Abstract

In recent years, scholars have started to draw on upper echelons theory to analyze the relationship between the characteristics of top managers and management accounting and control systems. This short survey paper aims to give an overview of upper echelons theory and its current applications to management accounting and control research. The paper shows that existing research consistently finds that younger and shorter-tenured CFOs and top managers with business-related backgrounds are associated with more innovative and/or sophisticated management accounting and control systems. In contrast, the (sparse) extant results on CEO characteristics and on characteristics of top management teams are somewhat contradictory. The paper concludes with an outlook on fruitful future research avenues, which include the analysis of additional management accounting and control systems and additional upper echelon characteristics, moderators such as managerial discretion and executive job demands, and the combined effect of upper echelons and management accounting and control systems on organizational performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last decades, academic interest in the top managers of business organizations has greatly increased. A key theory that has accompanied and most likely fostered this upsurge in interest in top managers is upper echelons theory (Carpenter et al. 2004; Finkelstein et al. 2009; Nielsen 2010). The fundamental idea of this theory is captured well by the subheading of Hambrick and Mason’s (1984) seminal paper on the upper echelons perspective: the organization is a reflection of its top managers (the so-called “upper echelons”). The theory acknowledges that individual top managers heavily influence organizational outcomes by the choices they make, which are—in turn—affected by the managers’ characteristics. Hambrick and Mason (1984) further postulated that the characteristics of the upper echelons and their strategic choices help to explain an organization’s performance.

Management accounting and control systems can be seen as an organizational outcome or as an aspect of organizational structure (Chenhall 2003; Strauß and Zecher 2013) and—following upper echelons theory—can thus be expected to also be influenced by top-manager characteristics. Hambrick and Mason (1984, p. 199) identified “administrative complexity” as one important dimension of strategic choices that is influenced by upper echelons, and mentioned “thoroughness of formal planning systems, complexity of structures and coordination devices, budgeting detail and thoroughness, and complexity of incentive compensation schemes” as ingredients of “administrative complexity”, all of which can be classified as management accounting or control practices (Chenhall 2003; Luft and Shields 2003; Guenther 2013). In line with this view, in their influential paper on management control systems as a package, Malmi and Brown (2008, p. 294) acknowledged that organizational controls are “something that managers can change, as opposed to something that is imposed on them”. Consequently, a substantial influence of top managers and their characteristics on the design of management accounting and control systems can be assumed.

The present short survey paper aims to summarize extant findings on this link and to present opportunities for further research on the topic. Overall, the paper shows that including the individual influence of top managers on the design of management accounting and control systems can help to create a more comprehensive picture of the antecedents of such systems than studying environmental and firm-level factors alone would allow. Thus, complementing often studied environmental and firm-level contingency factors such as environmental uncertainty, industry characteristics, firm strategy, and firm size (Chenhall 2003; Luft and Shields 2003) with upper echelon characteristics can be expected to help increase the explanatory power of management accounting and control research (similar to Ge et al. 2011, who identified—in addition to firm-specific effects—distinct CFO-specific effects on financial accounting choices). Amongst other results, the paper shows that, for CFOs, research is conclusive that younger age and shorter tenure are associated with more innovative and sophisticated management accounting and control systems. While the same is found true for the business-related backgrounds of top managers, research on CEO characteristics yields contradictory results.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the main tenets of upper echelons theory are presented. Section 3 describes the methods applied to identify relevant prior research, and Sect. 4 summarizes the findings on applications of upper echelons theory in the management accounting and control literature. Section 5 delivers an outlook on future research opportunities, and Sect. 6 provides a brief conclusion.

2 Upper echelons theory

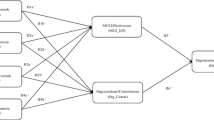

Hambrick and Mason (1984) derived the idea that managerial characteristics can be used to (partially) predict organizational outcomes (in the case of this paper: management accounting and control systems) based on the notion that the choices of top managers are influenced by their cognitive base and their values. Since such psychological constructs are difficult to observe, they suggested that the demographic characteristics of top managers can be used as proxies for their cognitive base and values. This is why the relationship between observable managerial characteristics and strategic choices (often also termed “organizational outcomes”) lies at the core of the theory. Typical characteristics and areas of strategic choices can be seen in Fig. 1, which shows a simplified conceptual model of upper echelons theory.Footnote 1 Hambrick and Mason (1984) added that both the characteristics and strategic choices of upper echelons may be influenced by the situational characteristics of the organization, such as external environment or firm characteristics, which are thus antecedents to managerial characteristics and/or organizational outcomes (Carpenter et al. 2004; Nielsen 2010). According to upper echelons theory, managerial characteristics also affect organizational performance, either directly or mediated by organizational outcomes (Hambrick and Mason 1984).

Hambrick (2007) later suggested two moderators of the relationship between managerial characteristics and organizational outcomes—namely managerial discretion and executive job demands—to complement the traditional upper echelon model as proposed in Hambrick and Mason (1984). Managerial discretion refers to the latitude of action top managers enjoy in making strategic choices (Hambrick and Finkelstein 1987; Carpenter et al. 2004; Crossland and Hambrick 2011). Thus, Hambrick (2007) proposed that, if managerial discretion is high, managerial characteristics will be better predictors of organizational outcomes than if managerial discretion is low. The second moderator—executive job demands—refers to the levels of challenge top managers face (Hambrick et al. 2005). Hambrick (2007) postulated that top managers who face a high level of challenges will have less time to contemplate decisions and therefore take mental shortcuts and rely more on their personal backgrounds. Thus, he predicts that the relationship between managerial characteristics and organizational outcomes will be stronger when the level of managerial challenges is high. In situations where managers face a lower level of challenges, in contrast, their decision-making will be more thorough and rely less on their personal characteristics. Hence, the link between upper echelon characteristics and organizational outcomes should be weaker in such situations (Hambrick 2007).

3 Identification of relevant papers

To identify empirical findings on the application of upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research, a two-step approach was followed. The first step consisted of a keyword search for academic journal articles in the electronic databases Scopus, EBSCO Business Source Premier, ProQuest ABI/INFORM and ISI Web of Knowledge.Footnote 2 The second step consisted of scanning the references of the identified articles and searching for articles citing the previously identified articles in order to find additional articles which relate to the topic of this paper. The entire procedure resulted in a total of twelve articles, an overview of which is given in Table 1.

All twelve articles included in this review adopted a quantitative research approach. While four papers investigated the effect of top management team characteristics (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2006, 2007b; Kyj and Parker 2008; Speckbacher and Wentges 2012), four papers analyzed the effect of individual characteristics of top managers (CEOs, CFOs) on management accounting and control (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2007a; Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009; Pavlatos 2012; Abernethy et al. 2010), and one paper additionally investigated the characteristics of two upper echelons (CEO and CFO) (Burkert and Lueg 2013). The paper by Lee et al. (2013) included both findings on characteristics of the entire top management team and findings on characteristics of the chief information officer (CIO). Two papers investigating the effect of managers’ knowledge and leadership style on management accounting and control systems (Hartmann et al. 2010; Elbashir et al. 2011) not only included top managers in their analysis, but also middle managers. Although middle managers may not be regarded as upper echelons in terms of Hambrick and Mason (1984), papers reporting on middle managers’ leadership style were also included in the present review because their findings on the general leadership style of managers may also be applicable to top managers. Interestingly, four out of the five papers co-authored by (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2006, 2007a, b; Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009) seem to rely on the same sample of Spanish hospitals. The two papers co-authored by Elbashir and Sutton (Elbashir et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013) also seem to be based on the same survey of Australian organizations using business intelligence software.

4 Extant empirical findings

To create an overview of the extent to which upper echelons theory is applied in management accounting and control research, Malmi and Brown’s (2008) typology of management control systemsFootnote 3 was used to classify the relationships between top management characteristics and management accounting and control systems studied in published literature. Table 2 visualizes these relationships.

4.1 CEO characteristics

Although management accounting and control systems often fall into the CFO’s area of responsibility, CEOs will also likely exert decisive influence on the design of such systems. This is to be expected, as control systems, which are geared towards directing management and employee behavior (Malmi and Brown 2008), are used by (and thus of interest to) not only CFOs, but also CEOs, who are at the top of the corporate hierarchy and who may wish to ensure that subordinates act in their interest. Thus, CEOs (and their characteristics) can be expected to impact on systems designed to support this endeavor (i.e., management accounting and control systems).

The three studies on the relationship between CEO characteristics and management accounting and control systems included in this review deliver somewhat mixed results. For a sample of Spanish hospitals, Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2007a) found that CEO backgrounds (in terms of education and experience) are significantly associated with the design of management control systems. CEOs with a predominantly administrative (business-related) background are positively associated with higher use of financial information. Further, the presence of such CEOs is associated with a more diagnostic than interactive use of management control systems and a greater emphasis on performance evaluation than resource allocation. For hospitals with clinical-background (non-business-related) CEOs, Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2007a) found that such CEOs are related to higher use of non-financial information and more interactive than diagnostic use of management control systems. In contrast, Burkert and Lueg (2013) did not find a significant impact of CEO characteristics on the sophistication of value-based management systems in German listed firms.

Besides demographic CEO characteristics, Abernethy et al. (2010) presented evidence that a CEO’s leadership style also impacts the design and usage of management accounting and control systems. They reported that both CEOs with a considerate leadership style (creating a work atmosphere with subordinates that is characterized by trust, support, appreciation, and respect, see Judge et al. (2004)) and those with a leadership style focused on initiating structure (clearly defining role, patterns of communication, and oriented towards goal attainment, see Judge et al. (2004)Footnote 4) lead to more interactive communication in using planning and control systems.Footnote 5 Moreover, Abernethy et al. (2010) found that CEOs who focus their leadership style on initiating structure show higher usage of performance measurement systems when deciding on their subordinates’ promotion and compensation. However, they did not find a significant relationship between a CEO’s considerate leadership style and reward and compensation systems and between both types of leadership style and delegating decision-making power from the CEO to subordinates.Footnote 6

4.2 CFO characteristics

For the relationship between CFO characteristics and management accounting and control systems, empirical results are more consistent than for CEO characteristics. Naranjo-Gil et al. (2009) showed that younger and shorter-tenured CFOs as well as CFOs with a business education (in contrast to an operations-oriented education, for instance, in medicine or nursing) are associated with the use of innovative management accounting instruments such as the balanced scorecard (a hybrid measurement system according to Malmi and Brown’s (2008) typology), activity-based costing (a financial measurement system), and benchmarking (classified in Table 2 as a non-financial measurement system). However, Naranjo-Gil et al. (2009) included all three management accounting innovations in one continuous scale to measure the innovativeness of systems, thus precluding insights into how CFO characteristics influence individual systems, which are—as defined by Malmi and Brown (2008)—very different types of controls. In line with the findings by Naranjo-Gil et al. (2009), Pavlatos (2012) showed for a sample of Greek hotels that firms with younger CFOs and CFOs with a business-oriented educational background exhibit more comprehensive use of cost-management systems. However, in contrast to the findings by Naranjo-Gil et al. (2009), Pavlatos’ (2012) analysis of CFO tenure does not yield significant results.

Reinforcing the importance of CFO characteristics for management accounting and control systems, Burkert and Lueg (2013) presented evidence that shorter-tenured CFOs and CFOs with a business education (in contrast to CFOs with a non-business-related education) are associated with more sophisticated value-based management systems (classified in Table 2 as financial measurement systems). Furthermore, they showed that the effect of a CFO’s educational background seems to dominate the effect of length of CFO tenure. Their results indicate that, regardless of (short) tenure, CFOs with a business-related education are associated with a higher sophistication of value-based management systems.

4.3 CIO characteristics

Currently, the only paper analyzing the relationship between CIO characteristics and management accounting and control systems is that published by Lee et al. (2013). They found that the CIO’s strategic business and IT knowledge affects the extent to which the top management team believes that business intelligence software (according to Lee et al. (2013), a sort of management control system innovation) can create benefits for their organization.Footnote 7 Lee et al. (2013) found that the management team’s belief in business intelligence systems in turn positively affects top managers’ participation in using business intelligence systems. They interpreted these findings as a sign of knowledgeable CIOs and of their collaboration with the top management team playing an important role in making the top management team aware of the value of management control system innovations such as the usage of business intelligence software.

4.4 Characteristics of (top) management teams

Finally, seven studies investigated the relationship between characteristics of (top) management teams and management accounting and control systems. Although not explicitly referring to upper echelons theory, Speckbacher and Wentges (2012) analyzed a characteristic of top managers which is very common among smaller firms, namely top managers being members of the family which owns the respective firm. They presented evidence that—compared to firms which also include non-family members in their top management team—firms in which all top management team members are part of the controlling family show lower use of (i) multi-perspective performance measures for strategic target setting (hybrid measurement systems according to Malmi and Brown (2008)), (ii) incentive contracts for middle management (part of reward and compensation controls according to Malmi and Brown (2008)) and (iii) balanced scorecard-type performance measurement systems (also hybrid measurement systems). As potential reasons for these findings, Speckbacher and Wentges (2012) noted that—in comparison to non-family managers—family members can rely more on social networks, tacit knowledge, and generally more informal modes of management control. Non-family managers, in contrast, frequently lack these resources and thus need to introduce more formal control systems. However, Speckbacher and Wentges (2012) also showed that their findings are more pronounced in small firms and less pronounced in large firms.

The study by Hartmann et al. (2010) on Dutch middle managers from various industries also analyzed the impact of managers on two aspects of reward and compensation controls. They found that a leadership style geared towards initiating structure results in greater reliance on objective and subjective performance measures when determining subordinates’ monetary and non-monetary rewards. In contrast, they did not find this relationship for a considerate leadership style. However, Hartmann et al. (2010) presented evidence that a clearly considerate leadership style—unlike a structuring leadership style—positively influences the subordinates’ perceived clarity of their individual goals (classified in Table 2 as part of the governance structure and thus administrative controls) and level of fairness when their performance is evaluated (classified in Table 2 as part of reward and compensation controls). Thus, as shown in Table 2, Hartmann et al.’s (2010) findings can be interpreted as presenting evidence that the considerate leadership style shows a significant relationship with one aspect of reward and compensation controls (goal clarity), while no significant relationship could be found with another aspect of reward and compensation controls (reliance on performance measures when determining rewards). For a structuring leadership style, they presented exactly opposite findings.

Kyj and Parker (2008) showed that considerate superiors encourage their subordinates to participate actively in the budgeting process, thus creating a significant relationship between considerate leadership style and one aspect of budgetary control (as shown in Table 2). Further, they showed that encouragement by superior managers also results in greater participation of subordinates in the budgeting process.

In another study using their sample of Spanish hospitals, Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2006) found that top management teams with more members with administrative backgrounds (in contrast to professional, i.e., clinical, backgrounds) make more diagnostic use of management accounting systems (in contrast to interactive use) and rely more on financial than on non-financial information. Moreover, they showed that, although top management teams with administrative backgrounds exhibit different use of management accounting systems compared to teams with clinical backgrounds, both types of top management teams can result in the organization pursuing similar strategies (cost strategies or flexibility strategies in the case of Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2006)). In an analysis of top management team heterogeneity (in terms of age, length of tenure, experience, and education), Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2007b) presented evidence that greater heterogeneity is positively associated with interactive use of management accounting systems, but they did not find a relationship with the scope of management accounting systems.Footnote 8 However, they showed that the effect of top management team heterogeneity on changes in the organization’s basic strategy is mediated by interactive use and the scope of management accounting systems.

Finally, the study by Elbashir et al. (2011) presented evidence that the top management team’s absorptive capacity (i.e., the capacity to create new knowledge) positively affects the absorptive capacity of operational-level managers, which in turn positively influences the respective firm’s IT infrastructure sophistication and usage of business intelligence software. Elbashir et al. (2011) interpreted these findings as evidence that the top management team’s absorptive capacity serves as an aspect of cultural controls as defined by Malmi and Brown (2008) (and displayed in Table 2), which encourages subordinates to also create absorptive capacity on the operational level. Elbashir et al. (2011) further showed that the top management team’s absorptive capacity influences neither IT infrastructure sophistication nor business intelligence usage directly, but only indirectly via the absorptive capacity of operational-level managers.

5 Outlook

Table 2 reveals that empirical studies on upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research have analyzed the relationship of top management characteristics with a variety of cybernetic controls such as budgeting systems (Kyj and Parker 2008; Abernethy et al. 2010), financial measurement systems (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2006, 2007a; Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009; Burkert and Lueg 2013; Pavlatos 2012), non-financial measurement systems (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2006, 2007a; Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009), hybrid measurement systems (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2007b; Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009; Speckbacher and Wentges 2012), and how top managers use these cybernetic controls (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2006, 2007a, b). Further, the analysis of the impact of upper echelon characteristics on reward and control systems has also received considerable attention in management accounting and control research (Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010; Speckbacher and Wentges 2012). Two studies each analyzed the influence of managerial characteristics on administrative controls (Abernethy et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2010) and on cultural controls (Elbashir et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013).

For CFO characteristics, the findings are broadly consistent and reveal that younger and shorter-tenured CFOs are associated with increased use or higher sophistication of the aforementioned systems. The findings consistently point to the notion that top managers with a background in business (in terms of education and experience) use these systems to a higher degree and in a more diagnostic way and focus more on financial than non-financial controls. However, for CEO characteristics, the (sparse) empirical results are somewhat contradictory, as shown above. The results concerning both the CEO’s and other managers’ leadership styles suggest that a considerate leadership style results in greater encouragement for subordinates to participate in the budgeting process and more interactive use of budgets. However, the results concerning the effect of leadership styles on reward and compensation controls as well as administrative controls do not yet form a clear and consistent picture. The papers by Elbashir et al. (2011) and Lee et al. (2013) on cultural controls point to the notion that both the top management team’s and the CIO’s knowledge and absorptive capacity may enable the rest of the organization to adopt more innovative management accounting and control systems.

5.1 Research on (further) management accounting and control systems

As Table 2 also reveals, many blanks remain in the analysis of the influence of upper echelon characteristics on management accounting and control systems. It seems surprising that the management accounting and control literature remains silent on how top management characteristics affect the usage of specific planning systems as organizational controls. We only have some incidental insights from the strategic management literature that higher top management team diversity (in terms of preferences and beliefs) tends to inhibit comprehensiveness and extensiveness of long-range planning (Miller et al. 1998). Given the current debate that CFOs should develop (or have already developed) into important players in the strategic management process (e.g., Zorn 2004; Baxter and Chua 2008; Hiebl 2013), additional research could shed light on how CFO characteristics are associated with the adoption of strategic planning instruments and—similar to the approach of Burkert and Lueg (2013)—whether these instruments depend more on the CEO (characteristics) or on the CFO (characteristics). Such research would also be valuable for practice, as it could show corporate owners and CEOs how strategic management processes could benefit from hiring a certain type of CFO.

Speckbacher and Wentges’ (2012) findings indicate that family-managed firms, which constitute a large proportion of all firms in industrialized countries (IFERA 2003), may rely more on informal controls than firms managed by external managers. Such informal controls could be clan controls, value controls, or symbol-based controls, as shown by Malmi and Brown (2008). Considering their dual role as managers and owners, family managers (and their characteristics) can be expected to exert especially high influence on the design of management accounting and control systems. Given the vast economic importance of family firms, a deeper understanding of how such cultural controls are shaped by family managers’ characteristics seems valuable. In this connection it might also be interesting (and relevant for practice) to investigate under which leadership such cultural and more informal controls are beneficial or detrimental to firm performance because it seems possible that cultural controls are only effective alternatives for more formal control systems (such as cybernetic controls) when family members (and thus owners) are part of the management team.

5.2 Research on (further) upper echelon characteristics

Besides the study of additional management accounting and control systems analysis of hitherto contradictory results on certain upper echelon characteristics and of additional upper echelon characteristics and moderating variables as suggested by Hambrick (2007) seems worthwhile. For example, it would be valuable to clarify the effects of CEO education and CFO tenure on financial measurement systems. While Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2007a) found a significant impact of CEO education on financial measurement systems, Burkert and Lueg (2013) did not. These contradictory results could potentially be traced back to the organizations under investigation. While Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2007a) studied only CEOs of public non-profit hospitals, Burkert and Lueg (2013) studied both CEOs and CFOs of large listed profit-oriented corporations. The contradiction may therefore be due to the different industries studied (healthcare in the case of Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann (2007a) versus various industries in the case of Burkert and Lueg (2013)), the different status in terms of profit orientation of the underlying organizations, and/or the simultaneous analysis of CEOs and CFOs (the CFO effect may outshine the CEO effect). Similarly, it would be interesting to clarify for additional industries, firm sizes, and countries whether the finding that CFOs with shorter tenure are associated with more sophisticated financial measurement systems applies (as suggested by Naranjo-Gil et al. (2009) and Burkert and Lueg (2013)) or not (as the findings by Pavlatos (2012) suggest).

Moreover, it would also be rewarding to reconsider some basic elements of upper echelons theory which have not yet been analyzed in management accounting and control research. For instance, studies have analyzed only a small set of managerial characteristics as predictors of the design of management accounting and control systems. Besides age, length of tenure, education, and experience of top managers, homogeneity of top management teams (Naranjo-Gil and Hartmann 2006, 2007a, b; Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009; Pavlatos 2012; Burkert and Lueg 2013), leadership style (Kyj and Parker 2008; Hartmann et al. 2010; Abernethy et al. 2010), absorptive capacity (Elbashir et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2013), and ownership status of top managers (Speckbacher and Wentges 2012), seminal papers on upper echelons theory and related works suggest a variety of further characteristics that influence organizational outcomes significantly. Among these, recruitment, socioeconomic status, personal financial situation, and gender of the top managers come to mind.

Hambrick and Mason (1984) suggested that externally hired top managers make more changes to an organization than those hired internally. Findings from case study research (Baxter and Chua 2008; Goretzki et al. 2013; Goretzki 2013) indicate that this may also be true for newly hired CFOs (or potentially also CEOs) who enter an organization from the outside and subsequently make substantial changes to management accounting and control systems. Related studies (e.g., Geiger and North 2006; Li et al. 2010) show that substantial changes to finance and financial accounting practices can be observed in firms with newly hired CFOs. Studying the effect of externally recruited CFOs (or CEOs) on management accounting and control systems would also help practitioners to better understand and foresee the aftermath of CFO changes. When studying the effect of such CFOs on management accounting and control change, it would be valuable to control for simultaneous changes in the CEO position, as previous findings suggest that the career fates of CFOs and CEOs are often closely linked (Mian 2001; Arthaud-Day et al. 2006; Zander et al. 2009; Hilger et al. 2013).

Hambrick and Mason (1984) further proposed that the socioeconomic status and financial position of top managers may affect their corporate actions. In this context, empirical findings show that higher socioeconomic status and personal wealth of CEOs is associated with less risk-seeking actions in corporate finance decisions (Roussanov 2010; Lucey et al. 2013). Considering these results, it may be conjectured that top managers with higher socioeconomic status and personal wealth also display a lower preference for risky choices when it comes to adopting or developing (innovative) management accounting and control systems (which is similar to Hambrick and Masons’s (1984) argument that older and longer-tenured managers are more risk-averse and less open for innovations to organizational structure). Another top manager characteristic associated with risk-seeking or risk-avoiding behavior is gender. In this regard, Huang and Kisgen (2013) have recently shown that male CEOs and CFOs are more risk-seeking in terms of issuing debt and acquisitions than their female counterparts. Thus, it may also be rewarding to test the relationship between gender of the top manager and adoption of (innovative) management accounting and control systems.

When analyzing the above-presented additional managerial characteristics and/or organizational outcomes, future studies would also benefit from including important moderators inherent in upper echelons theory, as displayed in Sect. 2, which have not yet been covered in studies applying upper echelons theory to management accounting and control research. In this vein, very challenging executive job demands and high managerial discretion can be expected to lead to managerial characteristics that are better predictors of the design of management accounting and control systems. For financial accounting choices, Ge et al. (2011) have already documented that CFO discretion and CFO job demands indeed moderate the relationship between CFO characteristics and reporting choices. Including managerial discretion and job demands would also be important in studies on the effect of CFO characteristics on management accounting and control systems because the position “CFO”, for instance, as defined by Mian (2001)Footnote 9, does not include a clear statement on the hierarchical level of the CFO (whereas CEOs can be expected to be on the first level). Some empirical CFO studies do not disclose the hierarchical level of the CFOs under investigation (e.g., Geiger and North 2006; Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009; Pavlatos 2012; Burkert and Lueg 2013), while others also deliberately include CFOs from the second, third, or lower levels (Gallo and Vilaseca 1998; Gallo et al. 2004; Dunford et al. 2010). However, it is to be expected that CFOs from the first hierarchical level have higher levels of managerial discretion than CFOs from lower levels. Similarly, CFOs from the first hierarchical level may be under higher pressure from capital markets and shareholders and may therefore experience more challenging job situations than CFOs from lower hierarchical ranks. Thus, in order to create a more comprehensive picture of the effect of CFO characteristics on management accounting and control systems, integrating managerial discretion, executive job demands, and the hierarchical position of the CFO seems valuable. Moreover, when integrating managerial discretion in upper echelon studies on management accounting and control systems, future research should also take into account that managerial discretion may vary depending on industry or national culture (Crossland and Hambrick 2011).

5.3 Research on organizational performance

Finally, future studies may also benefit from analyzing the whole chain of relationships as proposed in upper echelons theory from situational factors to upper echelon characteristics, organizational outcomes, and performance. Although the studies analyzed in this paper included performance metrics as control variables (Burkert and Lueg 2013) or antecedents of the use of management accounting systems (Naranjo-Gil et al. 2009), they did not analyze performance as a result of upper echelon characteristics and/or organizational outcomes. However, it could well be theorized that certain managerial characteristics better suit certain management accounting and control systems than others. A good fit between these two constructs may in turn enable more effective steering of the firm and thus better performance. Put differently, upper echelon characteristics may interact with management accounting and control choices to explain organizational performance.

For instance, as indicated above, it might be that only family managers can handle informal or cultural controls effectively to the benefit of the firm, while other managers (non-family managers) could never achieve comparable performance. Similarly, managers with certain characteristics (e.g., with considerate leadership style) might make better choices and thus foster performance when using their management accounting and control systems interactively, while other managers (e.g., with structured leadership style) achieve this when using these systems in a more diagnostic way. Such integrative studies would therefore be valuable in judging which upper echelon characteristics lead (in which situations) to management accounting and control systems associated with high performance and thus might be especially helpful in creating suggestions for practice.

6 Conclusion

This short survey paper sought to give an overview of upper echelons theory and its application in management accounting and control research. Although research has, for instance, shown that younger and shorter-tenured CFOs and, in general, top managers with business-related backgrounds are associated with more innovative and/or sophisticated management accounting and control systems, a wide range of promising avenues for future research remains open. Valuable contributions could be created by addressing the effect of additional management accounting and control systems and upper echelon characteristics, and by investigating moderators such as managerial job demands and managerial discretion and relationships with organizational performance. Such research will not only increase our general understanding of the relationship between top management characteristics and management accounting and control systems, but might also result in valuable advice for practitioners seeking to appoint suitable candidates to managerial positions and/or aiming to introduce more sophisticated or innovative management accounting and control systems.

Notes

Besides typical demographic upper echelon characteristics such as age, career experience, and education, Fig. 1 also contains leadership style, since Waldman et al. (2004) have shown that leadership style—as another upper echelon characteristic—significantly contributes to the ability of upper echelon models to predict organizational performance.

To be considered for this review, articles were required to feature the following keywords in their title, abstract and/or author-generated article keywords. The search phrase used was (“upper echelon*” OR “CFO characteristic*” OR “chief financial officer characteristic*” OR “CEO characteristic*” OR “chief executive officer characteristic*” OR “CEO demographic*” OR “CFO demographic*” OR “chief executive officer demographic*” OR “chief financial officer demographic*” OR “top management team*” OR “leadership style*”) AND (“management account*” OR “management control*”). Note that asterisks in the search phrase allowed for different keyword endings; for instance, “management account*” captured both “management accounting” and “management accountant”. The search results reflect the articles available in print or online ahead of print as per October 31, 2013.

Although Malmi and Brown (2008, p. 290) clearly distinguish between the purpose of management control systems (“put in place in order to direct employee behavior”) and management accounting systems (“designed to support decision-making at any organizational level, but leave the use of those systems unmonitored”), they acknowledge that the same instruments (such as planning or costing systems) can be used for management control and management accounting at the same time. Thus, their typology is used to map the results in this review paper, as their framework presents a comprehensive typology of management control systems and the present paper aims to summarize relationships between upper echelon characteristics and management accounting and control systems without a strict focus on their underlying purpose.

Note that considerate and structuring leadership styles are not opposites. Managers can score high (or low) on both types of leadership styles at the same time (Abernethy et al. 2010).

Mian (2001) defines a CFO as the position responsible for overseeing the firm’s accounting function, for the preparation of financial results, for the firm’s treasury side of the business and consequently for raising capital.

References

Abernethy, M. A., Bouwens, J., & van Lent, L. (2010). Leadership and control system design. Management Accounting Research, 21(1), 2–16.

Arthaud-Day, M. L., Certo, S. T., Dalton, C., & Dalton, D. R. (2006). A changing of the guard: executive and director turnover following corporate financial restatements. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1119–1136.

Baxter, J., & Chua, W. F. (2008). Be(com)ing the chief financial officer of an organisation: Experimenting with Bourdieu’s practice theory. Management Accounting Research, 19(3), 212–230.

Burkert, M., & Lueg, R. (2013). Differences in the sophistication of value-based management: The role of top executives. Management Accounting Research, 24(1), 3–22.

Carpenter, M. A., Geletkanycz, M. A., & Sanders, W. G. (2004). Upper echelons research revisited: Antecedents, elements, and consequences of top management team composition. Journal of Management, 30(6), 749–778.

Chenhall, R. H. (2003). Management control systems design within its organizational context: Findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2–3), 127–168.

Crossland, C., & Hambrick, D. C. (2011). Differences in managerial discretion across countries: How nation-level institutions affect the degree to which CEOs matter. Strategic Management Journal, 32(8), 797–819.

Dunford, B. B., Boswell, W. R., & Boudreau, J. W. (2010). When do high-level managers believe they can influence the stock price? Antecedents of stock price expectancy cognitions. Human Resource Management, 49(1), 23–43.

Elbashir, M. Z., Collier, P. A., & Sutton, S. G. (2011). The role of organizational absorptive capacity in strategic use of business intelligence to support integrated management control systems. The Accounting Review, 86(1), 155–184.

Finkelstein, S., Hambrick, D. C., & Cannella, A. A. (2009). Strategic leadership: Theory and research on executives, top management teams, and boards. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gallo, M. A., Tàpies, J., & Cappuyns, K. (2004). Comparison of family and nonfamily business: Financial logic and personal preferences. Family Business Review, 17(4), 303–318.

Gallo, M. A., & Vilaseca, A. (1998). A financial perspective on structure, conduct and performance in the family firm: An empirical study. Family Business Review, 11(1), 35–47.

Ge, W., Matsumoto, D., & Zhang, J. L. (2011). Do CFOs have style? An empirical investigation of the effect of individual CFOs on accounting practices. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(4), 1141–1179.

Geiger, M. A., & North, D. S. (2006). Does hiring a new CFO change things? An investigation of changes in discretionary accruals. The Accounting Review, 81(4), 781–809.

Goretzki, L. (2013). Management accounting and the construction of the legitimate manager. Journal of Management Control, 23(4), 319–344.

Goretzki, L., Strauss, E., & Weber, J. (2013). An institutional perspective on the changes in management accountants’ professional role. Management Accounting Research, 24(1), 41–63.

Guenther, T. W. (2013). Conceptualisations of ‘controlling’ in German-speaking countries: Analysis and comparison with Anglo-American management control frameworks. Journal of Management Control, 23(4), 269–290.

Hambrick, D. C. (2007). Upper echelons theory: An update. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 334–343.

Hambrick, D. C., & Finkelstein, S. (1987). Managerial discretion: A bridge between polar views of organizational outcomes. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 369–406.

Hambrick, D. C., Finkelstein, S., & Mooney, A. C. (2005). Executive job demands: New insights for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 472–491.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206.

Hartmann, F., Naranjo-Gil, D., & Perego, P. (2010). The effects of leadership styles and use of performance measures on managerial work-related attitudes. European Accounting Review, 19(2), 275–310.

Hiebl, M. R. W. (2013). Bean counter or strategist? Differences in the role of the CFO in family and non-family businesses. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 4(2), 147–161.

Hilger, S., Richter, A., & Schäffer, U. (2013). Hanging together, together hung? Career implications of interpersonal ties between CEOs and top managers. BuR-Business Research, 6(1), 8–32.

Huang, J., & Kisgen, D. J. (2013). Gender and corporate finance: Are male executives overconfident relative to female executives? Journal of Financial Economics, 108(3), 822–839.

IFERA. (2003). Family businesses dominate: Families are the key players around the world, but prefer the backstage positions. Family Business Review, 16(4), 235–239.

Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., & Ilies, R. (2004). The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 36–51.

Kyj, L., & Parker, R. J. (2008). Antecedents of budget participation: Leadership style, information asymmetry, and evaluative use of budget. Abacus, 44(4), 423–442.

Lee, J., Elbashir, M. Z., Mahama, H., & Sutton, S. G. (2013). Enablers of top management team support for integrated management control systems innovations. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems. doi:10.1016/j.accinf.2013.07.001.

Li, C., Sun, L., & Ettredge, M. (2010). Financial executive qualifications, financial executive turnover, and adverse SOX 404 opinions. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(1), 93–110.

Lucey, B. M., Plaksina, Y., & Dowling, M. (2013). CEO social status and acquisitiveness. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 5(2), 161–177.

Luft, J., & Shields, M. D. (2003). Mapping management accounting: Graphics and guidelines for theory-consistent empirical research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2–3), 169–249.

Malmi, T., & Brown, D. A. (2008). Management control systems as a package: Opportunities, challenges and research directions. Management Accounting Research, 19(4), 287–300.

Mian, S. (2001). On the choice and replacement of chief financial officers. Journal of Financial Economics, 60(1), 143–175.

Miller, C. C., Burke, L. M., & Glick, W. H. (1998). Cognitive diversity among upper-echelon executives: implications for strategic decision processes. Strategic Management Journal, 19(1), 39–58.

Naranjo-Gil, D., & Hartmann, F. (2006). How top management teams use management accounting systems to implement strategy. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 18, 21–53.

Naranjo-Gil, D., & Hartmann, F. (2007a). How CEOs use management information systems for strategy implementation in hospitals. Health Policy, 81(1), 29–41.

Naranjo-Gil, D., & Hartmann, F. (2007b). Management accounting systems, top management team heterogeneity and strategic change. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7–8), 735–756.

Naranjo-Gil, D., Maas, V. S., & Hartmann, F. G. H. (2009). How CFOs determine management accounting innovation: An examination of direct and indirect effects. European Accounting Review, 18(4), 667–695.

Nielsen, S. (2010). Top management team diversity: A review of theories and methodologies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(3), 301–316.

Pavlatos, O. (2012). The impact of CFOs’ characteristics and information technology on cost management systems. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 13(3), 242–254.

Roussanov, N. (2010). Diversification and its discontents: Idiosyncratic and entrepreneurial risk in the quest for social status. The Journal of Finance, 65(5), 1755–1788.

Speckbacher, G., & Wentges, P. (2012). The impact of family control on the use of performance measures in strategic target setting and incentive compensation: A research note. Management Accounting Research, 23(1), 34–46.

Strauß, E., & Zecher, C. (2013). Management control systems: A review. Journal of Management Control, 23(4), 233–268.

Waldman, D. A., Javidan, M., & Varella, P. (2004). Charismatic leadership at the strategic level: A new application of upper echelons theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(3), 355–380.

Zander, K., Büttner, V., Hadem, M., Richter, A., & Schäffer, U. (2009). Unternehmenserfolg, Wechsel im Vorstandsvorsitz und Disziplinierung von Finanzvorständen. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, 79(12), 1343–1386.

Zorn, D. M. (2004). Here a chief, there a chief: The rise of the CFO in the American firm. American Sociological Review, 69(3), 345–364.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous reviewers for their most helpful comments and Ingrid Abfalter for her outstanding assistance in language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hiebl, M.R.W. Upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research. J Manag Control 24, 223–240 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-013-0183-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-013-0183-1