartum [9].It is unclear from either of these studies, however, whether pregnancy or the delivery process contributed to higher POPQ stage postpartum. The purpose of this study was to objectively document pelvic organ support during each trimester of pregnancy and at the postpartum visit in a population of nulliparous women.

Materials and methods

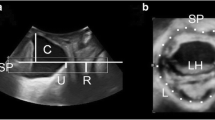

This was an Institutional Review Board approved prospective observational study conducted in an active-duty obstetrics clinic at Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA, USA. Nulliparous pregnant women were considered eligible at any point during their care. Women were excluded if they had preterm labor, bleeding, prior pelvic surgery, a known collagen vascular disorder, any other pregnancy complication that precluded vaginal examination, or if they declined exam. Whenever possible, evaluations were performed during each trimester and at the postpartum visit. First trimester was defined as 12 weeks or less, second trimester as 13–28 weeks, and third trimester as 29 weeks or greater. Demographic information including age, race, and gestational age were recorded at each evaluation along with POPQ stage and the nine POPQ points: Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp, PB, GH, D, C, and TVL. All POPQ examinations were performed as previously described [10].For women returning for postpartum evaluations, mode of delivery, infant weight, and length of second stage of labor were recorded. Descriptive statistics were used to report demographics, delivery information, and the POPQ stage proportions for each trimester and the postpartum. In women who underwent serial examinations, paired statistical comparisons of POPQ stage and the nine POPQ points were made between the first and third trimesters, third trimester and postpartum, and first trimester and postpartum. POPQ stage was compared using Wilcoxon’s signed rank test, and the nine POPQ component measurements were compared using the paired t-test. Comparison of POPQ stage and mode of delivery was made using Fisher’s exact test. Significance was set at 5%. Statistical analysis was preformed with Statview 4.5 (SAS, Berkley, Calif., USA). A subset of the antepartum data in this study has been published in two separate reports [10, 11].

Results

One hundred thirty-five nulliparous pregnant women attending an active-duty obstetrics clinic between November 2000 and February 2003 agreed to participate. Fifty-five percent were Caucasian, 29% African-American, 11% Hispanic, and 5% Asian. The mean age was 22 years (range: 18–38 years). A total of 281 examinations were performed, 86 during the first trimester (5–12 weeks), 58 in the second trimester (13–28 weeks), 75 in the third trimester (29–40 weeks), and 62 postpartum (5–22 weeks). Of 135 participants, 53 had one exam, 36 had two exams, 28 had three exams, and 18 had four exams. Statistical comparisons were made in exam pairs: first trimester vs third trimester (n=44 exams), first trimester vs postpartum (n=40 exams), and third trimester vs postpartum (n=52 exams) using Wilcoxon’s signed rank test for POPQ stage and the paired t-test for the individual POPQ points.

The overall distribution of POPQ stage for each trimester is depicted in Fig. 1 and is as follows: first trimester (15% stage 0, 84% stage 1, <1% stage 2), second trimester (0% stage 0, 81% stage 1, 19% stage 2), third trimester (1.3% stage 0, 60% stage 1, 39% stage 2), and postpartum (0% stage 0, 64.5% stage 1, 35.5% stage 2). Comparison of POPQ stage for each time interval revealed a significantly higher POPQ stage in both the third trimester and postpartum compared to the first trimester (p<0.001). POPQ stage did not differ significantly between the third trimester and postpartum (p=0.627). This difference was due to a higher proportion of POPQ stage 2 exams in both the third trimester and postpartum.

Consistent with the findings in overall POPQ stage, points Aa, Ba, Ap, and Bp (anterior and posterior vaginal wall measurements) showed significant descent relative to the hymen in the third trimester and the postpartum compared to the first trimester (p<0.001) and did not differ between the third trimester and postpartum. Interestingly, both PB (perineal body measurement) and GH (genital hiatus) increased significantly in the third trimester compared to the first trimester. In the postpartum, however, PB was similar to the first trimester measurement and GH was significantly larger than both first and third trimester measurements. The apical measurements, C (leading edge of the cervix) and D (posterior cul-de-sac), also showed significant decent relative to the hymen in the postpartum compared to the first trimester. The total vaginal length (TVL) however, was increased between the first and third trimesters but similar to the first trimester in the postpartum. Of all the POPQ points, only TVL and PB were similar to first trimester measurements in the postpartum. The individual POPQ point measurements for all 281 exams are shown in Table 1. The comparison of POPQ points between time intervals is shown in Table 2.

Finally, statistical comparison was made among the 62 postpartum exams by mode of delivery using Fischer’s exact test. There was a significantly higher proportion of POPQ stage 2 exams in women delivered vaginally (spontaneous and forceps combined) compared to those delivered by cesarean (p=0.02). Of the 13 women delivered by cesarean, only 1 (7.6%) was POPQ stage 2, while 43% of the 49 women delivered vaginally were POPQ stage 2. Interestingly, 54.5% of the women delivered by forceps had POPQ stage 2 exams, but this was not statistically significant compared to women delivered spontaneously (p=0.07). There were too few women in the postpartum group to make meaningful statistical comparisons between forceps delivery or any of the other delivery variables such as infant weight or length of second stage.

Discussion

Pregnancy produces significant physiologic alterations in virtually all organ systems but little is known about the normal changes in the pelvic floor during pregnancy. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether pregnancy itself or factors associated with labor and delivery contribute to the injury of the pelvic floor thought to result from parity [3]. In this study, several antenatal changes persisted following delivery, most notably descent of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls relative to the hymen. The overall increase in POPQ stage that was observed in the third trimesters and postpartum, compared to the first trimester, was primarily due to descent of point Aa which corresponds to the approximate location of the urethrovesical crease [12].

Several of the changes that occurred prior to delivery are likely normal physiologic changes and may be secondary to hormonally induced alterations in collagen [13, 14]. Most notable was the increase in the perineal body (PB). In addition, genital hiatus (GH), total vaginal length (TVL), and the posterior cul-de-sac (D) measurements were increased in the third trimester compared to the first. These interestingly had no impact on final POPQ stage assignment. Point C appeared to be influenced as early as the first trimester and did alter the POPQ stage assignment in this trimester, as noted in our earlier report [11]. Point C was responsible for an “upstaging” from stage 0 to stage 1 in 57% of the women with otherwise normal support in the first trimester and accounted for the lower than expected number of POPQ stage 0 exams early in the study.

There were several changes that may be a result of the delivery process, rather than the pregnancy itself. Both points C and D had significantly more descent relative to the hymen following delivery. There was also a significantly higher proportion of POPQ stage 2 exams noted in women delivered vaginally compared to those delivered by cesarean. Sze et al. performed POPQ examinations at 36 weeks gestation and at 6 weeks postpartum in 94 young nulliparous women and concluded that POPQ increased during the second stage of labor [9].In contrast, we found a higher proportion of POPQ stage 2 exams in the third trimester, prior to delivery. Also in contrast to the study by Sze et al., we did observe a statistically significant increase in POPQ stage in women delivered vaginally compared to those delivered by cesarean.

A weakness of this study was that a larger number of women could not be recruited and that more serial measurements could not be obtained. This study was originally designed as an observational study, and therefore lacked sufficient power to adequately assess the impact of delivery. A strength of this study is the relatively homogeneous characteristics of the patient population. This exclusively nulliparous, active-duty population was ideal for studying the influence of pregnancy on pelvic organ support by eliminating the effect of risk factors such as parity, advancing age, and obesity [15]. Finally, this study remains unique in that serial evaluations during pregnancy included first trimester POPQ measurements.

The etiology of pelvic organ prolapse has long been attributed to parity, but the degree to which it is influenced by pregnancy, labor, or delivery remains unclear. The natural history of prolapse and the differentiation of normal from abnormal pelvic organ support are not well described. Although stage 0 is considered to be “normal” support, POPQ stage 2 during the third trimester of pregnancy may not necessarily be pathologic. In this study, we used the POPQ staging system to describe pelvic organ support during each trimester of pregnancy and in the postpartum. We have found that POPQ stage increases during pregnancy, does not change significantly following delivery, but may differ in the postpartum based on mode of delivery. These findings illustrate the importance of considering pregnancy itself as a risk factor in the development of pelvic floor disorders.

References

Mant J, Painter R, Martin V (1997) Epidemiology of genital prolapse: observations from the Oxford Family Planning Association Study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 104:579–585

Samuelson EC, Victor FTA, Tibblin G, Svardsudd KF (1999) Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 180:299–305

Swift SE (2000) The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:277–285

Peschers U, Schaer G, Anthuber C, Delancey JO, Schuessler B. Changes in vesical neck mobility following vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 88:1001–6.

Meyer S, Schreyer A, DeGrandi P, Hohlfeld P (1998) The effects of birth on urinary continence mechanisms and other pelvic floor characteristics. Obstet Gynecol 92:613–618

Fynes M, Donnelly VS, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C (1998) Cesarean delivery and anal sphincter injury. Obstet Gynecol 92:496–500

Chaliha C, Kalia V, Stanton SL, Monga A, Sultan AH (1999) Antenatal prediction of postpartum urinary and fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 94:689–694

Meyer S, Hohlfeld P, Achtari C, Russolo A, De Grandi P (2000) Birth trauma: short and long term effects of forceps delivery compared with spontaneous delivery on various pelvic floor parameters. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 107:1360–1365

Sze EHM, Sherad III GB, Dolezai JM (2002) Pregnancy, labor, delivery, and pelvic organ support. Obstet Gynecol 100:981–986

O’Boyle AL, Woodman PJ, O’Boyle JD, et al. (2002) Pelvic organ support in nulliparous pregnant and nonpregnant women: a case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:99–102

O’Boyle AL, O’Boyle JD, Ricks RE, Patience TH, Calhoun BC, Davis GD (2003) The natural history of pelvic organ support in pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J 14:46–49

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:10–17

Landon CR, Crofts CE, Smith AR, Trowbridge EA (1990) Mechanical properties of fascia during pregnancy: a possible factor in the development of stress incontinence of urine. Contemp Rev Obstet Gynaecol 2:40–46

Jackson SR, Avery NC, Tarlton JF, Eckford SD, Abrams P, Bailey AJ (1996) Changes in metabolism of collagen in genitourinary prolapse. Lancet 347:1658–1661

Swift SE, Pound T, Dias JK (2001) Case-control study of etiologic factors in the development of severe pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 12:187–192

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defense. Reprints will not be available

Editorial Comment: The authors have performed a perspective observational study on pregnant women and performed POPQ examinations in each trimester and postpartum. The POPQ stage differed significantly between the first and third trimesters and between the first trimester and postpartum. No change was observed between the third trimester and postpartum. The mode of delivery was also recorded and there was no significant change in the POPQ examination of patients who delivered vaginally as compared to cesarean section. However, all the patients who underwent a cesarean section were in labor and the numbers are fairly low. The authors conclude that pregnancy itself is a risk factor in the development of pelvic floor disorders. This study is limited by its size and by the fact that an examination was not done in each trimester of the pregnancy in order to assess the progression of the pelvic floor disorder. It is however an interesting and useful study that may affect the debate on elective cesarean section for the prevention of pelvic floor disorders.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Boyle, A.L., O’Boyle, J.D., Calhoun, B. et al. Pelvic organ support in pregnancy and postpartum. Int Urogynecol J 16, 69–72 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-004-1210-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-004-1210-4