Abstract

This study documents that the survival of start-ups is central in explaining the relationship between entry and regional employment growth. Distinguishing between start-ups according to the period of their survival shows that the positive effect of new business formation on employment growth is mainly driven by those new businesses that are strong enough to remain in the market for a certain period of time. This result is especially pronounced for the relationship between the surviving start-ups and employment growth in incumbent businesses indicating that there are significantly positive indirect effects of new business formation on regional development. We draw conclusions for policy and make suggestions for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Aims and scope

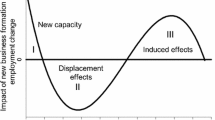

New businesses can contribute to employment growth in a number of ways. Most empirical analyses of the employment effects of start-ups focus on the jobs that are generated in the new entities, which may be labeled their direct effect.Footnote 1 However, new business formation may also have several types of indirect effects on the incumbent businesses (see Fritsch 2013, for a detailed exposition). One such indirect effect is the displacement of incumbent suppliers by the newcomers. A second type of indirect effect is improvement on the supply side of the economy due to additional competition by the entries. These supply-side improvements raise economic productivity and may induce higher competitiveness and more employment.Footnote 2

A number of studies have documented an on average positive effect of new business formation on economic development (for an overview see Fritsch 2013). In this paper, we want to explore the effects of new business formation on employment further by focusing on the role of the quality of start-ups. Our indicator for the quality of start-ups is their time of survival in the market. We analyze whether start-ups that survive for a certain period of time have a different effect on employment than those new businesses that exit relatively quickly. Assuming that those new businesses that survive constitute a particular challenge for incumbents, their indirect effects—especially the induced supply-side improvements—should be considerably larger than those of entries that fail (Falck 2007, 2009).

Our empirical analysis is based on data for West German regions for the 1975–2002 period. We investigate the employment effects of new business formation at a regional level for two reasons. First, an analysis at the level of industries leads to serious difficulties in interpreting the results in that industries may have a life cycle (Klepper 1996) that is characterized by a high number of entries in the early stages when the industry is growing, and a rather low number of entries in later stages during which the industry declines. In such a setting, the positive correlation between the start-up rate and the development of the industry in subsequent periods can hardly be regarded as evidence for a positive effect of entry on growth but it may be more appropriate to view entry as a symptom of industry development.Footnote 3 Second, the regional perspective is particularly relevant for policy since measures that aim at stimulating new business formation are in most cases directed towards regions, not industries.

The following section (Section 2) introduces the data and describes the spatial framework of the analysis. In Section 3, we derive the measures for the contribution of new and young businesses as well as of incumbents to employment change. Section 4 explains the empirical approach. Results of the empirical analysis are presented in Section 5. We summarize the results and draw conclusions for policy as well as for further research in Section 6.

2 Data and spatial framework of analysis

Our data are derived from the Establishment History Panel of the German Social Insurance Statistics. This data set covers all private-sector establishments except those that have no employees subject to obligatory social insurance payments (Spengler 2008).Footnote 4 The data allow us to follow employment in cohorts of newly founded businesses over time. The spatial framework of our analysis is based on the planning regions (Raumordnungsregionen) of West Germany. Planning regions consist of at least one core city and the surrounding areas. The advantage of planning regions compared to districts (Kreise) is that they can be regarded as functional units in the sense of travel to work areas, thereby accounting for economic interactions between districts (for the definition of planning regions and districts, see Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning 2003). We restrict our analysis to the 1976 to 2002 time period since the industry classification was changed for later years. However, the data allows us to track the survival of individual businesses beyond 2002.

The analysis is limited to West Germany and does not include East Germany for two reasons. First, while data on start-ups for West Germany are available for a quite long time period (1976–2002), the time series for East Germany is much shorter, beginning only in the year 1993. Second, many studies show that the developments in East Germany in the 1990s were heavily shaped by the transformation process to a market economy and, therefore, this part of the country is a rather special case that should be analyzed separately (e.g., Kronthaler 2005). The Berlin region was excluded due to changes in the definition of that region after the unification of Germany in 1990.

3 Definition of measures for employment growth

We divide overall employment change in the number of full-time employees in the private sector (\({\Delta }Emp_{total}\)) into two components as proposed by Fritsch et al. (2010): employment change in newly founded businesses (\({\Delta }Emp_{new}\)) and employment change in incumbents (\({\Delta }Emp_{inc}\)), i.e.,

Using the information on total employment change (\({\Delta }EMP_{total}\)) and on employment in new and young businesses (\({\Delta }EMP_{new}\)), we calculate the employment change of incumbents as

This employment change in incumbent businesses encompasses the indirect effects of the new businesses—displacement and supply-side effects—as well as other influences that are not caused by the start-ups.

Since other studies (for an overview, see Fritsch 2013) suggest that the effect of new businesses on employment evolves over a period of up to 10 years, we determine the employment that is directly created in the new businesses by summing the employment in the surviving start-ups that occurred within the previous decade, the periods \(t =-\)11 to \(t=\) 0. It is important to note that the figures used for calculating the rate of employment change in incumbent businesses are based on an identical group of businesses. This allows to avoid that employment change in incumbents is driven by businesses that have been classified as new businesses in \(t\)-1 and as incumbents in year \(t=\) 0. The respective measure for employment change in new and young businesses, however, is affected by changes in the population of observations because in \(t\)-1 the previous 10 (\(t\)-1 to \(t\)-11) entry cohorts are included, while the information on employment in new and young businesses in \(t=\) 0 also includes the cohort of the current year (\(t=\) 0 to \(t\)-11). Finally the employment change in incumbent and new and young businesses is weighted with the respective share in total employment. As a result the sum of employment change in incumbent businesses and in new and young businesses yields overall employment change (see Fritsch and Noseleit 2012b, for a more detailed description). Due to this weighing procedure the estimated coefficients for employment change in new and young businesses and for employment change in incumbents can be directly compared in order to assess their relative importance. Table 1 gives an overview of the definitions of the employment growth measures.

Since the definition of new and young businesses refers to those businesses established by the previous 10 entry cohorts, the calculated employment change measures are available for the 1987 to 2002 period. During this period, the major share, on average around 77 percent of total employment, was in incumbent businesses, while about 23 percent of employees worked in businesses that had been set up in the previous 10 years.

4 Variables and estimation approach

To analyze the relationship between new business formation, survival and employment growth, we regress total employment change, employment change in new and young businesses, and employment change in incumbent businesses on the average start-up rate of long- and short term survivors of the previous 10 years. We calculate start-up rates using the labor market approach, i.e., the number of new businesses per period is divided by the number of persons (in thousands) in the regional workforce at the beginning of the respective period. To control for the fact that the composition of industries not only varies considerably across regions but that the relative importance of new and incumbent businesses also varies systematically across industries, we calculate a sector-adjusted start-up rate.The sector-adjusted number of start-ups is defined as the number of new businesses in a region that would be expected if the composition of industries was identical across all regions. Thus, the measure adjusts the original data by imposing the same composition of industries on each region (for details, see the Appendix of Audretsch and Fritsch 2002). To analyze the relevance of new business survival for regional employment change we calculate start-up rates based only on those new and young businesses that have been in existence for a certain period of time (long-term survivors) and start-up rates based only on new and young businesses that exited during the first years after they were set up (short-term survivors).

The relationship between the different measures of employment change and entrepreneurial activity is specified as

where \(Y_{r,t}\) is the respective employment change (overall/in incumbents/in new and young businesses) in region \(r\), \(\mu _{r}\) is a region-specific fixed effect, \(\lambda _{t}\) represents a time fixed effect, and \(X_{r,t-1}\) are the other exogenous variables. LSR and SSR represent the start-up rates for the long- and short-term survivors respectively. The lagged start-up rates are calculated as a moving average over a period of 10 years in order to allow for the time lag identified in previous analyses (Fritsch 2013). Because our main interest is to compare the relation of new business formation to employment change in young businesses and in incumbents, the two start-up rates are the key independent variables in our model. Since we use the logarithm of the start-up rates, the coefficients can be interpreted as quasi-elasticities and, thus, allow easy comparisons between the regressions. These coefficients represent the relative employment change in incumbent and in new/young businesses that can be explained by the long-term start-up activity.Footnote 5

As further control variables we include the share of employees with a tertiary degree as a proxy for human capital, population density (logarithm of total population over area size in km\(^{2})\), a Harris-type market potential function (see Redding and Sturm 2008; Südekum 2008), and industry shares of 18 out of 19 private industries (see Peneder 2002; Fritsch and Noseleit 2012b) We apply fixed effects panel regression in order to control for unobserved region-specific characteristics.

We expect a positive coefficient for the start-up rate in models with total employment change and with employment in young and newly founded businesses as the dependent variable. In models intended to explain employment change in incumbent businesses, the coefficient of the start-up rate indicates the direction and magnitude of indirect employment effects. If the relationship of new business formation and employment change in incumbents is negative, displacement of incumbent employment likely dominates. If positive supply-side effects prevail, the coefficient of the start-up rate should be positive. Should the jobs in the young and newly founded businesses be the only contribution of start-ups to regional employment or if positive and negative indirect effects are of about the same magnitude, the coefficient is expected to be non-significant. By comparing the coefficients for start-up rates of long- and short-term survivors across the models with employment change in incumbents and in new and young businesses as dependent variables, we can assess the relative magnitude of direct and indirect relationships between new business formation and regional growth and its dependence on new business survival.

Table 2 provides summary definitions for the independent variables used in the analysis. Table 6 in the Appendix depicts descriptive statistics and Table 7 shows correlation coefficients for the statistical relationships between the variables.

5 Results

The choice of the survival threshold, i.e. the number of years that a firm has to survive in order to be classified a long-term survivor, is arbitrary. On the one hand, survival of start-ups over an only relatively short period of time may not be sufficient to indicate a certain quality and a significant challenge to the incumbents. On the other hand, applying a longer survival threshold and classifying all start-ups that exited the marked before the required number of years may not be justified for a considerable share of these businesses. The choice of the survival threshold has also implications for the statistical analysis. Because start-up rates for very short-lived entries are in some regions based on rather small numbers, the choice of a relatively short survival threshold (e.g. 1 year) may lead to rather erratic values. However, since each additional year of the survival threshold results in a reduction of years with available information in our data set, this time period should not be too long.

We chose a 4 year survival threshold for several reasons. First, since nearly 39 percent of all new businesses exit within the first 4 years, the respective numbers should be large enough to exclude erratic values of start-up rates for short-term survivors. Second, there is good reason to assume that firms that survived the first 4 years have succeeded to establish in the market and are no longer subject of a ‘liability of newness’ (Brüderl and Schüssler 1990).Footnote 6 Third, comparing start-up rates for different survival thresholds, we find the highest variation across regions for the 4 year survival rate indicating a particular relevance of the 4 year threshold. Empirically, the exact definition of the survival threshold is not that critical since the results of a threshold of three, four, and 5 years are highly correlated. Table 3 presents the results for total employment growth, employment growth in incumbent businesses, and employment growth in new and young businesses.

Models I, II and III of Table 3 consider only the start-up rate of long-term survivors, models IV, V, and VI include only the start-up rate of short-term survivors, and models VII, VII, and IX present results including both, start-up rates of short- and long-term survivors.

Looking at the effect of start-ups that survived at least 4 years on overall employment growth (Model I in Table 3), we observe a positive and significant relationship with a coefficient that is almost about the same size as the magnitude reported in earlier research employing a start-up rate computed with all entries (compare Fritsch and Noseleit 2012b). The relationship between the start-up rate of long-term survivors and employment growth in incumbent businesses (Model II) turns out to be much more pronounced than the relation between long-term survivors and employment growth in new businesses (Model III).

In contrast, the coefficients for the start-up rate of those new businesses that exited the market within the first 4 years (Models IV–VI) are considerably smaller than the estimated coefficients for all start-ups or for start-ups that survived 4 year or longer. When including both the start-up rate of businesses surviving at least 4 years as well as the start-up rate of businesses that exited within the first 4 years (Models VII–IX), we find significantly positive coefficients for the long-term survivors in all three models and negative coefficients for the effects of the short-term survivors that are statistically significant in two of the three models. The significantly negative coefficient for the short-term survivors on overall employment change (Model VII) suggests that the market turbulence caused by entries of relatively low quality, sometimes termed “churning” or as the “revolving door” phenomenon (Audretsch 1995), may have a deleterious effect. Thus our results indicate that an increasing number of short-term survivors is not beneficial for employment generation in new businesses. When considering both long- and short-term survivors, the coefficient of the short-term survivors on incumbent employment becomes insignificant (Model VIII). These results clearly indicate that the employment effects of new business formation are mainly driven by start-ups that have been able to survive for a certain period of time.

Chi2-testsFootnote 7 reveal that the differences between the estimated coefficients of the effects of new business formation on employment in incumbents and in new businesses are statistically significant (Table 4) for all start-ups and for the longer-term survivors, but not for short-term survivors. Also, the differences between the coefficients of the effects of short-term and long-term survivors on overall employment, incumbent employment, and employment in young businesses are statistically significant (Table 5).

6 Summary and conclusions

We investigated the impact of two types of new businesses on regional employment change; those start-ups that survive in the market for 4 years and more and those exiting the market within the first 3 years. We also showed that the positive correlation of new business formation and regional employment change is particularly caused by those start-ups strong enough to remain in the market for a certain period of time. This suggests that regions with relatively larger shares of low quality entries fail to translate entrepreneurial activity into employment growth. Particularly short-lived start-ups (“mayflies”) that exit the market shortly after entry have very little, if any impact on regional employment change. Moreover, our analyses reveal that the overall positive correlation between start-ups that have survived for a certain period of time and regional employment change does not derive solely from employment generated in the start-ups that have been set up in recent years, but that, instead, the larger part of this correlation originates from employment change in incumbent businesses that were already in existence at the time the newcomers entered the market. We argued that the interrelations between start-ups, their survival, and incumbent employment growth emphasizes the relevance of competitive pressure exerted by these entries and is, therefore, of an indirect nature.

These results have important implications for public policy as well as for further analyses of the effects of new business formation. Our analysis clearly suggests that it is not the mere number of start-ups, but their ability to compete successfully with incumbents and survive, that is important for their effect on regional development. Hence, a policy aimed at stimulating growth should put a focus on improving the quality of start-ups. Further research should investigate the determinants of start-up quality and how the quality of entries impacts their effects. Another avenue for further research is the role of market characteristics. As markets can vary considerably with regard to minimum efficient size, stage in the product life cycle, technological regime, etc., the effects of entry on competition may also vary with these characteristics of the market. Not much is known about such differences, yet.Footnote 8 Finally, future research should employ performance measures other than employment to assess the effect of entry on innovation, product variety, productivity, adjustment to environmental conditions, and market structure.Footnote 9 These issues are important starting points for improving our knowledge in this important field.

Notes

Indeed, entirely different results are found if, for example, the relationship between the level of start-ups and subsequent employment change is analyzed at the level of regions instead of at the level of industries (see Fritsch 1996). Therefore, geographical units of observation are much better suited for such an analysis than are industries.

In our data, new businesses are recorded at the time when they hire their first employee. Hence, a number of those businesses that are started without any employee but hire someone later on are recorded in that later year. Unfortunately, those start-ups that never have an employee, the solo-entrepreneurs, are not recorded in our data. Although it is known that this type of entrepreneurship has become more important in Germany during the 1990s (Boegenhold and Fachinger 2010), there is no information about solo-entrepreneurship available for smaller regional units such as planning regions. Although we cannot say anything in detail about the regional distribution of solo-entrepreneurs, we expect that the variables for regional industry structure, time dummies, and the regional fixed effects in our empirical model should prevent any significant distortion of the results caused by their omission. Given that these firms have no employee, we assume that their direct effects may be rather small if not negligible.

Analyzing regional differences of the direct employment effect of new business formation, Fritsch and Schindele (2011) take the number of employees in a start-up cohort after a certain period of time (2 or 10 years, respectively) over regional employment in the year before the new businesses have been set up as indicator for the direct effects. This measure is, however, not appropriate for a comparison with the indirect effects of new business formation because the effect of a certain start-up cohort on incumbent employment can hardly be empirically isolated for two reasons. First, the indirect effects take a period of about 10 years before they become fully evident so that the effects of different start-up cohorts overlap. Second, regional start-up rates tend to be rather constant over time so that the start-up rate for a certain year may not differ much from the average rate calculated for a longer period of time. Comparing the number of jobs that have been created in the start-up cohorts of the previous 10 years and that still exist in year \(t=\) 0 with change of incumbent employment is inappropriate for the same reason. The average employment share of start-up cohorts of the previous 10 years in year \(t=\) 0 is 23.1 percent (median: 22.5 percent).

This is also the main reason why firms that are older than three and a half years are classified as representing established business ownership in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM); see Reynolds et al. (2005).

All cross-model tests are based on results of seemingly unrelated estimations in order to account for cross-equation correlation.

Some studies separately analyze start-ups in manufacturing and those in the service sector (e.g., van Stel and Suddle 2008; Andersson and Noseleit 2011). Baptista and Preto (2011) perform analyses for knowledge-intensive service industries and compare the results with other sectors such as non-knowledge-intensive services.

The obvious reason why the vast majority of work on the effect of new business formation uses employment as an indicator of performance is data availability. Exemptions are Carree and Thurik (2008), who use GDP and labor productivity as dependent variables, and Thurik et al. (2008), who investigate the effect of self-employment and unemployment.

References

Aghion P, Blundell RW, Griffith R, Howitt P, Prantl S (2004) Entry and productivity growth: evidence from micro-level panel data. J Eur Econ Assoc 2:265–276

Aghion P, Blundell RW, Griffith R, Howitt P, Prantl S (2009) The effects of entry on incumbent innovation and productivity. Rev Econ Stat 91:20–32

Andersson M, Noseleit F (2011) Start-ups and employment growth—evidence from Sweden. Small Bus Econ 36:461–483

Audretsch DB (1995) Innovation and industry evolution. MIT Press, Cambridge

Audretsch DB, Fritsch M (2002) Growth regimes over time and space. Reg Stud 36:113–124

Baptista R, Preto MT (2011) New firm formation and employment growth: regional and business dynamics. Small Bus Econ 36:419–442

Birch DL (1981) Who creates jobs? Public Interest :3–14

Birch DL (1987) Job creation in America: how our smallest companies put the most people to work. Free Press, New York

Boegenhold D, Fachinger U (2010) Entrepreneurship and its regional development: do self-employment rations converge and does gender matter? In: Bonnet J , Garcia Perez De Lema D , Van Auken H (eds) The entrepreneurial society. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 54–76

Brüderl J, Schüssler R (1990) Organizational mortality: the liabilities of newness and adolescence. Admin Sci Q 35:530–547

Carree M, Thurik R (2008) The lag structure of the impact of business ownership on economic performance in OECD countries. Small Bus Econ 30:101–110

Caves RE (1998) Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. J Econ Lit 36:1947–1982

Davis SJ, Haltiwanger JC, Schuh S (1996) Small business and job creation: dissecting the myth and reassessing the facts. Small Bus Econ 8:297–315

Disney R, Haskell J, Heden Y (2003) Restructuring and productivity growth in UK manufacturing. Econ J 113:666–694

Falck O (2007) Mayflies and long-distance runners: the effects of new business formation on industry growth. Appl Econ Lett 14:1919–1922

Falck O (2009) New business formation, growth, and the industry lifecycle. In: Cantner U , Gaffard J-L , Nesta L (eds) Schumpeterian perspectives on innovation, competition and growth. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 299–311

Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung) (2003) Aktuelle Daten zur Entwicklung der Städte, Kreise und Gemeinden, vol 17. Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning, Bonn

Fritsch M (1996) Turbulence and growth in West-Germany: a comparison of evidence by regions and industries. Rev Ind Organ 11:231–251

Fritsch M (2013) New business formation and regional development—a survey and assessment of the evidence. In: Foundations and trends in entrepreneurship, vol 9

Fritsch M, Noseleit F (2012a) Investigating the anatomy of the employment effects of new business formation. Camb J Econ. doi:10.1093/cje/bes030

Fritsch M, Noseleit F (2012b) Indirect employment effects of new business formation across regions: the role of local market conditions. Papers in Regional Science

Fritsch M, Schindele Y (2011) The contribution of new businesses to regional employment—an empirical analysis. Econ Geogr 87:153–170

Fritsch M, Noseleit F, Schindele Y (2010) The direct and indirect effects of new businesses on regional employment: an empirical analysis. Int J Entrep Small Bus 10:49–64

Haltiwanger J, Jarmin RS, Miranda J (2010) Who creates jobs? Small vs. large vs. young. U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies. CES, Washington, DC, pp 10–17

Horrell M, Litan R (2010) After inception: how enduring is job creation by startups? Kauffman Foundation, Kansan City

Klepper S (1996) Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. Am Econ Rev 86:562–583

Kronthaler F (2005) Economic capability of East German regions: results of a cluster analysis. Reg Stud 39:739–750

Neumark D, Zhang J, Wall B (2006) Where the jobs are: business dynamics and employment growth. Acad Manag Perspect 20:79–94

Peneder M (2002) Industrial structure and aggregate growth. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 14:427–448

Redding SJ, Sturm DM (2008) The costs of remoteness: evidence from German division and reunification. Am Econ Rev 95:1766–1797

Reynolds PD et al (2005) Global entrepreneurship monitor: data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Bus Econ 24:205–231

Schindele Y, Weyh A (2011) The Direct employment effects of new businesses in Germany revisited—an empirical investigation for 1976–2004. Small Bus Econ 36:353–363

Spengler A (2008) The establishment history panel. Schmollers Jahrbuch/J Appl Soc Sci Stud 128:501–509

Spletzer JR (2000) The contribution of establishment births and deaths to employment growth. J Bus Econ Stat 18:113–126

Stangler D, Kedrosky P (2010) Neutralism and entrepreneurship: the structural dynamics of startups, young firms and job creation. Kauffman Foundation, Kansas City

Südekum J (2008) Convergence of the skill composition across German regions. Reg Sci Urban Econ 38:148–159

Thurik RA, Carree MA, van Stel A, Audretsch DB (2008) Does self-employment reduce unemployment? J Bus Venturing 23:673–686

van Stel A, Suddle K (2008) The impact of new firm formation on regional development in the Netherlands. Small Bus Econ 30:31–47

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fritsch, M., Noseleit, F. Start-ups, long- and short-term survivors, and their contribution to employment growth. J Evol Econ 23, 719–733 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-012-0301-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-012-0301-5